Risk states for schizophrenia are defined mainly by attenuated psychotic symptoms and subjectively perceived changes in perception and thinking. In a high-risk state, supportive care and monitoring, rather than antipsychotic treatment, are primarily indicated. In the case of manifest psychosis, multimodal treatment with pharmacotherapy (with antipsychotics), psychotherapy, and rehabilitation should be provided promptly, as prolonged duration of untreated psychosis has a negative impact on the course of the disease and the patient’s everyday functioning.

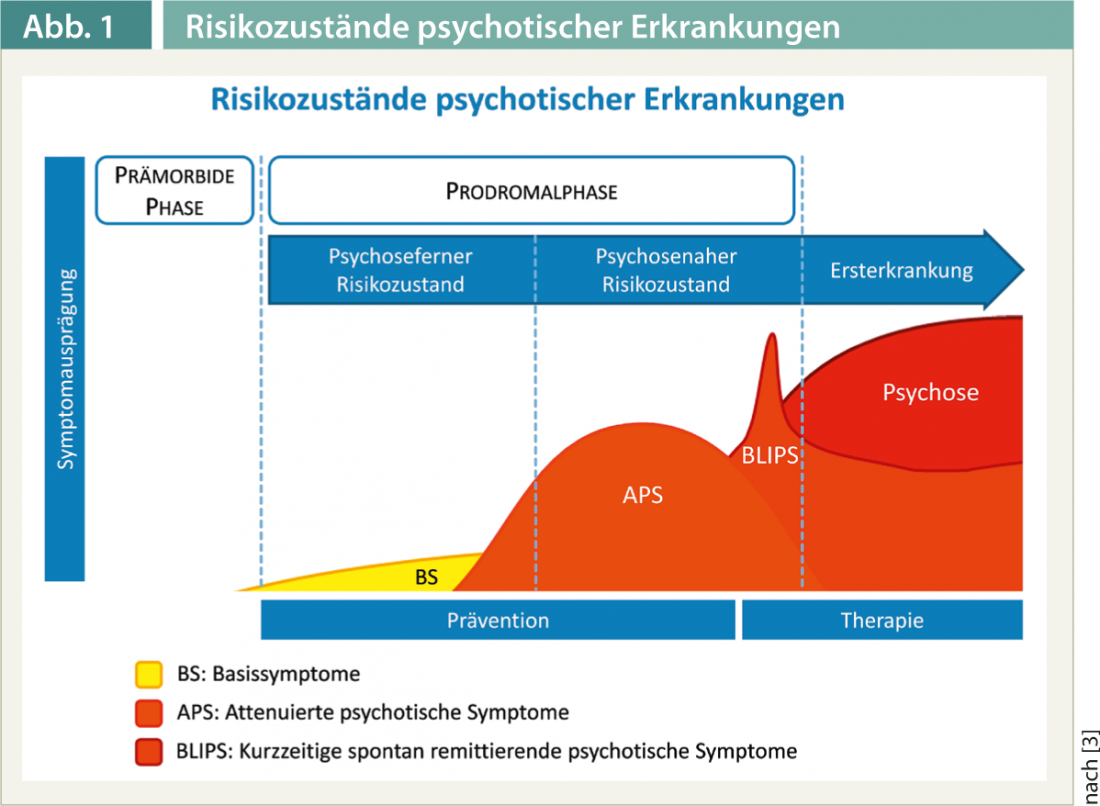

Schizophrenic psychoses are severe mental illnesses that are often associated with a persistent loss of quality of life and everyday function [1]. In the period shortly before and in the course of the first psychotic phase, decisive decisions are made for the further development of the illness [2]. In a majority of affected persons, nonspecific symptoms occur in the run-up to a manifest schizophrenic illness (fig. 1).

This is where the early detection of psychoses in the sense of secondary prevention comes in. It is therefore aimed at people who are already burdened by symptoms and seek counseling and help because of them. Thus, the task of early detection is not only to assess the risk of psychosis and, ideally, to prevent its transition into a manifest illness, but also to treat the symptoms that are already present.

