Prolonged or chronic exhaustion is a non-specific symptom and must be clarified both medically and psychiatrically in terms of differential diagnosis. Burnout is a stress-related syndrome that can lead to psychological and somatic secondary disorders. The most commonly expressed symptom of burnout is exhaustion, accompanied by a series of individually variable additional symptoms. After successful treatment of burnout, an increased tendency to fatigue, a reduced ability to work under pressure, and an impaired ability to recover may be present for a longer period of time despite restored functional capacity. Constant “energy monitoring” is helpful for estimating the load capacity. In rehabilitation, short periods of exertion with regular breaks are associated with sustained improvement. Reintegration in the workplace must be carried out in small steps, initially at a low percentage, with an appropriate recovery phase and closely accompanied by therapy, depending on the patient’s ability to cope with stress.

Fatigue is a nonspecific, subjectively experienced general condition that manifests as a symptom, complaint, or disorder and can vary in terms of duration, intensity, and impairment. Basically, exhaustion signals to the organism that a regenerative rest and recovery phase is indicated. Prolonged fatigue may present as a prominent symptom of a definable medical or psychiatric disorder or may present as a chronic syndrome that is difficult to assign etiologically. Therefore, a careful differential diagnosis is primarily indicated.

Several medical diagnoses may be associated with prolonged fatigue. These are, for example, internal disorders (e.g., metabolic syndrome, anemia, vitamin D3 deficiency), neurological disorders (e.g., sleep apnea, head/brain trauma, neuroborreliosis), autoimmune diseases (e.g. Multiple Sclerosis), infections, endocrine disorders (e.g., hypopituitarism, isolated hormone deficiency), oncologic disorders (e.g., craniopharyngeoma, malignancies), or iatrogenically induced sedation by drugs. Similarly, some psychiatric disorders are characterized by marked, prolonged exhaustion. Disorders include, in particular, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and addiction. Burnout syndrome is a special phenomenon.

Burnout

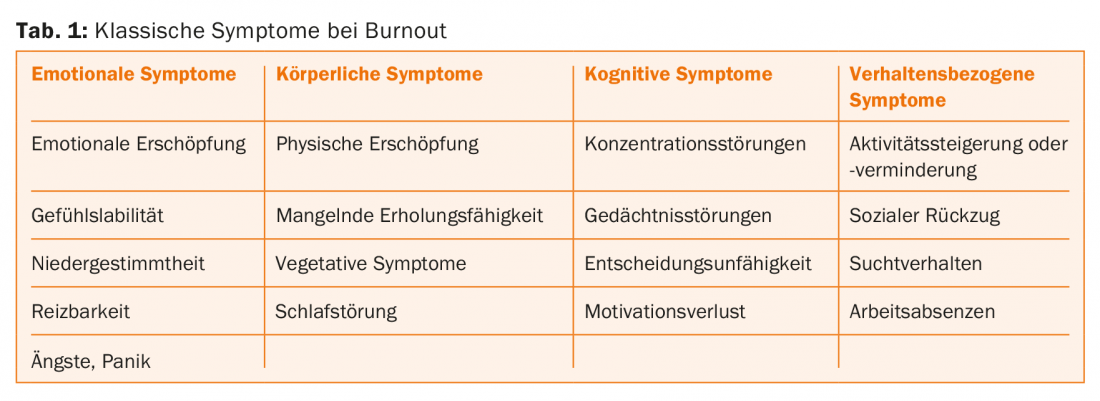

From a medical perspective, burnout corresponds to a stress-associated disorder, whereby the stress load is located in the work context by definition [1]. According to the German Society for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Psychosomatics and Neurology, burnout syndrome represents a risk condition that can lead to psychological and somatic sequelae if the stress load becomes chronic or if recovery is inadequate [2]. Burnout is not considered a stand-alone psychiatric diagnosis, but an accompanying condition. Accordingly, it is classified in ICD-10 as burnout syndrome (Z73.0) [2]. Depending on the severity, high overlaps with depressive disorders and neurasthenia are found, as well as an increased risk of disease in the presence of a depressive predisposition [3–5]. Clinically, burnout syndrome is characterized by a number of individually variable symptoms (tab. 1).

Exhaustion is the most common complaint of burnout, but it is not the only characteristic of this disorder. In the original occupational psychology definition of burnout, the dimensions of emotional exhaustion, demotivation, and the subjective assessment of no longer being able to perform effectively are described as central elements [6]. Although exhaustion in burnout is usually long-lasting, it is not to be judged as chronic. It is quite changeable with adequate therapy and rehabilitation.

