The common cold is one of the most common infections in outpatient medicine. It is usually treated purely symptomatically. Antibiotics are indicated only for superinfections caused by bacteria.

Influenza and the common cold are everyday terms for infections of the respiratory tract that are not sharply defined in medical terms. It includes all diseases with inflammation of the nasal, pharyngeal and tracheal mucosa. The fuzzy term “flu-like infection” reflects the overlapping symptomatology between influenza virus infection and the other viral infections of the upper respiratory tract. Therefore, a cold or flu-like infection should ideally be referred to as an “upper respiratory tract infection.” The term “flu” or “influenza,” on the other hand, should be used only for infection with influenza viruses.

Upper respiratory tract infection is one of the most common acute illnesses in industrialized countries. The incidence is inversely proportional to age. On average, an adult has one to three upper respiratory tract infections per year. Children suffer up to eleven upper respiratory tract infections per year, depending on age. Despite the mostly benign and self-limiting course, the common cold has a very gossen social and economic impact. There are increased visits to the doctor, absences from school and work.

Etiology and pathogenesis

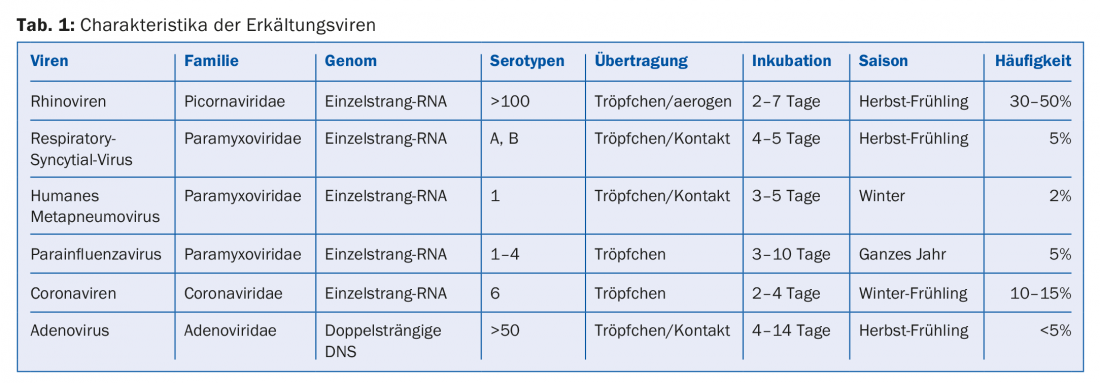

Although upper respiratory tract infection might be thought of as a single disease, etiologically more than 200 different viruses are responsible (Table 1), the most common being rhinoviruses (40%). Since the discovery of rhinoviruses in 1956, more than 160 different serotypes have been described; they are transmitted mostly via autoinoculation after contact with contaminated objects or via droplet infection. Reservoirs of rhinoviruses are mainly school children.

Parainfluenza viruses are the most common cause of acute laryngotracheobronchitis in children and they cause 5% of colds. They are also transmitted via direct contact or via large droplets. The incubation period is three to six days. One-third of children with a pulmonary infection with a parainfluenza virus develop a bacterial superinfection.

Coronaviruses cause 7-26% of viral respiratory illnesses in adults. Because of the short immunity to this pathogen, reinfections occur frequently. Transmission is usually by droplets, but smear infections are also possible.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) occurs in 10-15% of cases. Transmission is usually by droplet or smear infection. Immunity to RSV is incomplete, which can lead to reinfection. Globally, RSV is the most common causative agent of lower respiratory tract infections in children, with more than three million hospitalizations and up to 200,000 deaths of children under five years of age each year.

Adenoviruses are responsible for about 5% of flu infections. The incubation period is usually four to seven days, but can last up to two weeks. Transmission occurs via droplets, direct inoculation of the conjunctiva, feco-orally, or via contact with adenovirus-populated surfaces.

In young children, human metapneumovirus is the second most common virus isolated in colds. It is genetically and clinically related to the more common RSV from the same subfamily Pneumovirinae. By the age of five, most children have developed antibodies to human metapneumovirus, even without having had a severe lower respiratory infection.

