Drug therapy for diabetes has become increasingly complex over the years. The SGED’s practical therapy guide is intended to shed light on the subject. What is the current therapy in Switzerland?

Most people with diabetes mellitus are over 65 years old. Even in old age, diabetes still plays an important role in life expectancy. It is estimated that a 65-year-old woman in this country still has an average of 22 more years to live, and a Swiss retiree 19 years. In Switzerland, more than half a million of the population lives with diabetes – with up to 40% of those affected in Europe and worldwide still unaware of their diagnosis.

The secondary complications of diabetes in the micro- and macrovascular area must be prevented. 75% of all individuals with type 2 diabetes die from a cardiovascular cause, diabetes is the most common single risk factor of renal failure and dialysis. The frequency of myocardial infarctions in the diabetic population has decreased more than in the general population over the last years (by almost 70% compared to about 30%), but at a much higher level – still about seven times more myocardial infarctions occurred. The association between higher HbA1c and higher cardiovascular risk is clearly established, not only for fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarctions but also for apoplexy, amputation/death due to PAVK, and heart failure (UKPDS long-term data).

The recent studies on the drugs empagliflozin (EMPA-REG OUTCOME). [1,2], liraglutide (LEADER) [3], semaglutide (SUSTAIN-6) [4], and canagliflozin (CANVAS) [5] were positive in their cardiovascular endpoints-that is, they primarily led to a reduction in macrovascular events (death of cardiovascular cause, nonfatal myocardial infarction/stroke); in part, significant results were also found in microvascular endpoints and all-cause mortality.

Procedure in practice

But how to find one’s way through the “kiosk” of diabetes medications, which active ingredients are suitable for the individual patient? Prof. Dr. med. Roger Lehmann from the USZ prepared the SGED recommendations of 2016 for the audience of the Update Refresher once again in a practical way. Basically:

- First step: individual HbA1c target 6.0-8.0% (usually <7%)

- Second step: best individual therapy – set priorities (top priority: avoid cardiovascular complications and hypoglycemia).

- Third step: think in terms of drug classes, choosing the substance with the best evidence.

The goal of the new recommendations was to provide an accessible regimen based on the patient’s key clinical characteristics – elicited using four guiding questions. The SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP1 receptor agonists should be given more weight in this as the “current best diabetes medications.” However, infrequently used drugs with <5% market share such as alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, pioglitazone, and repaglinide were not included.

The four clinical questions that lead to the best therapeutic option according to the Swiss recommendations are:

- Is there an insulin deficiency?

- Renal function: eGFR <30/45/60 ml/min?

- Cardiovascular disease present?

- Prevention/presence of heart failure?

Clinical characteristics

Insulin deficiency (approx. 25% of all patients): This is manifested by symptomatic hyperglycemia, which is clinically noticeable as polydipsia, polyuria, weight loss and volume depletion – in the worst case, metabolic decompensation is imminent. Here, basal insulin is initially recommended – preferably Tresiba® (DEVOTE study) [6]. Thereafter, intensification to a single bolus plus basal insulin, a mixed insulin (Ryzodeg® = Tresiba® and NovoRapid®) or Xultophy® (Tresiba® and GLP1-RA) is possible. Later, finally, a basic bolus regimen.

renal function (eGFR<60 ml/min, 22.4% of all patients): If the eGFR is below 30 ml/min, which applies to 2.4% of all patients, DPP4 inhibitors or GLP1-RA are recommended first – if the HbA1c target is not reached with these, eventually also basal insulin. Linagliptin, unlike the other agents, does not require dose adjustment at the aforementioned GFR.

If eGFR is above 30 ml/min but below 45 ml/min, which applies to 6.1% of all patients, start metformin (half dose) and combine early with SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP1-RA (these show good evidence of nephroprotection). After that, DPP4 inhibitors or basal insulin are again added.

If eGFR is above 45 ml/min but below 60 ml/min, which applies to 13.9% of all patients, also start metformin and combine early with SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP1-RA (nephroprotection). DPP4 inhibitors, glicazide, or basal insulin are then added.

Cardiovascular disease (approx. 20-25% of all patients/approx. 50% asymptomatic): If cardiovascular disease is present, metformin is preferably combined early with an SGLT2 inhibitor (best evidence Jardiance®), and with a GLP1-RA (best evidence Victoza®) if BMI is greater than 28. This is analogous to the therapy recommendation for a GFR >45-60 ml/min. In the former combination, the therapy is oral and the cost is in the medium range, while in the latter it is high and an injection becomes necessary. Both drug classes have a lowering effect on body weight (GLP1-RA even more pronounced).

If there is no cardiovascular disease, the procedure is basically the same, although metformin combined with a DPP4 inhibitor may be considered in addition to the options mentioned. Escalation is with gliclazide or basal insulin.

Heart failure (approx. 10% of all patients symptomatic/approx. 25% asymptomatic): Here, primarily metformin combined with an SGLT2 inhibitor is recommended. DPP4 inhibitors (best evidence: sitagliptin) and finally basal insulin can be added.