On the one hand, stress-inducing factors in the work environment act as risk factors for the development of burnout. These are in particular work overload, lack of autonomy, of appreciation, of team spirit and of justice as well as conflicts of values or uncivilized behavior. On the other hand, personal attitudes and coping strategies are also associated with an increased risk of burnout. These include a lack of self-esteem, high spending tendency, striving for perfection, emotion-oriented or avoidant coping strategies, insecure-ambivalent attachment style, and lack of social support [1]. Burnout can therefore be understood as an expression of a lack of fit between the work environment and the individual employee [7].

Neurobiologically, burnout can be understood as a consequence of a dysregulation of the stress hormone axis caused by chronic stress and a change in neurotrophic factors in certain regions of the central nervous system. Recent studies suggest overactivity or dysregulation in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical system [8,9].

In the presence of depression, a stress-induced region-specific reduction of neurotrophic factors can be observed, leading to an impairment of neuroplastic processes and thus to various structural and functional changes [10].

Burnout treatment

The treatment of burnout is preferably multimodal. We will not go into detail about treatment here, but we refer to the recently published therapy guidelines of the Swiss Expert Network for Burnout [1,11]. Treatment can be provided on an outpatient basis, under partial sick leave, if resilience is still present, albeit reduced, but must be actively managed. A mere time-out is not conducive to achieving the goal. The extent to which the affected person can regenerate in the previous personal and professional environment depends on whether relief from the main stress factors is possible, and whether the social environment is supportive and sustaining. If the patient has lost most of his or her ability to function in everyday life as a result of the burnout, or if distancing from the stress factors cannot be achieved at home , as well as in the case of pronounced psychiatric comorbidity, hospitalization is advisable.

Rehabilitation for burnout

After a successful burnout treatment, the affected person shows a remission of depression, the regaining of concentration ability and memory performance, as well as an understanding of both the individual and the risk factors relevant in the work context. These newfound constructive coping strategies, combined with improved stress management and conscious self-care, contribute significantly to rehabilitation.

In terms of vitality and resilience, burnout sufferers differ considerably even after treatment. Depending on how pronounced the exhaustion was, a prolonged period of increased fatigue tendency, reduced resilience, and limited ability to recover can also be expected. This phenomenon can be called the neurasthenic component of burnout syndrome. In other words, the affected person is intrinsically functional again in all respects, but exhibits increased exhaustibility and a longer recovery period to the extent that he or she is active beyond the extent of his or her resilience.

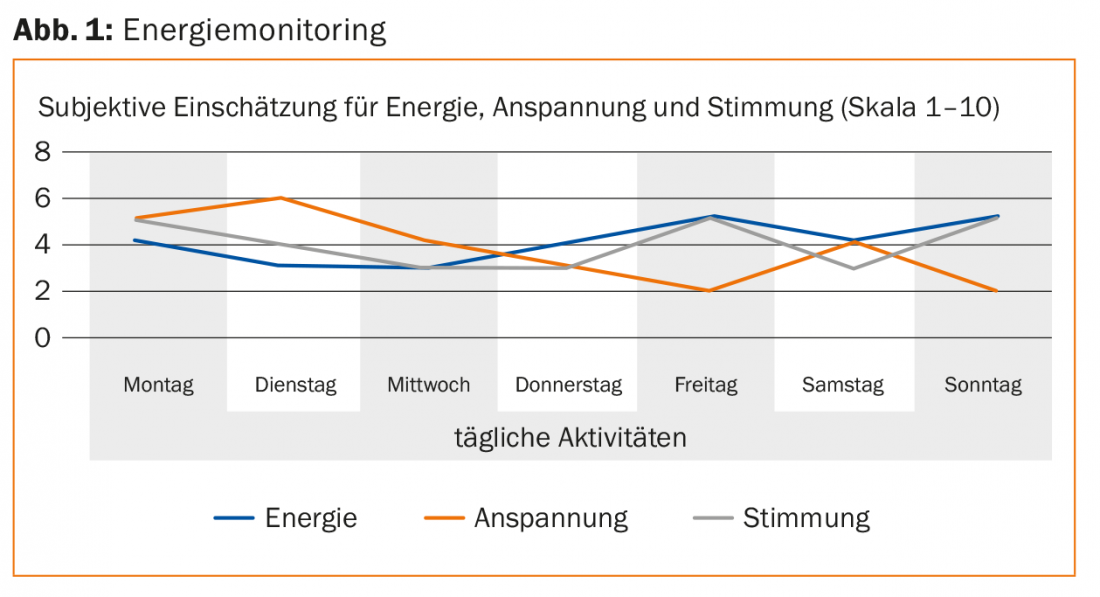

This is where another important part of the rehabilitation process comes in. The affected person must learn which activities and stresses exceed the limits of his or her resilience. So-called energy monitoring is suitable for this purpose (Fig. 1) . The patient is asked to record his or her subjectively perceived energy and tension, incl. the energy level of the patient. of his mood, on a scale of 1-10. In parallel, he should note down the activities and stresses he was dealing with at the time. He, as well as the practitioner, will easily recognize when he has bitten off more than he can chew. It can be observed that when tension is high, the patient tends to feel overwhelmed and subsequently exhausted for longer. Mood usually runs in parallel with energy. The optimal activity is the one that makes the patient feel energetic, in a good mood and relaxed.

