Medication should always be combined with behavioral therapy. The most common mistake is underdosing nicotine replacement medication or using it for too short a time. The Reduce-to-Quit principle can strengthen the therapeutic relationship before definitive smoking cessation. The occurrence of withdrawal symptoms should be discussed from the beginning. Appropriate coping strategies must be developed.

Despite the known negative health effects in the population, according to the Addiction Monitoring Switzerland, 24.9% of all inhabitants are active smokers, and 35.1% are exposed to passive smoking for at least one hour per week [1–4]. Half of all smokers have the desire to become abstinent, but only 18% of them manage to give up smoking for more than 90 days. In view of the fact that on average only one third of all attempts at abstinence are accompanied by professional help, the need for better involvement of physicians in private practice arises [1–4]. Primary care physicians can play a key role in smoking cessation and abstinence assurance for their patients. On the one hand, he has regular contact with them, which benefits therapy motivation and monitoring. On the other hand, thanks to his central role, the general practitioner can best assess and advise the patient as a whole.

It is crucial to approach each smoker individually, as everyone has different arguments and strategies for quitting smoking (RS), which can be elicited in a so-called “motivational interviewing”. The primary care physician should then provide competent advice on behavioral and pharmacologic options for RS. Important are the therapeutic trusting relationship, the binding nature of the agreements on both sides and the regular follow-up contacts. Problems can thus be identified at an early stage and possible solutions discussed. Especially when taking prescription drugs, the effects and side effects should be monitored by a physician in order to make adjustments if necessary.

