Psycho-oncological support needs do not necessarily think of themselves in terms of patient distress. A sensitive and step-by-step approach is therefore indicated in order to uncover possible ambivalences.

A cancer diagnosis is devastating for both the patient and those around them, and leads to many changes and challenges. It is therefore not surprising that people diagnosed with cancer often suffer from high psychological and social stress, which can have a negative impact on both treatment and quality of life. International professional societies therefore recommend that the psychosocial burden of cancer patients be routinely assessed with short questionnaires, so-called screening questionnaires. The goal is to identify patients with high psychosocial distress. This has led to the fact that in hospitals where these questionnaires are used, stressed patients can be identified more quickly and psycho-oncological support can be offered to them at an early stage. The introduction of stress screening in treatment has become a certification criterion for cancer centers.

Need for support does not necessarily follow the load

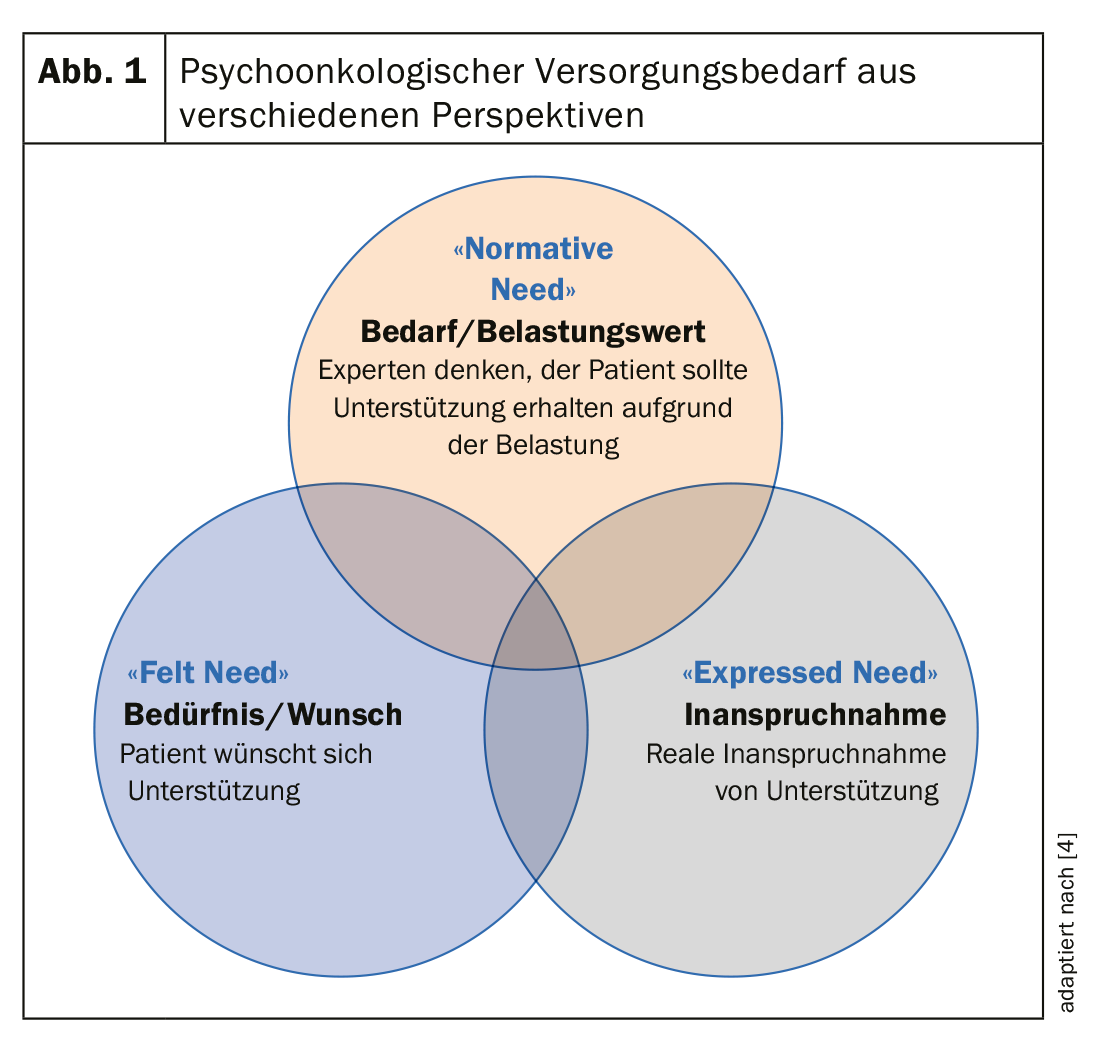

However, research has shown that only a small proportion of ill patients take advantage of the psycho-oncological support offered, surprisingly largely independent of their self-reported distress. To understand this result, it is important to distinguish between different types of care needs. Salmon [1] recently pointed out to differentiate psycho-oncology care needs. First, there is the need for support, which can be defined by the fact that those with elevated stress levels are at increased risk of developing a mental disorder in the course of their illness. The fact that these patients have a need for care is based on the expert perspective, but does not necessarily coincide with the affected person’s perspective. The need from the patient’s perspective is reflected on the one hand in the desire for psychosocial support and on the other hand in whether psycho-oncological support is actually used in the course of treatment. So we can distinguish three types of supply needs:

- Supply requirements due to an increased load,

- the expressed desire for support without necessarily also making use of support,

- The effective use of psycho-oncology support.

