Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver cell tumor and presents a challenge in systemic treatment with its intrinsic resistance to classical chemotherapeutic agents. The responsible clinician must not only assess the tumor situation with a possible therapeutic effect – rather, a careful balancing of treatment benefits and the risk of hepatic decompensation is required.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver cell tumor and presents a challenge in systemic treatment with its intrinsic resistance to classical chemotherapeutic agents [1]. In addition to the numerically limited therapeutic options in systemic treatment to date, advanced liver disease is also predominantly critical for prognosis. Not only the known risk factors for liver cirrhosis such as viral hepatitis HBV or HCV but also alcohol play a role. Sometimes fatty liver, which is on the increase in our region, as well as non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFLD) is not only a risk factor of HCC. Rather, the reduced liver performance associated with this is also a prognostic factor in HCC treatment [2]. Thus, the responsible clinician must not only assess the tumor situation with a potential therapeutic effect – rather, a careful balancing of treatment benefits and the risk of hepatic decompensation is required. Curative treatments are reserved for early stage HCC using the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging for BCLC 0/A and include surgery, local ablative techniques, or liver transplantation. The risk of recurrence after surgery or ablation in the pre-damaged liver is quite high at 65-85% depending on studies and it is in this situation that different treatment options are currently being investigated in clinically controlled trials [3]. For patients in “intermediate” or “advanced” HCC, the treatment guideline is palliative. Transarterial radioembolization (TARE) is an application that is often used for BCLC-B stage. Here, too, there is a high risk of recurrence or the development of de novo HCC foci in the pre-damaged liver. Thus, this therapeutic area with preserved good liver function is also a current field of interest of adjuvant systemic treatments. After the very limited choice of system options for HCC in BCLC-C for a long time with the multikinase inhibitors (MKI) sorafenib in the first line [4] and regorafenib in the second line [5], treatments for HCC also expanded in the last 3.5 years with combination therapies of vascular antibodies plus immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) ([6,7]. Additionally, in the field of “advanced” HCC (aHCC), there is currently a flurry of study interest in additional combinations, sometimes MKI plus ICI. These results are eagerly awaited, as not only are such combinations being investigated in first-line treatment, but also some therapeutic combinations are being used after prior immunotherapy. As early as late 2021, a combination of cabozantinib plus atezolizumab in first-line aHCC was demonstrated at the virtual ESMO Asia Symposium with the COSMIC-312 trial. In early 2022, a positive trial with an ICI combination had been presented at the virtual ASCO GI Symposium with the HIMALAYA trial. I would like to present these data as well as the further study prospects for combination therapies in a simplified overview.

Combination therapies in aHCC

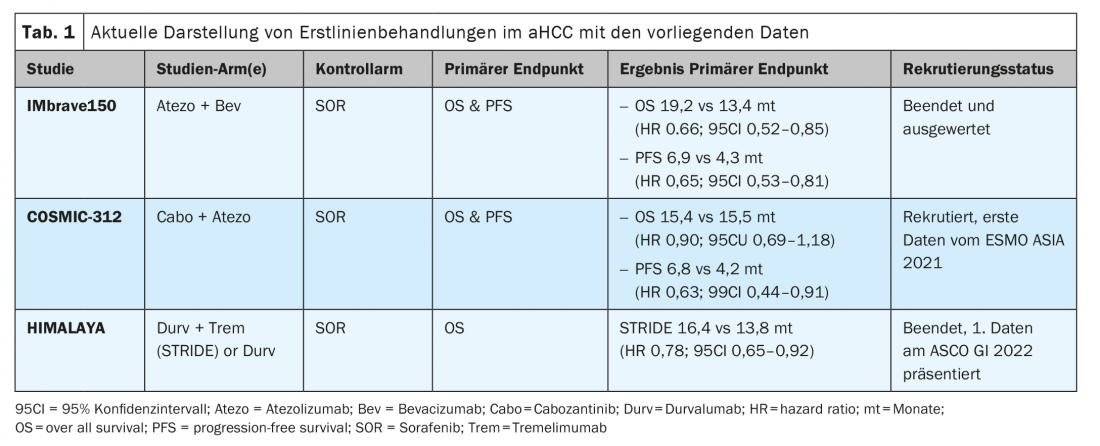

IMbrave 150 trial – further long-term results from ASCO 2021: The IMbrave-150 trial achieved a global new standard of care in first-line treatment of aHCC in BCLC C as well as with early use in BCLC B stage starting in 2019. [7] Less than a year later, on November 16, 2020, SwissMedic also granted approval to this combination in the first-line treatment of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in Switzerland. This combination achieved significant improvement in mOS and mPFS compared with sorafenib. At the virtual ASCO GI 2021, the current data with longer follow-up intervals were presented [8]. The pre-established significant survival benefits in mOS (19.2 vs 13.4 months; HR 0.66; p=0.0009) and also mPFS (6.9 vs 4.3 months; HR 0.65; p=0.0001) were confirmed over the longer observation period of more than 18 months. The risk reduction in death rate of 34% and overall survival benefit of 5.8 months over sorafenib have also been achieved in addition with improvement and stabilization in quality of life [6,9].

