The prevalence of disordered eating and eating disorders in competitive sports is high, reported to be as high as 45% for elite female athletes and 19% for males. Risk factors for the development of an eating disorder in sport can be divided into general, sport-specific, and gender-specific risk factors. In competitive sports, a distinction is made between “classic” eating disorders according to ICD-10 or DSM-5 and sport-specific phenotypes of disordered eating behavior such as anorexia athletica and muscle dysmorphia. Psychiatric comorbidities in the context of disordered eating behavior in sports include psychotic disorders, overtraining syndrome, and sports addiction. The existing scoring system for risk stratification and decision making regarding sports participation, spacing, and “return-to-play” of the Triad Coalition consensus statement should be used in clinical activities.

Disordered eating and eating disorders are found more frequently in athletes than in non-athletes. The prevalence of disordered eating behaviors has been reported to be up to 45% for elite female athletes and up to 19% for males [1].

Sport and level of competition, gender, and age have a critical impact on an athlete’s risk of developing disordered eating behaviors or an eating disorder [1]. Female athletes in aesthetic sports such as rhythmic gymnastics are at particularly high risk for developing an eating disorder [2]. In ball sports and sports where body shape and weight are considered less important, athletes have a lower risk, but it is still higher than in non-athletes [3]. Research on elite Norwegian male and female athletes reported eating disorder prevalence rates of more than 30% for athletes in aesthetic sports and 11% in ball sports [3,4]. Similar results were obtained in studies on elite Australian athletes [5]. In another study of elite French female athletes, the highest presence of eating disorders was found in endurance and aesthetic sports; male athletes were most affected in weight class sports such as wrestling and boxing [6].

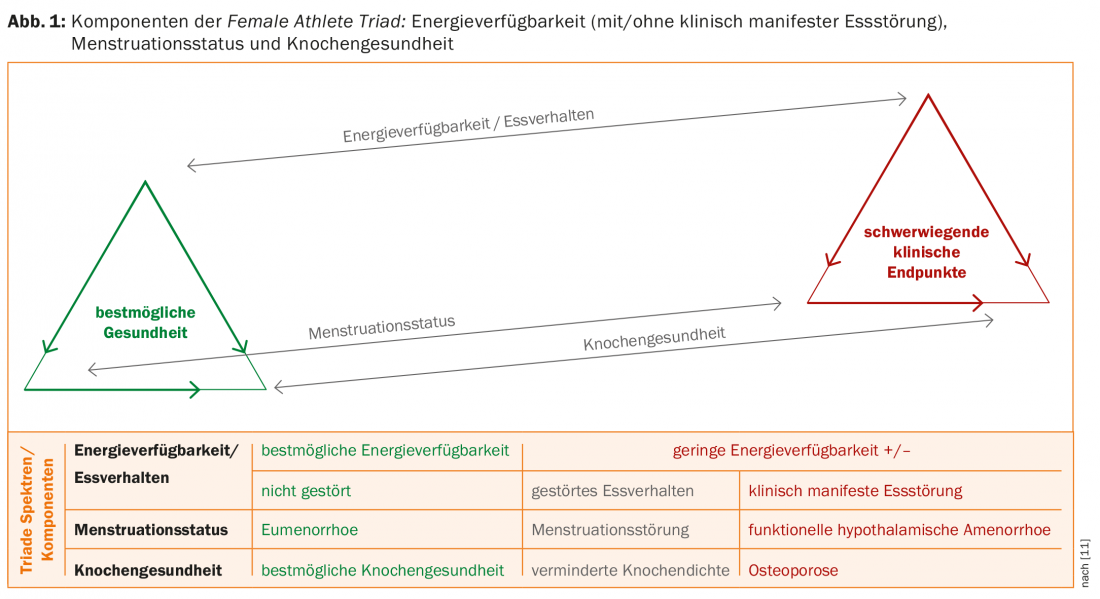

Eating disorders are multifactorial and result from an interaction of biological, social, and psychological vulnerability factors [7,8]. The risk factors for the development of an eating disorder in sport can be divided into general, sport-specific and gender-specific risk factors or into sport-specific and non-sport-specific risk factors (Tab. 1). It is assumed that the increased risk for athletes to develop disordered eating behavior is triggered by the sport-specific risk factors [9]. This assumption is also used in Petrie and Greenleaf’s etiological model [10]. This model incorporates the notion that athletes are subject to two types of pressure. On the one hand, there is pressure in sports to have an ideal body for optimal physical performance, which varies between sports due to different body requirements. On the other hand, there is the Western-influenced social pressure to be slim. The latter affects both athletes and non-athletes, whereas pressures in sport affect only athletes and may explain the higher prevalence of eating disorders in athletes.

