ADHD can be treated well. Multimodal therapy has the best evidence of efficacy. However, diagnosis is often complicated by a wide symptom variance. In addition to other factors, hormonal fluctuations can also influence symptoms and coping strategies.

Many patients turn to their primary care physician or psychiatrist with questions about the assessment or treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The wide symptom variance often complicates diagnosis. In addition, hormonal fluctuations and cross-cultural expectations can also influence the severity of symptoms and the way patients cope with the disease.

The genders also differ in terms of course, development of comorbidities, and treatment. This article is intended to provide an overview of the specifics. In the article, only the masculine form is used in part for reasons of readability.

ADHD symptoms and epidemiology

The psychiatric disorder ADHD belongs to the neural developmental disorders. The diagnosis is made when a certain number of the three core symptoms (hyperactivity, impulsivity, and attention deficit disorder), as well as secondary criteria such as emotional fluctuations and impairments in executive functions, can be demonstrated in severity relevant to everyday life. A multicausal disorder model is thought to include epigenetic, prenatal, and psychosocial factors. Well studied is the influence of very active dopamine back transporters (mainly in the prefrontal cortex and limbic system) and a resulting dopamine deficiency in the synaptic cleft [1]. Prevalence rates of just under three percent in adults are found worldwide, and the diagnosis is four times more common in boys [2].

It is assumed that ADHD tends to remain undetected in girls, since the current diagnostic systems (ICD-10) query the symptoms that are more obvious in boys (such as hyperactivity), and that in girls the symptoms express themselves differently or unmask later. Some meta-analyses exist for children and adolescents with ADHD that specifically looked at sex differences [3]. These consistently showed that female ADHD patients had fewer primary symptoms (hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity) and fewer externalizing problems than male patients. In addition, a strong rater bias is evident in the assessment of ADHD in girls compared with boys. Doctors more easily diagnose ADHD in boys, so this is likely to leave many female sufferers undiagnosed [4,5]. These gender-different phenomena are also discussed in terms of possible misdiagnosis, as only 6.6% of girls but 21.8% of boys are falsely positively diagnosed with ADHD due to errors in diagnostic judgment. In addition, false-positive diagnoses were significantly more frequent overall at 16.7% than false-negative diagnoses at 7% [6]. The DSM-IV first created subgroups with predominant symptoms of inattention, and a DSM-IV survey found a more balanced gender ratio, with a prevalence of 3.2% in females and 5.4% in males [7]. In the presence of a comorbid intellectual developmental disorder, the point prevalence is significantly increased, averaging 12% [8]. Interestingly, the gender distribution is then about the same [9]. Other congenital syndromes are also particularly frequently associated with ADHD, e.g. trisomy 21 (Down syndrome, 34-44%) [10], Fragile X syndrome (40-49%). [11], Williams syndrome (65%) [12], alcohol embryopathy (FASD, 51%). [13], 22q12 syndrome (34%) [14] and Duchenne muscular dystrophy [15]. ADHD often occurs in autistic individuals, with one in two also meeting DSM diagnostic criteria for ADHD [16]. During the course of development, the symptoms may remit completely or partially; a distinction is made between rare full remissions, frequent partial remissions, and very few persistent courses without a reduction in symptom expression. Most adults suffer from at least some of the symptoms throughout their lives, which can lead to severe effects in all areas of life. Particularly in males, the prevalence of ADHD gradually decreases over the lifespan. ADHD symptomatology persists more frequently and more severely in women, patients with comorbidities, and individuals with intellectual developmental disabilities [17,18]. Difficult family relationships and low social skills also decrease the remission rate [19]. The best predictor of remission in adulthood appears to be high IQ and a good psychosocial environment [20].

Biederman differentiates between current and lifetime diagnoses in a study. While with regard to lifetime diagnoses, men were found to have more substance use disorders and dissocial personality disorder, and women were found to have more panic disorder, only one difference was found for current diagnoses. Males with ADHD had higher rates of substance use disorders than the females with ADHD and, in some cases, more comorbid childhood behavior disorders [21].