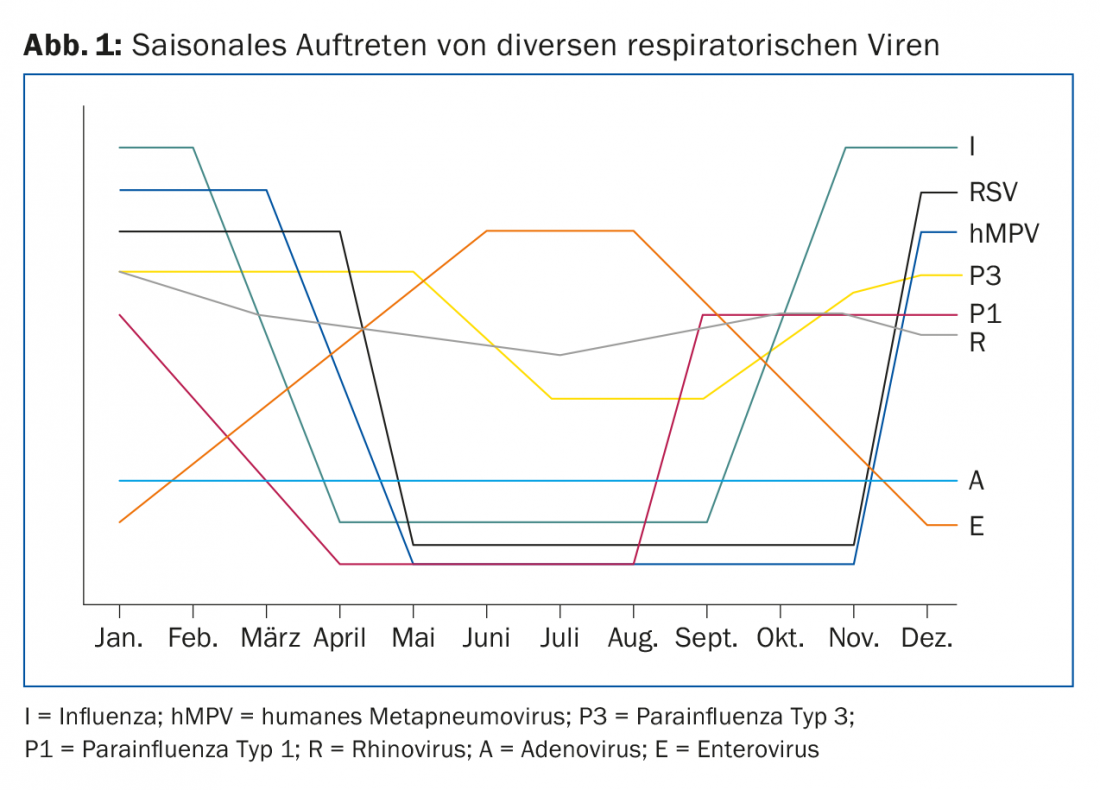

The occurrence of flu-like infections depends on the seasons. Depending on the season, other pathogens also occur (Tab. 1 and Fig. 1). RSV infections occur primarily in the winter months with a peak between January and March. Although rhinoviruses are isolated throughout the year, they are clustered in the fall through spring.