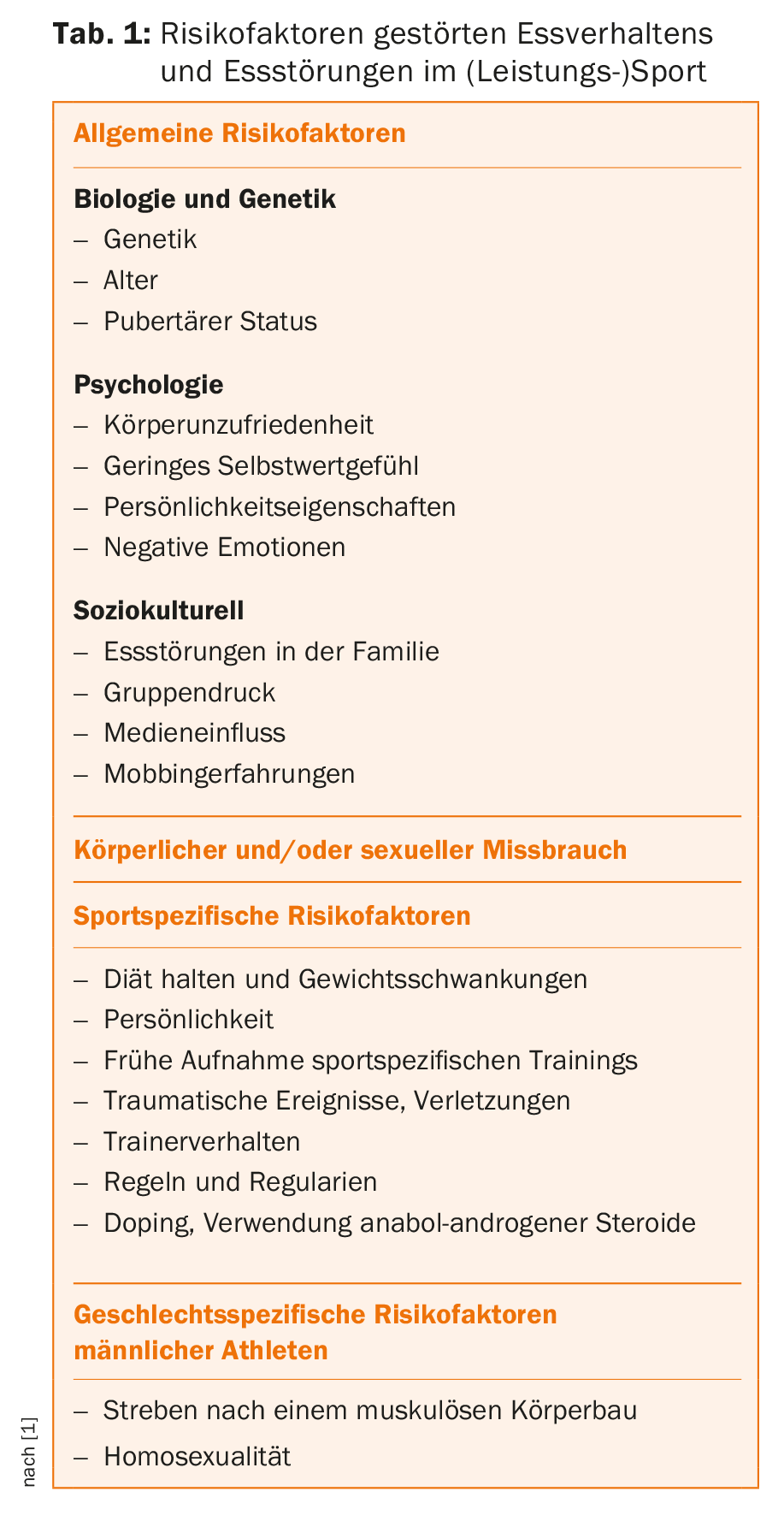

Female Athlete Triad

The Female Athlete Triad, hereafter referred to as the “triad,” refers to the reciprocal relationship of energy availability, menstrual status, and bone health (Fig. 1) [11]. Energy availability has a direct impact on menstrual status, while in turn both energy availability and menstrual status have a direct impact on bone health. The clinical manifestations of the triad and the serious clinical endpoints are low energy availability (with/without clinically manifest eating disorder), functional hypothalamic ammenorrhea, and osteoporosis. Physically active girls and women move at different rates along each component of the triad, depending on food intake and exercise behavior.

Estimates of the prevalence of the three serious triad clinical endpoints in sport range from 0% to 16%; in contrast, estimates of one or two components are much higher, approaching 50% to 60% in certain groups of athletes [12]. In recent studies, the serious clinical endpoints have also been described in adolescent athletes [12]. This is of concern, also in light of the fact that 90% of maximum bone mass is reached by 18 years of age [13], and because adolescents require adequate nutrition and normal hormone function for optimal bone mineralization during this critical developmental period.

Other potential consequences of the triad include endothelial dysfunction associated with cardiovascular effects, stress fractures, and musculoskeletal injuries [12]. Furthermore, a significant impact on physical performance due to persistent low energy availability must be considered, as musculoskeletal injuries disable the athlete and reduce performance in competition. Vanheest et al. [14] report that offspring elite swimmers with menstrual cycle disruption and evidence of low energy availability performed less well compared to their counterparts with normal cycles.

Analogous to the Female Athlete Triad, a Male Athlete Triad has also been described, but has been little studied and receives far less clinical attention, in part because the reproductive system disorders caused by low testosterone are often not recognized [1]. In addition to testosterone status, other components of the Male Athlete Triad include energy availability (and eating patterns) and bone health.

