The physician can only grasp a patient’s unique experience of illness through a human encounter with the patient. By actively listening and asking questions, even the consultation has a therapeutic effect.

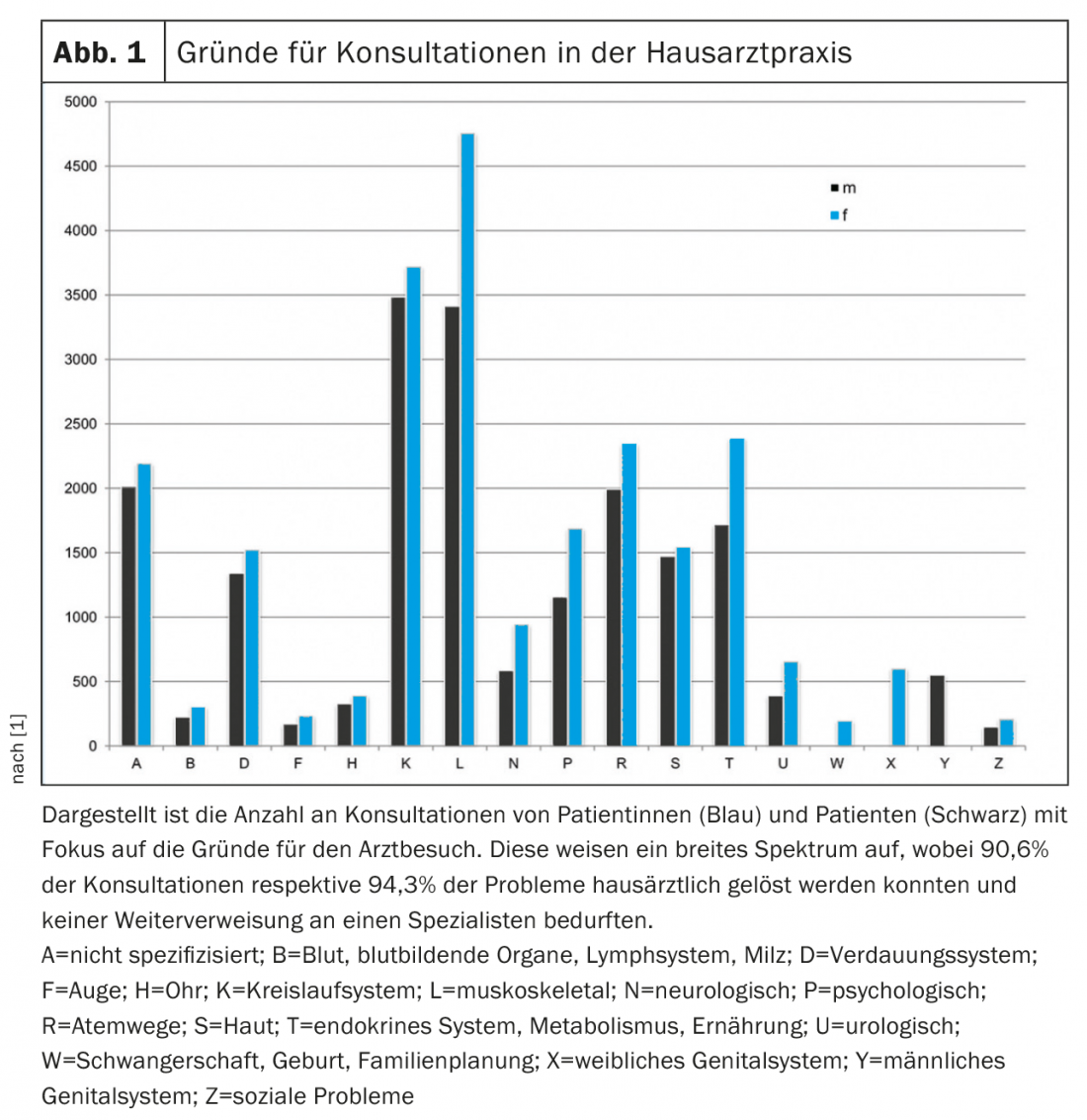

Outstanding medical-technological achievements in recent decades have contributed to the fact that we can diagnose and treat diseases as never before, even in our family practices. In addition to our excellent training and continuing education, these contribute to the fact that in Switzerland we are able to solve 94.3% of complaints by general practitioners and only have to refer 5.6% [1]. (Fig. 1). Philippe Luchsinger, MD, President of the Professional Association of Family Physicians and Pediatricians Switzerland (mfe), proudly titles his focus article in the association’s newsletter “Standpunkte” “Family Physicians and Pediatricians – the “Prescription for a Healthy Switzerland” [2]. And indeed, family medicine makes an efficient, high-quality and cost-effective contribution to our healthcare system, which was named the best healthcare system in Europe by the Health Consumer Index 2018 [3].

Focus on people

The majority of the impact of family medicine comes not from the technology available, but from its targeted use according to the needs of the patient. Even in a modern, technically well-equipped family practice, people are at the center of everything. The family doctor does not see him simply as a carrier of a disease to be analyzed and treated in him, but encounters him as an autonomous and self-responsible person in the context of his life, with his unique being healthy and sick, with his values, specific needs, goals and resources.

Before the doctor reaches for her modern arsenal of technical means, she devotes herself to the patient as a human being in the consultation. In conversation, both build rapport and mutual trust. They meet each other on an equal footing: the patient as an expert with knowledge about his symptom/problem and his individual experience of illness, the doctor as an expert with knowledge about the medical context and possibilities. These are indispensable basics for every therapeutic process with and without modern technical possibilities.

Creating a shared reality

The patient is confused by a symptom that he perceives and cannot classify. He looks for solutions himself, informs himself here and there, also with “Dr. Google”. In this way, he creates an inner picture of what he senses. An image that can turn out quite surreal or mystical without precise knowledge of anatomy and physiology: “My cervical vertebra is displaced” or “A thorn is in my back”. The patient constructs his individual reality. He usually frames these in a catastrophizing way, often creating a “worst case” scenario (“Is it cancer, perhaps?”). Uncertainty and worry ultimately lead him to the doctor; in fact, in the “International Classification of Primary Care, 2nd Edition” (ICPC-2), “fear of…” is its own diagnosis.

