Endometrial carcinoma, uterine sarcomas, cervical carcinoma – uterine tumors are as diverse as the different cells found in the uterus. Accordingly, the management also differs significantly. Careful diagnostics for classification and risk classification is crucial to provide the best possible care on an individual basis.

Uterine tumors affect women of different ages and at different stages of life. The origin of tumors is varied, as are the different cells found in the uterus. Malignant processes often present themselves in the common symptomatology of vaginal bleeding.

In this review article, we would like to discuss the various uterine tumors and provide an overview with an outlook on therapeutic options.

Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial carcinoma is one of the most common gynecologic tumors after breast carcinoma with registration of 4634 cases in the na-tio-nal cancer registry of Switzerland in 2013-2017. In just over 75% of cases, endometrial cancer is diagnosed in postmenopause, after frequent postmenopausal bleeding. Excess estrogen is considered a risk factor in hormone-dependent endometrial carcinoma (type I). This is evidenced by the increased risk associated with estrogen therapy alone in postmenopause (tibolone, tamoxifen, depending on the duration of use, also combined therapy with progestin, ovarian stimulation therapies) [1]. Early menarche and late menopause can also promote endometrial cancer, as can obesity, impaired glucose metabolism, and the presence of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). A positive family history of occurrence of endometrial cancer in 1st-degree relatives has an increased risk of 3.5% of developing the disease by age 70 years compared with the normal population of 3.1% [2]. Fortunately, endometrial cancer is often symptomatic in the early stages in terms of postmenopausal bleeding, which explains to some extent the good prognosis with a 5-year survival probability of 80%. In premenopausal patients with abnormal uterine bleeding, the risk of hyperplasia with atypia or carcinoma is less than 1.5%. However, after an unsuccessful attempt at conservative therapy, a biopsy by pipelle or hysteroscopy and curettage for histological examination should be performed generously.

The gold standard of diagnosis remains hysteroscopy with curettage, which should be performed in cases of postmenopausal bleeding with an endometrium ≥3 mm. Local uterine conditions should be assessed by transvaginal sonography. If the findings are unclear, an MRI scan of the pelvis can provide clarity. Further imaging by computed tomography is indicated in advanced stages or aggressive histology to assess extrauterine conditions.

