Coronary CT is highly ranked for the work-up algorithm in the updated European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines. Calcification is an important prognostic indicator and has therapeutic implications. Among other things, statins may contribute to a reduction in the risk of MACE depending on the presence of coronary calcium.

In addition to renaming stable coronary artery disease to chronic coronary syndrome (CAD/CCS), there have also been some content changes in the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines published in 2019 [1]. Of practical relevance are mainly the revision of the pre-test probability and the introduction of the clinical probability. These adjustments are intended to increase diagnostic and prognostic accuracy as a basis for the most adequate risk assessment possible and the treatment measures derived from it, explained PD Michael Zellweger, MD, University Hospital Basel, at the FOMF Update Refresher 2020 in Basel [2]. The new term “chronic coronary syndrome” (CCS) reflects the understanding of a progressive course of the disease with the dynamic process of atherosclerosis.

Pretest probability revised

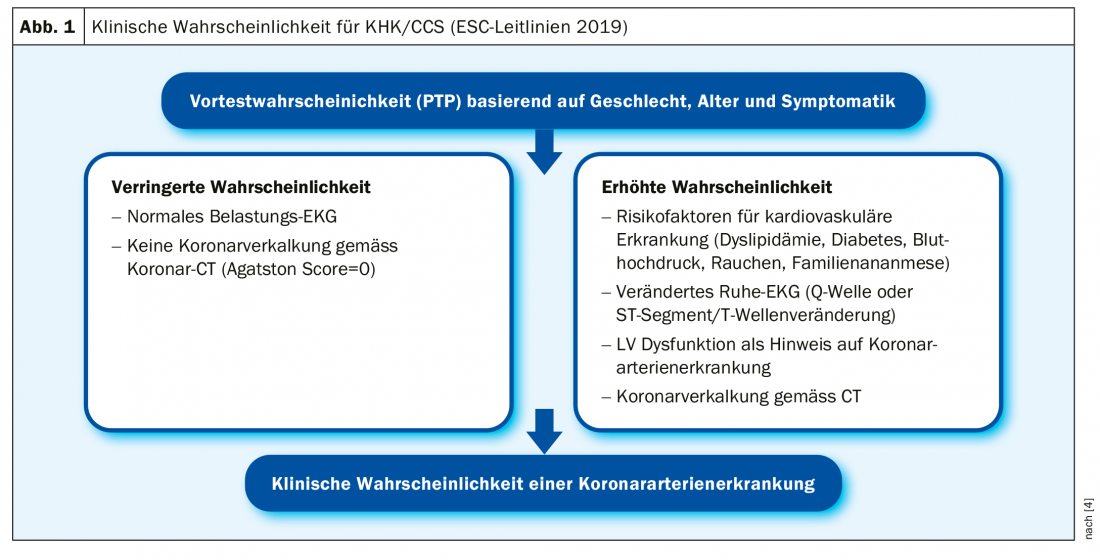

Pretest probability (“PTP”) allows estimation of CHD/CCS likelihood based on age, sex, and symptomatology (typical vs. atypical vs. nonanginal symptoms) [3]. Especially in women, the new guidelines revised the probability criteria for the presence of CHD/CCS downward by about one-third to avoid unnecessary diagnosis. In addition, dyspnea was added as a major clinical symptom in the updated guidelines, as it is a symptom of CHD/CCS that has not been adequately weighted in many patients to date. In summary, PTP allows classification of patients into low (<15%), intermediate, and high risk groups. If the PTP is <15%, further investigations are only necessary if symptoms are unclear. For optimized risk stratification, the inclusion of clinical probability has also recently been proposed. This additional procedure takes into account various factors that increase or decrease the probability of the presence of CHD/CCS (Fig. 1).

