Atopic dermatitis (AD), also called atopic eczema or neurodermatitis atopica, is one of the most common skin diseases. A typical feature is the chronic occurrence of inflammatory skin changes with itching, which progresses in episodes. The exact cause of this multifactorial disease is unclear, although the combination of external and internal disturbances can be considered certain. The following article provides an overview of the most common symptoms of AD and diagnostic options.

Most sufferers are diagnosed with AD in the first two years of life. More than half already have typical symptoms in the first year of life, and in about 70% the disease begins by the fifth year of life. In the course of the disease, the symptoms can improve or even heal in the majority of cases, but in 20% a persistent course and in 7% an episodic occurrence of the disease can be found. Less than 5% are affected by a severe course. Rarely, in about 1.5-3%, AD develops in adulthood. Why prevalence has increased significantly in recent years is a matter of controversy. In addition to improved hygiene measures and thus reduced exposure to pathogens, changes in living conditions (urban vs. rural environment, climate, nutrition and environmental influences) are also being considered.

State of knowledge regarding etiology

What is the cause of AD now? To date, several disorders are suspected, although the exact cause of this multifactorial disease remains unclear in its completeness. The combination of external and internal disturbances can be considered certain.

Clinically, sufferers show sensitive and dry skin. This is caused by a disturbance of the physiological barrier function mainly of the uppermost skin layer (stratum corneum), which is associated with skin dryness, irritability and increased transepidermal water loss as well as a reduced water-binding capacity.

The barrier defect is caused by various plant-related disorders:

- Defects in the epidermal differentiation of keratinocytes can facilitate the penetration of interfering factors such as toxic and allergenic substances from the environment. The result is damage to the keratinocyte membrane, leading to cytokine release and inflammation. Clinically, a worsening of atopic dermatitis can be observed as a result of irritants such as soap, wool or even water.

- Mutations in the filaggrin gene in atopics cause a reduced expression of skin barrier proteins and the filaggrins, which are degraded to amino acids as one of the so-called “natural moisturizing factors” responsible for water retention in the horny layer. The skin barrier function is thus also weakened. In addition, other moisturizing factors such as lactate and urea are found to be reduced by up to 70% in the middle and basal layers of the stratum corneum in atopics.

- An important component of the barrier function are ceramides, which consist, among other things, of polyunsaturated omega-6 fatty acids such as linoleic acid and gamma-linolenic acid. These essential long-chain fatty acids are synthesized to a reduced extent in atopics, which also increases the barrier disorder. It is also known that a deficiency of gamma-linolenic acid leads to a reduced synthesis of the anti-inflammatory prostaglandin E1. This results in a lower concentration of cAMP, which can trigger hyperreactivity of the immune system.

In addition to the decreased skin barrier, inflammation is characteristic of AD. Various cells of the skin and the immune system are involved. Allergens can penetrate due to barrier disruption and be presented to T cells via specific IgE receptors in the epidermis. The result is a production of Th2 cells that contributes to inflammation. Further interactions of these inflammatory cells with each other or via messenger substances maintain the chronic inflammation and can, among other things, stimulate B cells to produce IgE antibodies against pollen, dust mites or food. These are found in approximately 80% of affected individuals. Even clinically unaffected skin may permanently exhibit minimal inflammation during AD.

In addition, the reaction of the autonomic nervous system should not be underestimated, which in the case of stress leads to a reduced reactive cAMP increase via inhibition of beta-adrenergic receptors or to itching and a neurogenic inflammatory reaction via mediation of proteases.

Clinic/symptomatology

The pathogenesis of AD then also determines the clinical presentation, which is characterized by dry, red, sensitive and inflamed skin and severe itching. However, differences in expression can be observed in different age groups.

In infancy, the disease usually manifests itself from the third month of life. Approximately 80% of all infant eczema is classified as atopic eczema. The lateral cheeks are affected, and in the course also the extensor extremities such as the elbows, lower and upper thighs, dorsum of the feet, neck, eyelids and hands (Fig. 1). The papulovesicular redness on the hairy head, which changes to firmly adherent, crusty, brownish scales and resembles burnt milk, is extraordinarily typical. This form is therefore also called cradle cap, which, however, is not the same as a milk allergy. In addition, weeping (exudative) inflammations with papules on blurred redness are striking.