In adulthood, most commonly diagnosed are personality disorders or accentuation, substance abuse, affective disorders, anxiety disorders, sleep disorders, and tic disorders. In childhood, oppositional behavior disorders, attachment disorders, tic disorders, anxiety disorders, and affective disorders are most common [22]. Girls and women are often diagnosed with ADHD after the onset of comorbid conditions.

A longitudinal study of women with ADHD showed remission in only 23% of participants after 11 years. Personality disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorders continued to increase over the complete period. Overall, most women experienced significant impairments in education and employment [23]. Women with ADHD are five times more likely to be diagnosed with major depression than women without ADHD [24]. Ottonen showed in a large study that overall psychiatric comorbid conditions were more common in women with ADHD than in men. Here, a gender comparison showed that certain comorbid disorders occur less frequently in women (dyslexia, delinquency, oppositional behavior) and others more frequently (anxiety, affective disorders, eating disorders, substance abuse) [25]. Whether this is more likely to be due to external or internal factors is as yet insufficiently documented. There is debate as to whether early diagnosis and treatment in male patients reduces the development of comorbid disorders. Another explanation could be that women with mild forms of ADHD go undetected and the severe cases, which correlate more with comorbidities, are diagnosed more often in women. Regardless of gender, the risk of dying earlier and also by non-natural means increases; patients with a late diagnosis and those with concomitant psychiatric illnesses are particularly at risk [26].

The consideration of examining ADHD on a gender-specific basis is not new; Nadau published A comprehensive guide to Attention Deficit Disorder in Adults as an editor in 1995, which already included a chapter entitled “Special considerations for symptomatology in women,” and also developed special questionnaires for women [27]. However, diagnostic workup continues to be performed equally in men and women. Johanna Krause, in the book ADHD in Adulthood, points out that when mothers have children with ADHD, it is important to remember that the mothers may also have ADHD [28]. In a controlled double-blind study of affected mothers and children, mothers treated with methylphenidate significantly improved parenting style compared with the placebo group, were more consistent, and were less inclined to be physically punitive [29]. Patients appreciate recommendations on gender-specific literature [27,30,31]. The following symptoms seem to be more specific to women:

- Later appearance (or becoming visible) of the symptoms

- Self-blame, low self-esteem

- Increased sadness/baseless anxiety

- Internal conflict resolution (under stress “implode instead of explode”)

- Difficulties are denied; there is a desire not to stand out

- Tendency to engage in oral behaviors under stress: thumb sucking, nail biting, overeating (sometimes with vomiting), smoking.

- Gravitational reinforcement during puberty

- More intense pain experience, hypersensitive to stimuli.

- Blockade and withdrawal to requirements

- Pronounced premenstrual syndrome

- Violent reactions to added hormones

Diagnostics for girls and women

Differences are found in the diagnostic criteria in the ICD (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems) and DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), where one finds a division into subtypes. Two subtypes can be distinguished: In the combined type, women appear outwardly eloquent-self-confident, oversocial, very busy, and charismatic despite chaotic lives. In the inattentive type (this is the more common type in women), they seem more withdrawn to socially isolated, appearing shy and quickly discouraged. Daydreaming leads to procrastination and falling short of professional opportunities. From the outside, they are perceived as lethargic and passive, despite good intentions. Moreover, the higher the IQ, the more difficult it is to recognize the symptomatology, since a good facade masks the underlying cause, and women suffering from ADHD are masters at learning avoidance tactics and coping strategies. In part, these patients seem obsessive, fastidious, and chronically exhausted because all their energy is used to cope with everyday life. These patients often state that they are trying to conform to a traditional role model and the role expectations that come with it. It is well known that ADHD symptoms that are considered more typical in boys (strong motor activity, being loud, being a tease, acting impulsively) are more quickly perceived as inappropriate and disruptive in girls and are structured and regulated earlier from the outside. This also means that they are often noticed less or only later.

