Resistant germs are a major problem for doctors and patients worldwide. The development of a new substance, which is directed against a different target structure than previous drugs, is a possible solution. An interim assessment is positive, although results from preclinical tests are only available.

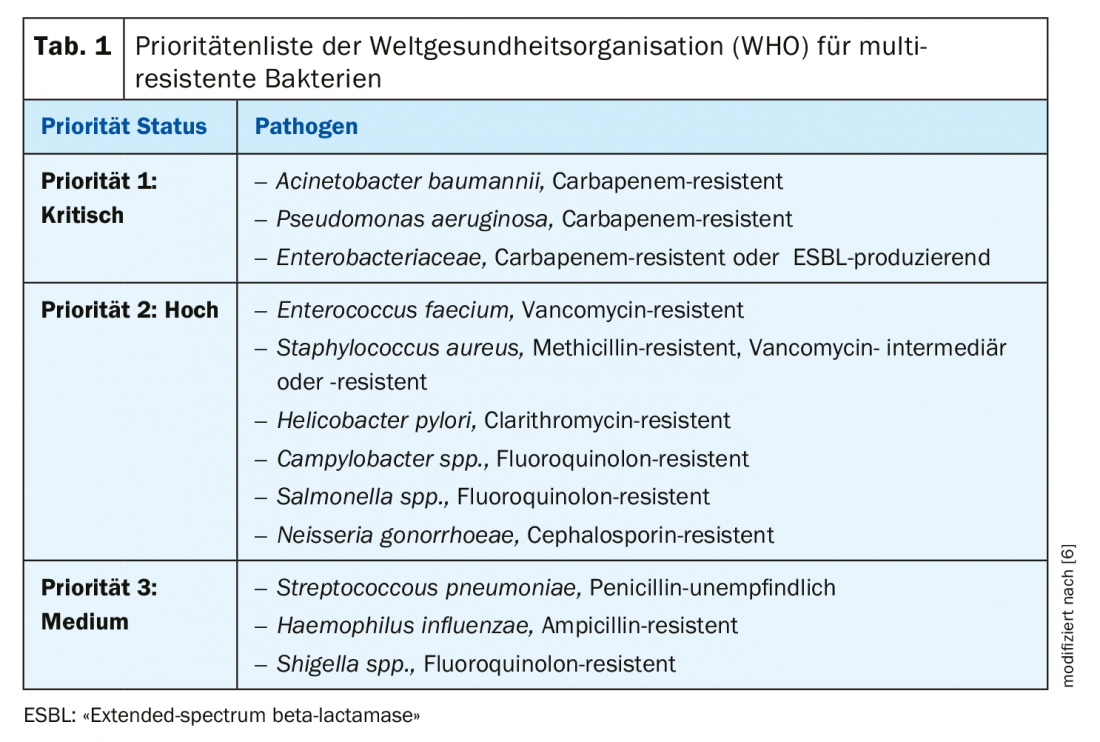

An increase in multidrug-resistant bacteria can cause routine surgical procedures and minor infections to become life-threatening and torpedo advances in modern medicine. Doctors and researchers fear that more and more people will have to deal with resistant germs in the future. The number of annual deaths due to drug-resistant infections is estimated to be as high as 50,000 in Europe and the United States [1].

Newly developed active ingredient in the research stage

Recently, scientists at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) have succeeded in developing a substance that is directed against the target pyruvate kinase – an enzyme that occurs in this form only in pathogenic bacteria and plays an important role in metabolism. Since this polypeptide has not been a drug target, bacteria have not yet developed resistance to it. In initial tests in cell cultures, this substance showed comparable efficacy to common antibiotics. In the best case, the new substances only act on the bacterial enzyme and thus the bacteria, so that there are as few side effects as possible. “In addition, this new target structure can be used to break existing antibiotic resistance,” explains Prof. Dr. Andreas Hilgeroth from the Institute of Pharmacy at MLU [2]. In experiments on the larvae of the great wax moth, a model organism, the researchers were able to confirm the effectiveness of the new substances. “These initial results give us confidence that we are on the right track,” says Prof. Hilgeroth. However, many more tests need to be performed before human clinical trials are possible. It may therefore take more than ten years before the substances developed by the German scientists become a marketable drug,

Forward-looking solutions in demand

The more frequently and the longer antibiotics are used, the higher the probability that the genetic material of bacteria will adapt accordingly and that they will become resistant [3]. Excessive use of antibiotics therefore favors the emergence of resistant germs, which applies not only to the field of human medicine. In conventional agriculture, too, animals are often treated en masse with antibiotics. Resistant bacteria from animal fattening can spread to humans. For example, the germ MRSA CC398 primarily colonizes people who come into professional contact with animals from fattening farms [4]. Research efforts to develop new antibiotics have been partially suspended, so that currently almost only variations of already established antibiotics are available. In the case of increasing resistance to the Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus species, such costly variations of already known antibiotics are sometimes a misinvestment, as the eventual benefit is small due to the expected risk of resistance development [5]. Just a few weeks ago, several major pharmaceutical companies announced that they would further scale back their own research into new antibiotics. “However, in order to treat infectious diseases reliably in the long term, we need new active substances to which bacteria have not yet developed resistance,” says Prof. Hilgeroth.

Literature:

- AMR: Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, www.amr-review.org

- Hilgeroth A: Prof. Dr. Andreas Hilgeroth, Institute of Pharmacy, Head of the Drug Development and Analysis Group, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, https://pc.pharmazie.uni-halle.de/

- Seethaler M, et al: Antibiotics 2019; 8(4): 210.

- Robert Koch Institute, www.rki.de

- Eades C, et al: Clinical Pharmacist 2017; 9 (9), DOI: 10.1211/CP.2017.20203363.

- WHO: World Health Organization, www.who.int

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(12): 6