Multimodal treatment of children with ADHD works best when physicians and therapists work well with the “family” and “school” systems. This can be accomplished if recommendations for multimodal treatment and especially school-based interventions are considered. Further improvement in treatment in the future will also depend on whether school policy decisions take into account the needs of children with ADHD by providing more specific services (small classes, sufficient staff, adaptation of curricula and school types) and training for teachers.

Epidemiological studies consistently find evidence that ADHD has among the highest prevalence for disorders in childhood and adolescence [1]. Also in pediatric and child and adolescent psychiatric practice, simple activity and attention disorder (ICD-10 F90.0), also called attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), is among the most common reasons for presentation for diagnosis and treatment of children and adolescents with psychological, school, and social problems [2].

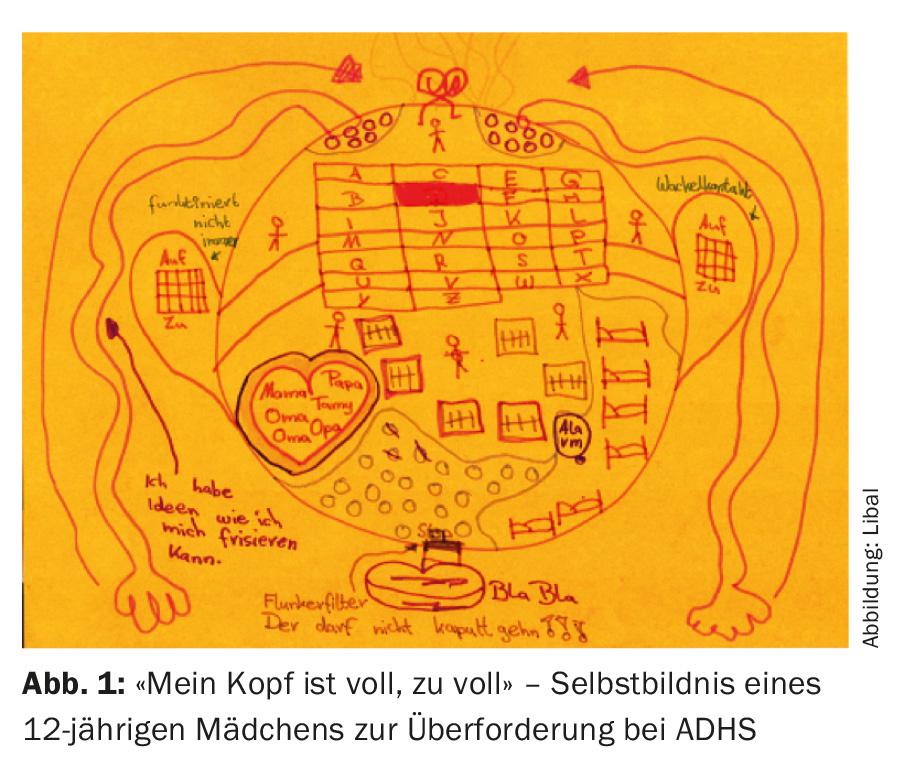

It will come as little surprise that schools come into focus here. Entering school is a critical hurdle for children with ADHD, and it can get bigger with each school year. The requirement to sit still and control behavior themselves challenges and sometimes overtaxes the young ADHD patients (Fig. 1) . They cannot wait sufficiently well or maintain their concentration for more than 45 minutes. They do not yet succeed in realizing their intellectual potential, and they quickly become disappointed and frustrated. Children with ADHD want to be integrated into the school class, want to have successes, and want to play with friends during recess.

School problems are common

For these reasons, a presentation for clarification of the issue of ADHD usually occurs during the first years of school, often soon after the start of first grade. Compared to kindergarten, school not only makes greater demands in the areas of concentration and attention, but also requires a general behavioral adjustment to the structured situation in the classroom. This adjustment is much more difficult for children with ADHD, which is why they are more likely to display disruptive behavior in class and show corresponding learning and performance problems. As a further consequence, children perform increasingly poorly at school, which cannot be explained by their cognitive abilities, and which may ultimately lead to secondary disorders of emotional development (anxiety, depression) and social development (social behavior disorder) [3]. Of course, this development can also occur in children without ADHD, for example if they are enrolled in school too early, if they are not trained according to their cognitive ability and are thus permanently overtaxed, or if children are exposed to (emotional or social) stress in the family.

