At the 96th Annual Meeting of the SGDV in Basel, a workshop dealt with the broad topic of patient satisfaction: What conditions must be met for the patient to leave the practice satisfied? How is the patient in aesthetic dermatology different from other patients? What is the importance of communication and how should one react in case of objective treatment errors? Various experts discussed possible solutions.

(ag) After a welcome by the workshop organizer and president of the SGEDS Oliver Ph. Kreyden, MD, Muttenz, Switzerland, Patrizia Carrozza, MD, , Bellinzona, Italy, presented the consensus paper. This is about the satisfied patient in aesthetic dermatology (specifically botulinum toxin A treatment). “The consensus work aims to identify ways before, during, and after treatment to increase the percentage of satisfied patients in the practice,” Dr. Carrozza introduced her presentation.

“Until now, patient satisfaction has not been mentioned in the literature, or only in passing. However, it is very important, because what good is a perfect treatment result if the patient does not recognize this or cannot or will not recognize it? That’s why SGEDS explored the question at a two-day consensus conference and will now publish the paper.”

According to one definition, the patient is more satisfied the more he is positively surprised with regard to his expectations or the perceived services turn out better than anticipated. It must be taken into account that the demands and expectations in aesthetic dermatology are particularly high, since, strictly speaking, we are not dealing with patients, but with healthy self-pay patients (from the upper economic strata of society). It is therefore all the more important to create a balance in the balance of power between doctor and patient by contrasting the pure principle of demand with a principle of assistance or by consistently making the “customer” a “patient”. This includes first and foremost a correct diagnosis.

What are the requirements?

Conditio sine non qua for satisfactory treatment: the physician must be able to carry out the therapy in accordance with his or her own judgments, abilities and possibilities. This requires first of all a high level of professional competence, but also social competence (communication, empathy). In addition, the physician must also be skilled in leadership and be able to manage a high-quality team and a professionally organized practice. Last but not least, he must have a certain amount of experience that allows him, for example, to recognize complications quickly and treat them adequately. The goal is recommendation – the highest expression of a satisfied patient.

Main messages of the paper

Several conclusions emerged from the consensus conference, which will now be briefly summarized. Conceptually, the paper breaks down into different stages of treatment: what to consider before the patient’s first visit? What should you pay special attention to during the initial consultation and during the actual treatment? Follow-up care as well as the control appointment were also key topics.

The first telephone contact with the practice and, of course, before that, the serious advertising are crucial. During the interview, the doctor or practice staff must appear empathetic, professional and friendly. Information should be recorded and forwarded correctly, and an appointment should be possible in a timely and appropriate manner.

The initial consultation serves to establish a basis of trust between doctor and patient. It also includes an expert medical assessment and the presentation of a treatment plan based on the patient’s wishes (diagnosis, treatment options, side effects and possible complications). The financial aspect must be clarified and a consent must be signed. In any case, valuable for the diagnosis, but especially also for the follow-up are tools such as video, mirrors, photos (standardized photo documentation is always part of it).

“The actual therapy must proceed competently: Competence means safe, fast, pleasant and professional treatment delivery,” Dr. Carrozza explained.

What does aftercare look like?

In any case, the patient must have received all relevant information about his therapy beforehand, both in writing and verbally. The measures to be taken in the event of side effects and complications must also be clarified. “An emergency number is useful despite this advice and, with accurate education before therapy, is used less often than thought,” she said.

At the follow-up appointment, the results are honestly discussed with the patient and any corrections are taken over without subsequent costs. The quality of the treatment is successfully concluded in this phase by once again conveying competence and making the development clear to the patient step by step, e.g. with photo documentation (learning curve).

The dissatisfied patient

“But how should one deal with dissatisfied patients? First of all, it should be noted that patients are usually more concerned than dissatisfied. Consequently, it often already helps to care for the patient empathetically and, above all, to convince him or her of the correctness of the treatment (before/after pictures). Of course, this only applies to subjective dissatisfaction (doctor satisfied, patient dissatisfied). In the case of objective dissatisfaction (doctor also dissatisfied), a new clarification discussion should be held and improvements made promptly or during the same consultation,” says the expert. Especially crucial in such situations are empathy, listening, perceiving, asking questions and open dialogue. The next presentation dealt with this in more detail.