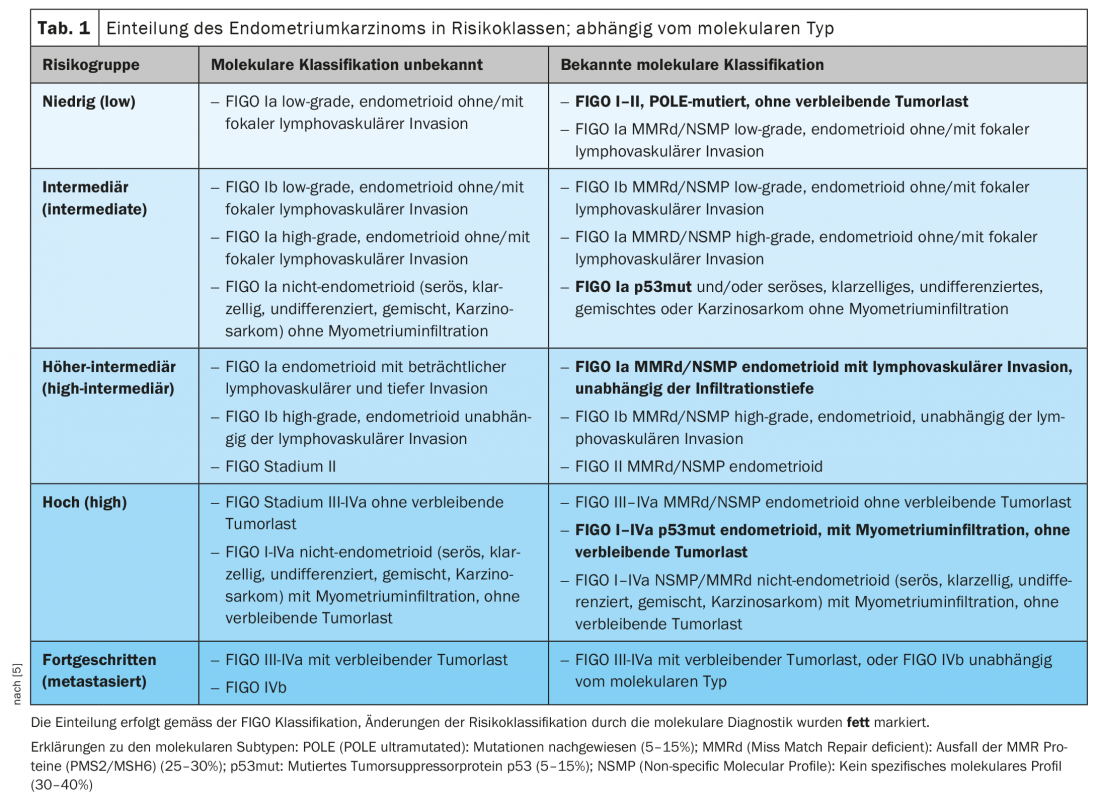

Endometrial cancer is classically divided into two types. Type I, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, is hormone sensitive, while type II carcinoma is hormone independent. The type II carcinoma group is composed of more aggressive serous or clear cell carcinomas and carcinosarcomas and affects an older population. Molecular analysis by the TCGA group (The Cancer Genome Atlas-Project) has allowed endometrial cancer to be divided into four molecular groups, which may provide better predictive power of prognosis and adapted therapy in the future. In the WHO Pathology 2020 edition, endometrial cancers are now classified as POLE, MMRd (mismatch repair deficient), p53mut, and NSMP (non-specific molecular profile). The prognosis is very favorable in the POLE mutant, followed by the microsatellite unstable type MMRd; p53mut carcinomas have a significantly worse prognosis and behave similarly to ovarian serous carcinoma [3,4].

The ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO risk classification has integrated molecular markers in your latest 2021 edition, so these markers are now included in the clinic (Table 1) [5]. In advanced tumors, molecular markers, particularly MMRd, enable newer therapeutic options using checkpoint inhibitors.

Nowadays, surgical therapy should be performed by means of laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy. In premenopausal patients, the adnexa can be left in early stages, after risk education and if there is no BRCA mutation and no Lynch syndrome. Staging is performed surgically. This may include a frozen section to evaluate infiltration thickness. The decision whether to perform pelvic and para-aortic lymphonodectomy and omentectomy depends on the risk group (intermediate-high and high-risk) and stage (pT1b, G3, type II, L1). Lymphonodectomy should always include pelvic and para-aortic lymphonodectomy according to the uterine lymphatic drainage. Macroscopically conspicuous lymph nodes should also be removed in early-stage type I carcinomas.