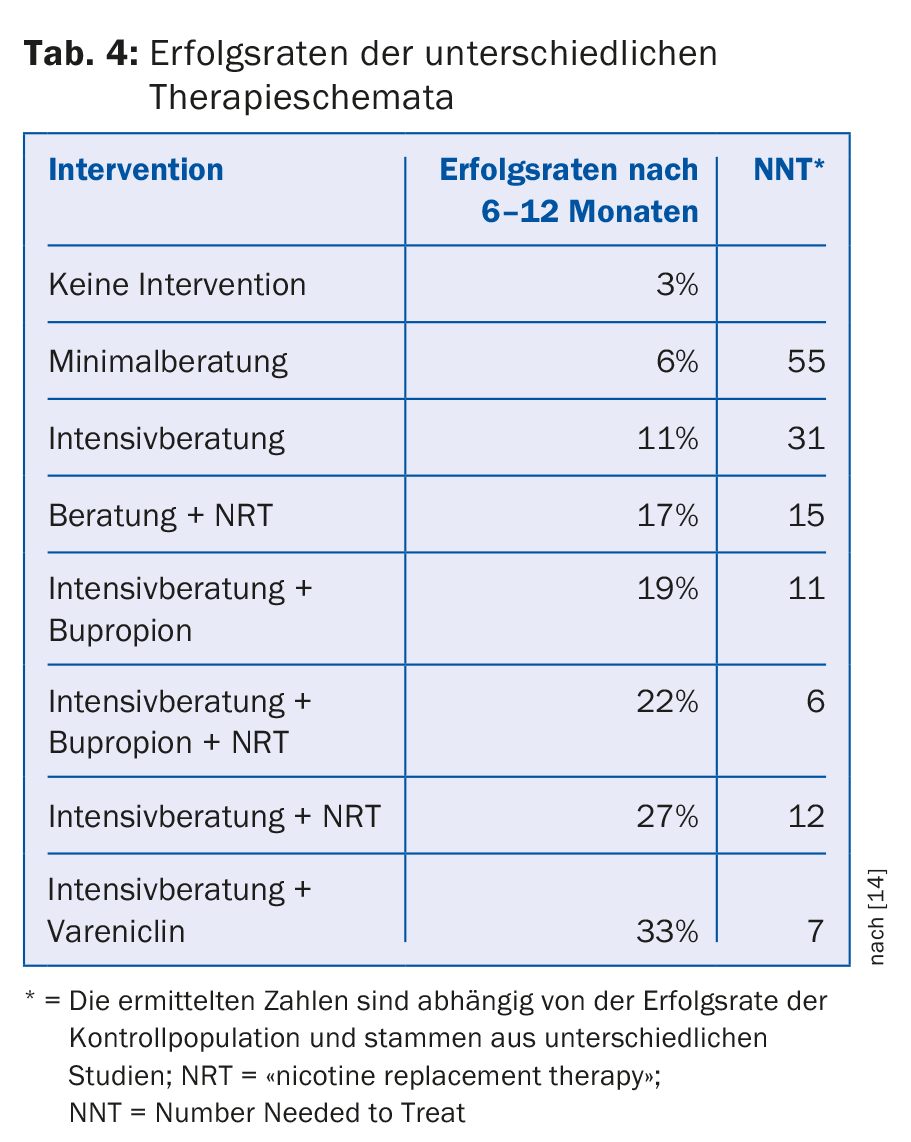

On average, it takes five to six serious RS attempts to reach prolonged RS. Therefore, the primary care physician should be knowledgeable about the likelihood of success of each RS strategy and learn motivational ways to deal with any setbacks. The inclusion of complementary medicine also interests many smokers who want to undertake an RS. It is therefore important to know which methods promise evidence-based success and which methods do not.