Risk assessment

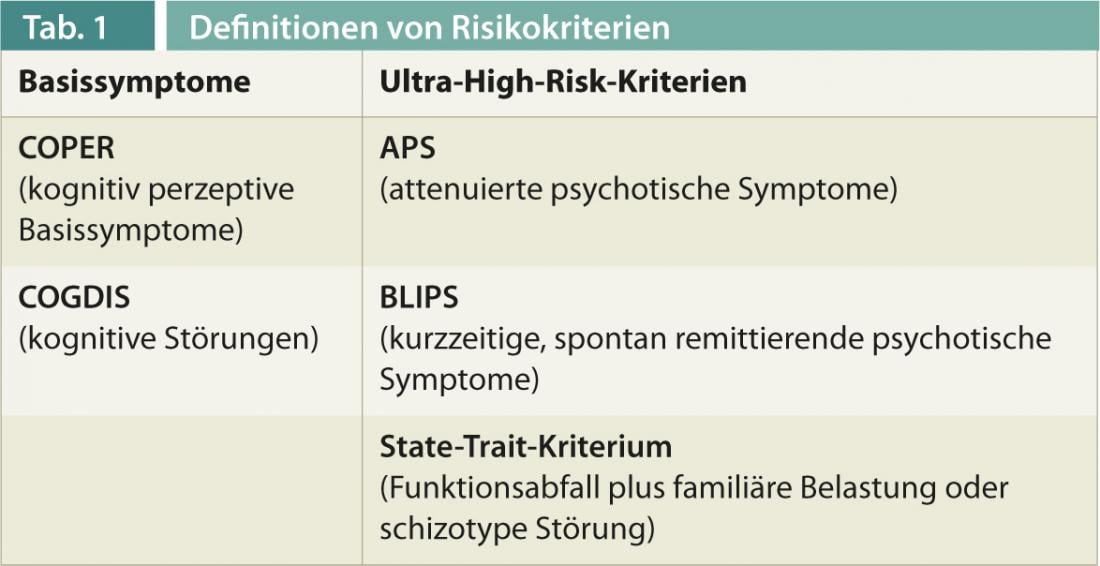

Well-established definitions of risk criteria now exist for assessing psychosis risk (Table 1) [3]. Currently, there is a trend to use two different approaches in parallel. One approach is primarily aimed at determining the risk of an imminent transition to manifest disease. This more psychosis-related risk state is described, for example, by the ultra-high-risk criteria. These are based on the presence of attenuated psychotic symptoms or the short-term appearance of clear psychotic symptoms that resolve without specific treatment. Ultra-high-risk criteria are also met when there is a significant decline in functional level and concurrent genetic burden of psychosis in a close relative or schizotypal personality disorder in the individual. The other approach already captures the “early” psychosis-remote risk state. It is based on the so-called basic symptoms, which include disturbances in thinking and changes in the perception of the self and the environment subjectively perceived by the affected person.

According to a meta-analysis, if the risk criteria are met, individuals are at approximately 32% risk of transitioning to manifest schizophrenic disorder within the next three years [4]. However, this also means that about two-thirds of those in the at-risk state do not develop manifest schizophrenia within the three years. However, the individual studies showed a wide variation in transition rates. Interestingly, transition rates were lower in the more recent studies, which, in addition to dilution effects due to the inclusion of individuals at lower risk for psychosis, may also be interpreted as evidence of successful treatment of high-risk individuals.

As the transition rates show, the presence of a risk state is not necessarily a prodromal symptom of schizophrenia. There is also a great deal of overlap with other, non-psychotic disorders. About 40% of individuals at risk for psychotic illness simultaneously met diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode and about 15% for an anxiety disorder [5]. In the spirit of the desired symptom reduction, such additional disorders should be treated in an appropriate manner, e.g., by administration of antidepressant medication.

