This heterogeneous multisystem disease with immune-mediated pathomechanism has skin involvement in 20-30% of cases, and other organs are affected in 60%. In addition to histological examination, a differential blood count is required for diagnosis. The spectrum of therapeutic options ranges from topical glucocorticoids or calcineurin antagonists to hydroxychloroquine and biologics.

By definition, inflammation is granulomatous if the infiltrate consists of at least 50% histiocytes/macrophages [1]. The pathomechanism is immune-mediated. It is a reaction pattern that develops when immunogenic noxae from the outside world cannot be eliminated by the immune system, explains Prof. Dr. med. Matthias Goebeler, University Hospital Würzburg [1]. “There is activation of T lymphocytes with release of cytokines, such as TNF, IL12, IL18, and chemokines, which induce a granulomatous inflammatory response,” the speaker specified. A distinction is made between infectious and non-infectious granulomatous diseases. Sarcoidosis is classified as the latter. The etiology is unclear; a combination of genetic determinants and extrinsic trigger factors is thought to be involved. This thesis is supported by twin studies. The annual incidence rate in the general population is approximately 1-4:10,000, and sarcoidosis is most common in the 30-40 year age group.

Chameleon among skin diseases

Clinical manifestations can sometimes vary widely. Cutaneous symptoms are present in 20-30% of cases and skin involvement is the first symptom in one-third of patients. In 60%, other organs are affected [1,2]. The most common form is small-node disseminated sarcoidosis. These are papules up to 5 mm in size that appear isolated or grouped. Predilection sites include the face and extensor sides of the extremities. In 80% of cases, spontaneous healing occurs within two years. This is not true of nodular sarcoidosis, which is characterized by livid red, coarse nodules; organ involvement is very common in this subtype of sarcoidosis. In the plaque form of sarcoidosis, chronic courses of the disease are more typical; 90% of those affected do not heal within 2 years. Predilection sites are face, buttocks, back, extrathoracic involvement is common. An even more severe form of sarcoidosis is lupus pernio. Often there is a chronic-progressive course of the disease. Symptoms are usually localized to the nose, cheeks, buttocks, or hips, and severe pulmonary and extrathoracic organ involvement may occur. A rarer form of sarcoidosis is angiolupoid. These are teleangiectatic lesions on the nose. Sarcoidosis can be caused by tattooing, scars and piercing. Sarcoidosis induced by tattooing should be differentiated from “Tattoo Granulomas with Uveitis” (TAGU). “Sarcoid-like reactions” can also occur as a side effect of certain drugs, such as during therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ipilimumab, novolumab, pembrolizumab, etc.) or as a consequence of BRAF/MEK inhibition.

Interdisciplinary multimodal management

What must not be missed is a histologic examination: a classic finding of sarcoidosis is characterized by epithelioid cell granulomas surrounded by a sparse lymphocytic infiltrate. Basic diagnostics also include a differential blood count, including liver and kidney values. Calcium should be determined in serum and collected urine. In addition, measurement of the following parameters is recommended: ACE, possibly sIL-2R neopterin, ANA (elevated in 30% of cases). Further diagnosis-relevant investigations: low-dose CT thorax, pulmonary function, (long-term) ECG, echocardiography. With regard to consultation examinations, an ophthalmological clarification is always to be carried out, as well as neurological and cardiological examinations if necessary, respectively depending on the symptom characteristics of the respective case.

