Artificial intelligence can make an initial melanoma diagnosis with convincing accuracy. Only the really suspicious cases would need to see a dermatologist. Apps with photoaging effect also strengthen preventive awareness.

The ratio of benign moles excised on suspicion to malignant melanomas actually diagnosed is the Number Needed to Treat (NNT). It is the number of treatments (excisions) that must be performed to achieve a desired therapeutic event (melanoma removed). It is an indicator of diagnostic accuracy in the clinic and of the efficient use of medical resources. Unnecessary surgery can be avoided with a deep NNT. According to studies [1,2] specialists have an NNT between about 6 and 8. In family practices it can be 17 or (significantly) more, family physicians with an interest in this area come to NNT values around 9.

The commercial MoleMap program (https://molemap.net.au), under which Australian, New Zealand, and American physicians with expertise in screening for melanoma offer low-threshold “check-up packages,” boasts an NNT of 4. Patients decide for themselves whether and to what extent to participate in the screening program. This has resulted in a database of more than six million photographed lesions, either at the macro level (magnified clinical image) or at the micro level (via dermatoscope, polarized/non-polarized).

Artificial intelligence reaches NNT of 7

IBM researchers from Australia used some of this data, 40,173 images from 8882 patients, along with the diagnostic information to teach an artificial neural network to diagnose melanoma. With this, the artificial intelligence learned to classify lesions into “melanoma” and “non-melanoma” (basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and twelve benign diseases) based on micro and macro images. Data from 80% of patients – randomly selected – served as the basis for the learning algorithm, and the remaining 20% as a test of the model’s accuracy.

In fact, the artificial intelligence achieved an NNT of 7 when the number of lesions recommended for treatment by the algorithm was compared to the melanoma diagnoses made by MoleMap dermatologists. Translated, this means: Artificial intelligence moved within the values of specialists.

Agreement with dermatologist diagnosis was 96.58% (micro), 96.34% (macro), and 96.75% (micro and macro combined). The area under the curve (AUC) was above 0.9. Accordingly, the test discriminated cleanly and clinically relevant.

Because of its good agreement with expert diagnosis, the algorithm could be used in the future to ensure that only truly suspicious lesions reach the dermatologist. The rate of eligible lesions is reduced, and the efficiency of testing is increased. Incidentally, similar developments were also reported in Switzerland a few years ago (Skin App from Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts).

Artificial aging via app as an educational tool?

Interesting thoughts on digitization also came from Germany. If (unprotected) UV exposure is the biggest risk factor for skin cancer, can’t broad public awareness be raised via digital media? For example, could the widely used face modification apps that are primarily aimed at entertainment be used for this purpose? The procedure is familiar: A “selfie” of one’s own face is required, which with one click suddenly appears aged or rejuvenated by several years, mixed with the likeness of another (face swap), or changed in gender.

Researchers from Germany conceptualized an app in this style that “conjures” photoaging and skin cancer on the user’s face. Specifically, future appearance can be observed in 3D and over a lifespan of five to 30 years (depending on whether or not you protected yourself from the sun every day). This makes the effects of premature UV-induced skin aging visible and tangible. Squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma are added to the appearance with a button. The result is again adapted to the use of sunscreen. In addition, there is information on probabilities and risks of developing skin cancer. In terms of a learning gain, the app shows you how to best protect yourself from the sun and how to recognize suspicious skin lesions.

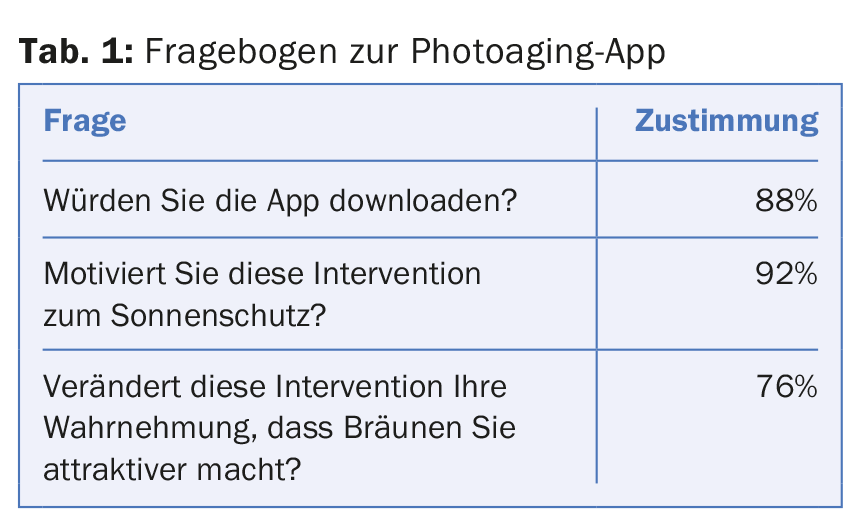

To test how the app is received by the target group, 25 students of both sexes were surveyed at the University Hospital in Essen using anonymous questionnaires. Using a five-point Likert scale, various views on the app were recorded from the average 22-year-old (Tab. 1) . The feedback was predominantly positive.

In May 2017, the app was released, along with a corresponding poster for integration into school lessons. The researchers hope to gain awareness, especially among the young at-risk group, by focusing on aesthetics/cosmetics. Of course, this gives the project a certain attack surface. Is a corresponding reduction in content and entertaining presentation of the problem really the way to go in skin cancer prevention? The answers will vary – but it is clear that the younger generation should be sensitized to the topic and that the usual arguments for sun protection are not effective in all populations. Abstract risk calculations can miss their target; a prevention campaign and preparation tailored to the target group can be profitable in this context.

Source:9th World Congress of Melanoma, October 18-21, 2017, Brisbane.

Literature:

- Sidhu S, et al: The number of benign moles excised for each malignant melanoma: the number needed to treat. Clin Exp Dermatol 2012 Jan; 37(1): 6-9.

- Rosendahl C, et al: The impact of subspecialization and dermatoscopy use on accuracy of melanoma diagnosis among primary care physicians in Australia. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012 Nov; 67(5): 846-852.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2017; 27(6): 42-43