Subclinical thyroid disease is common. Although latent hypofunction is often overtreated, the opposite may have an effect on mortality.

Subclinical thyroid disease is common. Approximately 13% are affected by subclinical hyperthyroidism [1], 4-8% in the younger population and 15-18% in the elderly population are affected by subclinical hypothyroidism [2]. When and how to treat?

Elderly hyperthyroid patients often poorly symptomatic

Latent hyperthyroidism is present when the TSH level is below the lower limit of the reference range and free T4 and T3 are normal. Etiologically, exogenous (hormone overtreatment) and endogenous causes can be distinguished; the latter include, in particular, Graves’ disease, toxic adenoma, and toxic nodular goiter. While Graves’ disease occurs predominantly in younger patients (<65 years) and in iodine-saturated areas, toxic adenoma and nodular goiter are more common in iodine-deficient areas and in older individuals [3]. According to data from the SHIP study, the gender distribution is roughly comparable (m=14%; f=20%) [1]. Looking at the referral rate of hyperthyroid patients, it is striking that significantly more younger patients with “more severe hyperthyroidism” are referred to specialized centers (up to 70%), whereas older patients remain in the care of primary care physicians as “milder cases” (referral occurs in 15-40%). However, Prof. Dr. med. Matthias Schott, Medical Director of Endocrinology at the University Hospital Düsseldorf (D), warns: “Especially the older patients have symptoms that are less easy to grasp: Loss of appetite, fatigue, weakness and depressed mood.”

Do patients with subclinical hyperthyroidism die earlier?

Although low TSH levels are often transient, latent hyperthyroidism should not be dismissed lightly – as it can result in cardiovascular and skeletal complications and impact mortality, among other things.

“Of course, patients with latent hyperthyroidism have an increased risk of developing atrial fibrillation,” Prof. Schott says. Thus, two large prospective studies showed a two- to threefold increased risk in elderly hypothyroid patients of developing atrial fibrillation. An increased incidence of atrial fibrillation in elderly patients with low TSH (0.1-0.5 mlU/l) has also been noted [4]. A meta-analysis with a follow-up of 8.8 years also showed a significantly higher incidence in individuals with subclinical hyperthyroidism and an attributable risk of 41.5%. Differences with respect to sex, age, or preexisting cardiovascular disease were not detected [5].

Although stroke is considered a potential complication of AF in manifest hyperthyroidism [6], this does not seem to be true with respect to subclinical hyperthyroidism.

Pooled data from a meta-analysis, however, show an association of subclinical hyperthyroidism and heart failure. Over the study period of 10.4 years, the HR for heart failure was significantly greater, especially in patients with subclinical hyperthyroidism type 2 (HR=1.94; 95% CI: 1.01-3.72) [7]. “Patients with latent hyperthyroidism have an increased risk of heart failure especially with a TSH level of <0.1 mU/l,” concludes Prof. Schott.

There is also an association with regard to coronary heart disease: patients with latent hyperthyroidism have a slightly increased risk of CHD events (HR=1.21), adjusted for age and sex, although no significant change in risk was found considering the degree of TSH depletion [5].

Blum and colleagues also confirmed an increased risk of osteoporosis in their meta-analysis involving thirteen prospective studies [8].

Last but not least, do patients with subclinical hyperthyroidism die earlier than euthyroid individuals? Collet and colleagues answered yes to this question. Their meta-analysis with a total of ten study cohorts (n=52 674) showed a small but significant increase in all-cause mortality [5]. The older the patients with latent hyperthyroidism, the greater the likelihood of dying from this hyperthyroidism due to excess mortality. This applies equally to men and women [9]. This was also the conclusion of a recent Danish cohort study of nearly 630,000 patients [10].

Thus, the indication for the treatment of latent hyperthyroidism is given in principle, summarizes Prof. Schott. The crucial question, he said, is how to treat them.

When does the subclinical hyperthyroid patient benefit from treatment?

Basically, three therapeutic options are available: medication, radioiodine therapy and surgery.

