An intracranial aneurysm is a potentially life-threatening condition and should be referred to a specialized clinic for evaluation. Treatment is possible both surgically and endovascularly and should be decided by a team proficient in both techniques. The risk of treatment is low in skilled hands and is compared to the individual risk of rupture. Ruptured aneurysms should be treated within 24 h because of the high risk of rupture.

Intracranial aneurysms present a challenge to the treating neurosurgeon. In addition to the treatment procedures, which require special technical skills from the neurosurgeon, the decision-making process as to whether and with which technique a particular aneurysm must be treated is particularly demanding. In ruptured aneurysms, which are usually associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage that is severe for the patient, there is a clear indication for immediate treatment because of the increased risk of re-rupture within the first few weeks. In nonruptured aneurysms, the risk of rupture must be carefully weighed against the risk of treatment and discussed in detail with the patient. In principle, there are two well-established treatment approaches for both ruptured and non-ruptured aneurysms: In addition to microsurgical closure of the aneurysm with a titanium clip from the outside (microsurgical clipping), it is also possible to close the aneurysm by inserting platinum chips through a microcatheter through the groin (endovascular coiling). There are advantages and disadvantages for both procedures and other less frequently used treatment options, which are nowadays determined on an interdisciplinary and patient-specific basis.

Introduction (epidemiology, pathophysiology, and risk factors).