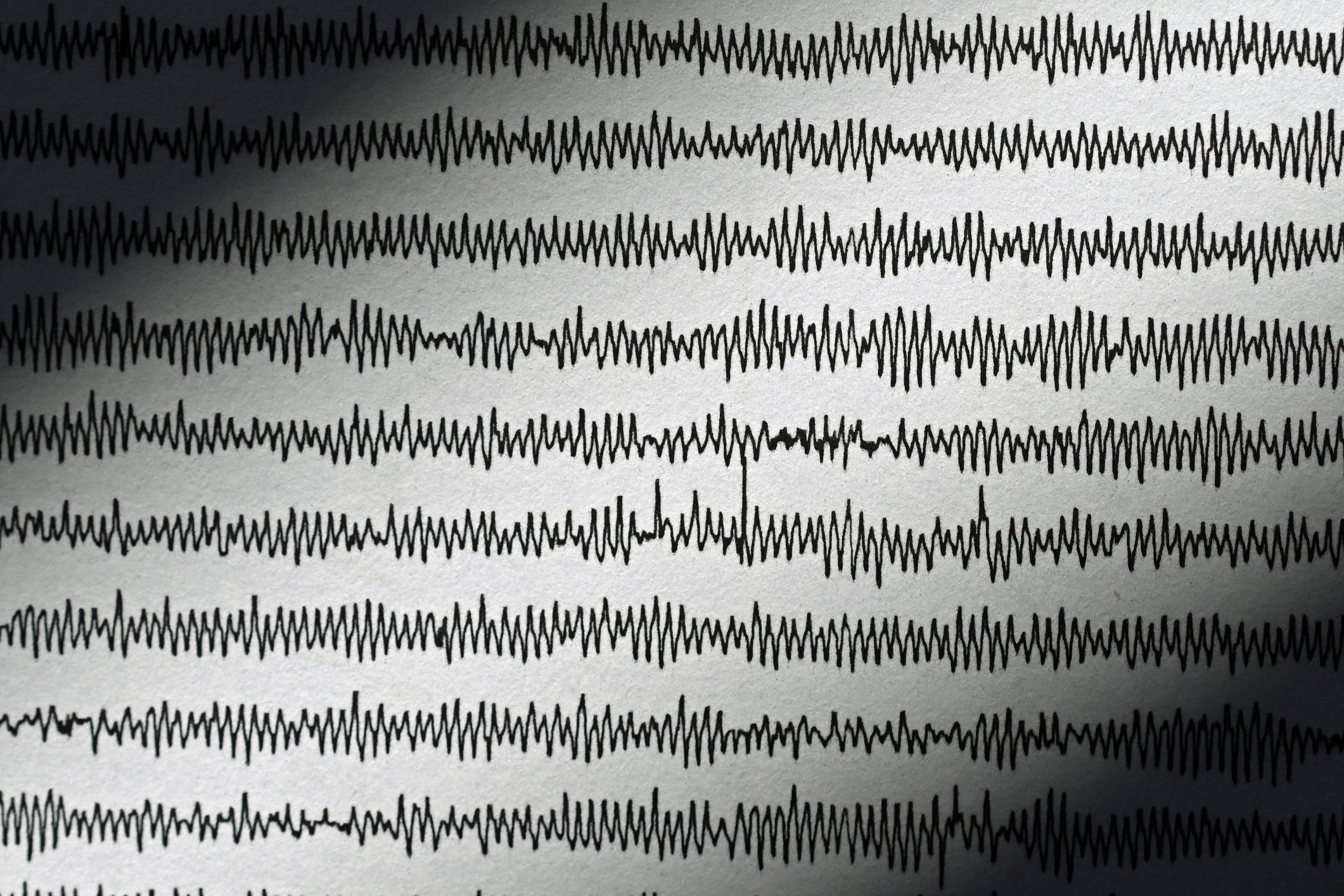

Despite numerous epigenetic studies, no biomarker for ADHD has yet been found, so the diagnosis remains a purely clinical one [32]. If this disorder is suspected, the diagnosis is made by means of a standardized interview with a detailed medical history and also a history from others (in the case of minor patients also with the parents, if possible), and a retrospective survey of symptoms from childhood (Wender Utah Rating Scale, WURS-K) and review of old records (e.g., report cards) [33]. The Brown ADD Scale and the Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS) can be used as questionnaires [34,35]. Behavioral assessments and probationary treatment trials with methylphenidate are not mandatory, but may provide valuable diagnostic clues in individual cases. It is also possible that the application of characteristics recorded in the EEG (“diagnostic classifiers”) can support the diagnostic process [36]. Symptom catalogs created specifically for women (e.g., the ADHD Self-Rating Scale for Women by K. Nadeau and P. Quinn) proved helpful [27]. Although these do not serve to establish a diagnosis according to ICD or DSM, they can be easily handed out to women in the general practitioner’s office in order to ascertain the degree of expression of typical symptoms. There is often a surprised self-awareness and the statement “I thought they were writing about me.”

Female hormones and ADHD

With the onset of puberty (hormonal transition), symptoms become more intense and, in some cases, altered as the female sex hormones estrogen and progesterone interact with the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin.

Situations of hormonal changes (menarche, menstrual cycle, pregnancy, menopause) are an energy-consuming process for every woman, which can be accompanied by impairment of psychological well-being [37]. Women with ADHD seem to show stronger hormonal fluctuations or react more sensitively, violently and problematically to these fluctuations. Estrogens and progestins have a strong influence on CNS neuronal activity, modulating synthesis, release, receptor binding, and reuptake of neurotransmitters. Estrogens generally have an activating effect on the CNS, whereas progestins have a depressing effect. They have a positive effect on mood and well-being, presumably by enhancing serotonin and dopamine activity. Accordingly, they may lead to alteration of ADHD