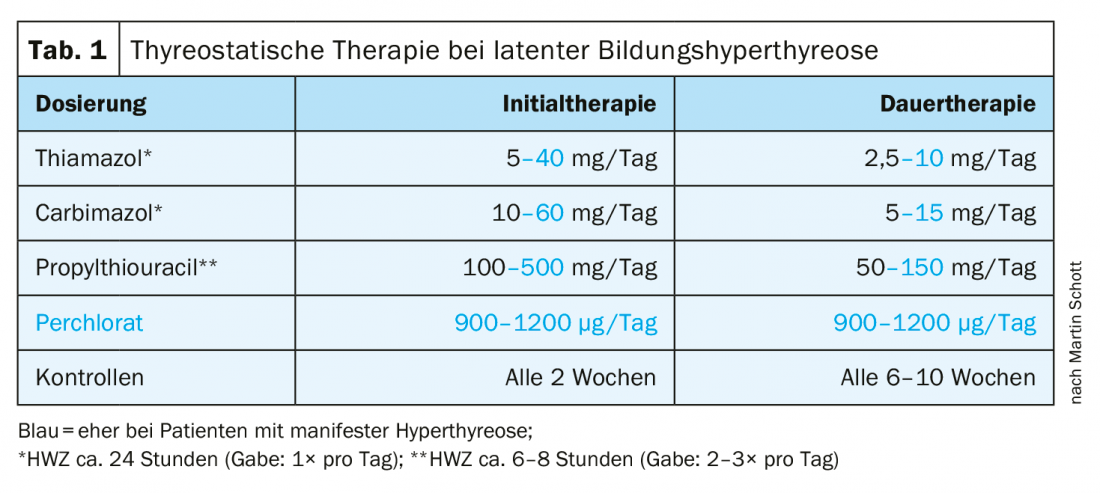

Medication: While in case of a release hyperthyroidism a symptomatic therapy is applied (if necessary with the use of beta-blockers), a formation hyperthyroidism is treated thyrostatically. This primarily involves the administration of low-dose thiamazole, carbimazole, or propylthiouracil. Due to the long half-life, a single daily administration is sufficient for thiamazole and carbimazole. Higher dosages must be administered two to three times per day (Tab. 1) . Controls should be performed at intervals of two weeks in the initial therapy and every six to ten weeks in the continuous therapy.

Operation: The indication is given if the thyroid gland is large (>50 ml), multiple, especially cold nodules are present, a quick “healing” is desired by the patient or soft tissue compression symptoms can be detected in this patient.

Radioiodine therapy: Radioiodine therapy is considered in cases of a normally large to moderately enlarged thyroid gland, in cases of previous thyroid surgery and (relative) contraindication to surgery. There must be no suspicion of carcinoma.

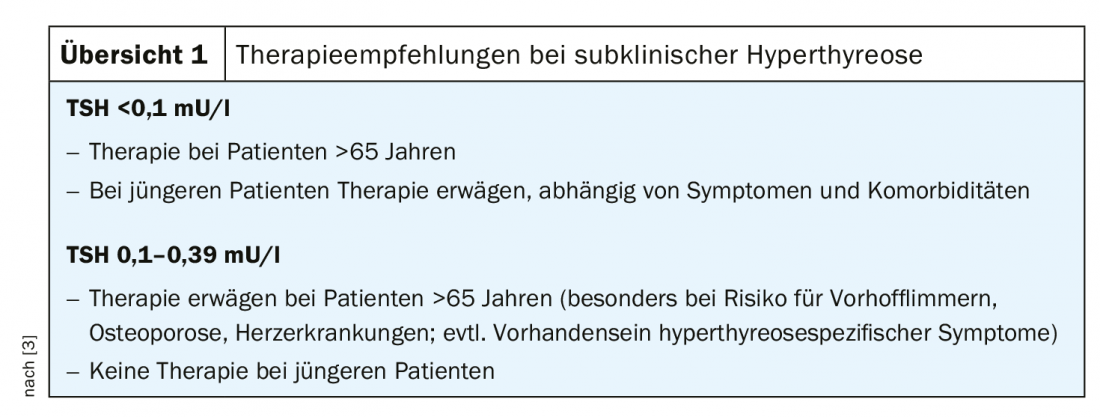

Prof. Schott summarizes: “If you have maximal TSH suppression and the patient is >65 years, ablative therapy should be given, usually with the help of radioiodine therapy, surgery depending on the size of the thyroid gland and the presence of nodules. In younger patients, therapy should be considered depending on potential symptoms and comorbidities.” If mild subclinical hyperthyroidism is present, treatment should be considered in patients >65 years. Younger patients do not benefit in this case (Overview 1).