Young children (Fig. 2) also show an affection of the extensor sides of the extremities, but also increasingly of the flexures of the joints. Affected children often show scratch marks due to persistent or episodic itching, which additionally leads to sleep disturbances. The scratching itself then causes itching again, creating an itch-scratch cycle. The skin defects caused by scratching also provide an entry point for bacteria and viruses, enabling the risk of superinfection. The most frequent complications are infections with bacteria (especially staphylococci), viruses (mollusca, contagiosa, herpes simplex) and less frequently with fungi (Trichophyton rubrum, Pityrosporum ovale). Infections caused by herpes simplex are associated with a high risk of eczema herpeticatum, generalized infestation of the skin with herpes viruses, and the risk of systemic involvement and require rapid initiation of therapy.

In later childhood and adolescence, the typical flexural eczema with involvement of the large bends of the joints (Fig. 3), but also on the neck and face, especially the eyelid region, the upper chest area and the shoulder girdle, can be found. Itching is the leading symptom here. Areal papular redness appears, which scales. In the flexures and on the neck, the skin is thickened in addition to the inflammatory redness, accompanied by coarsened skin patches and scaling in the sense of lichenification. In addition, erosions and excoriations with hemorrhagic crusting are evident. On the trunk, predominantly areal, confluent, inflammatory-infiltrated foci are found, which may heal hyperpigmented. A special form in childhood and adolescence is pityriasis alba: inflammatory erythema either heals with hypopigmentation or only hypopigmentation occurs, especially in the flexures, without preceding eczema. This form is self-limiting into adulthood with good response to maintenance and mild anti-inflammatory local therapy. Eczema of the scalp is particularly distressing and, in addition to redness, scaling and itching, may also cause temporary hair loss.

In adults, nodular, itchy skin lesions are often present. Other forms of AD at any age manifest as cheilitis, perlèche, pulpitis sicca, vulvar eczema, or chronic hand and foot eczema (Fig. 4).

Diagnostics

The diagnosis of AD is primarily made clinically based on the history and symptoms listed above. To date, there is a lack of laboratory or molecular biologically determinable parameters that can unequivocally prove the diagnosis of AD.

