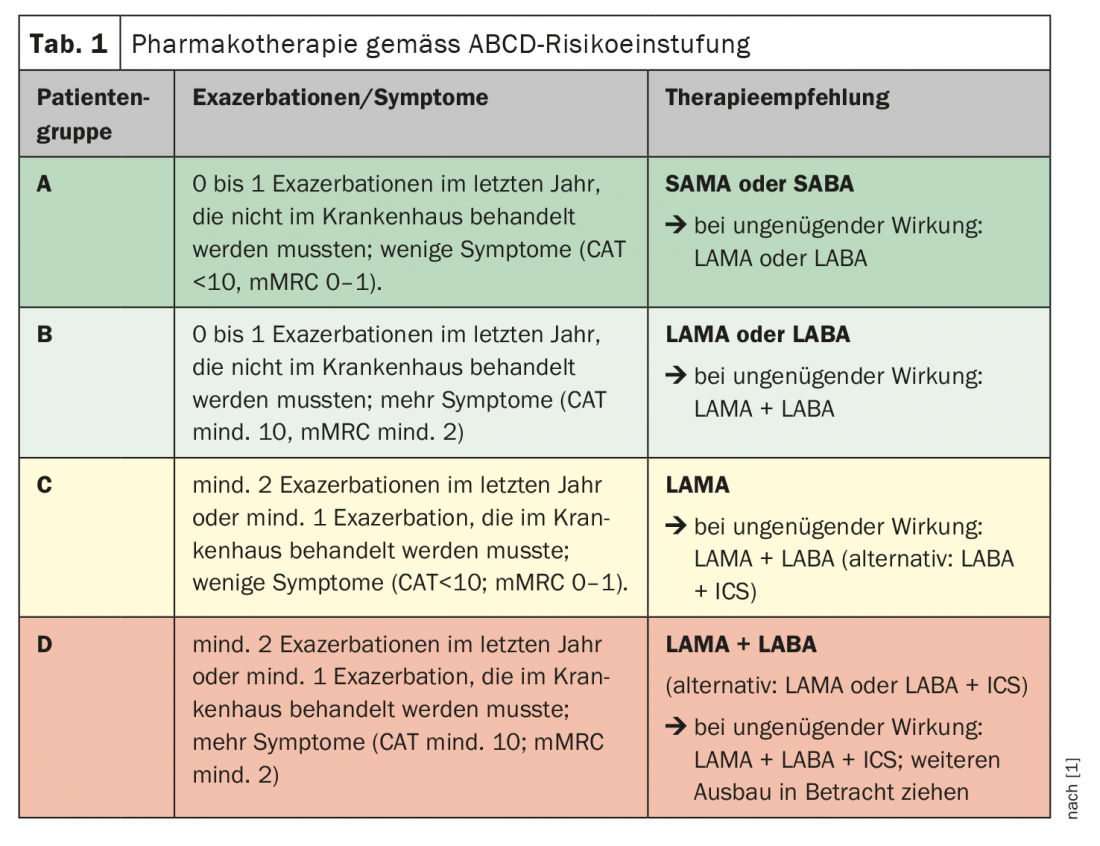

Assessment of symptoms and exacerbation risks is central to effective drug therapy. The ABCD risk classification serves as a basis for this. Here, the indication for therapy is based on respiratory symptoms and the number of exacerbations, regardless of FEV1. If monotherapy is not effective, a two-drug combination or “triple therapy” of LAMA plus LABA combined with an inhaled steroid may be useful, as recent study data confirm.

According to the Swiss Lung League, there are about 400,000 COPD sufferers in this country, and the sequelae are among the leading causes of death [1]. Long-term smoking, along with exposure to other pollutants, is the most important risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Smokers and ex-smokers over 40 years of age with 20 “pack years” and cough have a 50% chance of being diagnosed with COPD [4]. However, about one-third of those affected say they have never smoked. Non-smokers who develop COPD have particularly narrow airway ramifications as shown in a 2020 study published in JAMA [2].