Disturbed eating behavior and eating disorders in competitive sports

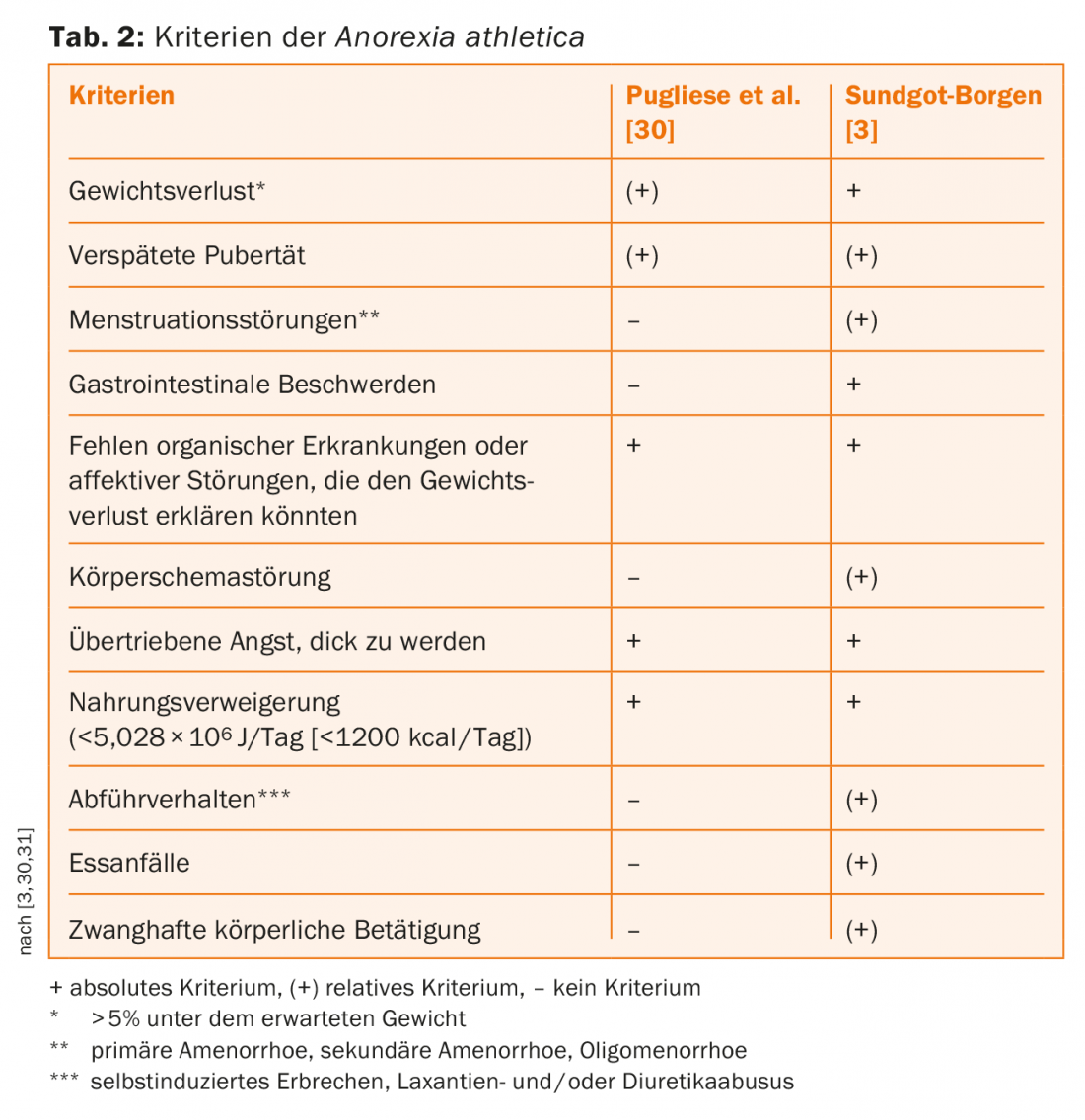

In sport, a distinction can be made between the “classic” eating disorders according to ICD-10 or DSM-5 and sport-specific phenotypes of disturbed eating behavior. Intraindividually, eating disorders generally show a high degree of constancy, but during the course of the disease , alternations between anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and the atypical eating disorders or “Eating Disorders not Otherwise Specified” (EDNOS) occur very frequently [7]. The same is probably true in sports, except that eating disorder phenotypes must be expanded to include those specific to sports. A good model in this context is that of a continuum of disordered eating behavior. Pugliese et al. [30] led in 1983 the Anorexia athletica as a concept of a sports-induced, subclinical eating disorder, which was subsequently further modified by Sundgot-Borgen [3] (Tab.2). The Exercise Bulimia, in which physical activity is used as a compensatory, active measure after a binge eating episode, but also after “normal” eating, by contrast, has so far only been found in sports magazines and Internet forums and corresponds to the description of bulimia nervosa. Therefore, the danger of sport-specific phenotypes is primarily the trivialization and socialization of a clinically manifest and severe disorder of eating behavior. From Pope et al. muscle dysmorphia was introduced in 1993 [15]. Core characteristics are the fear of not being sufficiently muscular and the drive