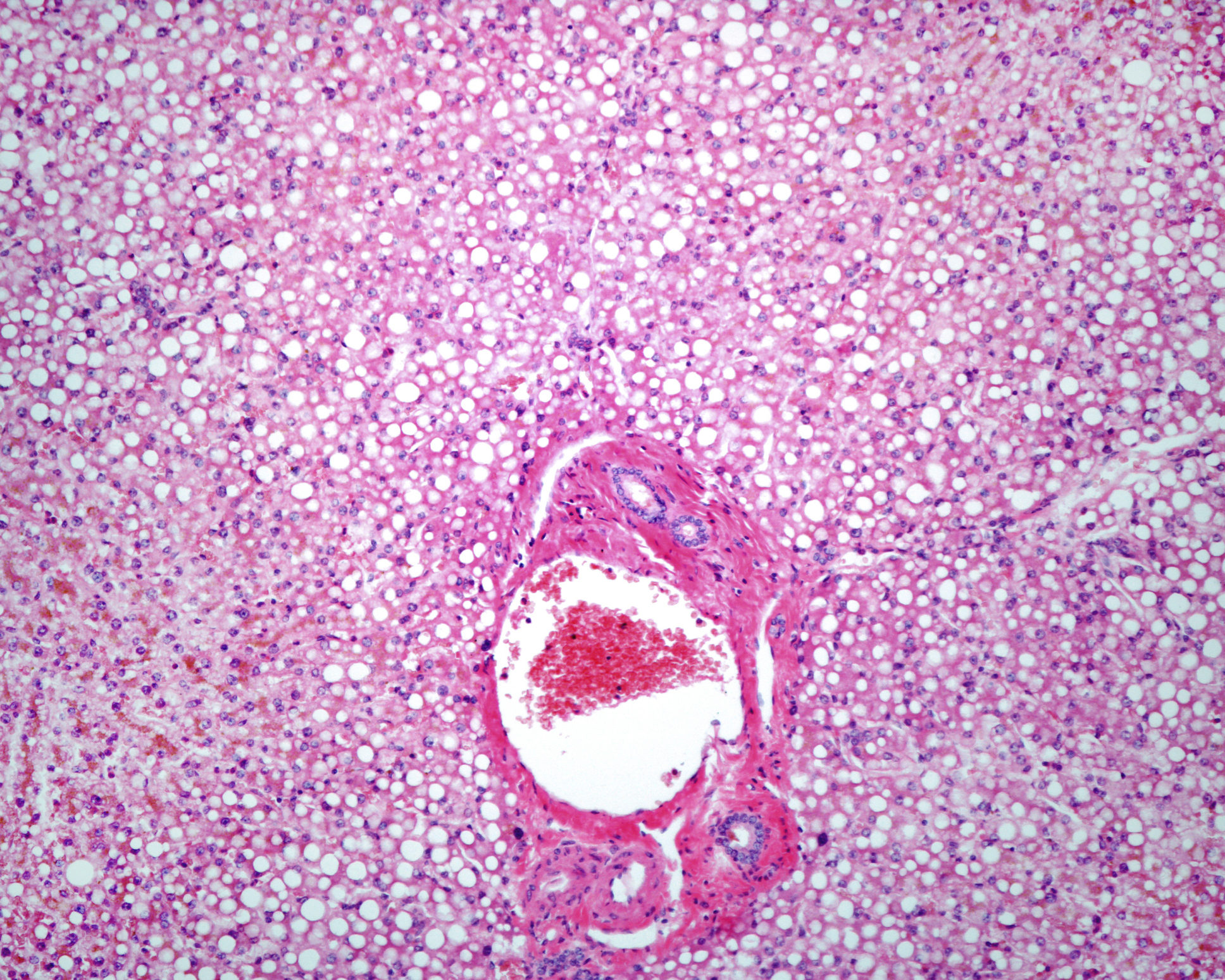

Intracranial aneurysms are bulges of the arterial wall, which mostly develop at vessel branches and occur with a prevalence of about 3.2% in the adult population [1,2]. The most common types of aneurysms are saccular aneurysms, followed by fusiform aneurysms, which involve an entire segment of the vessel (Fig. 1A). The exact cause of intracranial aneurysms is unknown, but a number of factors are thought to play a role in their development. In addition to a genetic predisposition, hemodynamic stress and inflammatory reactions in the area of the vessel wall can also lead to remodeling of the latter and promote aneurysm formation [2,3]. Patients suffering from polycystic kidney disease and connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome also have an increased risk of developing an aneurysm. Also, cardiovascular risk factors such as cigarette use and hypertension, as well as patients with positive family history are associated with aneurysm development [2].

Treatment of non-ruptured aneurysms

In nonruptured aneurysms, the risk of rupture must be carefully weighed against the risk of treatment and discussed in detail with the patient. Most often, these aneurysms are diagnosed as incidental findings on MRI or CT scans, and affected patients are symptom-free. Especially in this situation, the detailed patient discussion with pointing out risk factors and explaining possible treatment options and their risks is very important [4].

It is well known that aneurysm size is an important risk factor for rupture. In addition to aneurysm size, a multicenter prospective study (ISUIA) further demonstrated that aneurysm location also influences rupture risk [5,6]. In this regard, aneurysms in the vertebrobasilar stromal area have an increased risk of rupture. However, in addition to these radiologic criteria, patient-specific factors (age, ethnicity, arterial hypertension, and nicotine use), as well as a history of SAB due to another intracranial aneurysm, are important risk factors that must be considered in the treatment decision [2]. Based on clinical studies, some scores, such as the PHASES score, have been published within the last years to help in decision making [7,8]. If the risk of rupture outweighs the risk of treatment, treatment of the aneurysm is recommended. Nowadays, at large centers – such as ours at the University Hospital Zurich – these decisions are determined in an interdisciplinary neurovascular conference and subsequently discussed with the patient.

