The term atopic dermatitis was introduced in 1933 to designate certain chronic eczemas occurring mainly in children, in order to emphasize their connection with allergic diseases, such as asthma and hay fever. This naming has since been adopted throughout the world, at least by specialists. In fact, the patients and also the general usage tend to use the simple term of neurodermatitis or even simpler eczema, the words eczema and dermatitis being, by the way, synonymous. In France, the term constitutional eczema was used for a long time, although it must be said that even this expression is not immediately comprehensible. Finally, it was found that this dermatitis or eczema does not always meet the criteria of an atopic disease, which are essentially a positive result in the intradermal test and an increase in circulating IgE. For this reason, people began to speak of “atopiform dermatitis” or “intrinsic atopic dermatitis,” technical terms which, however, remained puzzling to non-specialists. Perhaps it would be better to speak of infantile eczema. Everyone would understand that. But it is difficult to change habits: Scientific articles and official texts talk about atopic dermatitis, and we’ll do it for you here – at least for now.

Atopy is the familial genetic predisposition to develop immediate-type immunological overreactions.

This responsiveness is characteristic with respect to antigenic stimuli as well as humoral and cellular expression. The stimuli, the antigens, which in the present context are preferably called allergens or atopens, are not non-physiological substances such as drugs or toxins. Rather, they are proteins that are present in our immediate everyday environment. Examples include dust mites, which no one can escape, hair from pets, pollen from the plants that surround us, and milk and eggs, which are some of our most everyday foods.

The way in which the allergens in our environment come into contact with our immune system is just as common: through the air we breathe, through the food we eat, and through the skin if it is unusually permeable.

The immunoglobulins involved

Atopic reactivity, in turn, is special: it brings into play a rare class of immunoglobulins, the IgE. The IgE are produced by B lymphocytes. This occurs under the influence of a class of T-lymphocytes specialized in allergy-type immune responses, known as TH2. Effector molecules for this process are interleukin 4, 5 and 13. Certain genetic polymorphisms affecting these cytokines as well as their receptors, including that of interleukin 4, make affected individuals particularly susceptible to atopic dermatitis. IgE circulate in very small amounts in the blood.

Rather, they are found in the tissues. They bind to specific receptors located on the surface of certain cells, such as eosinophils or basophils. It is this binding that sets the allergic reaction in motion. In the course of atopic dermatitis, IgE receptors are found on the epidermal Langerhans cells, which present the allergens to the lymphatic system.

The significance of an increase in IgE

When IgE (immunoglobulins E) were discovered at the end of the 1960s, it was believed that we now had a blood test to diagnose allergies. In the presence of eczema of unknown cause, for example, a normal

blood value for IgE can exclude atopic eczema, while an elevated value can confirm it. Unfortunately, these expectations had to be scaled back.

The false positive or false negative results are far too numerous for this test to be found reliable. For the same reason, skin tests for the diagnosis of immediate-type allergic reactions do not represent progress in the diagnosis of eczema.

Allergen restriction: a debated but questionable measure

If reliable immunological tests are not available for diagnosis, can the eczema at least be alleviated by eliminating certain allergens? This idea sounds promising. If a patient develops urticaria after treatment with penicillin, it should be sufficient to stop giving them penicillin to prevent it from occurring. Consequently, by banning cat dander from the environment of an atopic child who has tested positive for it, one should also be able to make his eczema disappear or at least alleviate it. However, the matter is much more complicated. In the case of atopic dermatitis, positive tests prove only an atopic constitution and not that the eczema is an allergic reaction to cat dander. Thus, after numerous large-scale clinical studies, one has then begun in recent years to dispense entirely with measures for allergen avoidance or, even more generally, with measures to modify the environment. The list of hopes dashed as a result is long: with regard to nutrition, changes in milk do not bring anything, unless these are motivated by digestive problems; probiotics have ultimately proved ineffective, despite initial promising trials. Very few hospitals perform double-blind provocation tests (after prior elimination diet), which are the only diagnostic tool that can prove the causal relationship between a food and the occurrence of eczema. Studies of breastfeeding as well as early food diversification have shown conflicting results.

Even though breastfeeding is usually recommended, it cannot be assured that the child will be saved from eczema later. With regard to respiratory allergens, the numerous studies conducted in recent years do not allow the conclusion that measures of abstinence would have a positive effect on atopic dermatitis. This mainly concerns eczema caused by dust or pets.

The atopic dermatitis a disease of the epidermis

It has long been known that eczema is not the only abnormality in atopic dermatitis. Very often, there is also a skin dryness known as atopic xerosis, as well as other signs that are considered secondary criteria of atopic dermatitis. The real significance of this atopic skin dryness was clarified in 2006, when a team of Scottish geneticists was able to show that mutations in the gene coding for the protein filaggrin are a predisposing factor for the development of atopic dermatitis.