Social integration into the school environment, and especially into the classroom, can also be a difficult task for some children. Difficulties in social integration can affect socially anxious children who are unhappy about not finding a connection, but also children who are actively excluded (bullying) or exclude themselves, e.g. due to autistic symptomatology.

This also partially answers the question of why more children in a class are often classified as conspicuous and recommended for ADHD assessment than would be expected based on the results of epidemiological studies. In large meta-analyses of epidemiological studies on the (worldwide) prevalence of ADHD, data are found in the range of 3.4-7.2% [1,4,5]. There are no statistically significant differences between North America and Europe, with only the United Kingdom having comparatively lower prevalence rates of childhood ADHD [4]. Taking this information as a basis, one would assume that one to two children in each class suffer from ADHD.

Diagnostics, comorbidity and differential diagnosis

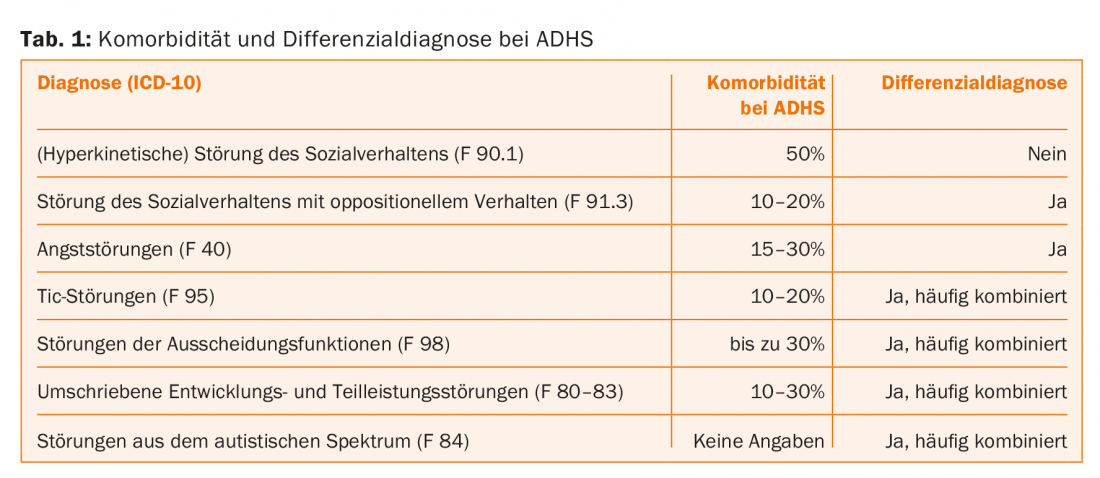

When evaluating children with suspected ADHD, the challenge is to determine whether the school difficulties and behavior problems have developed because of ADHD or because of other psychological and social problems. ADHD often occurs with one or even more comorbid disorders. For example, approximately 70-90% of children with ADHD have a comorbid disorder that also needs to be diagnosed. Most often (in more than 50% of cases), a disorder of social behavior can also be diagnosed, which is classified as hyperkinetic disorder of social behavior (F90.1). Also common are anxiety and depressive disorders, as well as tic and excretory dysfunction. Developmental (language and motor) and (isolated or combined) partial performance disorders (dyslexia, dyscalculia) are also frequently seen in children with ADHD or must be clarified as a differential diagnosis, as they can also cause school problems and behavioral disorders (Tab. 1) [3].

The guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD (e.g., of the DGKJP) unanimously recommend a detailed case history (current symptoms and history), an examination of the child, and the use of self/other assessment questionnaires and test psychological procedures [6]. If not already presented as an urgent problem by the parents, the school situation (class size, teaching methods, seating arrangements), the homework situation (location, duration, support), but also the remaining time for leisure activities and sleep (falling asleep, quality and duration) should be addressed in the case history survey.

The peer evaluation forms should also be completed by classroom teachers, if possible. A teacher’s description of strengths, weaknesses, and classroom behavior in writing or by contacting the school directly is also helpful.

