Patients with rheumatic diseases often suffer from severe pain. In addition to treating the underlying condition, management of this pain is essential to prevent chronicity or even disability.

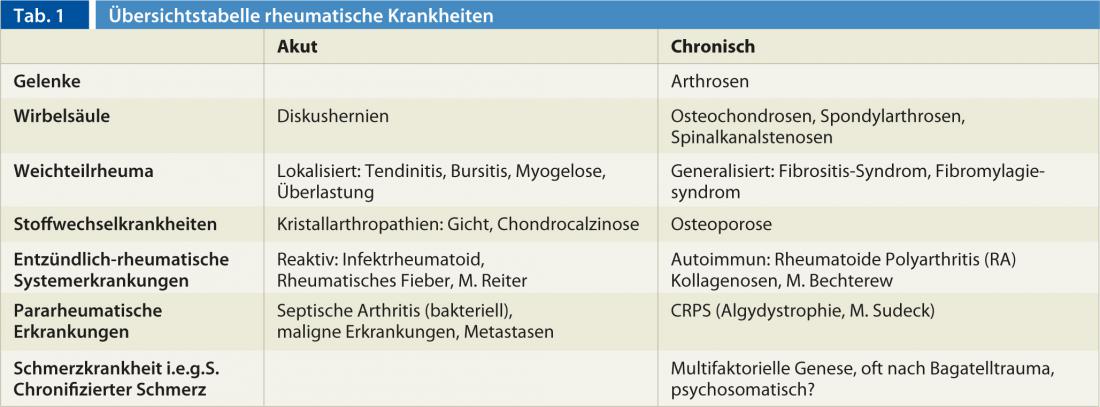

Rheumatic diseases are usually associated with inflammation and pain of the musculoskeletal system. A distinction is made between acute and chronic for both rheumatic systemic diseases and pain. While acute pain has a role in maintaining health and avoiding damage to the body and is usually nociceptive in nature, chronic pain loses its meaningful significance and can develop into a chronic pain disease in the true sense. We speak of chronic pain when it lasts for more than three to six months. This is usually a mixed picture of nociceptive and neuropathic pain. We also distinguish between acute and chronic rheumatic diseases, which must be classified and treated differently. In rheumatic diseases, inflammatory changes and deformities of the joints and spine play a major role in the development of pain (Table 1).