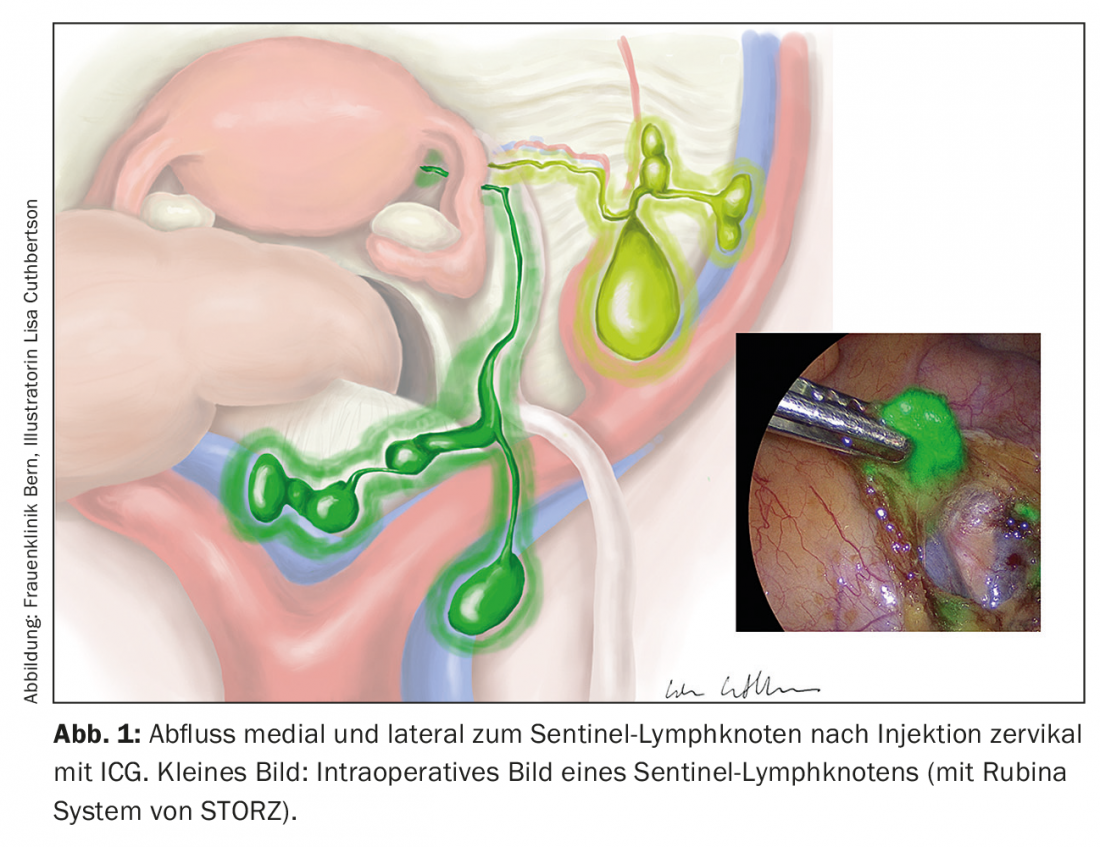

The concept of sentinel lymph node excision has now been investigated in many studies. Indocianin green is applied cervically or peritumorally and can be visualized intraoperatively using a near-infrared imaging technique (Fig. 1). The technique does not increase morbidity and the detection rate is over 90%, with a false positive rate of 5%. Ultrastaging by immunohistochemical examination of negative sentinel lymph nodes may have additional benefit by visualizing micrometastases [6–8]. However, in high-risk situations, sentinel lymph node excision remains indicated only in the context of trials.

Fertility-preserving therapy is only considered in stage IA after exclusion of myometrial infiltration. After explicit information, a progestogen therapy (minipill or progestogen IUD) is carried out for six months, followed by the desire to have a child. Once this is met, surgical staging should be performed.

Uterine sarcomas

Sarcomas are found much less frequently than endometrial carcinomas, with an incidence of 1.5-3/100 000, with significantly increased mortality. The 5-year survival rate is less than 50%. Sarcomas may originate in the myometrium, uterine connective tissue, or endometrial stroma. The WHO distinguishes between leiomyosarcoma (60-70%), low- or high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (10% each), undifferentiated uterine sarcoma (10%), adenosarcoma, and the malignant variant of PEComa ( perivascular epithelioid cell tumor ) (both significantly less common). Risk factors include African ancestry, tamoxifen use, and a germline mutation in the TP53 gene, also called Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

Clinically, sarcomas often present with vaginal bleeding, but a rapidly growing uterus may also indicate the presence of a sarcoma. Hysteroscopy, as well as more advanced imaging procedures such as an MRI scan, can provide evidence of sarcoma but cannot rule it out. Sarcomas are often found as incidental findings during myomectomies or hysterectomies, which carry the risk of malignant cell distribution and thus worsen the prognosis. Informing patients before every operation is standard nowadays. If clinically suspected, the surgical technique should be adjusted accordingly.

Therapy for leiomyosarcoma includes total hysterectomy. Adnexectomy and systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphonodectomy are not primarily indicated in the presence of low incidence of metastases in this area, unless intraoperative abnormalities are evident [9]. Sufficient evidence for adjuvant therapy after R0 resection is still lacking. Adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin or a combination of gemcitabine and docetaxel are individual options without clear recommendations. Adjuvant radiotherapy should be discussed in cases of incomplete surgical resection. In primary metastatic situations, doxorubicin is used. Aromatase inhibitor administration may prolong progression-free survival after confirmation of hormone receptor expression.

In low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma, the prognosis is good with a 5-year survival rate of 80-90%. If hormone receptor status is positive, this can be improved by bilateral adnexectomy or adjuvant endocrine therapy from stage III.

High-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma and undifferentiated uterine sarcomas have an infauste prognosis with a median overall survival of 1-3 years. Clear therapy recommendation is for total hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy. Percutaneous radiotherapy is recommended in stage I and II. Adequate data on chemotherapy or endocrine therapy are not available.

Cervical Cancer

In Switzerland, there are about 250 new cases of cervical carcinoma each year. Through screening and, in the future, HPV vaccination, we expect a further decrease in these numbers. Unfortunately, cervical cancer still accounts for about 1% of all cancer deaths. Tumor stage by FIGO at diagnosis has a major impact on 5-year overall survival. This is 21% in stage IV and 95% in stage I. Risk factors include persistence of high-risk HPV infection with possible cervical dysplasia, as well as immunosuppression, nicotine abuse, poor sexual hygiene, changing sexual partners, and long-term use of oral contraceptives. Clinically, this neoplasia is also often manifested by typical (post-coital) bleeding or altered vaginal fluorine.

HPV-dependent squamous cell carcinoma accounts for up to 80% of cervical cancer cases. The remaining 20% are largely composed of adenosquamous carcinomas and adenocarcinomas. Less common histologic subtypes include mixed, neuroendocrine, serous, papillary, and clear cell carcinomas.

The diagnosis is made after an abnormal Pap smear by histological confirmation in the form of a portio biopsy or endocervical curettage. Local conditions can be assessed by transvaginal ultrasonography, renal ultrasonography to exclude hydronephrosis, and MRI or anesthetic examination by cystoscopy and/or rectoscopy. PET-CT is used in primary suspected distant metastases or in recurrence situations. Primary clinical staging in cervical cancer was supplemented in 2018 by a combination of imaging and lymph node involvement in the updated FIGO classification [10]. Paraaortic lymph node involvement cannot be diagnosed with sufficient sensitivity by PET-CT, and therefore nodal status should be determined primarily surgically by sentinel lymphonodectomy, which has a sensitivity of 91.4% with a specificity of 100%. Sentinel lymphonodectomy is not necessary for tumor stage T1a1 without lymphovascular invasion, complete excision by conization, and microinvasive carcinoma. In some circumstances, a simple conization or hysterectomy may be sufficient in these cases.