Symptomatology

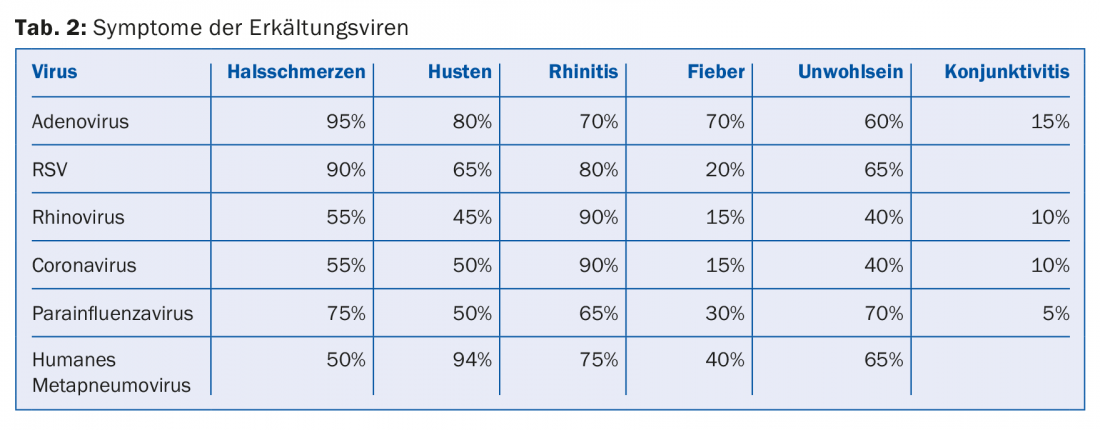

Symptoms may vary among the different viral diseases (Tab. 2). Rhinovirus infection usually begins with a scratchy throat, followed by difficulty swallowing and sore throat. The most important leading symptom of a cold is rhinitis, which often appears only a short time later than the initial symptoms. The sore throat usually resolves more quickly and the rhinorrhea becomes increasingly purulent, but this should not be interpreted as a sign of bacterial superinfection. Usually, adults with a rhinovirus infection are afebrile; fever is more common in children.

Other symptoms of a cold include headache and aching limbs, which usually last for four to five days. During this phase of the disease, depending on the virus, adults may also develop a slight fever (tab. 2) . From about the sixth day, a dry, irritating cough may set in, which can also persist for a longer period of time. As a rule, however, the disease is over after a week.

Complications

The common cold is usually a benign, self-limiting condition. It lasts on average seven to ten days. But serious complications such as secondary bacterial superinfections, exacerbations of bronchial asthma or COPD can also occur. In children with a viral upper respiratory tract infection, the most common bacterial complication is otitis media (20%).

Other common complication of a cold is sinusitis or pneumonia. Bacterial sinusitis occurs in only about 0.5-2% of cases. Complaints of the sinuses are much more common in upper respiratory tract infections and are seen as part of the viral infection. In contrast, pneumonias are most commonly caused by bacterial superinfections of the common cold.

Studies have shown that infectious exacerbations of asthma or chronic obstructive pneumopathy are associated with viral upper respiratory tract infections.

The mortality of elderly patients with a viral respiratory infection is often underestimated. Studies have also shown that two-thirds of patients may develop bronchitis or pneumonia.

Diagnostics

The diagnosis of a cold is usually made purely clinically. The differential diagnosis must always include the “real” flu, i.e. influenza. In this case, PCR can be helpful in establishing the diagnosis. Several multiplex PCR systems (e.g. BioFire FilmArray®) are commercially available that can be used to detect multiple cold and influenza viruses.

Likewise, strep throat can often resemble the symptoms of an early cold. Here, a rapid antigen test or conventional microbiological culture can be used to make the correct diagnosis.

Therapy

The therapy of a cold is usually purely symptomatic. Patients most often suffer from rhinorrhea, so the short-term use of decongestant nasal drops plays a major role here. The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetylsalicylic acid and paracetamol is the most common remedy to relieve the classic cold symptoms. Cough suppressants and mucolytics are also commonly used for symptomatic therapy.

Since these are viral infections, the use of antibiotics is not appropriate. However, if a complication occurs with a bacterial superinfection such as pneumonia, antibiotic therapy is essential.

Conclusion

In summary, influenza infection is one of the most common diseases in outpatient medicine. Different viruses can be responsible for a cold. As a rule, symptomatic therapy of flu-like symptoms is quite sufficient.

Take-Home Messages

- The common cold is one of the most common infections in outpatient medicine.

- The most common symptoms are rhinorrhea, sore throat and cough.

- Influenza is a viral infection and is usually treated purely symptomatically.

- Antibiotic therapy should be given only in cases of superinfections caused by bacteria.

Further reading:

- Heikkinen T, Järvinen A: The common cold. Lancet 2003 Jan 4; 361(9351): 51-59.

- Eccles R: Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis 2005 Nov; 5(11): 718-725.

- Wat D: The common cold: a review of the literature. Eur J Intern Med 2004 Apr; 15(2): 79-88.

- Passioti M, et al: The common cold: potential for future prevention or cure. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2014 Feb; 14(2): 413.

- Kirkpatrick GL: The common cold. Prim Care 1996 Dec; 23(4): 657-675.

- Padberg J, Bauer T: [Common cold]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2006 Oct 20; 131(42): 2341-2349.

- Jackson Allen P, Simenson S: Management of common cold symptoms with over-the-counter medications: clearing the confusion. Postgrad Med 2013 Jan; 125(1): 73-81.

- Walter JM, Wunderink RG: Severe Respiratory Viral Infections: New Evidence and Changing Paradigms. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2017 Sep; 31(3): 455-474.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(11): 12-14