“Beware of number crunching”

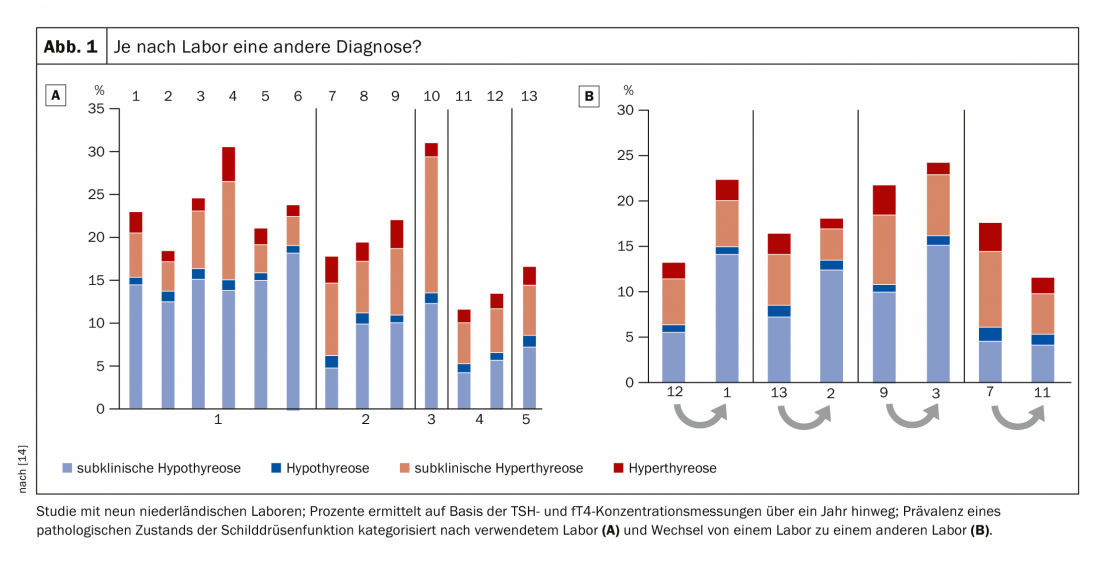

While latent hyperthyroidism tends to be underestimated, there is overtreatment with respect to latent hypothyroidism. The problem already starts with the TSH standard value. There has been debate about the upper standard limit for years, and the cutoff value of 2.5 mU/l is based on a statistical compromise [11]. And indeed, the TSH cutoff for the upper normal reference range could be confidently moved up 1-2 mU/l before fT4 measurement becomes necessary [12]. In a study with centenarians, it was found that they have much higher TSH levels, but – at least with regard to their thyroid function – are in perfect health [13]. Nevertheless, there is a tendency to want to define absolute TSH concentrations, which serve as a decision-making tool in the question of whether a patient should be observed more closely or even treated. Prof. Dr. med. Jörg Bojunga, Head of SP Endocrinology and Diabetology and Deputy Clinic Director of the University Hospital Frankfurt a.M. (D), takes a critical view of this. He refers not only to the construction of the cutoff value 2.5 mU/l, but equally to large differences in laboratory analysis. For example, one study investigated the extent to which the diagnosis of “subclinical hypothyroidism” was a “laboratory-induced” condition, so to speak. The result: depending on the laboratory, the evaluation of the same sample had between 6-15% deviation. The same happened when a sample was sent from laboratory 1 to laboratory 2 for retesting: The laboratory change alone doubled or halved the possibility for the patient to be diagnosed with subclinical hypothyroidism (Fig. 1) [14]. These results cast doubt on the absolute reliability of TSH/fT4 measurements. “This is purely a laboratory issue. So beware of number crunching!” warns Prof. Bojunga. “With subclinical findings a control is always necessary. In no case should one act directly!”, says the expert with regard to insurance data, according to which already far more than 90% receive a therapy already after a single TSH measurement.

99 out of 100 cases treated unnecessarily

In many cases, thyroid function normalizes without further intervention when TSH levels are initially high. Only in 1-5% of patients does subclinical develop into manifest hypothyroidism [15]. “This means that if you already treat after the first measurement, you are treating 99 out of 100 cases unnecessarily,” Prof. Bojunga points out; older people are particularly at risk of being over-treated.