Filaggrin is a protein whose name is due to its function, which is the mutual aggregation of keratin filaments in the keratinocytes of the stratum granulosum. Subsequently, filaggrin is broken down into small hydrophilic molecules, which are involved in the hydration of the stratum corneum. In this way, filaggrin is important both for cornification, the final step in the differentiation process of the epidermis, and for hydration of the skin. A complete deficiency of filaggrin characterizes ichthyosis vulgaris, the most common of the heritable ichthyoses. In addition, the relationship between the two diseases of ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic dermatitis was brought to light by studying families of ichthyosis patients with concurrent atopic dermatitis.

From epidermal abnormalities … to immunological abnormalities

This discovery has stimulated numerous papers(1) that have confirmed the frequent occurrence of filaggrin mutations in patients with atopic dermatitis. It has also been shown that such a filaggrin deficit is characteristic of severe cases of atopic dermatitis and especially of cases of atopic dermatitis associated with asthma. The mechanism of the relationship between filaggrin deficit and asthma was elucidated by animal experiments with mice:

Due to the epidermal malformations allergens from the ambient air can penetrate the stratum corneum and stimulate dendritic cells of the epidermis and dermis, triggering IgE sensitization. The atopic epidermis is not only deficient in filaggrin: Other proteins that play a role in the cornification process, like the Loricrin, which is the main component of the cornified envelope of corneocytes, or the Claudine, which ensure the cohesion (tight junctions) of the keratinocytes, are also insufficiently available. Certain proteases work excessively, which simultaneously leads to the formation of scales and inflammation. Thus, it becomes understandable why skin dryness and inflammation of eczema are present at the same time.

Finally, the intercellular lipids of the epidermis have an abnormal composition with a deficiency of omega-6 class fatty acids. In view of the results of work carried out, these epidermal abnormalities acquire a new meaning: in the traditional model explaining atopic dermatitis, immunological inflammation evokes lesions of the epidermis, eczema and skin dryness. In the newer model, the epidermal malformations are considered to be primordial and trigger inflammatory eczema, with or without immunologic involvement.

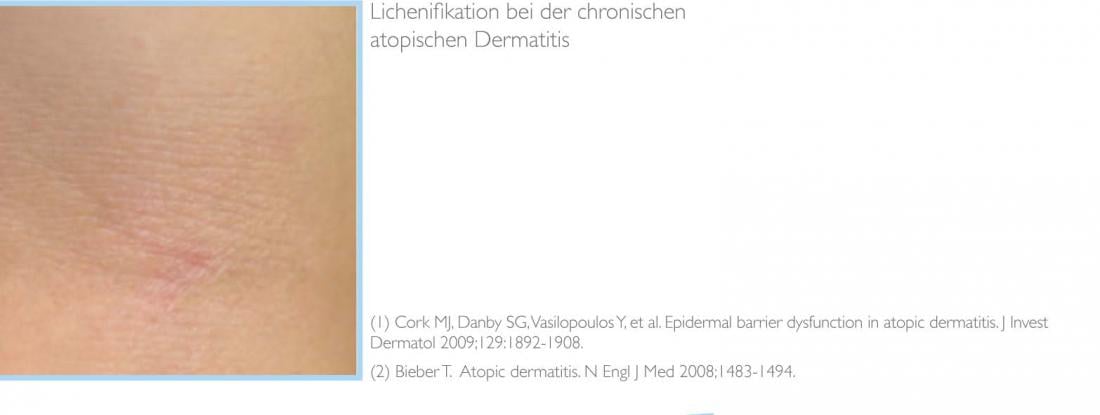

These two different ways of looking at things can certainly be combined. Thus, a comprehensive concept has been proposed in which atopic dermatitis is primarily a disease of the epidermis, but then also represents an immunologic problem-with exogenous allergens and unnaturally numerous staphylococci present on the skin-and finally an autoimmune disease in which inflammation is self-perpetuating, resulting in chronic eczema (2).

A new concept of atopic career

These discoveries shed new light on the concept of atopic careers. This concept was proposed to point out the fact that the different atopic manifestations line up during life: Atopic dermatitis begins in the first months of life; food allergy occurs in the first two years of life; asthma manifests in infancy; and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in young adults. The concept of an atopic career is controversial. On the one hand, it has been proved that the tendency to bronchoconstriction in later asthmatics is present from birth, regardless of the presence or absence of atopic dermatitis. On the other hand, it is not advisable to invoke the risk of asthma in children, few of whom will ultimately actually develop asthma.

Can respiratory sensitization be prevented?

However, the discovery of the role of epidermal malformations opens new perspectives: According to convincing data, the origin of respiratory sensitization lies in the transepidermal penetration of allergens from the air. It can therefore be hoped that respiratory sensitization can be prevented by treating atopic skin dryness with emollients.

A complex treatment

Atopic dermatitis thus results from a complex interplay of genes – immune system genes and epidermal protein genes – and skin-, air-, and diet-specific environmental factors. Unfortunately, genes cannot be influenced and it has been shown that atopic hypersensitivity can be influenced only slightly even by changes in the environment. However, the new evidence provides the rational basis for a treatment strategy whose efficacy is well established. This treatment, which seems simple in theory, is actually complex. Thus, it must be adapted to each patient’s circumstances and, as part of a comprehensive approach, also take into account personal as well as family and psychological factors.

