Influenza virus infection is a highly contagious disease that is transmitted through the air. It usually causes an acute febrile illness with general symptoms of varying severity, but is primarily a self-limiting viral illness. An overview also of special features of in children in diagnosis, therapy and prevention in this annual recurring disease.

Influenza virus infection is a highly contagious disease transmitted by droplets. It causes an acute febrile illness with general symptoms of varying severity, is mainly but not always a self-limiting viral illness. Seasonal influenza occurs regularly in our region between December and March. The duration of the flu epidemic is usually six to eight weeks. Each flu epidemic is unique in terms of intensity, duration, age distribution, circulating virus strains, and the public health impact it has. In Switzerland, 5-10% of the population contract the disease each year. In one season, influenza causes about 100,000 to 270,000 physician visits (Sentinella surveillance system), 1000 to 5000 hospitalizations, and up to 1500 deaths. These are mainly high-risk patients. A certain number of unreported cases must be assumed, since not every case of influenza is recognized or detected. In humans, the disease is caused by influenza viruses of types A and B, and rarely by type C.

Review of the 2016/2017 influenza season in Switzerland

In all age groups, influenza A viruses of subtype H3N2 (98%) were predominantly responsible for the illnesses. The subtype distribution of influenza viruses was similar in all regions, with primarily influenza A viruses of subtype H3N2 found. In the southeast (GR, TI), influenza B viruses of the Yamagata lineage and influenza A viruses of the H1N1pdm09 subtype were more frequent compared with other regions, but also significantly less frequent than influenza A viruses of the H3N2 subtype. In terms of age distribution, the highest overall incidence, 5266 influenza-related physician consultations per 100,000 population, was recorded among 0-4 year olds.

Infection route

Influenza viruses are predominantly transmitted by droplets with a particle size of more than 5 μm, which are produced in particular during coughing or sneezing and can reach the mucous membranes of the respiratory tract of contact persons over a short distance. Individual publications also suggest the possibility of aerogenic transmission through so-called droplet nuclei, which are smaller (<5 μm), are also formed during normal breathing or speaking, and can remain suspended in the air for longer periods. In addition, transmission is also possible through direct contact of the hands with surfaces (e.g. by shaking hands) contaminated with virus-containing secretions and subsequent hand-mouth/hand-nose contact.

Incubation period

The incubation period is short, averaging two days (between 1-4 days).

Clinical symptoms in childhood

The clinical presentation of influenza varies with age. The following typical influenza symptoms are usually seen in older children: Sudden onset of illness, fever, sore throat, myalgias, frontal/retroorbital headache, rhinitis, feeling of weakness and severe fatigue, cough and other respiratory symptoms, tachycardia, pharyngitis, and red, watery eyes. In young children and especially in infants, the clinical picture may be quite different and may manifest itself, for example, only as weakness in drinking, drowsiness, vomiting, shortness of breath, or only as fever.

Differential diagnosis

Rhinoviruses, respiratory syncytial viruses, human metapneumoviruses, other virologic respiratory pathogens, or mycoplasmas may present clinically in a very similar manner. A parallel frequency of infection in the winter months can also be observed here, making differential diagnosis more difficult.

Diagnostics

A reliable differentiation can only be made by laboratory diagnostics. However, this is not considered useful in everyday practice, since during the peak phase of an influenza wave and during epidemics, the typical influenza symptoms can be diagnosed with sufficient probability in most patients on the basis of the clinical presentation, and virus detection by means of a rapid test does not lead to any real “benefit” in everyday practice. The sensitivity of rapid influenza tests is only good to moderate, depending on the influenza type or subtype. With a relatively high specificity, a positive rapid test during an influenza epidemic has a high significance, but negative tests do not exclude influenza. In principle, the hit probability of a positive laboratory test decreases continuously after the first two days of illness. Swabs from the nose have a higher sensitivity than samples from the throat.

Conclusion for diagnostics in practice

Rapid tests do exist, but due to cost, availability, sensitivity, and most importantly the lack of relevant added value in everyday practice, the diagnosis of influenza should be based on clinical criteria alone.