for a muscular and lean physique, with resulting excessive physical activity, changes in dietary behavior, extreme dieting, use of nutritional supplements, abuse of anabolic (-androgenic) steroids and substances [16]. Diagnosed muscle dysmorphia is more common in young adults, and bodybuilders are considered a high-risk group [16]. Whether or not muscle dysmorphia is an eating disorder is controversial. In the DSM-5, it is classified as a body dysmorphic disorder with the specification “with muscle dysmorphia”, but it is not yet mentioned in the ICD. Eating disorder screening and diagnostic tools generally target the pursuit of a lean, non-muscular body and low body weight rather than other markers of low energy availability, such as decreased fat mass and basal metabolic rate. If these limitations of the screening and diagnostic tools are taken into account, the above core features and resulting behaviors are good reasons to consider muscle dysmorphia as an eating disorder. The strong fixation on healthy eating, termed orthorexia by Bratmann in 1997 [17], characterized by an excessive and time-consuming preoccupation with healthy eating, is currently viewed not as a disease but as a health-conscious attitude [18]. Only in extreme cases should the strong fixation on a healthy diet become pathological, with very restrictive diets and avoidance of many foods considered harmful [18]. The prevalence of orthorexia in the general population is reported to be approximately 7% [19]. In a study of over 500 athletes, more than a quarter were found to be orthorectal [20].

