The blood sugar level in the organism increases due to age. Lifestyle changes such as dietary modification and exercise, among others, can improve metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. In addition, however, early pharmacological treatment is recommended, as this can minimize diabetes-related long-term consequences.

Current guidelines recommend majority metformin for first-line treatment with antidiabetic agents. Advantages of the agent include weight neutrality, good response, and relative risk exclusion of hypoglycemia. Alternatives to metformin in patients with known renal insufficiency include sulfonylureas, glinides, GLP 1 agonists, and the DPPIV inhibitors, which can be used for initial treatment. If there is a known intolerance to metformin, pioglitazone is currently the glitazone of choice for initial treatment. However, there is still debate about the advantages and disadvantages of this antidiabetic drug, which is why it should only be administered in exceptional cases.

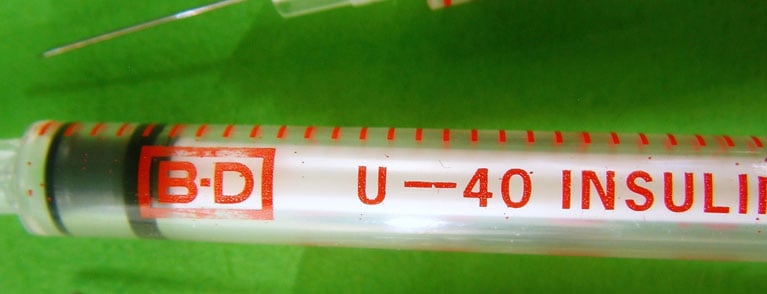

In the case of poor metabolic control, insulin is still an option for the initial treatment of type 2 diabetes. Advantages are that this allows glucose toxicity to be managed and subsequently treatment with oral antidiabetic agents can be restarted. In perioperative terms, insulin is also the first option, so that metabolism can be well controlled even if various other factors simultaneously affect glucose metabolism. Basically, a distinction is made between a post-aggression phase and a reparation phase. The first often occurs after trauma or surgery and is accompanied by insulin resistance, whereas in the second phase glucose can be better reabsorbed by peripheral tissues. The current antidiabetic groups can be found as an overview in Table 1.

New trends in metabolic control

In recent years, the conventional diabetes therapy method, which focuses on beta cell loss and insulin resistance, has been joined by newer promising pharmaceuticals as an alternative, which, among other things, mimic the effect of incretin.

Incretins such as GLP-1 exhibit a glucose-dependent action profile. Thus, they are triggered only when the blood glucose level rises above the fasting level. Existing research has focused primarily on GLP-1 in the context of bariatric surgery. According to the Hindgut hypothesis, food that bypasses a portion of the gastrointestinal tract is more likely to lead to and increase the stimulation of enterocrine cells in the gastrointestinal tract. The released GLP-1 causes stimulation of G protein-coupled receptors of pancreatic beta cells. In addition, GLP-1 also results in decreased release of glucagon, inhibiting glycogenolysis in the liver. Importantly, GLP-1 also triggers a decrease in appetite and increase in satiety. Besides, it also causes delay in gastric emptying [6]. The short half-life and rapid inactivation by dideptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP IV) of endogenous GLP-1 has led to the emergence of DPP IV-resistant GLP1 analogues, such as exenatide and liraglutide, and other antidiabetic agents that suppress DPP IV enzyme activity (sitagliptin, vildagliptin, saxagliptin). The therapeutic agent exenatide has been approved since 2005 and is generally injected subcutaneously twice daily. The relatively common side effects of exenatide are gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea [7]. Liraglutide is a newer agent that requires once-daily initiation and, as a GLP-1 analog, has a comparable mode of action to exenatide and is equally resistant to DPP-IV inhibitors.

DPP-IV inhibitors are commonly used as second-line drugs in diabetic patients. Especially in patients suffering from renal insufficiency and at increased risk of hypoglycemia, sitagliptin, for example, may be used as a suitable alternative.

GLP-1 agonists are usually administered to patients in whom treatment with other oral antidiabetic agents does not provide adequate glycemic control. Unlike the antidiabetic agents mentioned above, GLP-1 agonists must be administered subcutaneously. Advantages of these agents include the exclusion of hypoglycemic risk, as with metformin, and the ability to promote relatively good weight loss in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. The latter also qualifies GLP-1 agonists for use in the treatment of obese patients without type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The efficacy of α-glucosidase inhibitors is low compared with sulfonylureas or metformin. Their additional effect is the potential to lower HbA1c by approximately 0.5-0.8%.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- In type 2 diabetes, initial treatment is with metformin.

- According to the UKPDS study, metformin reduces cardiovascular risk in diabetics.

- If metabolic control is poor, therapy with insulin should still be used.

- Current diabetes therapies that focus on beta cell loss and insulin resistance are now alternatively supplemented by pharmaceuticals that act similarly to incretin (e.g., exenatide, liraglutide, sitagliptin).

Literature list at the publisher

Prof. Dr. med. Kaspar Berneis

CARDIOVASC 2013; 12(3): 33-35