Communication as a supporting pillar in the therapy concept

“What is always forgotten: The conversation is the most frequent medical and nursing action and decides decisively on the well-being of the patients and companions. Nevertheless, the competence to communicate in medicine is trained far too little. If it fails, the patient leaves the practice dissatisfied, even if the news is positive from a professional point of view,” warned Prof. Matthias Volkenandt, MD, Munich. “If it succeeds, this can take much of the sting out of bad news (e.g., an unsatisfactory aesthetic treatment result) and reconcile the patient, if not with the result, then with you as a person. This is crucial: we doctors are by no means able to guarantee perfection in our decisions, diagnoses and therapies. What we can and should promise, however, are the traditional virtues of a doctor: I want to help to the best of my knowledge and belief (and without monetary ulterior motives), and I am constantly educating myself and my skills. If we succeed in communicating this to the patient credibly and honestly, we create a relationship that goes beyond purely professional care and helps the patient even in difficult situations – in short, he is more satisfied with me as a doctor.”

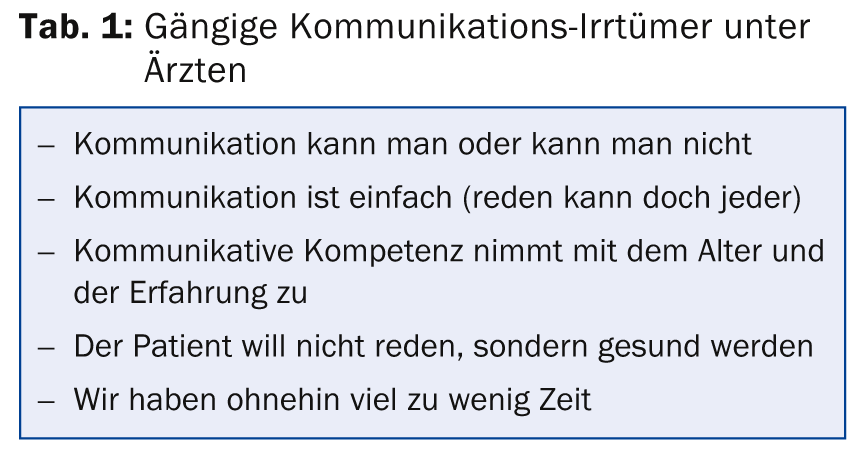

Various misconceptions (Table 1) lead physicians to attach too little importance to communication. It is not uncommon for particularly difficult conversations to be avoided altogether.

Consider content and relationship level

One must learn to differentiate between the professional (content) and emotional (relationship) levels, both as a speaker and as a listener. Optimally, the patient leaves the interview satisfied on both levels (“I received all the information, but I was also listened to and taken seriously”). However, this is only successful if the physician recognizes which level is addressed by a statement. For example, if the patient says, “I am so afraid of the treatment” (e.g., a chemical peel), the doctor can immediately respond with a professional answer (reassurance, advice, information about the therapy, then change the subject). However, the premature professional response – especially if it interrupts the patient – is a kind of distancing and makes it impossible to address the deeper problem. As a result, the patient feels misunderstood and stress increases.

“In the above case, the patient may not have primarily wanted to receive advice – which is not infrequently taken as a beating in the literal sense, signaling superiority rather than community. He was possibly rather in search of empathy and appreciation. The physician must first learn to remain silent or to encourage the patient to continue talking by gently asking questions (active listening). According to this, regardless of the level of training or one’s own views should be an empathic response can be made, as, for example, ‘I understand what you mean’ or by means of rhetorical questions that provoke a positive response, such as ‘So you are afraid of the treatment? By letting the patient tell you, you find out where the real problem lies and can then still – and only secondarily – address it with a professional response,” says Prof. Volkenandt. It could turn out, for example, that the above-mentioned statement rather involves the following fear: “What are we going to do if the therapy does not lead to the desired aesthetic result, perhaps even disfigures me? Will I have a cat-eyed and frozen face like some Hollywood actors afterwards?”

But how are you supposed to invalidate and mitigate this fear if you, as a communication partner, are not even aware that it exists? That’s why accurate empathic listening is also so important to patient satisfaction, he said: “The patient is not open to technical information until empathy has first been signaled.”

Successful workshop – satisfied audience

The reactions of the audience showed that the training event also did everything right in terms of communication. The workshop met with visible and audible interest among the numerous participants: Prof. Volkenandt’s humorous reenactment exercises were received with great pleasure and engaged discussions arose with the speakers.

Source: SGEDS workshop at the 96th Annual Meeting of the SGDV, September 4-6, 2014, Basel, Switzerland.