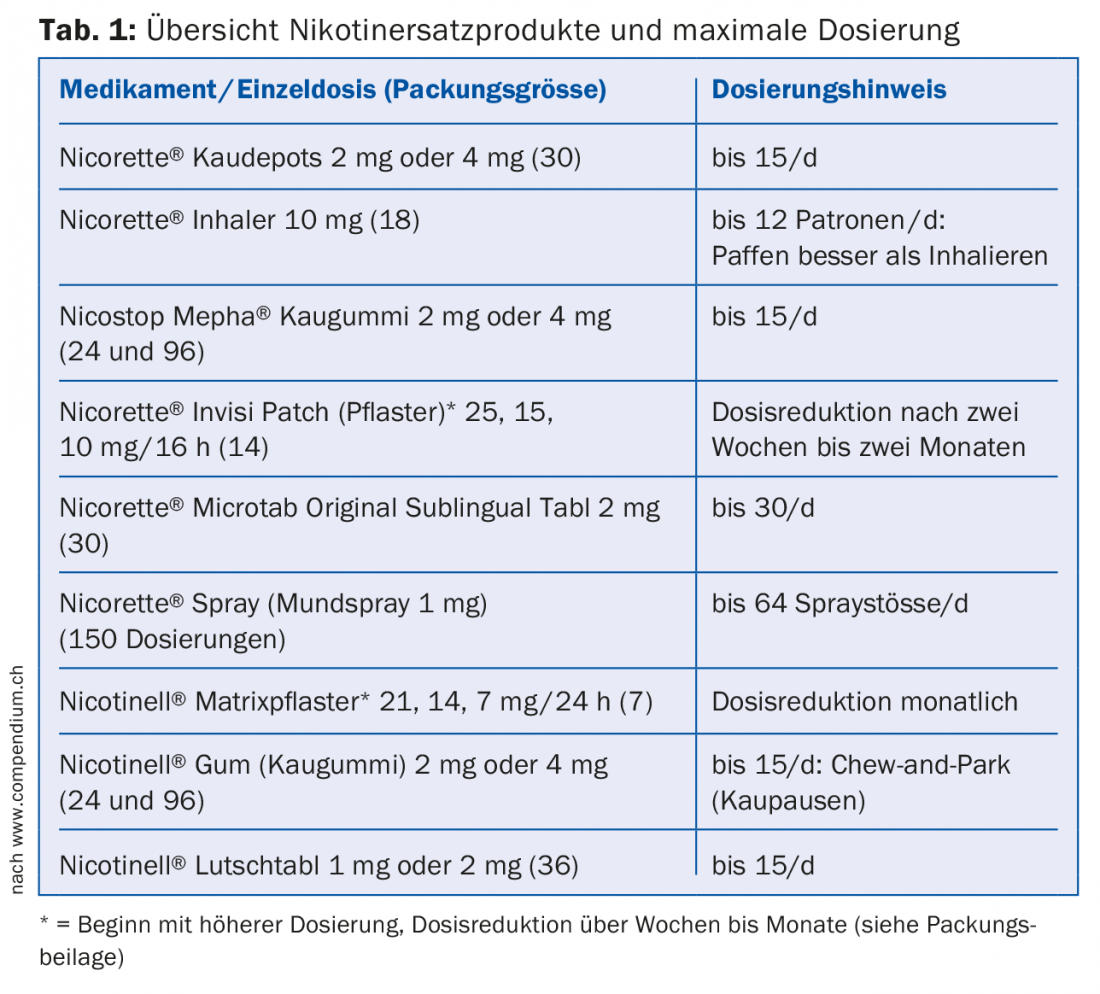

Nicotine replacement products

Nicotine replacement products (Nicorette®/Nicotinell®/Nicostop-Mepha®) have been used for RS for decades. They increase RS probability by up to 70% compared with placebo [5]. The majority are over-the-counter preparations that contain only pharmaceutical-grade nicotine and not the toxins found in cigarette smoke. Nicotine replacement products are given to prevent or attenuate nicotine withdrawal symptoms (Table 1). The most common mistake in nicotine replacement therapy is underdosing. Therefore, only the maximum daily dosages are given in Table 1 as a guide. There is now a broad market for these products and various dosage forms are offered. It should be emphasized that their combination is more effective than therapy with a single drug [5], and that the effective dose may vary considerably for different smokers individually.

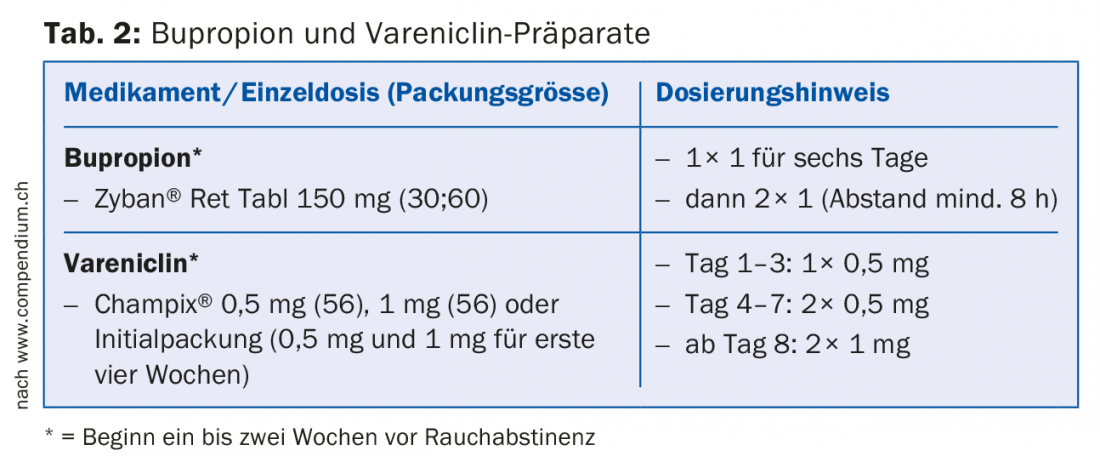

Bupropion and varenicline

Both bupropion and varenicline are nicotine-free prescription medications (Table 2) that can provide substantial support to RS in the early weeks and months [6]. It is important to know the contraindications and precautions for both preparations in order to choose the best therapy individually for each patient. Bupropion can counteract the often therapy-limiting weight gain in RS, varenicline shows the best longer-term smoking abstinence rate [6,7].

In the past, reports of increased suicidality and cardiovascular events with varenicline use attracted considerable media interest. However, retrospective studies have been able to put these concerns into perspective and should be communicated to primary care physicians and patients to avoid any reservations about this effective drug [8]. It is sometimes helpful in this context to address the potential side effects of continued cigarette use or to study together the many harmful constituents in tobacco smoke.

Secondline Pharmacotherapy

For completeness, it should be mentioned here that there is evidence for clonidine and nortriptyline as second-line drugs [9,10]. However, the sometimes disproportionately high rates of side effects make these agents take a back seat in RS support. Neither drug is approved for this indication in Switzerland.

