In Europe, chronic venous insufficiency is one of the most common causes of chronic wounds. In addition to surgical and invasive procedures, compression therapy is an important pillar in treatment. Among other things, the right compression class and suitable material properties are decisive for successful therapy, whereby individual circumstances must be taken into account. This is the conclusion of the s2k guideline prepared under the auspices of the German Society for Phlebology.

Venous leg ulcer (Fig. 1), also called open leg, is a chronic wound resulting from venous disease. When performed adequately, compression therapy causes an increase in venous return, a reduction in edema, and a removal of metabolites through pressure-induced constriction of venous vessels. By reducing pressure and volume overload in the venous system, pain is relieved [1,2]. The initially dry, scaly, hardened and yellow-brown discolored skin becomes softer and more supple again. In addition, compression therapy creates a stable abutment for the leg muscles, so that the work of the ankle and wall muscle pump in particular is intensified. Compression therapy can thus initially achieve peripheral decongestion and, in the further course, the healing of ulcerations.

Reduction of discomfort and improvement of the quality of life

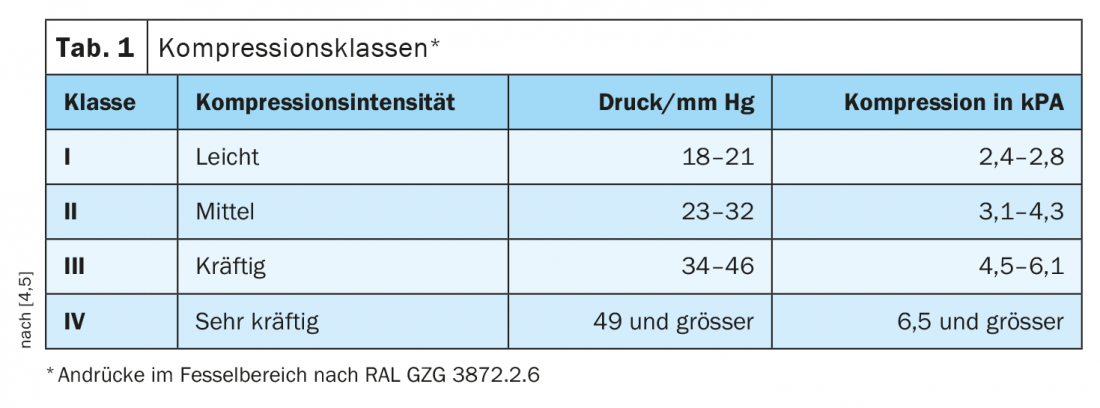

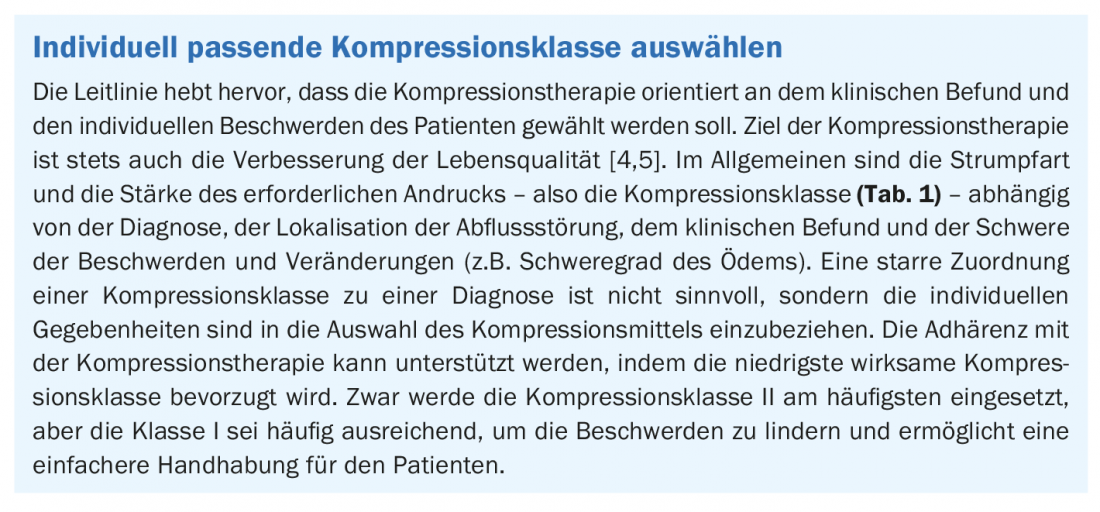

With continuous compression treatment with elastic bandages or with compression stockings, the healing rate for medium-sized wounds with a diameter of 1-5 cm is 50-70% after three months and 80-85% after six months [3]. The S2k guideline on medical compression therapy, published in 2019 under the auspices of the German Society of Phlebology and valid until 2023, summarizes the current evidence-based recommendations [4]. Medical compression stockings (MCS), phlebological compression bandages (PKV), and medical adaptive compression (MAK) systems are used [4]. The guideline places great emphasis on improving the quality of life of patients receiving compression. Only a carefully selected and individually fitting compression device can develop its full effect and contribute to the patient’s improved well-being; this also applies to the selection of the compression class (box) .