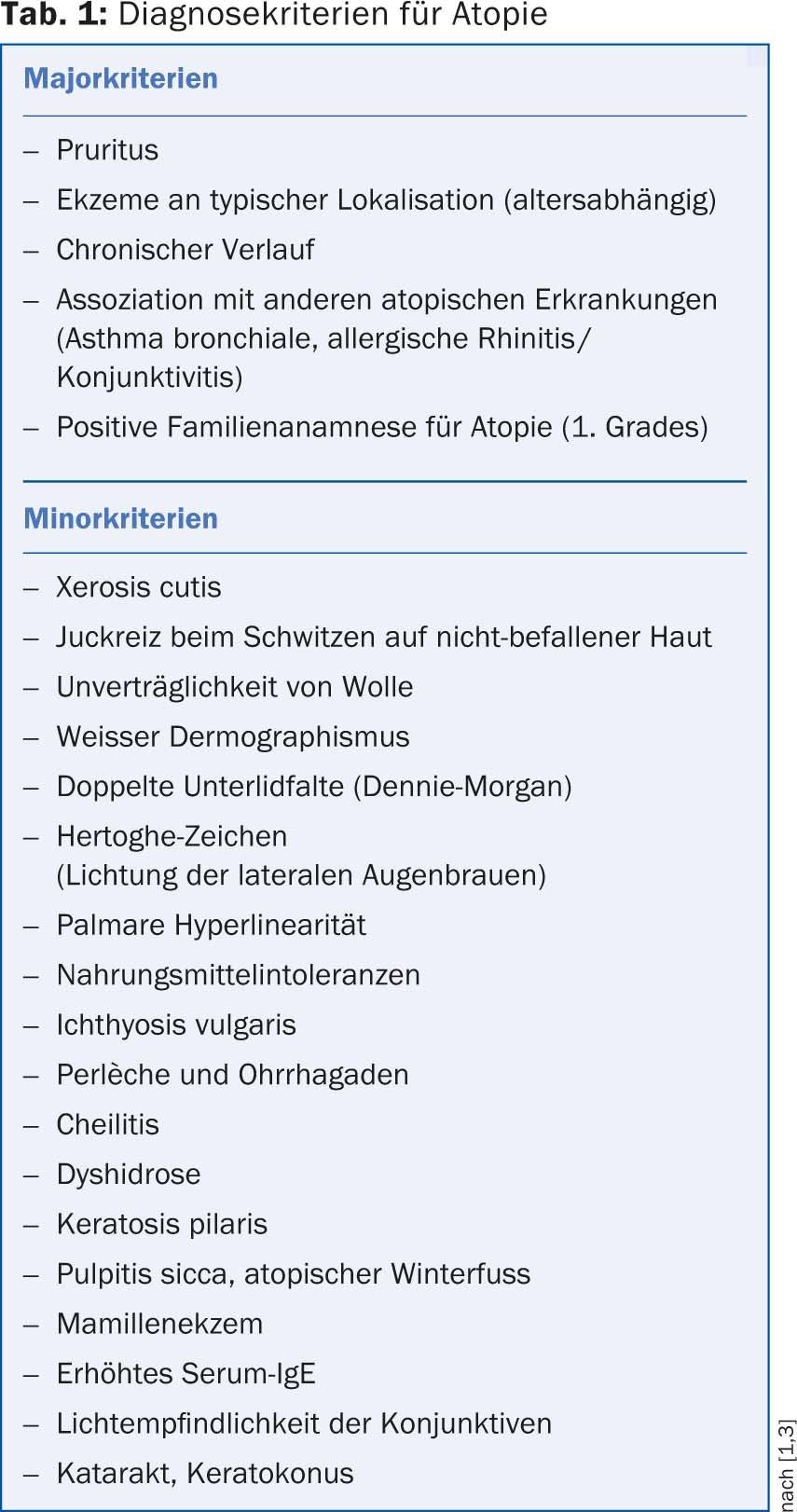

Therefore, the diagnostic criteria for atopy and AD collected by Hanifin and Rajka in 1980 [1] are helpful. Later, these were revised by H.C. Williams [2] and reviewed by Diepgen et al. [3] supplemented. At least three of the major and three of the minor criteria must be fulfilled for the diagnosis to be made (Table 1).

For documentation of progression, it is recommended to record activity parameters of the disease, e.g. by a skin score such as SCORAD.

As complementary laboratory tests, the determination of the total IgE level and the detection of a blood eosinophil may be useful. Furthermore, in case of clinical suspicion of e.g. food intolerances, the determination of specific IgE antibodies is also helpful. The uncritical determination of various possible specific IgE antibodies of e.g. food or aeroallergens without clinical relevance often lead to more uncertainty among the affected persons than to constructive support.

In the future, the microarray method, a determination of a large panel of different allergens, will play a greater role. However, here too, clinical relevance is decisive for the initiation of therapies or, in the case of food, of a diet.

Skin tests are more capable than laboratory tests of detecting relevant sensitization of a person to an allergen. This requires that the test be performed on unaffected skin and that the skin is capable of being tested (i.e., for example, that it is not taking any medication that could affect the ability to test). Only a provocation test can prove whether there is actually a relevant sensitization. And an omission diet when a food allergy is suspected would only be proving when the symptoms subside or even disappear.

Conclusion for practice

- Atopic dermatitis (AD) is diagnosed in the first two years of life in most affected individuals.

- The exact cause of this multifactorial disease is unclear in its completeness, but a combination of external and internal disturbances can be considered certain.

- The pathogenesis determines the clinical appearance: dry, reddened, sensitive as well as inflamed skin and severe itching. Depending on the age group, differences in expression can be observed.

- The diagnosis of AD is primarily made clinically.

Literature:

- Hanifin JM, Rajka G: Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol 1980; 92: 44-47.

- Williams HC, et al: The U.K. working party’s diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis. I. Derivation of a minimum set of discriminators for atopic dermatitis. Br J Derm 1994; 131: 383-396.

- Diepgen TL et al: Development and validation of diagnostic scores for atopic dermatitis incorporating criteria of data quality and practical usefulness. J Clin Epidemiol 1996; 49: 1031-1038.

Further reading:

- Ong PY, et al: Endogenous antimicrobial peptides and skin infections in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1151-1160.

- Palmer CN, et al: Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin area major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet 2006; 38: 441-446.

- Abels C, Proksch E: Therapy of atopic eczema. Dermatologist 2006; 57: 711-725.

- Bieber T: Atopic dermatitis. New Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1483-1494.

- Darsow U, et al: ETFAD/EADV eczema tasc force 2009 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24: 317-328.

- Werfel T, et al: Guideline Neurodermatitis. 2008; http://awmf-online.de

- Dondi A, et al: The switch from non-IgE-associated to IgE-associated atopic dermatitis occurs early in life. Allergy 2013; 68: 259-260.

- De Marco, et al: Foetal exposure to maternal stressful events increases the risk of having asthma and atopic diseases in childhood. Pedatr Allergy Immunol 2012; 23: 724-729.

- Carson CG, et al: Alcohol intake in pregnancy increases the child’s risk of atopic dermatitis. The COPSAC prospective birth cohort study of a high risk population. PLoS one 2012; 7: e42710.