symptomatology, but also psychopharmacological effects associated with the noradrenergic and dopaminergic systems. Endorphins (which in turn are stimulated by estrogens), for example, inhibit the release of norepinephrine and dopamine. Therefore, a drop in estrogen concentration (premenstrual, postpartum, menopause) can lead to a rebound-like increase in dopamine and norepinephrine, resulting in increased CNS excitability and irritability. Estrogen deficiency can lead to impairment of the cholinergic, dopaminergic, and serotoninergic systems and loss of synaptic connections independent of ADHD. This can result in cognitive performance losses. The influence of estrogen on the dopaminergic system occurs mainly in the hypothalamic region. There are estrogen receptors in the limbic system that have a “neuromodulator function.” They modulate the sensitivity and number of dopamine receptors. This shows a close relation to the neuroprotection hypothesis, which is also known for other mental diseases. The hormonal influence is shown in the different situations as follows [37]:

Menarche and cycle:

- An above-average number of girls and women with ADHD have severe and prolonged premenstrual syndrome.

- Often there are strong cyclical changes in mood and well-being.

- There is a higher than average risk for early sexual activity and early pregnancy, as well as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

- Additionally, there is an increased risk for changing, unsatisfying, brief relationships or experiencing sexual violence.

Puberty and adolescence: Prefrontal maturation plays a crucial role in puberty, but also in ADHD symptomatology. Hormonal fluctuations and problems occur

- in planned, forward-looking action,

- in recognizing the consequences of increased risk-taking,

- in the perception of one’s own feelings and the feelings of others,

- in feeling rewards (i.e., teenage girls would have to do more dangerous things to feel the same thrill) with less opportunity for reward deferral.

Pregnancy, maternity:

- Often there is a reduction in ADHD symptoms due to increased estrogen levels or the absence of cyclical hormonal fluctuations.

- Postpartum hormonal changes and serious changes due to living with a child with increase in ADHD symptoms.

- Also: ADHD is usually inherited; a child who also has ADHD presents another challenge for the mother.

Menopause: entry into menopause and end of fertility.