Decongestion phase vs. maintenance phase: What should be considered?

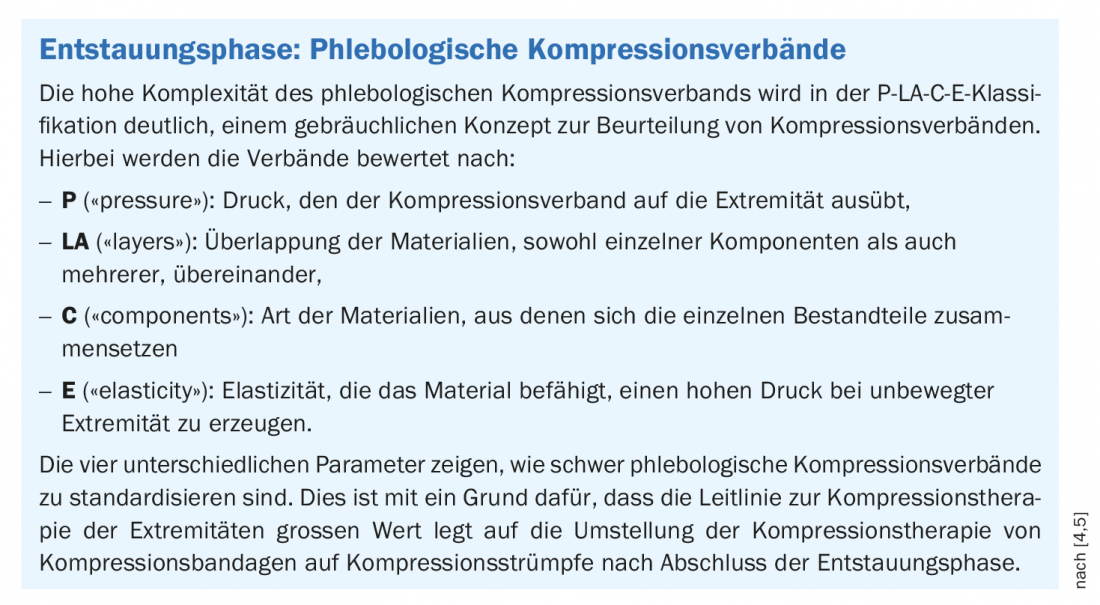

During the decongestive phase, strong compression care must be provided to reduce edema and support ulcer healing [5]. The phlebological compression bandage (box) should be applied with a high pressure. Especially for venous leg ulcer patients, the guideline emphasizes multicomponent systems in the decongestion phase. In contrast to short-stretch bandages, multicomponent systems are able to keep the contact pressure relatively constant over many hours or days. The new compression systems that have been available for a few years minimize the problems of application for the patient or the healthcare professional, which increases adherence. Due to the simpler application, such systems are more time-saving and less error-prone compared to complex compression bandaging [5].

After the initial decongestion phase, it is recommended to switch from phlebological compression bandages to double-layer ulcer compression stockings in appropriate cases. The advice to use primarily two-layer compression stockings in patients with venous leg ulcers is justified by the better practicability and the higher stiffness. The higher stiffness leads to faster and better healing.

Flat knit or circular knit materials?

According to the guideline, the criterion for prescribing flat knit fabric as an alternative to circular knit fabric is not primarily based on a specific diagnosis, but on specific findings of the patient. The decisive difference between flat knitted fabric and circular knitted fabric lies in the following three points: higher stiffness (higher ratio of working pressure to resting pressure, particularly important in the case of therapy-resistant edema), higher bending stiffness (more difficult for flat knitted fabric to slip into folds, thus fewer cord stitches), stitches in flat knitted fabric can be individually increased or decreased (therefore adaptation to unusual leg, arm or body circumferences is possible). [4,5]. For example, the guideline recommends prescribing a flat-knitted quality for relatively large circumferential changes in an extremity or for conically shaped extremities as well as for deepened tissue folds, since round-knitted material is not suitable for fitting in certain anatomical conditions [4].