For the sake of completeness, the term adipositas athletica should also be briefly introduced here, which describes a sport-specific eating disorder in athletes with large fat mass [21]. Examples can be found in sumo wrestling or open water and long distance swimming. “Binge-eating”, i.e. uncontrolled eating behavior in connection with excessive sport, but also after giving up competitive sport, can be observed increasingly in athletes, although more precise data on this are not yet available in the literature.

Continuum of disordered eating behavior

In the concept of triad, the different eating disorder phenotypes described above can be mapped and understood along the spectrum of energy availability and eating behaviors [11] and/or a continuum. This continuum of disordered eating behavior begins with healthy orthorectal dieting, reduction of energy intake and successive weight loss, then progresses to restrictive dieting, chronic dieting, frequent weight fluctuations, fasting, passive dehydration such as saunas and hot baths, active dehydration such as wearing tracksuits during exercise. The “classic” eating disorders anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa then represent the end of this continuum of disordered eating behavior.

Psychiatric comorbidities

Eating disorders are often accompanied by other mental disorders, Axis I disorders (general psychiatric disorders), depression, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders, but also Axis II disorders (personality disorders) are common and can have a decisive influence on the course of the eating disorder and must be included in the treatment [22,23]. Psychiatric comorbidities that need to be considered in the context of disordered eating behavior in sports (cf. Overview [24]): Psychotic disorders are rare in sports, but they are of great importance in the context of muscle dysmorphia and the use of anabolic androgenic steroids and must be taken into account. Overtraining syndrome, defined as loss of performance with or without physiological and psychological signs, after excessive and prolonged training and sports addiction have the greatest importance as comorbidities. While primary sports addiction is rare, the secondary type is common and then occurs as a comorbidity of a mental illness, typically an eating disorder. It is important to consider any additional sports addiction that may exist in athletes with an eating disorder, as treatment of only the eating disorder may lead to symptom increase of the eating disorder if the sports addiction is not recognized, and conversely, treatment of only the sports addiction may also lead to symptom increase of the eating disorder. In studies of athletes, the prevalence of sports addiction has been reported as 3 to 4.5% [25]. Other comorbidities that could be relevant in the context of disturbed eating behavior in sports are attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and delirium . Hypernatremia, hyperthermia, or heat stroke may be causes of acute delirium, which can occur particularly in endurance athletes.

Statements and position papers

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) [9], the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) [11], and the American National Athletic Trainers Association (NATA) [26] have issued position statements and position papers on disordered eating and eating disorders in competitive sports over the past decade. The ACSM and IOC position papers address the Female Athlete Triad; the NATA position paper addresses disordered eating behaviors and eating disorders in female and male athletes. A significant limitation of these papers is or was that, with the exception of the NATA paper that also targeted male athletes, they only targeted female athletes. Another limitation of these papers is that none of them formulated recommendations on the conditions under which affected athletes would be allowed to resume their sport; that is, the criteria for a “Return-To-Play” (RTP) were missing.

Through the consensus statement of the Female Athlete Triad Coalition [27] and the update of the IOC statement [28], also published in 2014, the above-mentioned restrictions were partially reduced. The Triad Coalition Consensus Statement [27] was intended to both complement the 2007 revised ACSM statement [11] and provide clinical guidelines to physicians, trainers, and other health care providers regarding screening, diagnosis, and treatment of the triad. And, unlike previous papers, the consensus statement now included clear RTP recommendations.

The authors of the consensus statement propose a scoring system for risk stratification that takes into account the extent of risk and is intended to assist physicians in making decisions regarding sports participation, spacing, and RTP.