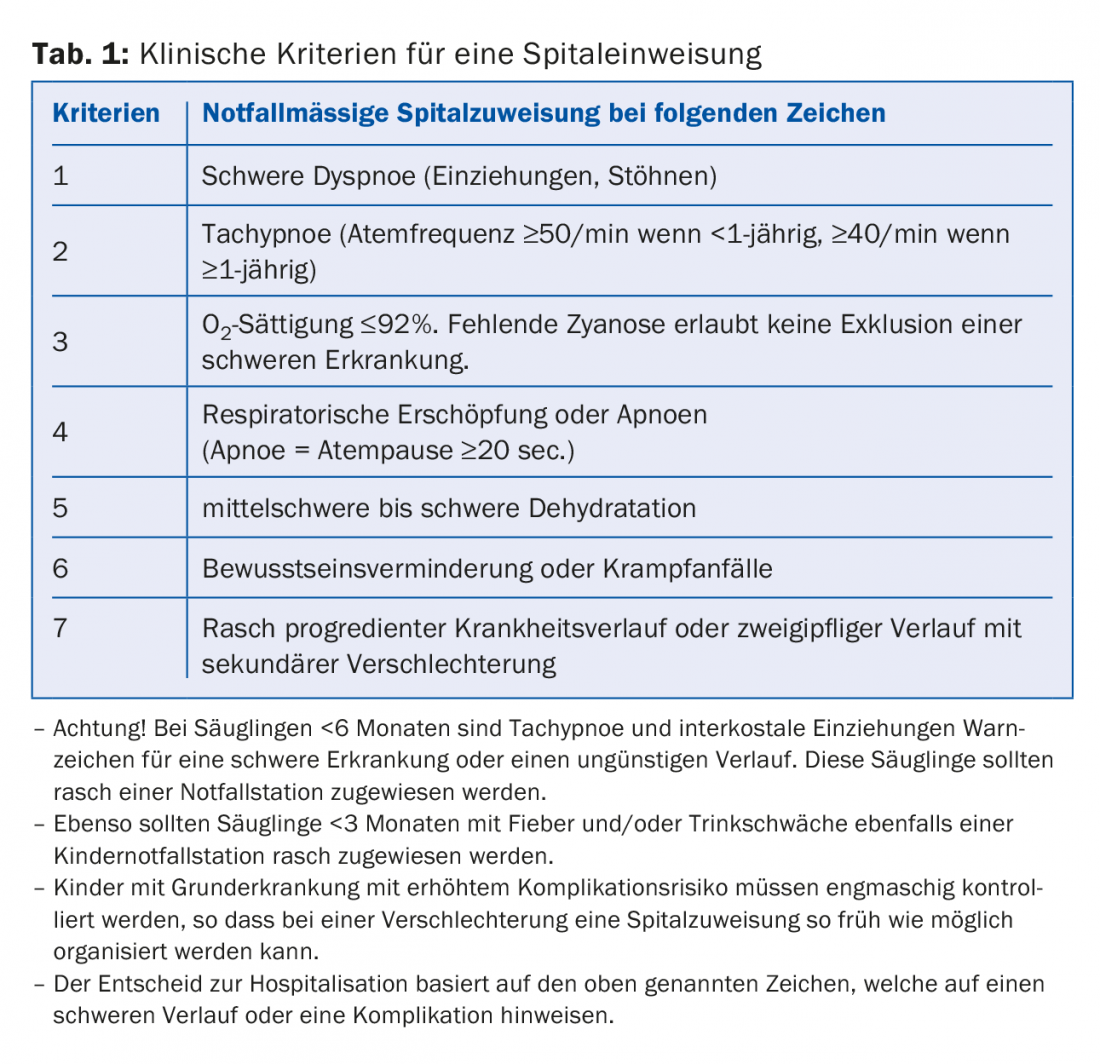

This makes it all the more important in everyday practice to identify those children who need to be hospitalized. Table 1 shows the clinical criteria for hospitalization.

Duration of contagiousness

The duration of infectivity is on average about 4-5 days from the onset of the first symptoms, but is also possible before the onset of symptoms. However, a longer duration of up to seven or more days is possible, especially in children or patients with a severe course.

Course/Complications

Rarely, severe courses occur. High-risk” patients are particularly affected.

Worsening often occurs about 3-10 days after symptom onset. Pulmonary complications are prominent: primary influenza pneumonia due to the virus itself, secondary bacterial pneumonia (including pneumococci, staphylococci, Haemophilus influenzae), or exacerbations of chronic lung disease.

Other rare complications include myositis, rhabdomyolysis, myocarditis. Severe neurologic complications of influenza occur predominantly in childhood in the form of

febrile convulsions but also encephalopathies. In fact, in Japan, influenza is the most commonly detected agent in acute encephalopathy.

A milder but common complication of influenza in children is otitis media.

Therapy

Treatment of those who do not belong to the risk groups and in uncomplicated cases should be symptomatic. General symptomatic measures such as nasal care, antipyretic measures/medications, and avoidance of physical exertion are sufficient. Administration of acetylsalicylic acid is obsolete in influenza-infected children because of its association with the rare but dangerous Reye syndrome.

Antiviral therapy is considered in children only in high-risk patients with a severe hospital course. Even in this case, the indication is extremely strict and always in consultation with an infectiologist.

Prevention

Active immunization is the cornerstone of prevention. This reduces morbidity, mortality, and hospitalizations in at-risk groups. Current vaccination recommendations are discussed in the second article in this focus by Dr. Eckert et al. listed.

