UV exposure increases the risk of disease for both non-melanocytic skin cancer and malignant melanoma. A risk comes not only from sun exposure, but also from visits to solariums. This and many other current findings have been incorporated into the S3 guideline on skin cancer prevention, which was updated last year. Recent analyses confirm that skin cancer screening measures can help detect melanomas at earlier and thus prognostically favorable stages.

A total of 61 new recommendations were included in the guideline, which was updated under the leadership of the specialist societies Dermatological Prevention and Occupational and Environmental Dermatology, and 43 others were adapted [1,2]. Both the primary and secondary prevention sections have been revised. The chapters “Climate change and UV radiation” and “Occupational skin cancer” have been newly integrated. Both natural and man-made UV radiation is classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer ( IARC) as “carcinogenic to humans” (risk group I carcinogenic agents) [3].

Risk from UV exposure: what does the data say?

The relationship between UV radiation and the development of skin cancer has been demonstrated in a large number of scientific studies [1,3]. The likelihood of developing squamous cell carcinoma correlates with the cumulative UV dose to which a person has been exposed during his or her lifetime [1]. For basal cell carcinoma, both cumulative and intermittent UV exposures and sunburns appear to be important. And for malignant melanoma, intermittent UV exposures and sunburns at any age can increase skin cancer risk. Since this relationship is well known, the most important primary preventive measure is to avoid increased UV exposure [1]. Prof. Dr. med. Eckhard Breitbart, chairman of the working group Dermatologische prevention, points out that not only from natural, but also from artificially produced UV radiation risks go out: Solarium visitors and -besucher inside more frequently at skin cancer, this applies also to the particularly dangerous maligne melanoma. The risk of disease also increases with the frequency of solarium visits. The younger the tanning bed user was at the first visit, the higher the risk”, says the co-author of the guideline [2].

NMSC: especially cumulative UV exposure is crucial

In non-melanocytic skin cancer, UV exposure from natural or artificial radiation is the most important factor in disease development [1]. The fact that squamous cell carcinoma (PEC) and basal cell carcinoma (BCC) mostly develop on chronically UV-damaged skin or on areas of the body that are constantly exposed to light makes this connection clear. While the likelihood of developing PEK correlates with increasing lifetime acquired UV dose and occupational exposure, the dose-response relationship for BZK has not been fully elucidated [4,5]. In addition to intermittent exposure, recent studies show that cumulative UV exposure also plays a significant role, especially occupational solar exposure [4,6]. Sunburns also potentially increase the risk of BZK and PEK [1]. In addition, exposure to arsenic or tar, particularly in occupational settings, has been described as a risk factor, and there is evidence that HPV infection and use of the diuretic hydrochlorothiazide pose a risk [1,7].

Malignant melanoma: early detection through screening measures

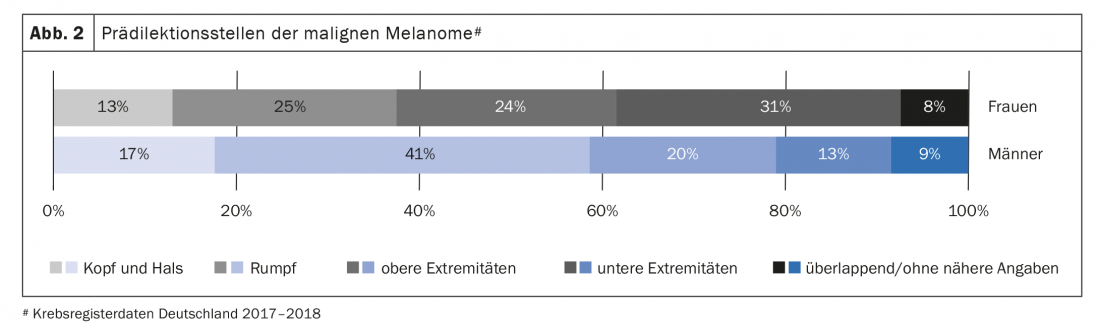

Avoidance of risk factors is the primary goal of skin cancer primary prevention, with UV exposure also being a significant etiologic factor for melanocytic tumors (box). At the level of secondary prevention is melanoma early detection. The stage of melanocytic tumors at initial diagnosis is an important guide to prognosis. In 2008, a structured skin cancer screening program was introduced in Germany. Since then, adults aged 35 and older have been able to have skin cancer screening performed every other year by family physicians, dermatologists and other specialists who have participated in appropriate training. As shown by epidemiological analyses of German cancer registry data, age-standardized disease rates for women and men jumped around 2008, whereas mortality rates have hardly changed since then [8] (Fig. 1) .

The results of an analysis published in the British Journal of Dermatology in 2021 also suggest that the skin cancer screening program established in Germany has a favorable effect on the prognosis of melanoma patients [9]. The cohort study was based on health insurance data of 1 431 327 individuals from the state of Saxony. In 2010-2016, of the incident melanoma cases, 1801 patients (73%) had received skin cancer screening within two years prior to their first melanoma diagnosis, while 674 patients (27%) were diagnosed without participating in screening [9]. In 704 of those patients who had claimed the skin cancer screening program, melanoma diagnosis was made within the first 30 days of screening. Compared with the comparison group, fewer locoregional metastases (4.2% vs. 13.5%) and fewer distant metastases (4.3% vs. 8.0%) were detected in the first 100 days after diagnosis. Treated with systemic cancer therapy within 30 days of diagnosis were 11.6% of melanoma patients in the screening participants versus 21.8% in the comparison group. Screening participants had significantly better survival in both the unadjusted Cox model (hazard ratio (HR): 0.37; 95% CI): 0.30-0.46) and after adjusting for

of all confounders (HR: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.48-0.80).

Literature:

- S3 Guideline: Prevention of Skin Cancer, Version 2.1 – September 2021, AWMF Register Number: 032/052OL, www.awmf.org, (last accessed 03/10/2022).

- Society Bulletins: Oncology Research and Treatment 2021; 44(5): 294-300.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): A review of human carcinogens. Part D: radiation, Lyon, France, 2012.

- Savoye I, et al: Patterns of ultraviolet radiation exposure and skin cancer risk: the E3N-SunExp Study. J Epidemiol 2018; 28(1): 27-33.

- Schmitt J, et al: Is ultraviolet exposure acquired at work the most important risk factor for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma? Results of the population-based case-control study FB-181. Br J Dermatol 2018a; 178(2): 462-472.

- Schmitt J, et al; Group, F. B. S.: Occupational UV exposure is a major risk factor for basal cell carcinoma: Results of the Population-Based Case-Control Study FB-181. J Occup Environ Med 2018b; 60(1): 36-43.

- Pedersen SA, et al: Hydrochlorothiazide use and risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer: A nationwide case-control study from Denmark. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78(4): 673-681. e679.

- Robert Koch Institute: Cancer in Germany: Malignant melanoma of the skin, Center for Cancer Registry Data, 13th edition, 2021, www.krebsdaten.de (last accessed 03/10/2022).

- Datzmann T, et al.: Patients benefit from participating in the German skin cancer screening program? A large cohort study based on administrative data. British Journal of Dermatology2021, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.20658.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2022, 32(2): 46-47

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2022; 10(2): 24-25.