The Multiple Sclerosis Symposium at Inselspital in Bern provided a broad overview of the epidemiology, etiology, course, assessment, and current pharmacotherapy of the condition. There are exciting findings from basic research that has identified the cytokine GM-CSF as a potential new therapeutic target. The MS disability survey is currently examining electronic tools that could help standardize in the future. Pharmacotherapy remains a broad field – the side effect profile is the main factor in decision-making.

Christian Kamm, MD, University Department of Neurology, Inselspital Bern, gave a brief introduction to the epidemiology of multiple sclerosis (MS). MS is a chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system (autoimmune disease). It usually consists of an initial phase with inflammatory reactions leading to relapses. Then, usually after 15-20 years, the second secondary progressive, degenerative phase follows (partly still superimposed by relapses).

On average, affected individuals are about 30 years old (incidence peak between 20 and 40 years). The prevalence is 83:100,000 in Europe – it has increased in recent years due to increased life expectancy of MS patients and advances in diagnosis. Women are usually affected somewhat earlier (two to five years) and also more frequently. “The exact etiology remains unclear, but environmental and genetic factors play a key role,” he said. Environmental influences are sometimes reflected in the different distribution of the disease according to latitude: the risk of MS decreases with increasing proximity to the equator, which is sometimes explained by vitamin D metabolism [1]. The effect of vitamin D substitution remains unclear, but is currently being investigated in several studies (the SOLAR study will be completed soon).

Vascular comorbidities (smoking, etc.) also significantly worsen the course. Increasingly, their number is associated with an increased risk of disability progression, of moving to the secondary progressive phase, and of disease progression and severity in general. In addition, infections play a role. A well-known trigger for MS is the Epstein-Barr virus. Children and adolescents are particularly at risk from environmental risk factors. Those who develop glandular fever late in adolescence have a higher risk of MS.

The genetic component is sometimes reflected in the fact that a patient’s relatives are more likely to develop the disease compared with the general population (the relative risk in first-degree relatives is approximately 9.2). There are correlations to the so-called Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA). Population studies have also shown that disease incidence differs even among ethnicities exposed to comparable environmental factors.

GM-CSF as a new therapeutic target?

Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Burkhard Becher, Institute of Experimental Immunology, University of Zurich, addressed the role of the pro-inflammatory cytokine GM-CSF, among others. This is essential for the development of MS in mice. To elucidate the role of GM-CSF in the pathogenesis of human MS, blood from MS patients or healthy donors was analyzed, white blood cells were isolated, and cytokines produced were analyzed. The studies illustrate that the number of GM-CSF-producing T cells is greatly increased in MS patients. And, the more severe the disease activity, the more cells make GM-CSF. This is induced by interleukin 2 (IL-2), which in turn makes the receptor of IL-2 an MS risk gene. Thus, healthy donors with this risk gene (polymorphism in the IL-2 receptor-α gene) have been shown to have more GM-CSF-producing T cells than donors with the non-risk gene [2]. But how can this finding be translated into the clinic? “For example, with an antibody against GM-CSF such as MOR103 [3],” Prof. Becher explained. “The future will tell if we are looking at a new candidate for MS therapy.”

Disabilities in MS – how to measure?

Disabilities in MS were the topic of the presentation by Christian Kamm, MD, University Department of Neurology, Inselspital Bern. So-called “no evidence of disease activity” (NEDA) is currently defined by three parameters: absence of relapses, absence of EDSS progression, absence of MRI activity. The integration of the factors “brain atrophy” and “cognition” into this concept is sometimes discussed. The Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) remains the gold standard for measuring disability in MS (electronically standardized at neurostatus.net). In seven functional systems (visual, brainstem, pyramidal, cerebellum, sensorium, bowel/bladder, mental function) the severity of disability is assessed. In addition, there is information on walking ability. The scale starts at 0 and goes up to 10. Weaknesses of the EDSS are: Variability in the neurological examination, in the perception of the examiner, and natural limitations of human perception. Currently, digital assessment tools (e.g., with the Kinect® camera) are being tested, which could be used to assess motor functions in MS in a more accurate and standardized way in the future (ASSESS-MS-Project).

Above a value of 4.5, the EDSS takes into account almost only the walking distance and thus has certain limitations that can be remedied by additional tests. For example, upper extremity function should be tested separately because it is increasingly limited in advanced EDSS. The so-called Nine-Hole Peg Test (9HPT) tests how long it takes the patient to place nine pegs in designated holes and then remove them again. According to the speaker, this test is reliable, valid and sufficiently sensitive to assess manual dexterity in MS patients. Norm data exist according to age, gender, and right- or left-handedness [4]. While the 9HPT still requires various utensils, the Coin Rotation Task (CRT) developed in Bern only requires a 50-centime coin. Here, patients must rotate the coin between the thumb, index finger, and middle finger as quickly as possible (over 19 s for 20 half-reversals is pathological) [5]. “The CRT is comparable vailde as the 9HPT and the so-called Action Research Arm Test (ARAT), but not equally feasible above an EDSS of about 7,” Dr. Kamm explained.