The 2014 update to the IOC statement [28] also provides guidelines on risk assessment, treatment, and RTP. There, a more comprehensive name for the condition known as Female Athlete Triad is proposed: the new name “Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport” (RED-S) is intended to reflect both the complexity of this condition and the fact that male athletes may also be affected. The new designation has been the subject of controversy ever since. The main criticism of the new designation is that it is not sufficiently supported scientifically [29]. Above, therefore, the concept of triad, which has more than 30 years of published evidence, was used and RED-S was not discussed further. Accordingly, the content of this article is guided by the ACSM Statement [11] and Triad Coalition Consensus Statement [27].

Prevention, screening, diagnosis and treatment

For the prevention and early intervention of disordered eating in competitive sports, appropriate education of athletes as well as parents, coaches, trainers, judges and officials is important.

Athletes should be tested for the triad, or disordered eating behavior and its physical consequences, during sports physical fitness examinations and/or annual health examinations. This screening should include questions covering all aspects of the triad, followed by a more in-depth examination looking at: impaired eating patterns, physical consequences of decreased energy availability, any reproductive system disorders, and bone demineralization. Recognition of any of these components of the triad, as well as unexplained or common musculoskeletal injuries or stress fractures, should prompt further investigation that includes the other components of the triad.

Screening with subsequent diagnosis depends on careful questioning and examination by a physician, usually the primary care physician or a general practitioner and/or a sports physician, and by other members of a multidisciplinary treatment team. Such a team includes a sports nutritionist, exercise physiologists, and psychiatrists and psychotherapists who specialize in the field of eating disorders. Coaches, parents, and other family members can provide meaningful support to the treatment team. Specialists such as gynecologists, endocrinologists, and rheumatologists should be consulted if the treating physician does not have the appropriate sufficient experience and skills in the diagnosis and treatment of the individual triad components.

Each member of this multidisciplinary treatment team must establish a sustainable and trusting therapeutic relationship with the athlete, the process consisting of “screening → diagnosis → risk stratification → treatment → Return-To-Play”, is persistent and challenging, especially when there is a clinically manifest eating disorder and a decision needs to be made regarding participation, spacing, and Return-To-Play must be taken. The athlete’s environment, parents, coaches, trainers, and other key others must be involved in this process from the beginning, and possibly teammates at certain points. In the end, however, the decisive factor is the honesty and willingness of the athlete to participate in each and every point of the above process.

The first goal of treating each Triad component, or the physical consequences of low energy availability, is to increase energy availability by increasing dietary energy intake and/or reducing energy expenditure through exercise. Nutritional counseling and monitoring are sufficient interventions for many athletes, disordered eating behavior possibly, a clinically manifest eating disorder certainly, but requires appropriate psychiatric-psychotherapeutic treatment.

Risk Stratification and Return-To-Play

In the Triad Coalition consensus statement [27], as a supplement to the ACSM statement published in 2007, the authors propose a scoring system for risk stratification that takes into account the extent of risk and is intended to assist physicians in making decisions regarding sports participation, spacing, and return-to-play. This model is very well suited for clinical use and should be used during any sports medical examination of an athlete.

Special consultation for sports psychiatry and psychotherapy

As the first specialized offer for competitive athletes with psychiatric problems and illnesses in Switzerland, there is a special consultation hour for sports psychiatry and psychotherapy at the Clinic for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics of the Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich and at the Center for Eating Disorders of the University Hospital Zurich [24]. One focus of this new service is on eating disorders and sports addiction . However, this new service is also intended to provide counseling and treatment for other psychological problems and illnesses affecting competitive athletes.

Literature:

- Bratland-Sanda S, et al: Eating disorders in athletes: overview of prevalence, risk factors and recommendations for prevention and treatment. European journal of sport science 2013; 13(5): 499-508.

- Thompson RA, et al: Eating disorders in sport.1st ed. New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Sundgot-Borgen J: Prevalence of eating disorders in elite female athletes. Int J Sport Nutr 1993; 3(1): 29-40.

- Sundgot-Borgen J, et al: Prevalence of eating disorders in elite athletes is higher than in the general population. Clin J Sport Med 2004; 14(1): 25-32.