In addition to energy monitoring, it is important to ask the patient to take regular breaks. This avoids exceeding the stress limit and gives the organism the chance to relax and regenerate again and again. Energy monitoring is also a good tool for assessing resilience with regard to work reintegration. The more often the affected person avoids overloads and increases their loads depending on the energy monitoring, the faster they will regenerate sustainably.

Reintegration into the work process

Rehabilitation includes, on the one hand, enabling the patient to cope with his daily life again without returning to exhaustion. On the other hand, it must prepare the patient to resume his professional activity. This requires addressing the previous stressors, clarifying how far external stressors in the work environment can be changed, and how the patient themselves can reduce their stress levels by changing their approach. In addition, building constructive resources and addressing personal values, goals, and needs is relevant in psychotherapy. During rehabilitation, it is beneficial to revisit these areas with the patient. Afterwards, a joint discussion should be held with the employer (direct supervisor, human resources service, if necessary case manager of the daily benefits insurance) and the patient. The goal of this conversation is to create a mutually agreeable reintegration strategy. Depending on his resilience, the patient should gradually return to an adapted job, initially with a small workload and with sufficient breaks between the individual work units. Reintegration and rehabilitation may well take several months after a pronounced burnout. Considering such a strategy is the main prerequisite for a sustainable recovery from burnout.

Early return to work makes sense if the above recommendations can be implemented. If reintegration cannot take place at the original workplace – either because the work context does not allow it or because the patient was dismissed or perceives the original workplace as too stressful, usually due to previous conflicts – this can also take place by means of work training at another workplace. Such work training can be supported either by case management or by the disability insurance (IV). The latter variant can take place within the framework of so-called job coaching [12].

Summary

Burnout is a stress disorder that usually manifests itself through prolonged exhaustion. It is a risk condition for subsequent mental and somatic disorders. Burnout is understood as an expression of a lack of fit between the work environment and the individual employee. Risk factors can be located in the work context as well as in the individual. After successful treatment, in many cases there is a prolonged increased tendency to fatigue as well as reduced resilience and ability to recover. By means of energy monitoring, the affected person learns to better assess his or her resilience. By means of activity planning that takes into account resilience and incorporates appropriate breaks, sustainable rehabilitation can succeed. Reintegration into the work context must take place gradually in a suitable environment and in consultation with all parties involved.

Literature:

- Hochstrasser B, et al: Therapy recommendations of the Swiss Expert Network for Burnout – Burnout Treatment Part 1: Fundamentals. Swiss Medical Forum 2016; 16(25): 538-541.

- H. Dilling, et al: WHO – International Classification of Mental Disorders, Chapter V (F), Clinical Diagnostic Guidelines. Bern: Hans Huber, 1993.

- Ahola K, et al: The relationship between job related burnout and depressive disorders – results form the Finnish Health 2000 Study. Journal of Affective Disorders 2005; 88: 55-62.

- Angst J, et al: Depression, burnout or crisis? The different faces of depression in the “Zurich Study”. Cham: Selo Foundation, 2012.

- Nyklicek I, et al: Past and familial depression predict current symptoms of professional burnout. Journal of Affective Disorders 2005; 88: 63-68.

- Maslach C, et al: The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of occupational behaviour 1981; 2: 99-113.

- Maslach C, et al: The truth about burnout. Vienna, New York: Springer, 2001.

- Menke A, et al: Dexamethasone stimulated gene expression in peripheral blood indicates glucocorticoid-receptor hypersensitivity in job-related exhaustion. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014; 44: 35-46.

- Holsboer F, et al: Stress hormone regulation: biological role and translation into therapy. Annu Rev Psychol 2010; 61: 81-109.

- Krishnan V, et al: The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature 2008; 485: 894-902.

- Hochstrasser B, et al: Therapy recommendations of the Swiss Expert Network for Burnout – Burnout Treatment Part 2: Practical Recommendations. Swiss Medical Forum 2016; 16(26/27): 561-566.

- Jäger M, et al: How sustainable is Supported Employment? A catamnestic study. Neuropsychiatry 2013; 27(4): 196-201.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(6): 18-21.