Avoid mechanically induced incompatibilities

More common than allergic reactions are mechanically induced intolerances to compression materials. It has not been proven that a particular bandaging technique, for example according to Pütter, Sigg or Fischer, is superior to another [5]. The guideline indicates attention to the following aspects regarding compression bandaging:

- A tubular bandage made of cotton, which is pulled on to below the knee, serves as skin protection.

- Underpadding can help prevent pressure ulceration.

- Pressure pads and pads can further enhance the effectiveness.

- Plaster fixation strips are suitable for securing the bandage closure; fixation clips pose a risk of injury.

- The width of the bandage is based on the shape and diameter of the respective body part.

- At least two bandages are usually required for proper compression care.

- The foot is always in functional position (dorsal extension).

- Already at the beginning, good investment pressure must be ensured. Too loose tours, e.g. on the forefoot, can lead to edema formation.

- The bandage roll is unrolled directly on the skin under permanent tension, so that the bandage is evenly molded to the leg.

- Tightening individual binding turns too tightly disturbs the pressure gradient. For example, constriction can lead to venous congestion (up to an increase in the risk of thrombosis), nervous pressure damage or necrosis.

- In the case of pronounced forefoot edema or lymphedema, the toes should also be compressed to prevent the influence of edema.

Are there any contraindications or risks?

In the run-up to compression therapy, it is important to determine risks and contraindications and to adjust the therapy accordingly on an individual basis. According to the guideline, the following risks and contraindications to medical compression therapy should be considered [4]:

Contraindications:

- Advanced peripheral arterial disease if any of these parameters apply: ABPI <0.5, ankle artery pressure <60 mmHg, toe pressure <30 mmHg, or TcPO2 <20 mmHg dorsum of foot If inelastic materials are used, compression fitting can still be attempted with ankle artery pressure between 50 -60 mmHg under close clinical monitoring.

- Decompensated heart failure (NYHA III + IV)

- Septic phlebitis

- Phlegmasia coerulea dolens

Risks:

- Pronounced weeping dermatoses

- Intolerance to compression material

- Severe sensitivity disorders of the extremity

- Advanced peripheral neuropathy (e.g. in diabetes mellitus)

- Primary chronic polyarthritis

In these cases, the treatment decision should be made by weighing the benefits against the risks and selecting the most appropriate compression device. Improper bandaging (excessive contact pressures, strangulation) causes pain and can result in tissue damage and even necrosis and pressure damage to peripheral nerves, especially bony prominences (caveat: fibular heads) [7,8].

Side effects and risks of compression therapy can be avoided by following the rules of proper implementation. This includes padding pressure-prone areas and regular skin care. The following symptoms should lead to immediate removal of the compression fitting and control of the clinical findings: Blue or white discoloration of the toes, sensory disturbances and numbness, increasing pain, shortness of breath and sweating, acute movement restrictions.

Literature:

- Dissemond J, et al: Compression therapy of venous leg ulcers in the decongestive phase. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed DOI 10.1007/s00063-016-0254-9.

- Dissemond J, et al: Compression therapy of leg ulcers. Der Hautarzt 2016; 67: 311-325.

- University Hospital Zurich: The open leg (Ulcus cruris venosum), www.usz.ch/app/uploads/2020/07/M_Broschuere_Ulcus-2016_A5_INTERNET_TW.pdf

- Rabe E, et al: s2k-Leitlinie: Medizinische Kompressionstherapie der Extremitäten mit Medizinischem Kompressionsstrumpf (MKS), Phlebologischem Kompressionsverband (PKV) und Medizinischen adaptiven Kompressionssystemen (MAK), www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/037-005.html

- Stücker M, Rabe E : The new S2k guideline: Medical compression therapy of the extremities with medical compression stocking (MCS), phlebological compression bandage (PCB) and medical adaptive compression systems (MAK). Phlebology 2019; 48: 321-324

- Mosti G, Iabichella ML, Partsch H: Compression therapy in mixed ulcers increases venous output and arterial perfusion. J Vasc Surg 2012; 55: 122-128.

- Chan CLH, et al: Toe ulceration with compression bandaging: observational study. BMJ 2001; 323: 1099.

- Usmani N, Baxter KF, Sheehan-Daze R: Partially reversible common peroneal nerve pulse secondary to compression with four-layer bandaging in a chronic case of venous ulceration. Br J Derm 2004; 150: 1224-1225.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2021; 31(6): 16-18