In the consultation, the patient describes what she perceives. The physician transforms their symptom into a biochemical, pathophysiological picture using their medical knowledge. He creates his abstract medical reality.

With his questions, the doctor probes the patient’s personal construction of reality. Together they create a shared reality. From here, they decide on the necessary and possible further investigations in a goal- and solution-oriented manner. They create a mutually acceptable “assessment” and decide on a therapeutic process. Uncertainties associated with any decision are also dealt with jointly, as is success or failure.

Actively listen and ask the right questions

The doctor listens to the patient actively and empathically. It takes in factual information about obtaining a medical diagnosis, but also considers the emotional component behind the facts. He wants to understand the human being as a whole.

With her questions, the doctor wants to dig deeper into medically relevant information. In addition, she wants to use them to actively involve the patient in the process, to encourage her to think about the origin of her symptom or problem – about its connections and interactions with her living environment, its effects on her family, professional and social environment. By following up, she has the patient explain exactly what is meant. In this way, she triggers further reflection in the patient about her being ill and her experience of illness, about the meaning she gives to her illness, and about ways of seeing “things” with a broader view.

Together they create orientation and explore expectations and goals the patient is striving for. They match these expectations with medical possibilities and necessities and look for solutions. And they do not forget to distribute the tasks and clarify what the doctor’s job is.

Dealing with uncertainty and fear

Uncertainty/uncertainty and uncertainty/fear always play a role for both the patient and the physician. They permeate everything we do and don’t do. The patient feels that his vital existence is at risk; the physician is concerned not to miss anything, but to understand the symptom correctly and to advise the patient regarding the best possible examination and therapy. Paying attention to uncertainty/uncertainty, addressing it, and giving it the space it needs is central to successful treatment.