Alternatives

Regardless of the RS strategy chosen, combining it with behavioral therapy increases its chances of success. In general, this should aim to identify trigger factors for smoking and develop appropriate coping strategies that allow the smoker to ignore the stimulus.

In many cases, patients also wish to receive non-drug or complementary medicine therapy. Unfortunately, the evidence base regarding these therapies is qualitatively or quantitatively insufficient to make an evidence-based recommendation for these methods. Acupuncture, hypnosis and the book “Finally Non-Smoker” should therefore not be recommended in the first place. If patients are successful with this, medical support for long-term abstinence is certainly recommended.

For smokers without a firm will to quit or those who have repeatedly failed in quit attempts, the possibility of smoking reduction (reduce-to-quit principle) should be considered. In the long term, this hardly improves the consequences of the health impairment. However, due to the existing relationship between the indecisive or unsuccessful patient and the consulting physician, it can be a temporary step on the way to definitive smoking cessation and sometimes boosts confidence for the upcoming behavior change [11].

E-cigarettes

The Swiss Society of Pneumology and the American Heart Association oppose e-cigarettes as a first measure for RS. There are already well-studied nicotine replacement products and other medications with proven efficacy. E-cigarettes are no more successful than existing drugs. There are no long-term data yet on the health effects of aerosol inhalation of components, some of which are harmful to health and addictive [12].

Vaccinations

Antibodies can block the diffusion of nicotine across the blood-brain barrier and/or binding to specific CNS centers. This mechanism was used in initial studies to evaluate possibilities for vaccination against nicotine dependence [13]. However, the data in this area is still inconsistent and further studies need to evaluate the efficacy and side effect profile of this technique.

Smoke status verification

In case of questionable smoking abstinence, the easy to determine measurement of the CO level in exhaled air or of the nicotine metabolite cotinine in urine, saliva or serum is useful.

Withdrawal symptoms and chances of success

The undesirable symptoms of nicotine withdrawal often begin a few hours after RS and usually reach their maximum within a week. To reduce these symptoms resp. distract yourself from it, you can make some general recommendations. The person intending to RS should try to change habits that he or she associates with smoking (e.g., drinking less coffee if it was otherwise always accompanied by a cigarette). In practice, it has proven effective for patients to routinely perform three activities to distract themselves from the desire to smoke. These should be simple and feasible in everyday life at any time, for example

- drink a glass of water

- take a sugar free lozenge

- Perform a physical activity such as climbing stairs.

Often, these activities already reduce the craving for the cigarette. If it occurs again later, the routine should be run again.

Sometimes, however, even these measures are insufficient and people still resort to cigarettes. However, even the reduction in the number of cigarettes consumed per day should be considered an intermediate success and should show the patient that he is capable of changing his behavior. In everyday life, it has proven useful to write these distraction activities on a piece of paper in a clearly visible place, e.g. on the refrigerator or computer screen.