COSMIC-312 Study – Findings from ESMO Asia 2021: Additional and interesting combinations consist of multikinase inhibitors (MKI) and checkpoint inhibitors (ICI). Sorafenib, cabozantinib, or lenvatinib in combination with PD-1 inhibitors are currently under evaluation in trial arms in aHCC. Here, the COSMIC-312 trial (NCT03755791) has been designed into 3 arms for first-line treatment of aHCC. It is interesting to note that BCLC-B stages can already be included. Against the standard arm sorafenib, one study arm will be compared with cabozantinib monotherapy (Cabo) and another study arm will be compared with the combination of cabozantinib plus atezolizumab (Cabo-Atezo) for the dual endpoint of mOS and PFS. Initial study results from 837 randomized patients in the global trial were demonstrated at ESMO Asia 2021 [10]. The Cabo-Atezo group met the PFS endpoint versus sorafenib, but there was no difference in overall survival in the two arms of identical curve progression (Table 1) . The PFS data of Cabo Mono were also significantly superior to sorafenib, but OS data have not yet been demonstrated. Interestingly, hepatitis B (HBV)-associated HCC in particular benefited from the Cabo-Atezo combination with a PFS HR 0.49 (95% CI 0.29-0.73). This HBV subgroup achieved an OS benefit with an HR of 0.53 (95% CI 0.33-0.87). Also, extrahepatic involvement (EHD) and or macrovascular invasion (MVI) suggested a PFS benefit for Cabo-Atezo combination therapy in the subgroup analysis (HR 0.57; 95% CI 0.41-0.78). In contrast, non-viral associated HCC and or hepatitis C (HCV) associated HCC do not appear to benefit from the combination. Notably, Asians benefited more from the combination than non-Asian HCC patients, so it remains unclear whether HBV infection or ethnicity is a confounder in the analysis. The authors cautiously concluded that the combination represents a new option in the treatment of HCC. However, the final analyses should be awaited.

ORIENT-32 – Data from ESMO 2021: At ESMO 2021, the results of the ORIENT-32 trial, another combination with sintilimab (Sin) and bevacizumab (Bev) versus sorafenib were demonstrated [11]. In the Chinese-only population, the Sin + Bev combination demonstrated significant treatment benefits in terms of OS (NR vs 10.4 months) and mPFS (4.6 vs 2.8 months). The side effect rates of IMbrave and ORIENT-32 were lower compared with sorafenib and were consistent with the typical aVGFR and IO side effect profile.

HIMALAYA trial – combination immune checkpoint inhibitors in first-line aHCC: ICI combination therapies are also being studied more extensively in aHCC. For example, the combination of nivolumab plus tremelimumab (Trem) was already approved by the FDA in 2019 in aHCC after prior sorafenib therapy. Another ICI combination approved by the FDA since January 2021 is devaruzumab plus tremelimumab. Both combinations are applicable in second-line therapy but are not supported by EMA or Swissmedic. Now, the HIMALAYA trial (NCT03298451) was recently presented at ASCO GI 2022 with preliminary data. The now 3-arm trial of STRIDE arm (tremelimumab plus durvalumab) or durvalumab mono (Durv) was compared versus sorafenib as the standard arm. The primary endpoint OS was significantly superior in the STRIDE arm of 16.4 months compared to the sorafenib arm of 13.8 months, which was also very good (HR 0.78; p=0.0035). Differences in PFS were not present, but an impressive median DoR (duration of response) of 22.34 months and a 65.8% patient population with a Trem+Durv response at the 12-month time point, respectively, was present. These results are very interesting for the checkpoint inhibitor combination, and in the previous subgroup analyses, almost every single group supported the use of this combination. The great debate of the appropriate population versus the new SoC (standard of care) atezolizumab plus bevacizumab is given and not easily answered. In my view, there is a lack of clear biomarkers for selection or assignment to one of the two combinations.

Studies currently recruiting and expected in the near future.

CheckMate 9DW: This phase 3 NCT04039607 trial is comparing the combination of nivolumab (Nivo) plus ipilimumab (Ipi) versus sorafenib in the first-line setting in planned 728 aHCC BCLC-B and BCLC-C stages. The primary endpoint is OS and the study is currently open but not currently recruiting due to the COVID-19 pandemic (as of January 28, 2022 clinicaltrials.gov).