For example, a 40-year-old patient being treated for mild hypertension complains in the consultation about a recurrent stabbing sensation in the left chest. The doctor interviews him using the ICE questions (“Ideas, Concerns, Expectations”) to find out what he thinks and fears based on his reality construction. It turns out that the patient had come across the diagnosis of heart attack during a Google search, which made him very frightened and led him to the consultation. Further history reveals that the punctate stinging occurs occasionally and for seconds, never during physical exertion. The patient can also describe what else is currently moving him in his life. After situationally appropriate medical information about the characteristics of heart pain, the physician and patient realize that the twinge has nothing to do with the heart, but with the chest wall. Discussion of the risk profile for coronary artery disease draws a very favorable result. The patient cannot improve anything in his all-around healthy lifestyle. Nothing more can be done preventively against a heart attack in this situation than to continue to treat the blood pressure reliably. A minimal residual risk of sudden cardiac death remains, as it does for all people. Life ultimately remains fraught with uncertainty. Doctor and patient create a shared reality. Both consider an electrocardiogram unnecessary. A 24-hour blood pressure measurement that had previously, although agreed, not been taken on several occasions is now to take place. It should prove whether the current drug therapy of hypertension, with its practice hypertension component, has a sufficiently good blood pressure-lowering effect in everyday life, and in particular whether it also brings about a sufficient night-time reduction in blood pressure. The patient feels understood, the doctor is sure that she has correctly assessed the situation together with the patient and that they are following an appropriate therapeutic path. Doctor and patient are satisfied.

Of course, there is also the reverse case. Overriding the patient’s experience of illness with its often catastrophizing construction of reality and basing further action only on the physician’s reality can easily lead down medical wrong paths, even with a “clear” diagnosis.

An example: the same patient would come to the consultation and would be concerned about his stinging in the left chest. He would not be asked about his reality construction. The doctor would speak of chest wall pain without explanation. The patient would remain stubbornly unsettled. They wrote an ECG for safety and also drew blood to determine troponin. The ECG showed partial right bundle branch block, which also occurs in cardiac healthy subjects. Uncertainty would remain with the patient and the physician. The next step, to be on the safe side, was echocardiography and ergometry with the expectation that these measures would provide definitive clarity. However, they again showed a small change that should be further clarified by coronarography or cardiac computed tomography to be completely sure. A medical-technical “nightmare” could be the result.

The consultation as a modern instrument with therapeutic effect

The consultation is the oldest “treatment tool” of the physician and it remains the most efficient instrument even in a modern (family) doctor’s office equipped with all medical-technical possibilities. A consultation carefully designed by the doctor in a person- and solution-centered way develops its own therapeutic effect. In the consultation, the doctor and the patient find a path of high quality focused on the needs of the patient. They find out what is necessary for the patient to achieve wellness according to their needs. They discuss what he himself can contribute. They decide which medical-technical resources they want to use specifically, whether and what other assistance is needed.

In the consultation, the doctor and patient pause reflectively. They weigh every step in investigation and therapy before they take it. This allows them to “stay on track,” doing what is necessary and refraining from what is unnecessary. A consultation designed in this way is helpful for the patient, makes the attending physician happy, and keeps both of them healthy [4,5].

Take-Home Messages

- The physician can only grasp a patient’s unique experience of illness through a human encounter with the patient. By actively listening and asking questions, even the consultation has a therapeutic effect.

- In the interplay of relationship and technology, doctor and patient work together to develop appropriate, person-centered, efficient, high-quality medicine.

- The basis for this is mutual trust and an encounter at eye level: the patient is an expert on his or her individual experience of illness, while the physician knows the medical context and treatment options.

Literature:

- Tadjung R, et al: Referral rates in Swiss primary care with a special emphasis on reasons for encounter. Swiss Med Wkly 2015; 145: w14244.

- Luchsinger, Philippe: Family physicians and pediatricians. The recipe for a healthy Switzerland. Why it pays to invest in family medicine. Viewpoints 2018; 2: 4-6.

- Health Consumer Powerhouse: Euro Health Consumer Index 2018. https://healthpowerhouse.com/media/EHCI-2018/EHCI-2018-report.pdf, last accessed 03/13/2019.

- Bircher L, Kissling B: “I imagine a medicine …”. Correspondence between a young female physician and an experienced family physician. Zurich: rüffer & rub, 2018.

- Kissling B, Ryser P: The medical consultation. Systemic solution-oriented. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, to be published in fall 2019.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(4): 5-7