A check of cognitive performance (e.g., with the Wechsler Intelligence Test for Children, WISC) can not only reveal possible overachievement at school (for example, due to an unsuitable school form or an unsuitable individual approach), but also provide helpful information for securing the diagnosis and also for further counseling by interpreting the performance at the individual test level. It should be reiterated that comorbid disorders are the rule rather than the exception in ADHD. Problems with social behavior or wetting are usually reported spontaneously, whereas anxiety, tics, problems with reading, spelling or arithmetic, and depressive development often need to be specifically asked about [7].

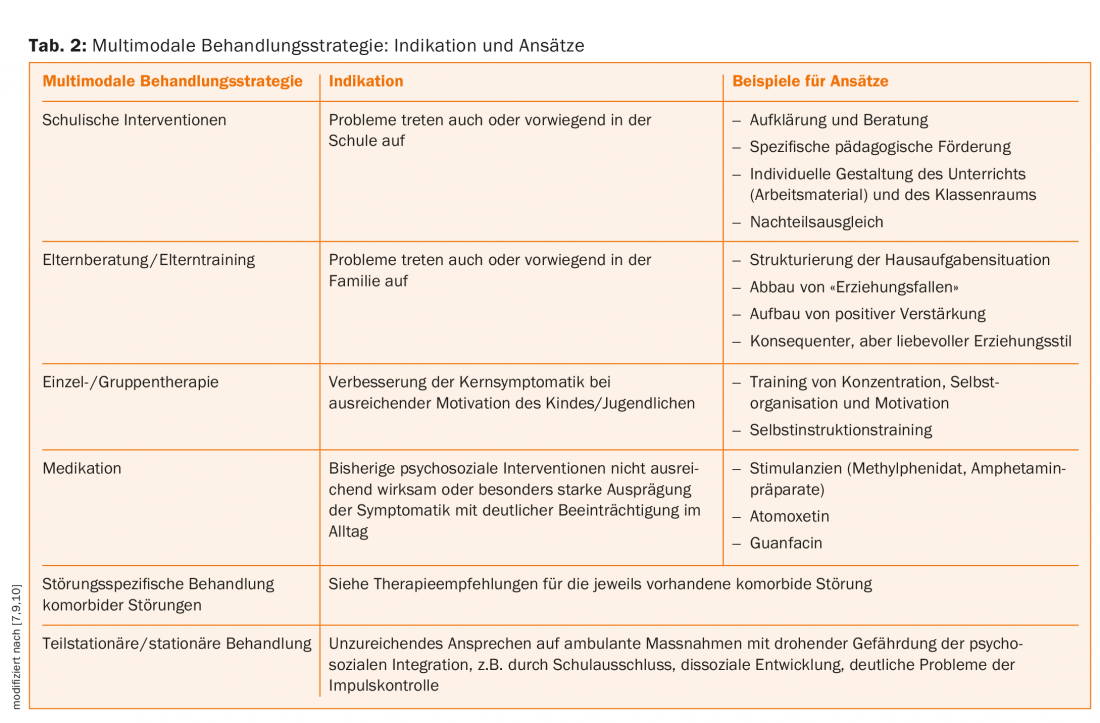

Treatment of ADHD should have a multimodal approach, if possible [6,8]. In addition to drug therapy and systemic approaches (parent training, school-based interventions), for which good evidence of efficacy can be found, there is also a plethora of non-drug therapies whose efficacy is not yet well established [6,8,9]. An overview of the various treatment modalities is provided in Table 2. The following discussion focuses primarily on school-based intervention options.

School interventions – general and specific recommendations

Children and adolescents with ADHD should be able to experience in the school context that they are not stupid, forgetful and bad, but that they are supported by all those involved in the system to learn strategies to deal successfully with their attention and impulse control disorder. These children need acceptance, understanding, boundaries and structure, and especially a sense of achievement.

For this to succeed, children depend on a consistent orientation in the family and school context. The “control center” of any therapeutic concept within the multimodal approach should be with the physician who provides long-term care for the child. Transparent and continuous cooperation with parents and teachers is an essential building block for the success of the therapy, especially when it comes to pronounced hyperkinetic and/or oppositional behavioral problems. The more comprehensive the teachers are informed about the treatment plan and the medication, and the more trusting the communication and cooperation with parents and teachers, the more successful the supportive measures can be.