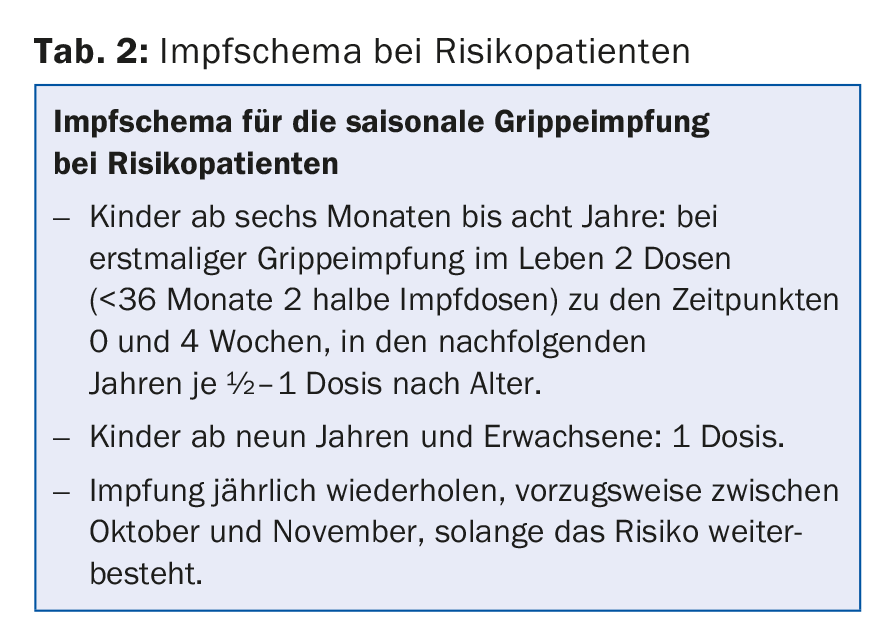

The vaccination schedule in children who are at risk, depending on their age, is summarized in Table 2.

Take-Home Messages

- The clinic varies greatly in children depending on their age. The younger the child, the more atypical the symptoms.

- Diagnosis is made in the office using clinical criteria rather than the rapid influenza test.

- In most cases, it is a self-limiting viral disease that does not require targeted therapy.

- Acetylsalicylic acid as an antipyretic should be avoided in children because of its association with Reye syndrome.

- Antiviral therapy should be initiated only in the hospital under very strict criteria.

- “Don’t miss Redflags. These children need to be hospitalized promptly.

- Close monitoring of patients at risk in order not to miss a possible deterioration.

- Active immunization of patients at risk is the main pillar of prevention.

Further reading:

- Federal Office of Public Health FOPH: Seasonal Influenza – Situation Report Switzerland. 2017; www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/themen/mensch-gesundheit/uebertragbare-krankheiten/ausbrueche-epidemien-pandemien/aktuelle-ausbrueche-epidemien/saisonale-grippe—lagebericht-schweiz.html

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Seasonal Influenza – Latest surveillance. 2017; http://flunewseurope.org/

- WHO – Recommended composition of influenza virus

- vaccines for use in the 2017-2018 northern hemisphere influenza season. 2017; www.who.int/influenza/vaccines/virus/recommendations/201703_recommendation.pdf?ua=1

- Paediatric Infectious Disease Group of Switzerland PIGS – Triage recommendation for admission and retention of children in the ICU during pandemic influenza. 2017;

- www.pigs.ch/pigs/05-documents/doc/triage-2010-d.pdf

- Paediatric Infectious Disease Group of Switzerland PIGS – Recommendations for the management of children with suspected pandemic influenza (H1N1) 2009; www.pigs.ch/pigs/02-news/doc/grippe-empfehlung(alt).pdf.

- COMMITTEE ON INFECTIOUS DISEASES: Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2016-2017. Pediatrics 2016; 138(4). pii: e20162527.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. 2017; www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm

- CDC Recommendations for the amount of time persons with influenza-like illness should be away from others. 2011; www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/guidance/exclusion.htm

- Murray JS: Prevention and control of influenza in children during the 2016-2017 seasonal epidemic. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2017; 22(2).

- Ortiz-Lana N, et al: [A prospective study to assess the burden of influenza-related hospitalizations and emergency department visits among children in Bilbao, Spain (2010-2011)]. An Pediatr (Barc) 2017; pii: S1695-4033(16)30338-1.

- Leekha S, et al: Duration of influenza A virus shedding in hospitalized patients and implications for infection control. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007; 28(9): 1071-1076.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to express his sincere thanks to Prof. Dr. med. Christoph Berger FMH Infectiology and FMH Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Head of the Department of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Hygiene at the Children’s Hospital Zurich for the critical review of the article and the valuable and enriching input.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(11): 7-10