- A drop in natural estrogen production increases ADHD symptoms; these are often initially confused with menopausal symptoms.

- Negative impact on cognitive functions.

Therapy for girls and women

ADHD is usually well treatable with a multimodal approach (medication, psychoeducation, psychotherapy, etc.). In the S3 guideline, the treatment of ADHD is differentiated by severity. In the case of a mild severity, mainly psychosocial treatment should be offered; in the case of a moderate severity, intensified psychosocial and/or pharmacological intervention should be offered after psychoeducation, depending on the concrete living conditions; in the case of a severe form, pharmacotherapy is the main focus [38,39]. The effects of the various ADHD medications have been well studied in both women and men, in children and in adults, showing high effect sizes and good response rates.

A review included 133 studies with a total of 14,346 children and adolescents and 10,296 adults and examined the efficacy and safety of 12-week treatment with amphetamines, atomoxetine, bupropion, clonidine, guanfacine, methylphenidate, and modafinil versus each other or versus placebo. The authors consider methylphenidate in children and adolescents and amphetamines in adults to be the therapy of choice in the first-line treatment of ADHD. In addition, the results of the network analysis demonstrate that careful monitoring of body weight and blood pressure changes is important with all ADHD treatment medications [40].

Because severe cycle-related fluctuations and PMS can occur in ADHD, patients should be educated about this phenomenon and the possibility of hormonal therapy. Of course, women without ADHD can also benefit from hormonal support. In all patients, always under the risk consideration that includes hormonal administration (e.g., with respect to increased thromboembolic risk). Special attention should be paid to possible interactions when combining different drugs (e.g. stimulants and estrogens). Long-acting preparations that maintain hormone levels as constant as possible are recommended. Orally taken hormones (“birth control pill”) for contraception can be taken well continuously after consultation with the gynecologist or other substitution types such as hormone rings, depot injections or hormone implants can be chosen. On the one hand, this minimizes mood swings, and on the other, the cognitive difficulties make it difficult for many patients to remember to take their pills every day.

In general, there are hardly any contraindications to the combination of ADHD medications and hormone preparations; regular checks of vital signs and laboratory values are recommended for both preparations. During medication readjustment, particular attention should be paid to mood changes. In most cases, there is a clear stabilization of mood; rarely, in individual cases, an alternative preparation must be considered in the event of a mood slump, although this is more likely to be attributed to the progestins in combination preparations. Clinicians report that women with ADHD are more likely to have the more severe form of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDS), which involves depressed moods, hopelessness, affect lability, persistent anger, feelings of being overwhelmed, fatigue, and anxiety. During these phases, affected women find it particularly difficult to compensate for the symptoms. It is described that also in this case the use of estrogen preparations can relieve the suffering [30].

During pregnancy and while breastfeeding, ADHD medications are cautioned against to avoid harming the embryo. Here the study situation is meager. In a study of 3082 mothers, a total of eleven women were identified who had taken methylphenidate. No abnormalities were observed in any of their children. Only stimulant abuse (e.g., intravenous use of methylphenidate) has been shown to pose a risk for fetal malformations. Another study shows increased spontaneous abortion rate and partially decreased postnatal Apgar Index [41,42].

However, despite numerous contraceptive options, pregnancy can occur unnoticed, especially in ADHD patients, while the patient is still taking stimulants. The advice of specialists should be sought here, especially if drug therapy is to be continued in individual cases.