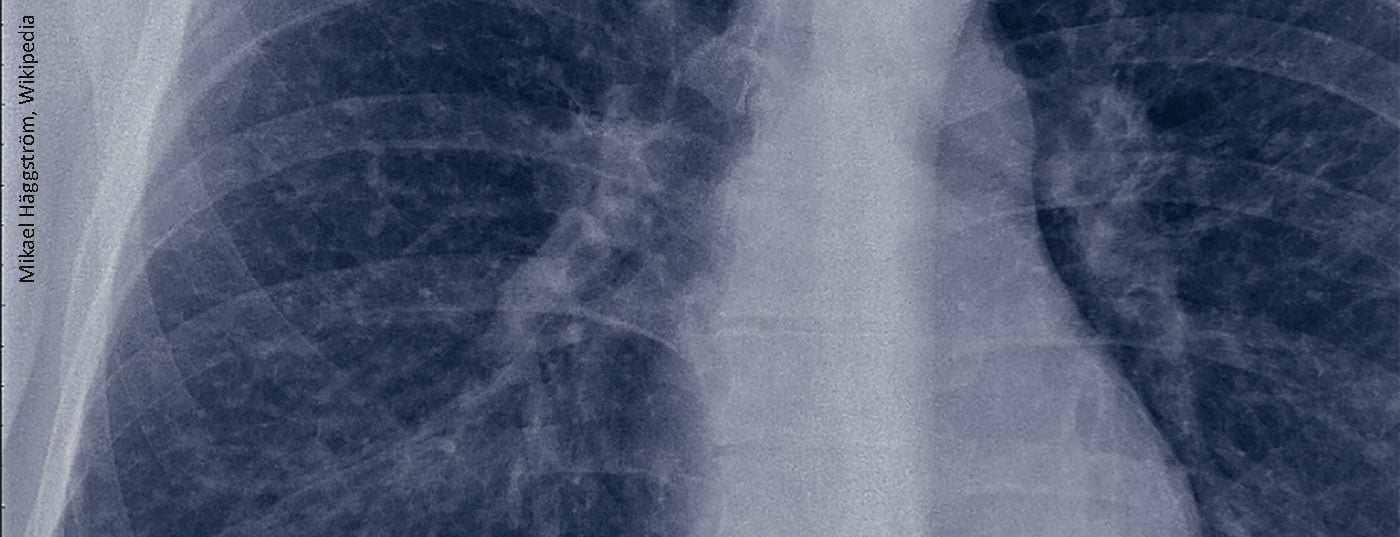

The most commonly affected organ is the lung, which may present with persistent cough and dyspnea, and in severe cases fibrosis may develop. However, the eyes, liver, spleen, heart, nervous system and musculoskeletal system can also be affected.

There are rather few large therapeutic studies on sarcoidosis, and the empirical data are limited to smaller case series and clinical experience. Oral glucocorticoids (prednisone/prednisolone) are recommended as a primary systemic therapy option, depending on response over a period of 6-12 months [3]. In case of nonresponse or intolerance, methotrexate, azathioprine, leflunomide, and mycophenolate mofetil may be used. Methotrexate is most commonly used and is relatively safe in the appropriate setting and with adequate monitoring [4–6]. Good therapeutic results have also been achieved with azathioprine, although the risks of side effects are a critical factor [7]. Leflunomide may be used instead of methotrexate or in combination [8,9]. If antimetabolites are not tolerated or there is no response, a TNFα inhibitor may be considered (e.g., infliximab, adalimumab) [3]. As additional treatment options, rituximab has been shown to be effective in small case series [10,11]. Hydroxychloroquine is a proven therapeutic option, particularly for cutaneous sarcoidosis [12,13].

Source: DERMATOLOGIE KOMPAKT & PRAXISNAH Dresden (D)

Literature:

- Goebeler M: Granulomatous diseases. Prof. Dr. Matthias Goebeler, Dermatology compact & practical, Dresden, 07.02.2020.

- Giner T, et al: [Sarcoidosis : Dermatological view of a rare multisystem disease]. [Article in German]. Dermatologist 2017; 68(7): 526-535.

- Baugham RP, Grutters JC: New treatment strategies for pulmonary sarcoidosis: antimetabolites, biological drugs, and other treatment approaches. Lancet Respir Med 2015; 3: 813-822.

- Baughman RP, et al: Methotrexate is steroid sparing in acute sarcoidosis: results of a double blind, randomized trial. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diff use Lung Dis. 2000; 17: 60-66.

- Lower EE, Baughman RP: Prolonged use of methotrexate for sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155: 846-851.

- Vorselaars AD, et al: Methotrexate vs azathioprine in second-line therapy of sarcoidosis. Chest 2013; 144: 805-812.

- Muller-Quernheim J, et al. Treatment of chronic sarcoidosis with an azathiopri-ne/prednisolone regimen.

- Eur Respir J 1999; 14: 1117-1122.

- Baughman RP, Lower EE: Leflunomide for chronic sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diff use Lung Dis 2004; 21: 43-48.

- Sahoo DH, et al: Effectiveness and safety of leflunomide for pulmonary and extrapulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J 2011; 38: 1145-1150.

- Lower EE, el al: Rituximab for refractory granulomatous eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol 2012; 6: 1613-1618.

- Sweiss NJ, et al: Rituximab in the treatment of refractory pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 1525-1528.

- Korstena P, et al. Nonsteroidal therapy of sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2013; 19(5): 516-523.

- Coker KC: Management strategies for pulmonary sarcoidosis. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2009; 5: 575-584.

Further reading:

- Graf L, Geiser T: The chameleon among systemic diseases: Sarcoidosis. Swiss Med Forum 2018; 18(35): 695-701.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2020, 30(4): 35 (published 8/24/20, ahead of print).