LEAP-002: This phase 3 trial (NCT03713593) is comparing the SoC lenvatinib versus the combination lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab. The primary outcome compared will be PFS as well as OS of both groups. This study is also active, but recruitment is not currently taking place (as of December 28, 2021 clinicaltrials.gov).

Adjuvant recruiting studies

Not only is the field of aHCC currently under intense investigation for an effect of immunotherapies, but also the local stages after surgery or ablation are being studied. A placebo therapy is set as the control group in each case. In this regard, pembrolizumab is being investigated as monotherapy in the Keynote-937 trial (NCT03867084), toripalimab in the JUPITER-04 trial (NCT03859128), or nivolumab in CheckMate 9Dx (NCT03383458) as adjuvant therapy. The EMERALD-2 trial (NCT03847428) focused on durvalumab or the combination of durvalumab plus bevacizumab in the adjuvant setup. The ImBrave050 trial (NCT04102098) is also evaluating the combination of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in high-risk HCC patients versus placebo after surgery or ablation. These results are eagerly awaited overall as positive study results shift the use of ICI into an early line. Thus, in the future, not only an expansion of ICI with different combinations in aHCC will result in an intensified discussion of placement in the guidelines, but also the sequence in the case of recurrence after surgery or ablation, if ICI was applied in this case.

Outlook and “unmet needs

The studies presented are eagerly awaited in both locally and locally advanced BCLC-B stages of HCC and will set a new standard of care if endpoints are met. Also, in the aHCC with BCLC B or C stages, many study outlooks are currently expected with positive signals. Thus, we can hope for a variety of new therapeutic combinations in the near future. In addition to these positive outlooks, there are also direct and indirect issues with currently (still) unresolved requirements. This refers on the one hand to the optimal therapy sequence of an HCC patient and also to the question of different therapies depending on the underlying hepatopathy. In contrast, the question of suitable biomarkers for prognosis and prediction is still unsatisfactorily solved and is also a point of current research questions. In particular, the analysis of instrinsic or acquired resistance to ICI (immune checkpoint inhibition) therapy plays a central role. For clinical use, the safety and efficacy of the therapies in CHILD-Pugh B patients as well as post-transplant patients also play a role, as this was not included in the previous studies. From these open questions arises the need for the development and definition of clinical and diagnostic scores to select the optimal patients for the best possible combination therapy.

Take-Home Messages

- The treatment field within BCLC stage C HCC have expanded greatly, including a combination of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab currently approved in Switzerland.

- Liver function and a good Child-Pugh score is critical for the use of systemic therapies in HCC.

- Patients with HCC should be evaluated jointly by a hepatologist and medical oncologist at an early stage so that an assessment for systemic therapy is also given for liver function.

- The treatment field of HCC is also expanding in the early BCLC stages. When possible, patients should be included in studies.

Literature:

- Fulgenzi CAM, et al; Immunotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2021, 22(10): 87.

- Galati G, et al: Current Treatment Options for HCC: From Pharmacokinetics to Efficacy and Adverse Events in Liver Cirrhosis. Curr Drug Metab 2020, 21(11): 866-884.

- Llovet JM, et al: Locoregional therapies in the era of molecular and immune treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18(5): 293-313.

- Llovet JM, et al: Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008, 359(4): 378-390.

- Bruix J, et al: Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 389(10064): 56-66.

- Casak SJ, et al: FDA Approval Summary: Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab for the Treatment of Patients with Advanced Unresectable or Metastatic Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2021. 27(7): 1836-1841.

- Finn RS, et al: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2020, 382(20): 1894-1905.

- Finn R, QS, Ikeda M, et al: IMbrave150: updated overall survival data from a global, randomized, open-label phase III study of atezolizumab + bevacizumab vs sorafenib in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 39, no. 3_suppl (January 20, 2021) 267-267, 2021.

- Gordan JD, et al: Systemic Therapy for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38(36): 4317-4345.

- Kelley RK, et al: VP10-2021: Cabozantinib (C) plus atezolizumab (A) versus sorafenib (S) as first-line systemic treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC): Results from the randomized phase III COSMIC-312 trial. Annals of Oncology 2021. ESMO VIRTUAL PLENARY ABSTRACT VOLUME 33, ISSUE 1, P114-116.

- Ren Z, et al: Sintilimab plus a bevacizumab biosimilar (IBI305) versus sorafenib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (ORIENT-32): a randomised, open-label, phase 2-3 study. Lancet Oncol 2021, 22(7): 977-990.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2022; 10(2): 6-8.