Briefly summarized, the following points can relieve teachers and lead to good cooperation with parents [10]:

- Education and counseling: The basis of any intervention should be comprehensive education and counseling. The more intensively all those involved plan and implement the supporting measures together as a team, the greater the likelihood of achieving sustainable changes in behavior.

- Increasing skills: Overriding goals in educational support in the school context are to increase the abilities to perceive oneself and others and to control oneself, to increase self-efficacy, social skills, the ability to deal with stress, and problem-solving skills.

- Achievable goals: The more often these children are criticized for their “misbehavior,” the more likely they are to become defensive, to which their counterpart then reacts again with anger. This can result in a complete refusal to perform. In order to break this negative spiral for children with ADHD in the school context, it is important to always first realistically assess the children’s abilities and resources when agreeing on goals and to set achievable goals. Children’s efforts should be at the forefront of all interventions.

- Recognition and appreciation: All children can learn to accept each other and to treat each other appropriately and supportively. This requires transparency and knowledge of the background and a willingness to recognize and appreciate. Therefore, professionals should support teachers in providing informational services for the school community, as well as child-centered services for the affected classes.

- Reducing disruptive potential: Children with ADHD make special demands on their teachers and classmates, but they do not need a special role. The more their strengths are emphasized and the more friendly, relaxed, calm, but also directive, consistent and assessable the adults learn to deal with these children, the more sustainably positive the relationship level becomes and the potential for disturbing behavior can be reduced.

- Structure: The lessons, classroom and work materials for children with ADHD should be structured to a special degree. The seat should be at the very front or in a corner, not next to a window or an open bookcase. Frequent changes of place should be avoided. It is helpful if teachers maintain a lot of eye contact, face the child head on, and make sure to address the child in a personal, direct manner. This gives the child the feeling that he or she is being noticed. Children with ADHD usually perceive very sensitively whether they are liked and whether their counterpart is a match for them, so they must authentically feel that the teacher is not indifferent to them with their peculiarities, but is accepted. Supportive are the pointing out of possible solutions instead of blaming and non-verbal impulses.

- Praise positive behavior: writing exercises should be reduced and alternative ways of learning should be expanded. The handwriting of children with ADHD should never be compared to the handwriting of normative children and should be evaluated with grade deduction. Punitive work is absolutely counterproductive and only leads to an increase in stigmatization (it embarrasses children). It is important that adults sharpen their focus on what children are doing well, praise efforts and positive behavior directly in an appreciative manner, and ask solution-oriented questions instead of making accusations.

- Physical Education: In physical education classes, care should be taken to provide meaningful motor assignments. The more only frolicking is allowed, the more a child with ADHD circles, increasing his or her arousal level. The choice of activities should always take into account the limited perception of dangerous situations and possible motor clumsiness.

- Homework: Children with ADHD need special assistance in taking notes on homework and always a “check” on homework the next day as appreciation and recognition for their efforts.

- Compensation for disadvantages: The possibility of individual compensation for disadvantages should be discussed and determined in cooperation with parents, teachers and the school administration.

Literature:

- Polanczyk G, et al: Annual Research Review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in Children and Adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2015 Mar; 56(3): 345-365.

- Döpfner M, et al: Mental abnormalities of children and adolescents in Germany – results of a representative study: methodology, age, gender and judgement effects. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiater Psychother 1997.

- Taurines R, et al: Developmental comorbidity in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2010; 2: 267-289.

- Polanczyk G, et al: The Worldwide Prevalence of ADHD: A Systematic Review and Metaregression Analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 942-948.

- Thomas R: Prevalence of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2015; 135; 4.

- German Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry PuP: Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in infancy, childhood and adolescence. 3. rev. ed. and erw. ed. Cologne: Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag 2007.

- Romanos M, et al: Diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood and adolescence. Neurologist 2008; 79: 782-790.

- Jans T, et al: Therapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood. Neurologist 2008; 79: 791-800.

- Sonuga-Barke E, et al: Nonpharmacological Interventions for ADHD: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials of Dietary and Psychological Treatments. Am J Psychiatry 2013; 170: 275-289.

- Walitza S, et al: The school child with ADHD. Ther Umsch 2012 Aug; 69(8): 467-473.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(3): 24-27.