Epidermal anomaly correction

All experts agree that the use of emollients must be the basis of the therapy of every patient with atopic dermatitis. Regular use of an emollient leads to strengthening of the structural elements of the stratum corneum and improves its function. The term barrier function refers to the main task of the epidermis, which is to ensure the integrity of the organism and, in particular, to effectively prevent the penetration of allergens and microorganisms from the environment.

Barrier function is quantified in the laboratory by measuring transepidermal water loss (TEWL) or by directly measuring the moisture content of the skin (corneometry). However, these tests are not performed in the clinic. Rather, for simplicity, it is assumed that smooth and supple-looking skin has a normal barrier function. Such a well hydrated epidermis also counteracts the penetration of staphylococci

which are exceptionally often present on the atopic epidermis. This colonization with staphylococci proves the deficient mechanisms of innate immunity, which normally form the first line of defense of the epidermis against infections. The role of staphylococci in atopic dermatitis is poorly understood. Outbreaks of infection are relatively rare. Staphylococci are thought to have an immunological function in the sense of a “superantigen” and are thus involved in triggering inflammatory episodes. The potential benefits of using antiseptics and antibiotics are still controversial.

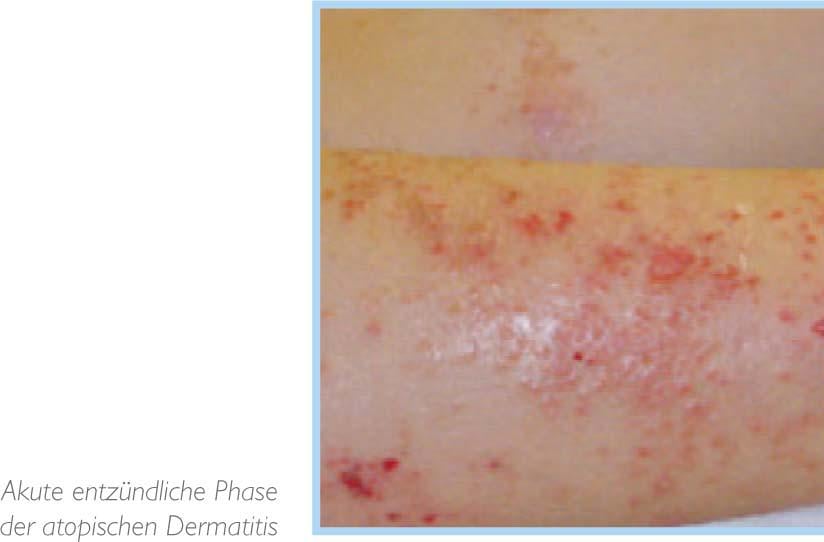

The treatment of inflammation and its consequences

Treatment of atopic xerosis by daily application of emollients is essential. It reduces the frequency and duration of atopic dermatitis episodes, but cannot suppress them completely. In case of acute and itchy eczema, local therapy with corticosteroids is inevitable and beneficial. Local treatment with corticosteroids is certainly the most effective of all dermatological therapies, but also the most unknown. And this despite the fact that their implementation is simple, their effectiveness is remarkable and side effects can be practically excluded, provided that the application is done correctly. From the age of two years, treatment with topical tacrolimus may also be given. Oral corticosteroids play practically no role in the therapy of atopic dermatitis. They quickly lead to a dependency from which it is difficult to find your way out. In contrast, to repeat, local corticosteroids are effective and safe.

The benefits of H1 antihistamines have been studied in numerous papers. Clinical experience recognizes its potential for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. However, they do not affect atopic inflammation, in the development of which histamine does not play a major role. It is thought that the antihistamines may be beneficial primarily because of their antipruritic effects.

Listen and inform

Certainly, atopic dermatitis is primarily a disease of the epidermis. However, due to its chronicity and the intensity of the itching, it can also entail generalized consequences, sometimes of a more severe nature: First and foremost are sleep disturbances, which are caused by the itching and have a negative effect on the entire daily activities of both the child and his parents. Quality of life assessment scales that measure the general, psychological, and social impact of chronic disease show that this impact is substantial in the case of atopic dermatitis.

Determination of this general measure should be performed in all patients. In the majority of cases, sufficient improvement can be achieved with well-executed standard treatment. This standard treatment requires several consultations as well as attentive listening. However, more needs to be done for certain patients. This is where facilities that provide more intensive care come into play. Spas perform this task efficiently by combining hydrotherapy, intensive dermatological treatment and patient education. Recently, dermatological centers have started offering workshops or creating schools dedicated to the topic of atopic dermatitis. Such facilities make it possible to provide intensive care, information about the disease and training in proper care. For some families, these services are irreplaceable and help them find their way out of seemingly intractable situations.

Summary

This overview of the most important elements in the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis makes it understandable why this disease has such a great importance in research and in dermatological practice. The starting point is a structural deficit of the stratum corneum, the layer located on the surface of the skin, whose outstanding importance has only recently been recognized. After that, everything interferes with each other: Xerosis leads to itching, inflammation, scratching, infections and general sensitization. Itching causes significant functional impairment, depresses mood, burdens daily life and causes personal and family suffering. Can all of these conditions be alleviated by improving epidermal function?