Surgery or radiochemotherapy may be considered as primary therapy. Up to tumor stage FIGO IIA, primary surgical resection by open radical hysterectomy is recommended. The indication for ovariectomy is based on histologic type and menopausal status.

The prospective, randomized LACC trial published in 2018 compared outcomes after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy with those after laparotomy. Tumor size ≥2 cm showed poorer outcome in terms of recurrence-free interval, higher rate of locoregional recurrence, and also significantly lower overall survival compared with open radical hysterectomy. Whether tumor cells are dispersed by the uterine manipulator used during laparoscopy or byCO2 inflation was not clarified by this study [11].

Starting at stage IIB or with proven lymph node fall after performed paraaortic lymphonodectomy, radiochemotherapy is the standard of care. Percutaneous radiotherapy with simultaneous administration of cisplatin-containing chemotherapy as a radiosensitizer is performed before intravaginal brachytherapy. Studies of secondary hysterectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy showed no benefit.

In selected cases, adjuvant radiotherapy with chemotherapy is recommended after primary surgical treatment. This applies to R1 resections, parametrial infiltrations, lymph node metastases, and risk factors (L1, V1, G3, tumor size >4 cm). The indication for vaginal brachytherapy should be discussed in cases of vaginal infiltration, large tumors, and extensive L1. Palliative therapy primarily involves chemotherapy with carboplatin and taxol combined with bevacizumab. Checkpoint inhibitors can also be used here.

Conclusion

In summary, uterine tumors include quite different entities and are treated differently accordingly. Accurate diagnosis for classification is critical. Molecular markers are increasingly important, both for risk classification and for tailoring adjuvant therapies.

Take-Home Messages

- Uterine tumors comprise diverse entities whose management differs significantly. Careful diagnostics for classification and risk classification are crucial in order to provide the best possible care on an individual basis.

- The clinical importance of molecular markers is increasing; as of this year, these are part of the ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO risk classification of endometrial cancer. Molecular markers, in addition to providing a more accurate prognosis assessment, also enable the targeted use of innovative treatment options such as checkpoint inhibitors, especially in advanced tumors.

- Endometrial carcinoma is one of the most common gynecologic malignancies, with 75% diagnosed in postmenopause. It is usually manifested by vaginal bleeding and is favored by excess estrogen, including with tamoxifen therapy. In any case of postmenopausal bleeding and an endometrium ≥3 mm, pipelle or hysteroscopy with curettage should be performed for histological confirmation.

- Uterine sarcomas, although less common than endometrial carcinomas, are associated with a poorer prognosis. Tamoxifen use is also one of the risk factors here. Myomectomies and hysterectomies carry the risk of malignant cell distribution, so surgical technique should be adjusted accordingly in cases of clinical suspicion.

- The prognosis for cervical cancer varies greatly depending on the tumor stage.

- In early stages up to FIGO IIA, open radical hysterectomy with or without ovariectomy is the first-line therapy. Radiochemotherapy is primarily used from stage IIB or when lymph node involvement is proven. Hysterectomy performed secondarily does not confer any benefit.

Literature:

- Allen NE, et al: Menopausal hormone therapy and risk of endometrial carcinoma among postmenopausal women in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition. Am J Epidemiol. 2010; 172(12): 1394-1403.

- Win AK, Reece JC, Ryan S: Family history and risk of endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 125(1): 89-98.

- Kandoth C, et al: Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature, 2013; 502(7471): 333-339.

- Morice P, et al: Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2016 ; 387(10023): 1094-1108.

- Concin N, et al: ESGO / ESTRO / ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2021; 478(2): 153-190.

- Rossi EC, et al: A comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy to lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer staging (FIRES trial): a multicentre, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2017; 18(3): 384-92.

- Papadia A, et al: Laparoscopic Indocyanine Green Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping in Endometrial Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016; 23(7): 2206-2211.

- Imboden S, et al: Oncological safety and perioperative morbidity in low-risk endometrial cancer with sentinel lymph-node dissection. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019; 45(9): 1638-1643.

- Kapp DS, Shin JY, Chan JK: Prognostic factors and survival in 1396 patients with uterine leiomyosarcomas: emphasis on impact of lymphadenectomy and oophorectomy. Cancer. 2008; 112(4): 820-830.

- Bhatla N, et al: Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2019; 145(1): 129-135.

- Ramirez PT, et al: Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 2018; 379(20): 1895-1904.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2021; 9(3): 10-13.