So what about the risk of complications? While the risk of cardiovascular disease clearly increases in the presence of subclinical hyperthyroidism, latent hypothyroidism seems to have a positive overall effect: All-cause mortality tends to be lower. Although the data regarding myocardial infarction are borderline, the risk regarding heart failure, stroke, CHD (and incidentally cancer) is not increased up to a TSH level of 7 [16]. These two values, he said, must be remembered: “Between TSH 7 and 10, only CHD increases, heart failure does not actually increase, and only above a TSH of 10 does anything actually happen.” Amused conclusion of the speaker: “You obviously live longer with subclinical hypothyroidism”. There is also no evidence of a link between depression and latent hypothyroidism, nor of an effect on sexuality in women.

No levothyroxine in elderly comorbid patients!

The question of whether levothyroxine is useful for the treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism was investigated in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study published in 2017. This included 737 patients (≥65 years old) with persistent subclinical hypothyroidism. Over a study period of one year, there was no significant benefit of levothyroxine treatment [17]. Caveat: In patients with comorbidities, e.g. coronary artery disease, levothyroxine even increases mortality [18]!

Nevertheless, levothyroxine is most often prescribed at a TSH of 4.5-10. “In fact, the risk of mistakenly getting thyroid hormones has increased over the years. Two-thirds of those who got it were over sixty – and those are the ones who shouldn’t be getting it at all,” Prof. Bojunga elaborates. In addition, these patients had received only a single TSH measurement prior to initiation of therapy.

Looking at the gender ratio, it is mainly postmenopausal women who receive thyroid hormones.

When to treat?