Supportive therapy

According to a current consensus recommendation, individuals in the at-risk state should generally receive supportive therapy focused on their current individual needs. In addition, the use of cognitive therapy techniques and omega-3 fatty acids are evaluated as helpful. Antipsychotic medication is not currently recommended in the at-risk state because current studies show no advantage for antipsychotic treatment, compared with other treatments with fewer side effects [6]. In individual cases, however, the use of antipsychotics can lead to a reduction in symptom burden even in the at-risk state. Drug treatment should be carefully considered and should not be given merely because criteria for psychosis risk are met.

Monitoring and recovery

Another essential task of early detection is the regular monitoring of mental findings, so that in cases where it is not possible to prevent the onset of a manifest disease, appropriate treatment can be initiated without delay. This is particularly important because prolonged duration of untreated psychosis has a negative impact on further symptom development and everyday functioning [2]. Therefore, there is consensus that treatment as soon as possible is indicated for manifest psychotic illness. With regard to treatment goals, the focus is no longer only on symptom control and relapse prophylaxis, but recovery in the sense of everyday function and subjective quality of life is becoming increasingly important. This is accompanied by the development of integrated therapeutic approaches that place great emphasis on psychotherapeutic and rehabilitative procedures in addition to antipsychotic treatment.

Pharmacotherapy

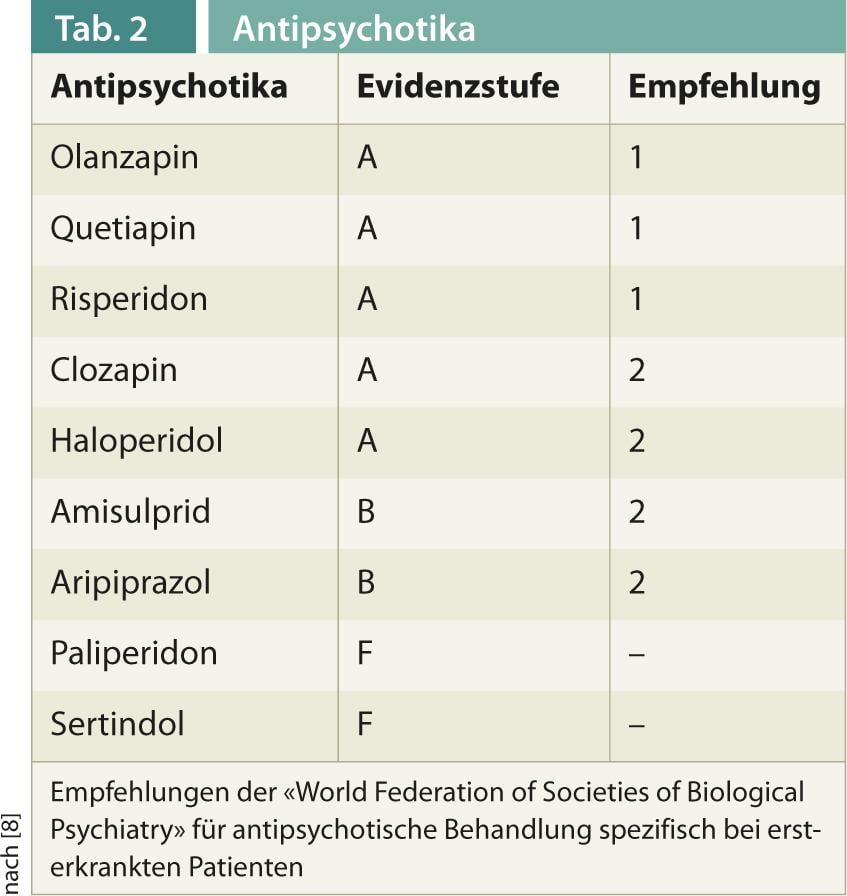

Regarding pharmacotherapy, there is consensus that antipsychotic therapy should begin as early as possible in manifest psychosis. Specifics in first-time sufferers include higher response rates even at low doses, but also increased susceptibility to side effects. No consistent position is taken by the different international guidelines regarding the preference for atypical over typical antipsychotics. Efficacy differences appear to be less pronounced than hypothesized [7]. Typical antipsychotics are more likely to cause extrapyramidal motor side effects, and atypical antipsychotics are more likely to cause weight gain. At the same time, it must be noted that atypical antipsychotics represent a heterogeneous group of drugs. Thus, the guideline of the “World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry” gives a differentiated recommendation based on studies specifically in first-episode patients (Tab. 2) [8].