Summary

ADHD occurs with almost equal frequency in women and men. However, the symptoms may present differently or may not become apparent until puberty. In addition, differences are found in the development of comorbid diseases, so that women are sometimes diagnosed less frequently or only later. The diagnosis is made clinically according to ICD or DSM, additional questionnaires for women facilitate a gender-sensitive diagnosis. The female sex hormones have a decisive influence on the symptoms; in particular, fluctuations in hormone levels and an increased psychological reaction to this seem to play a role. It is important to inform the patients and their environment about this. If hormone replacement is desired, whether for contraception, menopause, or mood stabilization, preparations that result in consistent hormone levels (long-term preparations) should be considered and medication breaks should also be avoided with the “birth control pill.” During pregnancy, ADHD symptoms often subside so that medication can usually be dispensed with. A positive influence of hormones (naturally present or substituted) on ADHD symptomatology, but also on the effect of ADHD medication has been proven. Early sexual education, including about sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), contraception, and appropriate counseling services, is desirable. As a doctor, especially in women who try to present themselves adjusted and “normal”, but struggle with a wide variety of difficulties in life, report excessive reaction to hormonal fluctuations, or have children with an ADHD disorder, one should think about ADHD assessment and therapy.

Take-Home Messages

- Women are diagnosed less frequently and later with regard to ADHD, often reporting to the doctor with problems arising from a comorbid condition.

- Mothers with ADHD children should also be thought of for clarification due to the high genetic component.

- Due to risky sexual behavior, early and unwanted pregnancies as well as sexually transmitted diseases occur more frequently.

- Hormonal therapy, in addition to its actual indication (contraception, hormone deficiency), can also lead to a significant improvement in ADHD symptoms, as these are often exacerbated by hormonal fluctuations.

- ADHD can be treated well, and therapy should be multimodal whenever possible.

Literature:

- Thapar A, Cooper M: Attention deficit disorder. Lancet 2016; 387: 1240-1250.

- Fayyad J, Sampson NA, Hwang I, et al: The descriptive epidemiology of DSM -IV Adult ADHD in the World Health Organisation World Mental Health Surveys. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2017; 9: 47-56.

- Gaub M, Carlson CL: Gender differences in ADHD: a meta-analysis and critical review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997; 36: 1036-1045.

- Gershon J: A meta-analytic review of gender differences in ADHD. J Attent Disord. 2002; 5: 143-154

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. A, J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 716-723.

- Bruchmüller K1, Margraf J, et al: Is ADHD diagnosed in accordance with diagnostic criteria? Overdiagnosis and influence of client gender on diagnosis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012 Feb; 80(1): 128-138.

- Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, et al:. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 942-948.

- Faraone SV, Ghirardi L, Kuja-Halkola R, et al: The Familial Co-Aggregation of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Intellectual Disability: A Register-Based Family Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017; 56: 167-174.e1

- Pearson DA, Yaffee LS, Loveland KA, Lewis KR: Comparison of sustained and selective attention in children who have mental retardation with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Ment Retard 1996; 100: 592-607.

- Naerland T, Bakke KA, et al: Age and gender-related differences in emotional and behavioral problems and autistic features in children and adolescents with Down syndrome: a survey-based study of 674 individuals. J Intellect Disabil Res 2017; 61(6): 594-603.

- Young S, Absoud M, Blackburn C, et al: Guidelines for identification and treatment of individuals with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and associated fetal alcohol spectrum disorders based upon expert consensus. BMC Psychiatry 2016; 16: 324.

- Leyfer OT, Woodruff-Borden J, Klein-Tasman BP, et al: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in 4 to 16-year-olds with Williams syndrome. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychatr Genet 2006; 141B(6): 615-622.

- Landgren M, Svensson L, et al: Prenatal alcohol exposure and neurodevelopmental disorders in children adopted from eastern Europe. Pediatrics 2010; 125: 1178-1185.

- Niklasson L, Rasmussen P, Oskarsdottir S, Gillberg C: Autism, ADHD, mental retardation and behavior problems in 100 individuals with 22q11 deletion syndrome. Res Dev Disabil 2009; 30(4): 763-773.

- Pane M, Lombardo ME, Alfieri P, et al: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and cognitive function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: phenotype-genotype correlation. J Pediatr 2012; 161: 705-709.

- Sinzig J, Walter D, Doepfner M: Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: symptom or syndrome? J Atten Disord 2009; 13: 117-126.