Exacerbation rate and extent of symptoms central for indication

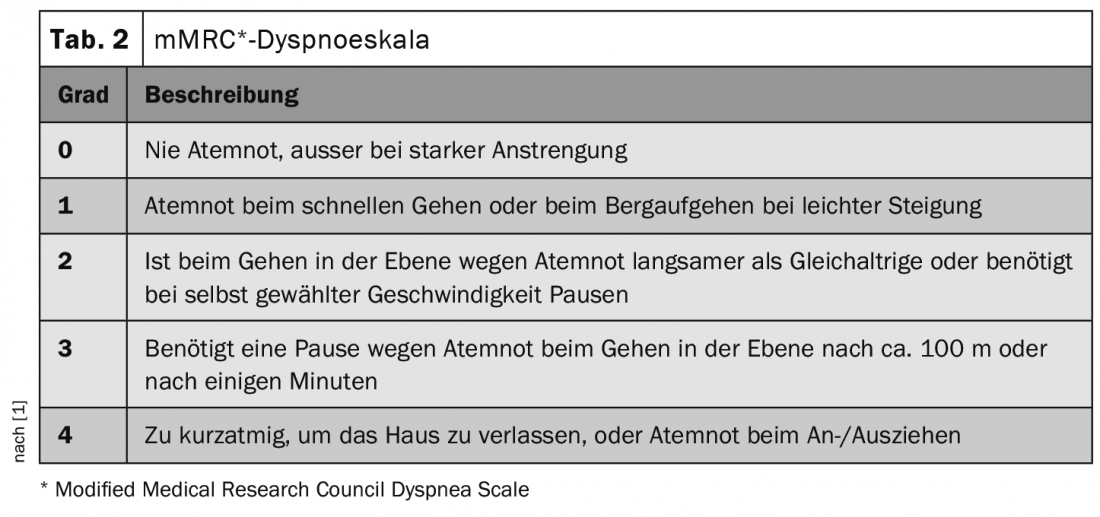

The two characteristic features of COPD are, on the one hand, cough with or without sputum and shortness of breath and, on the other hand, obstruction in parts of the airways. Initially, the cough occurs only during physical exertion, and later also at rest. Since the lung function respectively the FEV1-value (one-second capacity) is not necessarily directly related to quality of life, symptoms, or frequency of exacerbations, since 2017 drug therapy for COPD has been primarily based on ABCD classification (Tab.1). The severity of symptoms can be assessed using either the so-called COPD Assessment Test (CAT score) or the Modified British Medical Research Council Questionnaire (mMRC) (Tab. 2). The basic medications in symptomatic patients with mild or moderate obstruction with and without frequent exacerbations are long-acting anticholinergics (“long-acting muscarinic-receptor antagonist”, LAMA) and long-acting beta agonists (“long acting beta agonist”, LABA). The choice between LABA and LAMA depends on the individual patient’s response. There is evidence that LAMAs are somewhat more effective in preventing exacerbations and LABAs tend to have a stronger symptomatic effect [4].

LAMA/LABA combination drugs as second-line therapy.