Psychotherapy

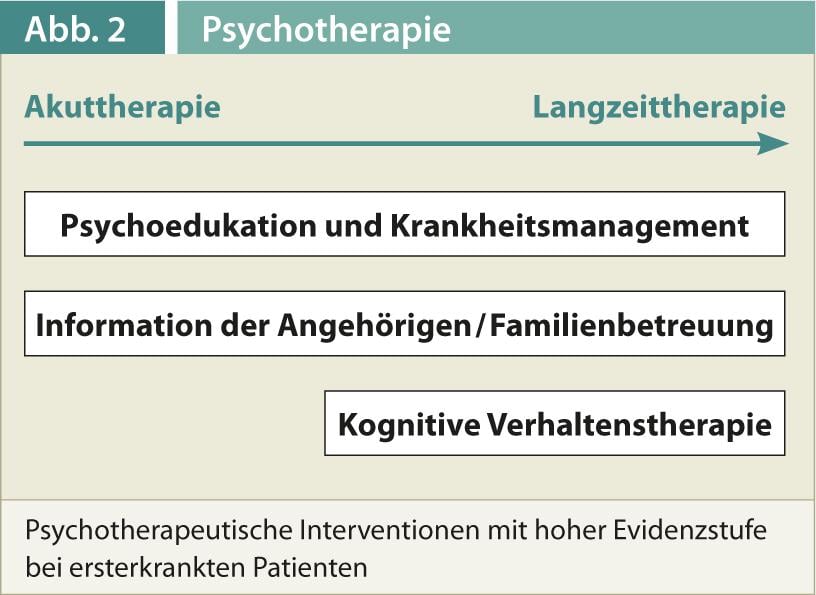

Psychotherapeutic procedures for initial manifestations of psychosis include different approaches (Fig. 2) [9]. An essential element is psychoeducation, the goals of which include developing a concept of the disease, promoting adherence to therapy, dealing with the disease, and ultimately developing a positive outlook on life. Psychoeducation is offered in a variety of forms and settings, with a group format offering advantages in working through issues together.

Another pillar is the work with relatives. Here, there are approaches ranging from providing information to working on intra-family communication to long-term family support. Although good evidence exists for working with relatives, selecting specific interventions within these approaches remains difficult. There is now also good evidence for psychotherapeutic interventions in the narrower sense, although almost exclusively approaches based on cognitive behavioral therapy have been studied. In addition to form and setting, studies also differ in their goals, which include relapse prevention, management of persistent symptoms, improvement of daily functioning, and coping with the experience of psychosis. The majority of the studies were conducted in individual settings, but also in group settings, and generally involved 16-20 hrs.

Rehabilitation

With an increasing focus on patients’ everyday function, rehabilitative procedures are gaining importance. It must be noted that there are few empirical studies in this regard for the group of first-episode patients with psychosis. An exception is the supported employment approach, in which patients are accompanied by a job coach in their direct search for work in the labor market and then in the workplace [10]. In Switzerland there are numerous other offers of occupational and everyday rehabilitation, which are profitably used in practice. Here, further empirical evaluation would be desirable with regard to first-episode patients in order to be able to select such offers in a more targeted manner.

Conclusion

Overall, the field of early detection and treatment of schizophrenic psychoses shows a dynamic development, which raises hope that in the future our patients will have fewer limitations due to the consequences of these disorders. However, this rapid development in diagnostics and in pharmacological, psychotherapeutic and rehabilitative treatment also poses a challenge that can hardly be met by individual actors in the healthcare system. In order to be able to optimally care for patients at this critical point in their development, increased cooperation between physicians in private practice, clinics and rehabilitation facilities will be necessary in the future.

Literature list at the publisher

PD Dr. med. Karsten Heekeren

PD Stefan Kaiser, MD