Cognition is also underrepresented in the EDSS, although such impairments as memory, attention or concentration deficits are among the main symptoms of MS (prevalence 43-65%). The Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) can be considered as a practical supplement [6].

State of pharmacotherapy

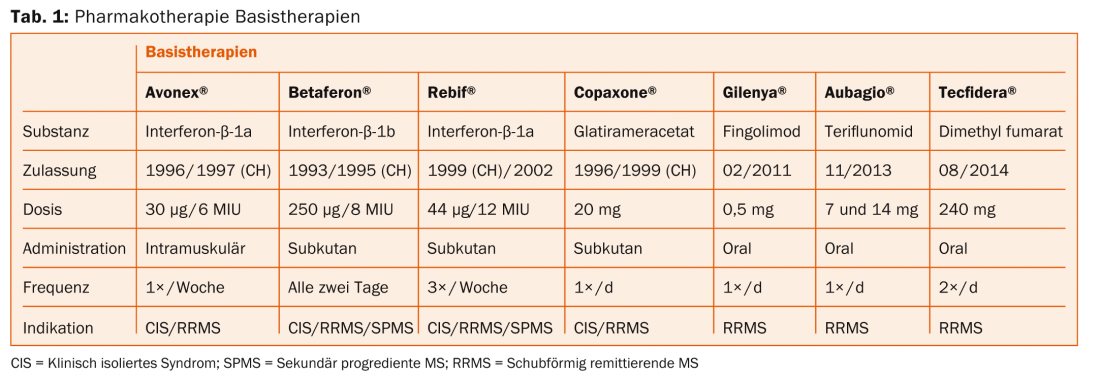

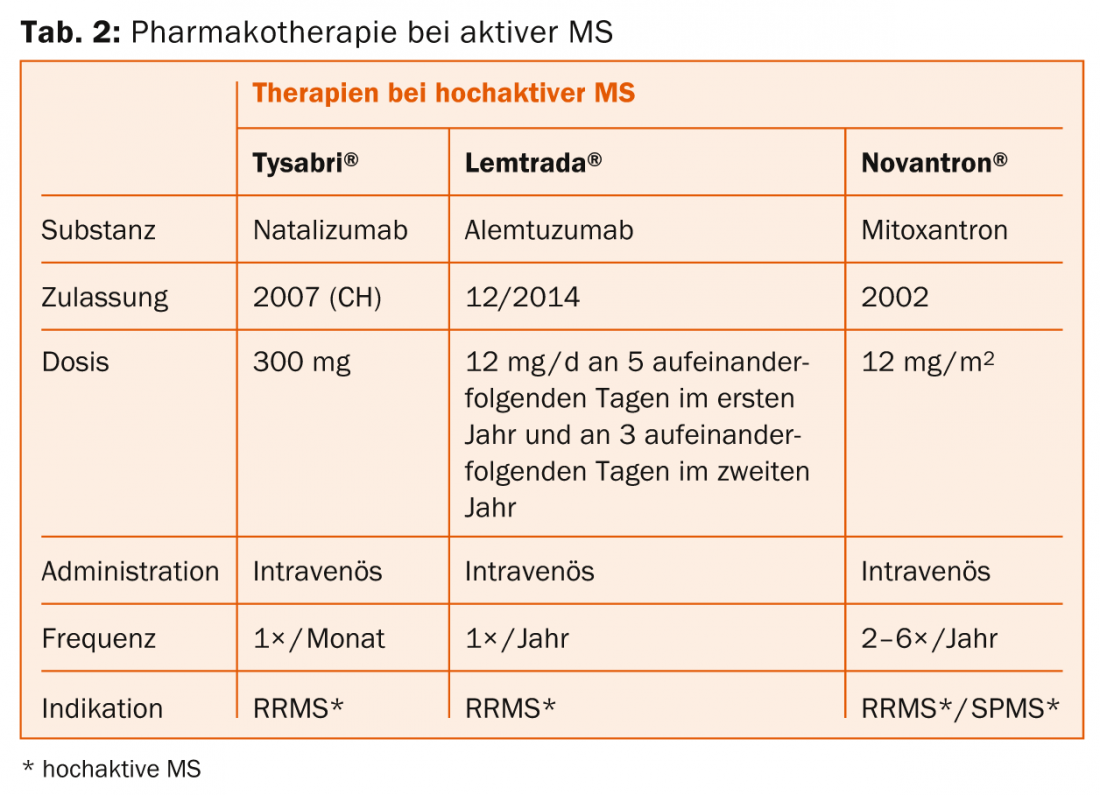

An overview of MS therapeutics is provided in tables 1 and 2. According to Prof. Heinrich Mattle, MD, University Department of Neurology, Inselspital Bern, randomized controlled trials show that MR lesions are the main driver of neurological deficits – so they must be prevented therapeutically. In relapsing-remitting MS, lesions are initially found mainly in the white matter, and in the secondary progressive form, increasingly also in the gray matter [7]. This is then crucial for long-term disability, as Prof. Nicola De Stefano, MD, University of Siena, clarified in his previous lecture [8].