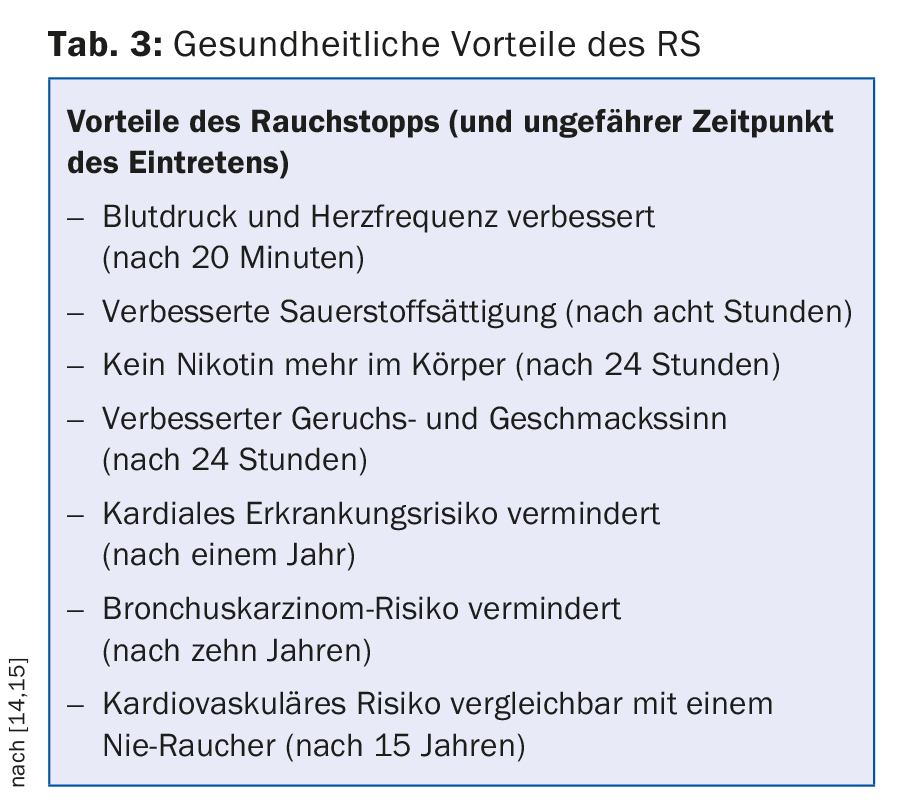

Many smokers find it rewarding to realize the health benefits of RS after only a short time (table 3).

Constipation, which is common, can be addressed by drinking more fluids and adding more fiber to the diet. Weight gain, fatigue, headaches and increased irritability can be countered with nutritional counseling, relaxation exercises and exercise. The burden of such symptoms should not be underestimated and underscores the importance of consistent care in the primary care setting during this period. The multilingual stop-smoking line (0848 000 181) and the SmokeFree Buddy app can provide support.

Conclusion

In summary, medication support combined with intensive medical counseling achieves the best long-term abstinence rates in RS (Tab.4). It is important to provide adequate support to any patient seeking RS, as the chance of success of the so-called “spontaneous quit attempt”, i.e. RS without professional support and medication, is very poor. Complementary behavioral therapy is useful to develop the necessary strategies and avoid relapse-prone situations in the long run. Withdrawal symptoms should always be factored in and treated as early as possible.

From a health and economic perspective, RS is one of the most important approaches in primary and secondary prevention of the primary care patient population.

Acknowledgments: We thank Dr. Alice Zürcher for reviewing the manuscript.

Literature:

- Continuous Rolling Survey on Addictive Behaviors and Related Risks (CoRolAR). 2011-2014.

- Gmel G, et al: Suchtmonitoring Schweiz – Konsum von Alkohol, Tabak und illegalen Drogen in der Schweiz im Jahr 2014. Sucht Schweiz: Lausanne, Switzerland 2015.

- Swiss Health Survey (SGB) for the Swiss population as a whole. 1992, 1997, 2002, 2007, 2012.

- Kuendig H, Notari L, Gmel G: Le tabagisme passif en Suisse en 2013. Analyse des données du Monitorage suisse des addictions. Addiction Suisse: Lausanne 2014..

- Stead LF, et al: Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012; 11: CD000146.

- Gonzales D, et al: Varenicline, an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006 Jul 5; 296(1): 47-55.

- Gadde KM, et al: Bupropion for weight loss: an investigation of efficacy and tolerability in overweight and obese women. Obes Res 2001 Sep; 9(9): 544-551.

- Kotz D, et al: Cardiovascular and neuropsychiatric risks of varenicline: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2015 Oct; 3(10): 761-768.

- Gourlay SG, et al: Clonidine for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004; (3): CD000058.

- Hughes JR, et al: Nortriptyline for smoking cessation: a review. Nicotine Tob Res 2005 Aug; 7(4): 491-499.

- Schuurmans MM, Zellweger JP: Smoking cessation in the physician’s office – new possibilities? Rev Med Suisse 2012; 8: 235-236.

- Schuurmans MM, Barben J: Statement on e-cigarettes. Swiss Medical Journal 2014; 95(16/17): 645-646.

- Hartmann-Boyce J, et al: Nicotine vaccines for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 Aug 15; 8: CD007072.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General 2004.

- Hughes JR: Effects of abstinence from tobacco: valid symptoms and time course. Nicotine Tob Res 2007 Mar; 9(3): 315-327.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(7): 16-20