Inflammatory rheumatic systemic diseases

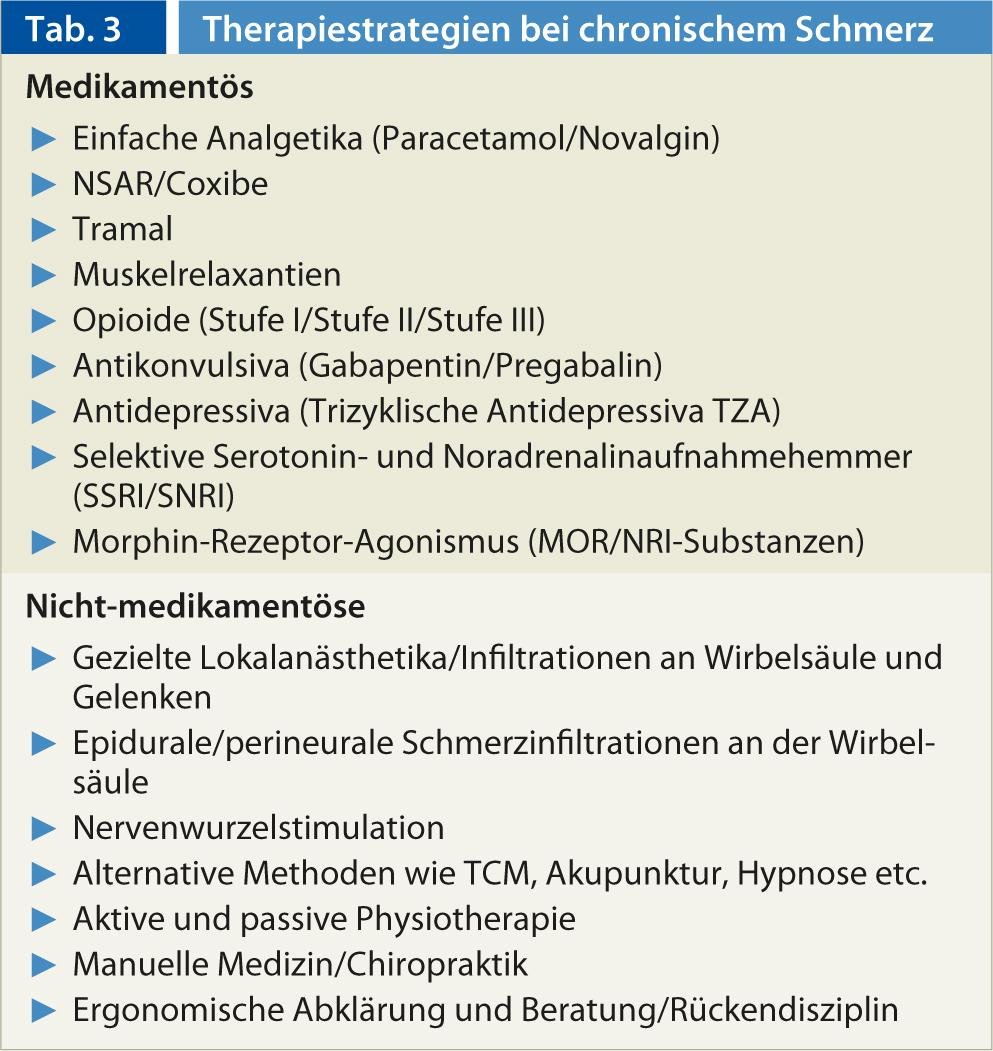

Classic examples of rheumatic systemic diseases are rheumatoid polyarthritis (RA), formerly also referred to as primary chronic polyarthritis (pcP), as well as ankylosing spondylitis/sero-negative spondyloarthropathy and the collagenoses, which can lead to corresponding chronic pain syndromes of the musculoskeletal system due to their protracted chronic course. In these diseases, adequate treatment of the underlying disease is important. For at least ten years, the new biologicals have been available to us for this purpose, along with the tried and tested basic therapeutics (disease modifying drugs/DMARDs), as well as antirheumatic drugs, analgesics and sensibly used corticosteroids.