“Best in class”

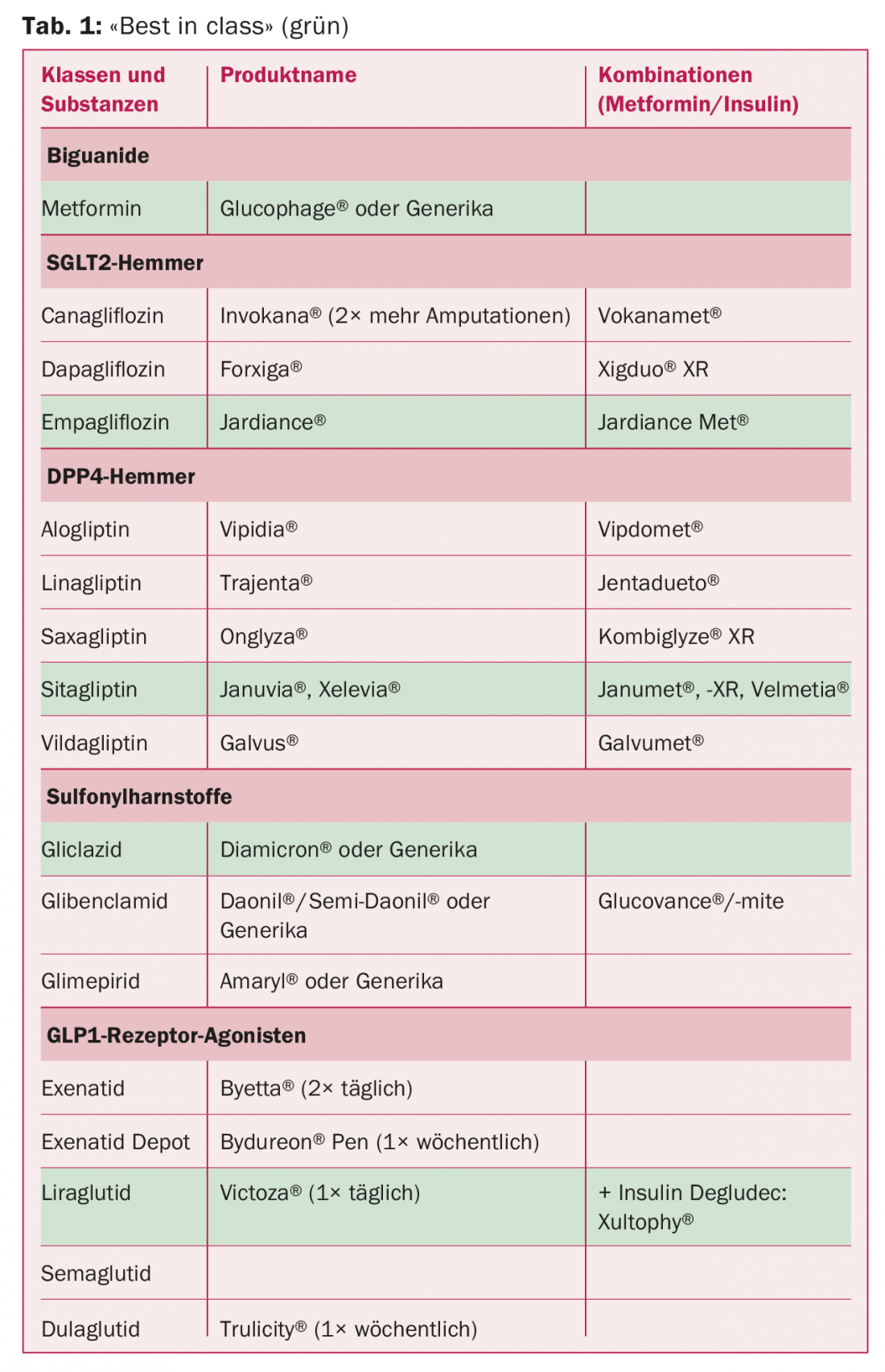

Once the drug class has been selected using the four clinical questions, preference should be given to the substance with the best evidence. According to the SGED, these are the drugs in the class with the currently better data regarding cardiovascular and microvascular endpoints. An overview is provided in Table 1 . Among long-acting insulin analogues, the SGED recommends Tresiba® in particular, followed by Lantus® and Toujeo SoloStar®.

Source: Diabetes Update Refresher, December 7-9, 2017, Zurich.

Literature:

- Zinman B, et al: Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015 Nov 26; 373(22): 2117-2128.

- Wanner C, et al: Empagliflozin and Progression of Kidney Disease in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016 Jul 28; 375(4): 323-334.

- Marso SP, et al: Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016 Jul 28; 375(4): 311-322.

- Marso SP, et al: Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes N Engl J Med 2016 Nov 10; 375(19): 1834-1844.

- Neal B, et al: Canagliflozin and Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017 Aug 17; 377(7): 644-657.

- Marso SP, et al: Efficacy and safety of degludec versus glargine in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017 Aug 24; 377(8): 723-732.

CARDIOVASC 2018; 17(1): 34-36