- Byrne S, et al: Elite athletes: effects of the pressure to be thin. J Sci Med Sport 2002; 5(2): 80-94.

- Schaal K, et al: Psychological balance in high level athletes: gender-based differences and sport-specific patterns. PLoS One 2011; 6(5): e19007.

- Fairburn CG, et al: Eating disorders. Lancet 2003; 361(9355): 407-416.

- Treasure J, et al: Eating disorders. Lancet 2010; 375(9714): 583-593.

- IOC Medical Commission Working Group Women in Sport. Position Stands – Female Athlete Triad Coalition [cited 2016 Aug 25]. Available from: www.femaleathletetriad.org/for-professionals/position-stands/#title2.

- Tenenbaum G, et al: Handbook of sport psychology.3rd ed. Wiley Online Library, 2007.

- Nattiv A, et al: American College of Sports Medicine position stand. The female athlete triad. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 2007; 39(10): 1867-1882.

- Barrack MT, et al: Update on the female athlete triad. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine 2013; 6(2): 195-204.

- Matkovic V, et al.: Timing of peak bone mass in Caucasian females and its implication for the prevention of osteoporosis. Inference from a cross-sectional model. J Clin Invest 1994; 93(2): 799-808.

- Vanheest JL, Rodgers CD, Mahoney CE, Souza MJ de: Ovarian suppression impairs sport performance in junior elite female swimmers. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 2014; 46(1): 156-166.

- Pope HG, et al: Anorexia nervosa and “reverse anorexia” among 108 male bodybuilders. Compr Psychiatry 1993; 34(6): 406-409.

- Suffolk MT, et al: Muscle dysmorphia: methodological issues, implications for research. Eat Disord 2013; 21(5): 437-457.

- Bratman S: Health Food Junkie – Orthorexia Nervosa, the New Eating Disorder [cited 2016 Aug 25]. Available from: www.beyondveg.com/bratman-s/hfj/hf-junkie-1a.shtml.

- Barthels F, et al: Orthorectic eating behavior – nosology and prevalence rates. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2012; 62(12): 445-449.

- Varga M, et al: Evidence and gaps in the literature on orthorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord 2013; 18(2): 103-111.

- Segura-Garcia C, et al: Orthorexia nervosa: a frequent eating disordered behavior in athletes. Eat Weight Disord 2012; 17(4): e226-e233.

- Berglund L, et al: Obesity athletica: a group of neglected conditions associated with medical risks. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2011; 21(5): 617-624.

- Herpertz S, et al: Handbook of eating disorders and obesity. 2nd ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer (Online), 2015.

- Möller H-J, et al: Psychiatry, psychosomatics, psychotherapy. 4th ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2011.

- Claussen MC, et al: Sports psychiatry and sports psychotherapy: psychological problems and disorders in competitive sports. Swiss Medical Forum 2015; 15(45): 1044-1049.

- Ziemainz H, et al: The risk for sports addiction in endurance sports. Dtsch Z Sportmed 2013; 64(2): 57-64. doi: 10.5960/dzsm.2012.057.

- Bonci CM, et al: National athletic trainers’ association position statement: preventing, detecting, and managing disordered eating in athletes. J Athl Train 2008; 43(1): 80-108.

- Joy E, et al: 2014 female athlete triad coalition consensus statement on treatment and return to play of the female athlete triad. Curr Sports Med Rep 2014; 13(4): 219-232.

- Mountjoy M, et al: The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female Athlete Triad – Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). Br J Sports Med 2014; 48(7): 491-497.

- Souza MJ de, et al: Misunderstanding the female athlete triad: refuting the IOC consensus statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). Br J Sports Med 2014; 48(20): 1461-1465.

- Pugliese MT, et al: Fear of obesity. A cause of short stature and delayed puberty. N Engl J Med 1983; 309(9): 513-518.

- Herpertz-Dahlmann B, et al: Competitive sports and eating disorders from a child and adolescent psychiatric perspective. Monatsschrift Kinderheilkunde 2000; 148(5): 462-468.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(6): 22-28.