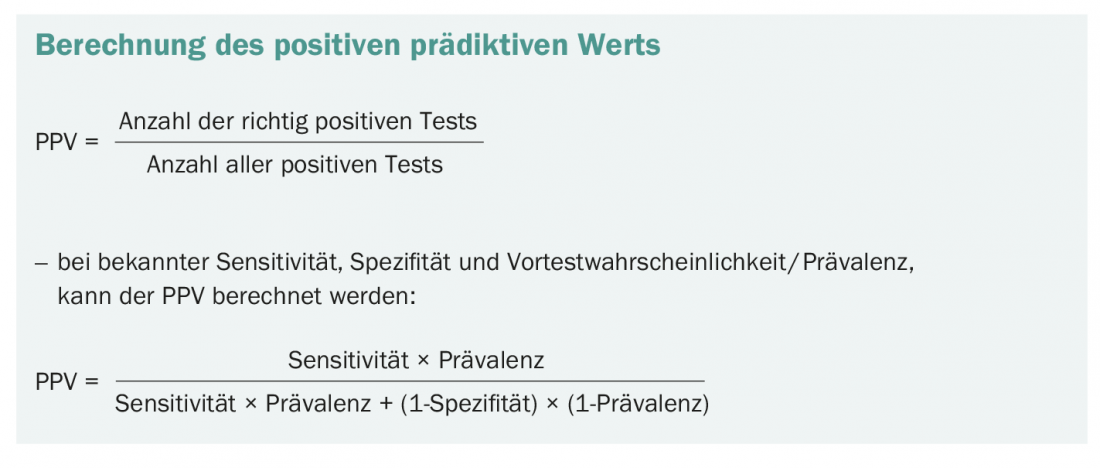

The positive predictive value is of great importance in the interpretation of medical tests. For example, someone who tests positive for SARS-CoV-2 is not necessarily infected. The question of the probability of such a positive test result actually being correct is answered by the positive predictive value. And thus contributes significantly to the correct handling of test results – if it is taken into account.

PPV = 0.5. Or put another way: “You have received a positive test result. The probability that you are actually ill is 50%.” With this statement, many a test takes on a somewhat debilitating flavor. However, it is only by considering the significance of a positive test result that it can be dealt with sensibly. Thus, surgery, quarantine measures, or administration of strong drugs based on a test with a low positive predictive value clearly seem excessive, whereas they may be justified if the PPV is high.

Depending on many factors

In addition to the sensitivity and specificity of a test, the pre-test probability in particular is decisive for the positive predictive value. This is often equated with prevalence, but of course varies in different populations and with different symptoms. For example, if an asymptomatic person is tested for Sars-CoV-2, their pre-test probability of being infected with the virus is significantly lower than if someone with a cough and fever takes the same test. At the same time, the pretest probability in the overall population is greater in periods with higher numbers of cases than in periods with few infection events. Which brings us to another hotly debated topic: The dilemma of screening examinations. If screenings are performed in populations where disease is very rare, the positive predictive value becomes very low. Thus, selecting the right population contributes significantly to the validity of screening examinations.

A small example

If a screening procedure has a sensitivity of 99% and a specificity of 99.5% – both respectable values – and if the prevalence in the test population is 0.01, the positive predictive value is 0.667. In 66.7% of those who tested positive, the disease they were looking for was actually present. Now, using the same test, we examine a population in which the prevalence is much lower: 0.0001 or 1/10,000. The positive predictive value is now 0.019, which means that only just under 2% of positive test results are correctly positive.

The bottom line is that it’s not just the test itself that matters how meaningful it is, but also the circumstances under which it is tested. What is the overall frequency of a disease? And does the clinical impression indicate the presence of some disease? Is there an accumulation in the family? Or was there contact with infected individuals? And one more conclusion: diagnostic activity can by no means be replaced by standard testing, not even with more and more available test procedures. This is because the crux often lies in the interpretation and indication.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2021; 9(4): 38.