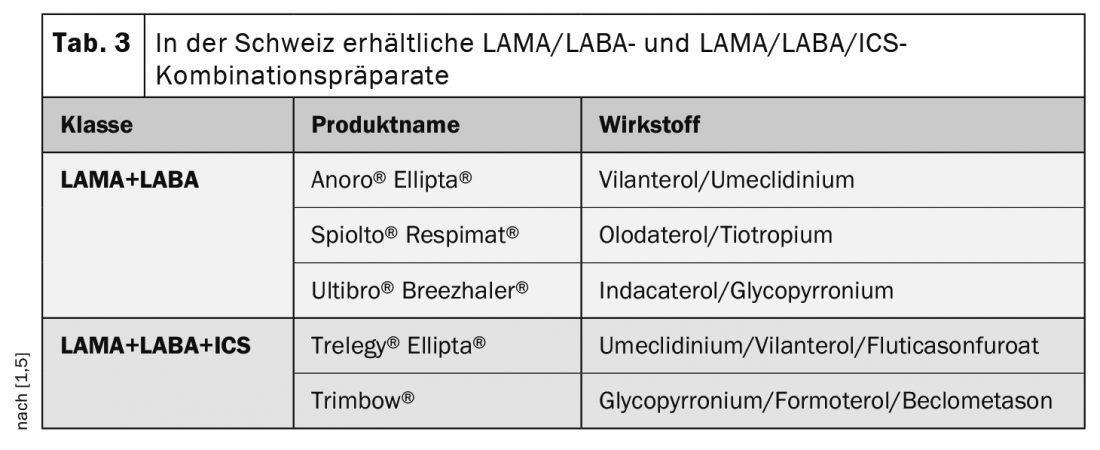

Combination therapy with LAMA+LABA has a moderate add-on effect in terms of lung function and quality of life compared with bronchodilator monotherapy. LAMA/LABA combinations are approved in Switzerland as second-line therapy for patients in whom monotherapy is not effective (Table 3). LAMA/LABA combinations are also superior to ICS/LABA combinations in the prevention of exacerbations and cause significantly fewer pneumonias [4]. For continuous treatment with ICS or an ICS/LABA combination, there is an increasingly weaker evidence base – unlike in bronchial asthma [4]. Tapering and discontinuation of ICS therapy is possible in the majority of COPD patients without affecting exacerbation frequency, especially if they do not have blood eosinophilia [4]. Whereas ICS plus LABA may be the first choice in patients with a history of asthma-COPD overlap or related features, respectively. Anamnestic indications are allergies, asthma, rhinitis in self history or family history and blood eosinophilia.

“Triple therapy” has proven additional benefit

If further exacerbations occur despite treatment with LAMA+LABA or LABA+ICS, treatment with a triple combination (LAMA+LABA+ICS) may be useful to reduce the rate of exacerbations (Table 3). Consultation with pulmonologists is recommended before initiating a triple combination. An important point is the correct inhalation technique, this is crucial for effectiveness. Therefore, practice with the patient and periodic reviews should be performed [4]. If the inhalation technique remains inadequate despite training, the selection of a different application system, the use of an inhalation aid if necessary, and the use of a wet nebulizer should be considered.

That COPD patients can benefit from triple therapy consisting of cortisone spray, LAMA and LABA is shown by the results of the randomized and double-blind phase III study ETHOS (“Efficacy and Safety of Triple Therapy in Obstructive Lung Disease”). The triple combination significantly reduced the number of annual exacerbations compared with dual therapy and was shown to improve quality of life. The 52-week study enrolled 8509 patients with moderate to very severe COPD from 26 different countries. The triple combination tested consisted of the inhaled cortisone preparation budesonide (in two different doses), a LAMA preparation (glycopyrrolate), and the β2-sympathomimetic formoterol (LABA). The two dual therapies tested contained LAMA and LABA (glycopyrrolate and formoterol) and a steroid and LABA (budesonide and formoterol), respectively.

Non-smokers can also develop COPD

A research team led by Benjamin M. Smith, MD, a consultant in the Department of Medicine at Columbia University’s Irving Medical Center in New York City, analyzed data from three studies of smokers and nonsmokers with and without COPD in which the subjects’ so-called “airway to lung ratio” was determined. For this purpose, the width of the bronchial ramifications at 19 anatomical regions is measured in computed tomography images and related to the total volume of the lungs. The smaller this ratio, the narrower the airways [2,3]. All three studies (MESA, CanCOLD, and SPIROMICS) indicated: Nonsmokers who developed COPD had far narrower airway ramifications than those smokers who did not develop COPD despite their high tobacco use.

Literature:

- Lungenliga Schweiz: COPD Pocket Guide. Diagnostics and Management Support for Professionals, www.lungenliga.ch (last accessed 05.02.2021)

- Smith BM, et al: Association of Dysanapsis With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Among Older Adults. JAMA 2020; 323(22): 2268-2280. www.cuimc.columbia.edu/news/undersized-airways-may-explain-why-nonsmokers-get-copd

- Lungenärzte im Netz, www.lungenaerzte-im-netz.de (last accessed Feb. 05, 2021).

- www.medix.ch/wissen/guidelines/lungenkrankheiten/copd (last call 05.02.2021)

- swissmedic: www.swissmedicinfo.ch

Further reading:

- www.lungeninformationsdienst.de/krankheiten/copd/diagnose/index.html

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(2): 20-22