“Therapy should thus take place as early as possible to improve long-term outcome. But the principle of “Primum nihil nocere” (“First do no harm”) also applies, i.e. finding the optimal balance between effect and side effects,” Prof. Mattle explained.

Injectable drugs (Betaferon®, Rebif®, Avonex®, Copaxone®): Need regular injection. Possible side effects are skin or systemic reactions. However, there are no serious long-term side effects. “We do not yet know the effects of the new drugs after 20 years. This is where the injectable agents are best researched,” Prof. Mattle emphasized. In the near future, pegylated β-interferon (peginterferon-β-1a) will also enter the Swiss market (ADVANCE study [9]), which needs to be injected less frequently than the other agents.

Fingolimod (Gilenya®): Administration is oral, once daily. The drug may cause cardiac side effects (monitoring required at first administration). Macular edema and herpes virus infections are also possible but rare. The drug is contraindicated during pregnancy. For patients at risk for malignant skin tumors, caution or regular dermatologic monitoring is advised to be on the safe side (although concerns in this regard are not clearly established).

Teriflunomide (Aubagio®): Administration is oral, once daily. Bi-weekly monitoring of liver enzymes is required in the first six months, after which eight-week monitoring is sufficient. Possible side effects include nausea, diarrhea, and alopecia. A reliable contraceptive method is a prerequisite for therapy.

Dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera®): The active ingredient is administered orally twice daily (which may limit adherence). Blood work is due before treatment begins, after three months and six months, and then every six to twelve months. Possible side effects include flushing, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Here, too, contraception is a prerequisite.

Natalizumab (Tysabri®): The active ingredient is conveniently administered by infusion once a month. A weighty risk is progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) in patients with JC virus, so antibody detection is necessary.

Alemtuzumab (Lemtrada®): The active ingredient is conveniently administered twice in two years by infusion series. Serious infusion reactions may occur. Also of note is the risk of developing other autoimmune diseases (including thyroid or kidney) or immune thrombocytopenia.

Application in practice

At the time of the event (January 2015), Bern had the following treatment regimen for relapsing-remitting MS:

First-line: depending on side effects and disease activity, interferon-β, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, or fingolimod is used. In highly active MS, natalizumab and alemtuzumab may be considered.

Second line: If activity exists, a choice is made between dimethyl fumarate, fingolimod, natalizumab or alemtuzumab (or mitoxantrone if necessary).

Third line: Natalizumab and alemtuzumab (possibly also mitoxantrone) are initially available here. Drugs not approved in Switzerland for this indication, such as rituximab or daclizumab, or autologous stem cell transplantation, are experimental procedures (also for highly active forms).

For secondary progressive MS, in contrast to the primary degenerative form, there are more data, but overall the research situation is worse than for relapsing-remitting MS. Rebif® has been shown to be more effective against secondary progressive MS in those patients still experiencing clinical relapses [10]. Betaferon® also benefits patients with relapse activity and clearly present disability progression (EDSS change >1, two years prior to study entry) the most [11].

For symptomatic therapy, Sativex® may be considered. It is used for symptom improvement in patients with moderate to severe spasticity.

Source: Multiple Sclerosis Symposium, January 8, 2015, Bern

Literature:

- Ascherio A, et al: Vitamin D as an early predictor of multiple sclerosis activity and progression. JAMA Neurol 2014 Mar; 71(3): 306-314.

- Hartmann FJ, et al: Multiple sclerosis-associated IL2RA polymorphism controls GM-CSF production in human TH cells. Nat Commun 2014 Oct 3; 5: 5056. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6056.

- Korolkiewicz RP, et al: Phase Ib Study to Evaluate MOR103 in Multiple Sclerosis. NCT01517282. Online at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT01517282.

- Oxford Grice K, et al: Adult norms for a commercially available Nine Hole Peg Test for finger dexterity. Am J Occup Ther 2003 Sep-Oct; 57(5): 570-573.

- Heldner MR, et al: Coin rotation task: a valid test for manual dexterity in multiple sclerosis. Phys Ther 2014 Nov; 94(11): 1644-1651.

- Van Schependom J, et al: The Symbol Digit Modalities Test as sentinel test for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2014 Sep; 21(9): 1219-1225, e71-72.

- Kutzelnigg A, et al: Cortical demyelination and diffuse white matter injury in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2005 Nov; 128(Pt 11): 2705-2712.

- Filippi M, et al: Gray matter damage predicts the accumulation of disability 13 years later in MS. Neurology 2013 Nov 12; 81(20): 1759-1767.

- Calabresi PA, et al: Pegylated interferon β-1a for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (ADVANCE): a randomised, phase 3, double-blind study. Lancet Neurol 2014 Jul; 13(7): 657-665.

- Secondary Progressive Efficacy Clinical Trial of Recombinant Interferon-Beta-1a in MS (SPECTRIMS) Study Group: Randomized controlled trial of interferon- beta-1a in secondary progressive MS: Clinical results. Neurology 2001 Jun 12; 56(11): 1496-1504.

- Kappos L, et al: Interferon beta-1b in secondary progressive MS: a combined analysis of the two trials. Neurology 2004 Nov 23; 63(10): 1779-1787.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(2): 36-39.