- Xenitidis K, Paliokosta E, Rose E, et al: ADHD symptom presentation and trajectory in adults with borderline and mild intellectual disabilitiy. J Intellect Disabil Res 2010; 54: 668-677.

- Neece CL, Baker BL, et al: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children with and without intellectual disability: an examination across time. J Intellect Disabil Res 2011; 55: 623-635.

- Pearson DA, Lachar D, et al: Patterns of behavioral adjustment and maladjustment in mental retardation: comparison of children with and without ADHD. Am J Ment Retard 2000; 105: 236-251.

- Lambert NM, Hartsought CS, Sassone D, Sandoval J: Persistence of hyperactivity symptoms from childhood to adolescence and associated outcomes. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1987; 57: 22-32.

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Monuteaux MC, et al: Gender effects on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults, revised. Biol Psychiatry. 2004; 55: 692-700.

- Jensen CM, et al: Comorbid mental disorders in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a large nationwide study. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2015; 7: 27-38.

- Biederman J, Petty CR, et al: Adult psychiatric outcomes of girls with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: 11-year follow-up in a longitudinal case-control study. Am J Psychiat 2010c; 167: 409-417.

- Quin PO: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and its comorbidities in women and girls: an evolving picture. Curt Psychiatry Rep 2008; 10: 419-423.

- Ottonen, et al: Sex differentials in comorbidity Patterns of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J Child and Idol Psych 2018; Vol 58, Issue 4, 412-422.

- Sun S, Kuja-Halkola R, Faraone SV, et al: Association of Psychiatric Comorbidity With the Risk of Premature Death Among Children and Adults With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online August 07, 2019. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1944.

- Nadau K: Am I different? Girls and women with ADHD. Juvemus-Selbstverlag, Koblenz 2001.

- Krause J, Krause KH: ADHD in adulthood. Schattauer-Verlag, Stuttgart-New York 2005, 113.

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Seymour KE, et al: Efficacy of osmotic-release oral system, (OROS) methylphenidate for mothers with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): preliminary report of effects on ADHD symptoms and parenting. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69: 1938-1947.

- Solden S: “The Chaos Princess”, Munich, Forchheim: BH-AH 1999

- Ryffel-Rawak D: ADHD in women – at the mercy of emotions. Huber, Bern 2004, ISBN 3-456-84121-3.

- Walton E, Pingault JB, Cecil CA, et al: Epigenetic profiling of ADHD symptom trajectories: a prospective, methylome-wide study. Mol Psychiatry 2017; 22: 250-256.

- WURS, Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW: The Wender Utah rating scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150: 885-890.

- Brown TE. Brown Attention – Deficit Disorder Scales for Children and Adolescents (BrownADDScales). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp 2001.

- Christiansen H, Kis B, et al: German validation of the Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS) 2: Reliability, validity, diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. Eur Psychiatry 2011; 27: 321-328.

- Helgadóttir H, Gudmundsson ÓÓ, Baldursson G, et al: Electroencephalography as a clinical tool for diagnosing and monitoring attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e005500

- Sex Hormones and the Psyche: Fundamentals, Symptomatology, Diseases, Therapy, Herbert Kuhl, Georg Thieme Verlag 2002.

- Banaschewski T (guideline coordinator), Hohmann S, Millenet S, et al: Long version of the interdisciplinary evidence- and consensus-based (S3) guideline “Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood” 2018; AWMF register number 028-045. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/028-045l_S3_ADHS_2018-06.pdf Cortese S, Adamo

- N Del Giovane C, et al: Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2018.

- Arnett A, Stein M: Refining treatment choices for ADHD. Lancet Psychiatry 2018; 30295-30299.

- Pharmacovigilance and Embryonic Toxicology Advisory Center. Methylphenidate. www.embryotox.de/methylphenidat.html (accessed Oct 14, 2019)

- Bro SP, Kjaersgaard MI, Parner ET et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes after exposure to methylphenidate or atomoxetine during pregnancy. Clinical epidemiology 2015; 7: 139-147.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(12): xx-xx