Pain syndromes in rheumatology

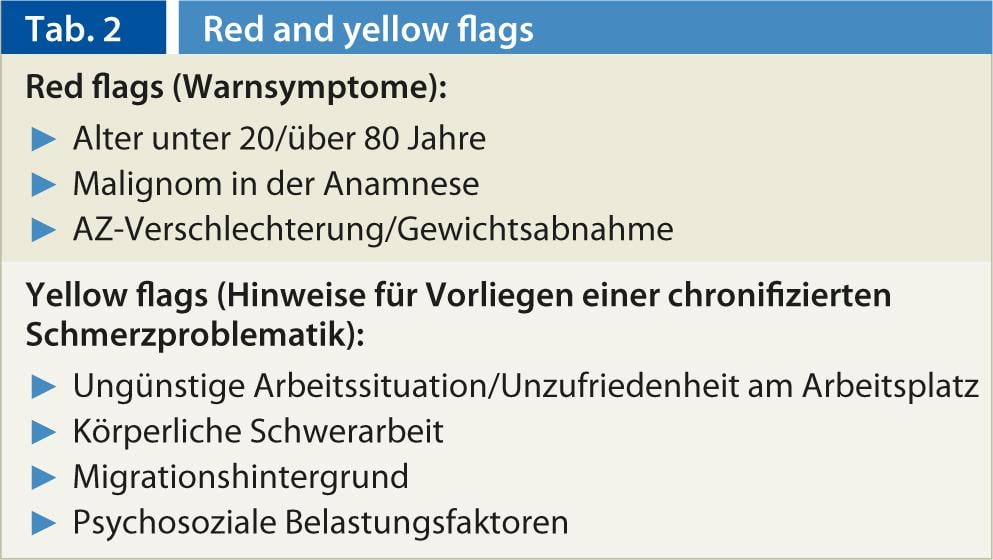

In addition to rheumatic systemic diseases, chronic back pain (so-called “low back pain”) and soft tissue rheumatic pain such as fibromyalgia syndrome (generalized pain syndrome) are playing an increasingly important role in rheumatological practice. These pain syndromes usually develop from an initial acute pain symptom and then, instead of resolving in a reasonable time frame, begin to progress to generalized pain syndrome/chronic pain disorder (ICD 10 somatoform pain disorder) within months. These disorders are diagnosed after somatic disease has been ruled out, and definite diagnostic criteria or findings are difficult to discern. It is important to observe the red flags and the yellow flags (Tab. 2).

Chronic back pain (low back pain)

Chronic back pain is widespread and steadily increasing. Their importance in terms of economic impact, health and treatment costs, pension payments and disability is considerable in industrialized nations and continues to grow. Typical of chronic back pain is the absence of corresponding pathological changes that could really explain the persistence of pain. Further confounding is that the findings are not directly correlated with the reported complaints. Other factors such as psychosocial/sociodemographic factors, work-related factors, and migration background play a significant role here. However, a chronic back pain (low back pain) in the true sense may only be diagnosed after an organic cause has been ruled out (red flags!). These are: Chondrosis/osteochondrosis, disc protrusion/disc herniation, spondyloarthrosis, spinal stenosis, synovial cysts, insertion tendinosis/periostitis/bursitis, osteoporosis/osteoporotic compression fractures, infection, tumor/metastases, fractures.

Generalized soft tissue rheumatic pain syndrome/fibromyalgia

This clinical picture usually arises from an initial acute pain symptomatology, but can also occur primarily as a generalized pain syndrome. Multifactorial causes play a role in its development. Typical symptoms are pain in the area of muscle/tendon insertions all over the body, the so-called tender points, persisting for at least three to six months. For the diagnosis of a fibromyalgia syndrome, tender points are required on at least eleven of 18 points, the so-called fibromyalgia pressure points, which are not to be confused with the irritation zones or myofascial trigger points known from manual medicine. Usually there are additional vegetative stigmata such as functional cardiovascular problems, respiratory problems, headaches, sleep disorders, colon irritabile and depressive disorders.

Fibromyalgia syndrome is still largely unexplained causally, the diagnosis is made from the totality of symptoms and clinical findings after ruling out an organic cause. It is a hypersensitivity of soft tissues of unclear etiology with disturbance of pain processing, and connections with neuroplastic processes, neuro-immunological changes in the central nervous system, disturbances of endorphin production, serotonin-tryptophan concentration, etc. are found.

Therapeutically, fibromyalgia is still a crux, must be approached multidisciplinary, also taking into account the additional psychological factors. Modern drugs such as SSRIs, NSRIs, and NOR/MOR substances (Tab. 3) are important forward-looking therapeutic options and generally work better than NSAIDs and analgesics for these chronic pain disorders. Again, it is important to avoid the threat of deconditioning, appropriate physiotherapy and adequate exercise, and improvement of sleep quality.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- For both rheumatic diseases and pain, we distinguish between acute and chronic.

- Chronic pain usually develops from acute pain. This can often happen very quickly and must be considered during acute pain management.

- Chronification means expansion of symptomatology on all levels: Pain character, pain locations, soma, psyche, vegetative, social life, occupation, family.

Literature list at the publisher

Gerda Hajnos-Baumgartner, M.D.