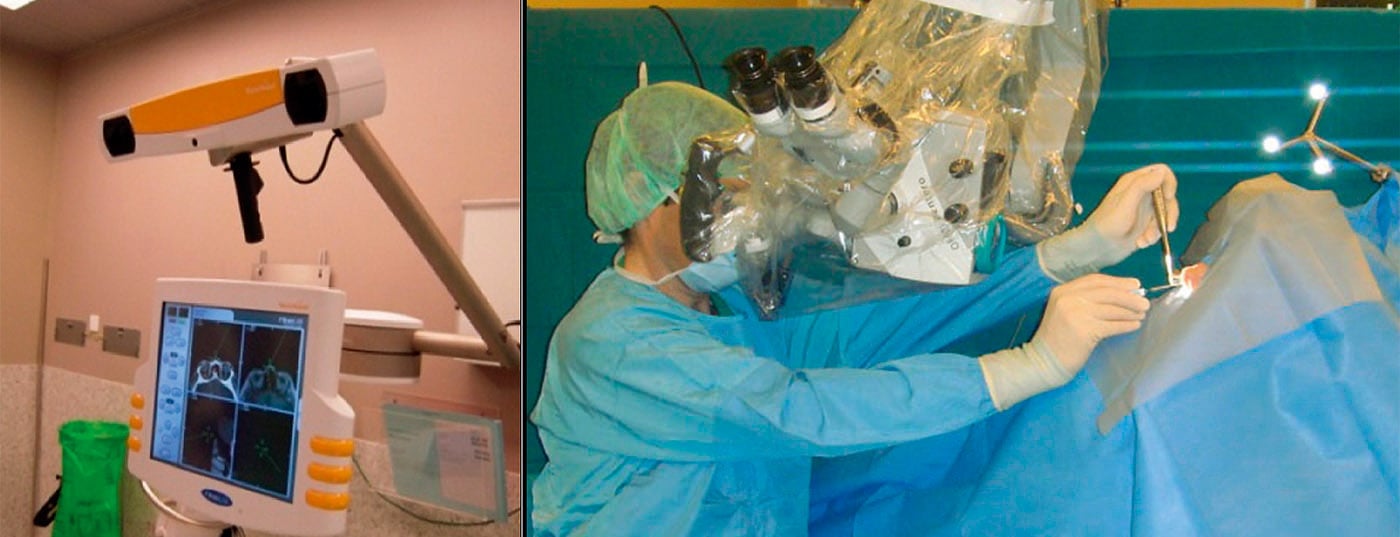

Once the decision to treat the aneurysm has been made, the best possible procedure for the patient must be found on an individual basis. In principle, two treatment methods are available today to close the aneurysm: microsurgical surgical closure of the aneurysm with a titanium clip (microsurgical clipping) and the microcatheter-based procedure through the groin with closure of the aneurysm by insertion of platinum chips into the aneurysmal lumen (endovascular coiling) (Fig. 1B) [2]. There are advantages and disadvantages to both procedures and other less commonly used treatment options. In elderly patients and aneurysms localized in the posterior circuit, endovascular treatment is preferable because the surgical treatment risk tends to be higher than the endovascular treatment risk. Aneurysms that have a narrow aneurysm neck are very amenable to endovascular treatment. Surgical clipping is recommended in younger patients, aneurysms with a wide neck, and especially distally located aneurysms (e.g., aneurysms of the medial bifurcation), as these cannot always be completely eliminated with the endovascular technique. In addition, the risk of recurrence is much lower in clipped patients, which is precisely what must be considered in young patients. If clipping is not possible in a special type of aneurysm with a very thin and fragile aneurysm wall (blister aneurysm), the aneurysm can be treated with the help of the wrapping technique, in which the vessel wall is supported with muscle, absorbent cotton or Teflon. In rare cases, when the aneurysm involves the whole vessel wall (fusiform aneurysms), the vessel can be reconstructed endovascularly with a special stent (e.g. “flow diverter”) – but here the data are not yet evident. (Fig.1B). If the distal brain area is sufficiently supplied by other vessels, the vessel can also be completely occluded (“trapping”). If the blood supply is insufficient, it is sometimes necessary to maintain the flow in the section of the vessel to be occluded by means of an extracranial-intracranial bypass. Such a bypass can also be used for complex saccular aneurysms with a vascular outlet incorporated in the aneurysm.

In rare cases, intracranial-intracranial bypass may also be considered if two vessels are anatomically in a very close positional relationship to each other (e.g., in aneurysms of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery) (Fig. 1C). These complex procedures are only offered at highly specialized centers.

Treatment of ruptured aneurysms

The incidence for ruptured aneurysm with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAB) is approximately six to eight per 100,000 per year, and 50-60% of these patients die directly or as a result of SAB [2]. The risk of re-rupture in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage is very high and is approximately 2% per day within the first two weeks, 40% after one month, and 50% after six months unless the aneurysm is treated [2]. For this reason, treatment of a ruptured aneurysm is recommended within 24 h practically. Treatment procedures are analogous to those for nonruptured aneurysms, but nowadays digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is recommended first in stable patients for accurate aneurysm visualization and exclusion of other aneurysms; an attempt at endovascular closure may be performed in the same session [9,10]. If complete coiling is not possible, surgical treatment with clipping should be performed. In young patients, good clinical condition, certain peripheral aneurysmal localizations (MCA bifurcation), or patients with additional intracerebral hemorrhage requiring additional hematoma evacuation, surgical clipping is usually primarily recommended.

Despite the regular occlusion of the aneurysm and the resulting very low risk of rupture, SAB patients still face other risks within the first weeks after the bleeding event. In addition to CSF outflow obstruction due to hemorrhage components in the ventricular system (hydrocephalus) and a possible epileptic seizure, these include cerebral vasospasm, which can become symptomatic in up to 20% of patients and can lead to severe ischemia [2]. For this reason, aneurysmal SAB patients must be monitored closely neurologically in a specialized intensive care unit for immediate initiation of surgical hydrocephalus treatment (creation of an external ventricular drain or ventriculo-peritoneal shunt) or drug/endovascular vasospasm treatment, if necessary.

Summary

Nowadays, both microchiurgical and endovascular procedures are available for the treatment of cerebral aneurysms. Which technique is chosen should be determined on a patient-specific and interdisciplinary basis. Ruptured aneurysms must be treated immediately because of the high risk of rupture, and the risk of rupture must be weighed against the risk of treatment for incisional, asymptomatic aneurysms.

Literature:

- Vlak MH, et al: Prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms, with emphasis on sex, age, comorbidity, country, and time period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2011; 10: 626-636.

- Fusco MR, et al: Surgical and endovascular management of cerebral aneurysms. Int Anesthesiol Clin 2015; 53: 146-165.

- Hashimoto T, et al: Intracranial aneurysms: links among inflammation, hemodynamics and vascular remodeling. Neurol Res 2006; 28: 372-380.

- Burkhardt JK, et al: [Intracerebral aneurysm – treatment options, informed consent, and legal aspects]. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2011; 105: 535-541.

- Houdart E: Comment on the article “Unruptured intracranial aneurysms – risk of rupture and risks of surgical intervention. International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms Investigators”. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 1725-1733.

- Wiebers DO, et al: International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms I. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet 2003; 362: 103-110.

- Backes D, et al: PHASES Score for Prediction of Intracranial Aneurysm Growth. Stroke 2015; 46: 1221-1226.

- Etminan N, et al: The unruptured intracranial aneurysm treatment score: a multidisciplinary consensus. Neurology 2015; 85: 881-889.

- Molyneux A, et al: International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial Collaborative G. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised trial. Lancet 2002; 360: 1267-1274.

- Spetzler RF, et al: The Barrow Ruptured Aneurysm Trial: 6-year results. J Neurosurg 2015; 123: 609-617.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(5): 26-28.