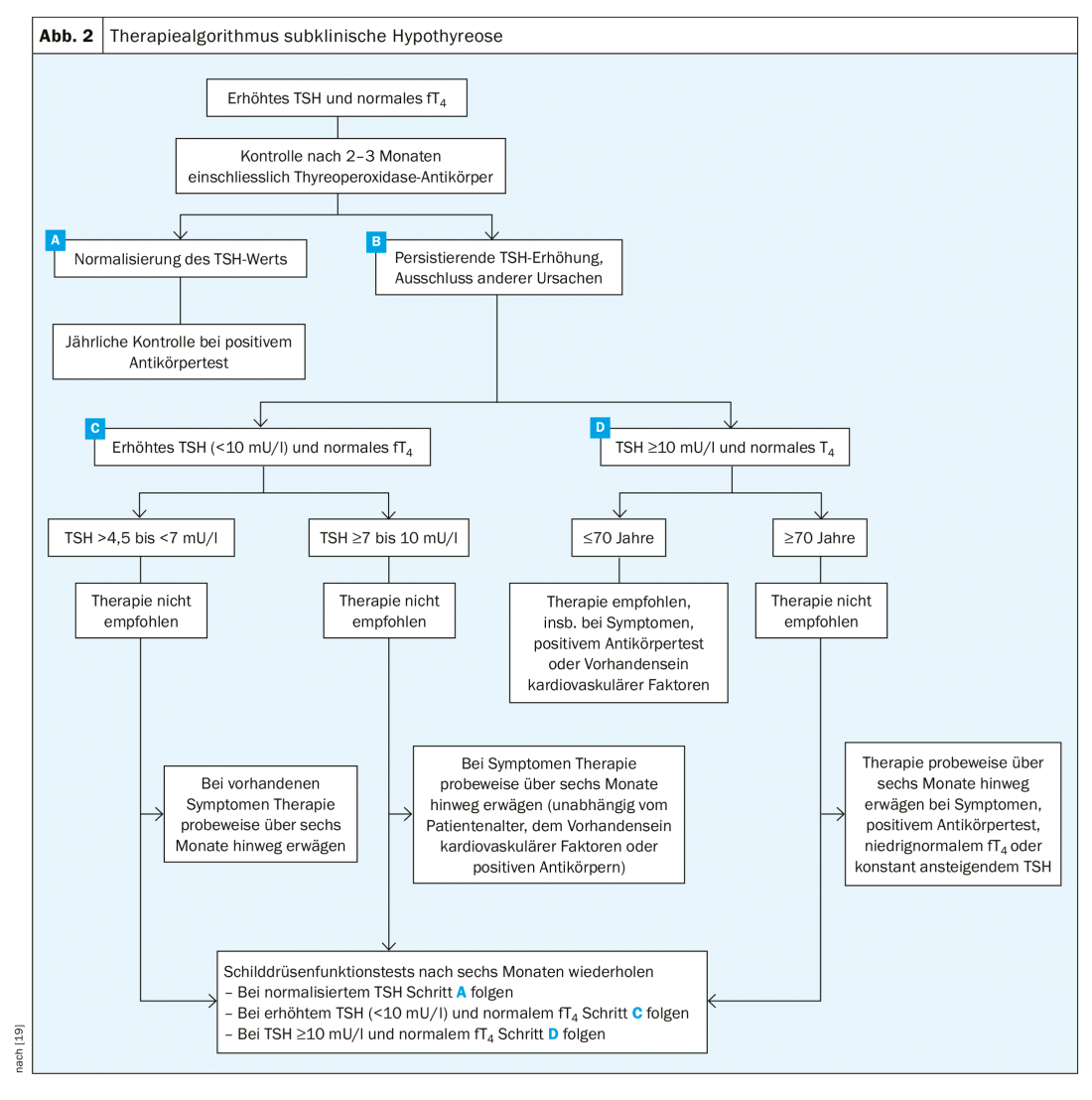

If the criteria for subclinical hypothyroidism are met (elevated TSH, normal fT4), the patient should be monitored after two to three months. Most of the time, the TSH level normalizes. On the other hand, if it is still elevated during control, it is first differentiated into <10 mU/l and ≥10 mU/l. Patient age is also relevant. If the patient is under seventy years of age and has a TSH level above 10 mU/l, administration of levothyroxine is indicated. Therapy may also be considered in cases of severe symptoms, increasing TSH levels over the years, and presence of antibodies. If therapy is started, the course should always be monitored. If the TSH level is >4.5 to <7 mU/l, treatment is usually not indicated. A treatment attempt may be made if the patient has severe hypofunction symptoms. For TSH values ≥7 to <10 mU/l, one can consider therapy earlier (Fig. 2) . “But overall,” Prof. Bojunga concludes, “there are few indications. People have become more cautious, and especially at the threshold values, they are more likely to do a check.”

Literature:

- Völzke H, et al: The prevalence of undiagnosed thyroid disorders in a previously iodine-deficient area. Thyroid 2003; 13(8) :803-810.

- Villar HC, et al: Thyroid hormone replacement for subclinical hypothyroidism. Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2007: CD003419.

- Biondi B, et al: The 2015 European Thyroid Association Guidelines on Diagnosis and Treatment of Endogenous Subclinical Hyperthyroidism. Eur Thyroid J 2015; 4: 149-163.

- Cappola AR, et al: Thyroid status, cardiovascular risk, and mortality in older adults. JAMA 2006; 295(9): 1033-1041.

- Collet TH, et al: Subclinical hyperthyroidism and the risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172(10): 799-809.

- Biondi B: Mechanisms in endocrinology: Heart failure and thyroid dysfunction. Eur J Endocrinol 2012; 167(5): 609-618.

- Gencer B, et al: Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and the risk of heart failure events: an individual participant data analysis from 6 prospective cohorts. Circulation. 2012; 126(9): 1040-1049.

- Blum MR, et al: Subclinical Thyroid Dysfunction and Fracture RiskA Meta-analysis. JAMA 2015; 313(20): 2055-2065.

- Haentjens P, et al: Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and mortality: an estimate of relative and absolute excess all-cause mortality based on time-to-event data from cohort studies. Eur J Endocrinol 2008; 159(3): 329-341.

- Selmer C, et al: Subclinical and overt thyroid dysfunction and risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: a large population study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014; 99(7): 2372-2382.

- Surks MI, Goswami G, Daniels GH: The Thyrotropin Reference Range Should Remain Unchanged. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90: 5489-5496.

- Henze M, et al: Rationalizing Thyroid Function Testing: Which TSH Cutoffs Are Optimal for Testing Free T4? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017; 102: 4235-4241.

- Atzmon G, et al: Extreme longevity is associated with increased serum thyrotropin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94(4): 1251-1254.

- Coene KLM, et al: Subclinical hypothyroidism: a “laboratory-induced” condition? Europ J Endocrinol 2015; 173: 499-505.

- Cooper DS, Biondi B: Subclinical thyroid disease. Lancet. 2012; 379(9821): 1142-1154.

- Floriani C, et al: Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and cardiovascular diseases: 2016 update. Europ Heart J 2017; 39: 503-507.

- Stott DJ, et al: Thyroid Hormone Therapy for Older Adults with Subclinical Hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 2534-2544.

- Nygaard Einfeldt M, et al: Long-Term Outcome in Patients With Heart Failure Treated With Levothyroxine: An Observational Nationwide Cohort Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019; 104: 1725-1734.

- Peeters RP: Subclinical hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 2556-2565.

FAMILY PRACTICE 2019; 14(8): 22-25