Coronary CT for exclusion diagnostics

Noninvasive ischemia imaging or coronary CT is recommended as the first test in symptomatic patients if CHD/CCS cannot be excluded by clinical assessment. “The strength of coronary CT is its high negative predictive value,” the speaker explained [2]. That the presence of CHD/CCS can be excluded with a very high probability in the presence of normal findings on noninvasive coronary CT examination is empirically supported [5]. The speaker illustrated this with a CT image showing normal coronary vessels that are plaque and calcium free. calcification has a very good prognostic significance. If no coronary calcification is detectable, a very good long-term prognosis can be made. This is shown by longitudinal data with a follow-up period of 15 years (n=9715), according to which the mortality rate of patients without coronary calcification was 3% compared with 28% in those with a coronary calcification score >1000 at baseline [6]. In a 50- to 60-year-old patient with a CAC (coronary artery calcification) score of 0, a 15-year “guarantee period” can be assumed. In terms of repeat risk stratification, this means that without a drastic change in symptoms, retesting is moot. Using various example findings from coronary CT examinations, the speaker will illustrate the diagnostic criteria and their implications for the further clarification procedure:

Example finding 1: Non-stenosing CHD/CCS (CAC score >0, or “soft plaque,” <50% stenosis). In addition to addressing lifestyle factors, the question arises whether drug prophylaxis by means of statins or aspirin is useful.

Example finding 2: Stenosing CHD/CCS (CAC score >0, or “soft plaque,” 50-75% stenosis). The question here is whether hemodynamically relevant or not. For this purpose, a functional test is indicated, for example, stress MRI or PET-CT. If hemodynamically relevant coronary artery disease can be ruled out, lifestyle measures should be addressed, as well as possibly prophylactic drug treatment with aspirin or statins. If the findings of the follow-up examination reveal hemodynamically relevant coronary artery disease, which causes large ischemia under stress and is highly prognostically relevant, the patient should be revascularized.

Example finding 3: If coronary CT reveals high-grade stenoses, direct invasive coronary angiography is useful as a basis for adequate treatment.

In conclusion, invasive intervention by cardiac catheterization is recommended only for patients at high risk for severe symptoms (pretest probability >85%), but not for intermediate coronary stenosis without ischemia [4].

Statins effective in coronary calcification

A longitudinal study (n=13 644) was able to show that the benefit of prophylactic statin therapy can be made dependent on the degree of calcification. With a CAC score of >101, statin therapy was statistically significantly less likely to result in MACE (major adverse cardiac events) compared with patients without statin treatment (p<0.0001, NNT=12) [7]. In contrast, no difference was measurable with a CAC score of 0. Whether and under what conditions aspirin is useful as primary prevention is controversial. There are some large studies from which it appears that aspirin is not recommended as primary prevention. The speaker put it into perspective, “Yes according to CAC score, aspirin therapy should definitely be discussed,” There are empirical data showing that prophylactic aspirin treatment can be effective in high CAC score [8]. The analysis based on the MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) trial with data from 4229 patients demonstrated that individuals with a CAC score ≥100 benefit from aspirin as primary prophylaxis.

Conclusion

“When coronary artery disease is excluded, CT is gaining importance in the new guidelines. It is mainly used in the area with low pretest probability, if clarification is necessary at all,” summarizes Dr. Zellweger [2]. Functional testing should be used when pretest probability and clinical probability are higher. Revascularized patients always receive a functional test; CT is inappropriate for this patient group [2,4].

Source: FOMF Basel

Literature:

- European Society of Cardiology (ESC): www.escardio.org

- Zellweger M: Coronary artery disease – evaluation and diagnosis. Slide presentation, PD Michael Zellweger, MD, FOMF Update Refresher, Basel, Jan. 31, 2020.

- Montalescot G, et al. (Task Force): 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2013; 34 (38): 2949-3003

- Knuuti J, et al: 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes: The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2019; ehz425.

- Marwick TH, et al: Finding the Gatekeeper to the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory: Coronary CT Angiography or Stress Testing? J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65(25): 2747-2456.

- Shaw LJ, et al: Long-Term Prognosis After Coronary Artery Calcification Testing in Asymptomatic Patients: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med 2015]. Ann Intern Med 2015;163(1): 14-21.

- Mitchell JD, Fergestrom N, Gage BF, et al: Impact of statins on cardiovascular outcomes following coro-

- nary artery calcium scoring. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72: 3233-3242.

- Miedema MD, et al: Use of coronary artery calcium testing to guide aspirin utilization for primary prevention: estimates from the multi-ethnic study of athero-sclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014; 7(3): 453-460.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2020; 15(6): 36-37 (published 6/16/20, ahead of print).