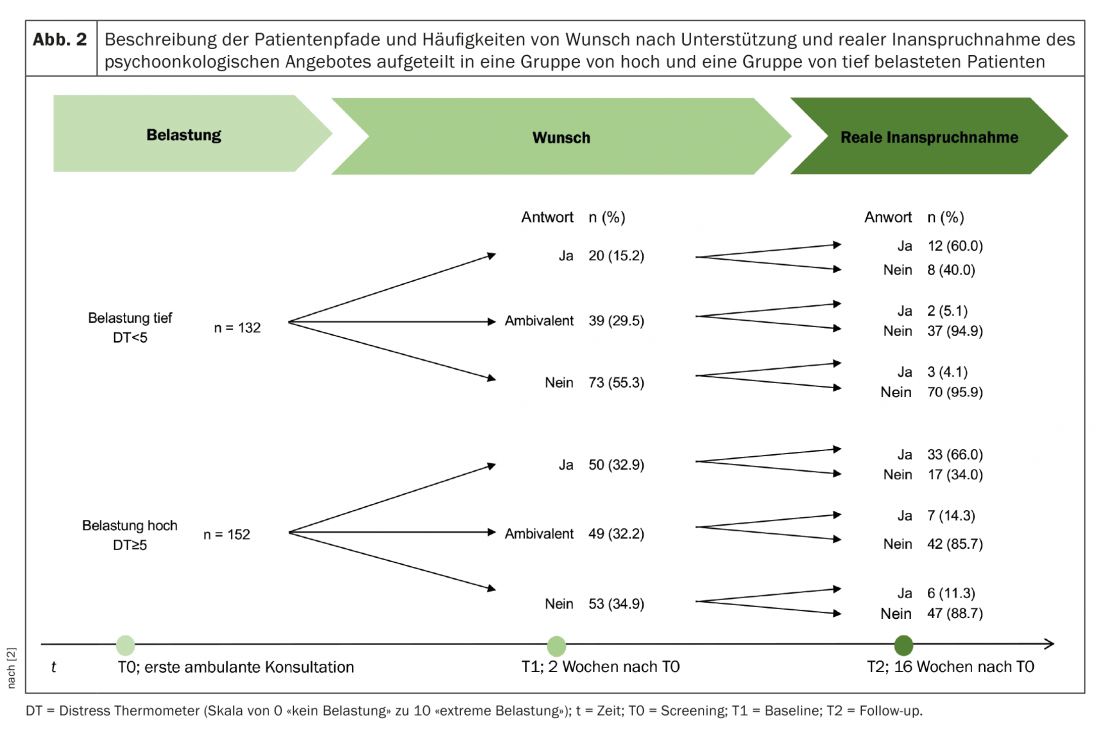

In English, the terms “normative need”, “felt need” and “expressed need” are used for differentiation [1]. (Fig. 1). These research results were the starting point for our own research project: Within the framework of a study supported by the Swiss Cancer League, our Basel study group dealt intensively with the topic of stress screening and psycho-oncological care needs [2]. Data from 333 study participants who had a first outpatient appointment in medical oncology at the University Hospital and subsequently sought oncology treatment were analyzed. At the time of the first appointment, with usually detailed discussion of the upcoming oncologic treatment, slightly less than half of the patients showed elevated stress levels (stress thermometer 5 or greater). From an expert perspective, they therefore had a need for psycho-oncological support. When those affected were asked themselves, one third of these patients had a clear desire for support. Another third had no desire for support, and the third third was ambivalent about it. That is, over one-third of individuals with high stress scores had no desire for support, and nearly half of patients with low stress scores wanted or may have wanted to seek support. (Fig. 2) [3].

Recognize and understand ambivalences

Although well known from clinical practice, the ambivalence of affected persons regarding psycho-oncological support has not been scientifically investigated so far. The large group of ambivalent patients is particularly interesting because, on average, they reported a high level of distress but had barely taken up the offer after four months. The ambivalent patient population is therefore one that has not been described before, but one that we would like to better understand and reach.

In a further analysis, this time qualitative, we investigated the motives of those affected for or against making use of the psycho-oncology service [3]. In interviews, patients were asked to describe their thoughts for this. We were able to record a total of 734 arguments for or against psycho-oncological support and define 32 superordinate categories from these. These 32 categories could be grouped into four central themes, regardless of whether respondents expressed support for or opposition to utilization. In ambivalent patients, arguments were found both for and against psycho-oncological support, because this group of patients found motivations for both paths. A first important issue was the general attitude towards psychological support. Further central topics were the experienced stress, the handling of the disease resp. coping with the disease, and finally the formal and informal support experienced.

Overall, a different pattern of justifications was found between patients with ambivalence and those with a clear yes for or no against psycho-oncology support. For ambivalent patients, the current situation with all the uncertainties, fears, but also the available resources seemed particularly relevant for their weighing. In addition, these patients describe themselves as basically open to psycho-oncological support, which is an important distinction from the patients with a clear no. Patients with a clear no or clear yes show significantly more reasons, which are based on a positive or negative attitude or a clear idea of how they want to deal with the disease situation.

The conversation remains central

In summary, routine assessment of distress is a significant advance in psycho-oncology care to better identify distressed patients. The patient’s wishes may or may not correspond to the expert perspective on support needs. The reasons for this are complex. Patients who reject support often show more negative attitudes toward psychological support. In addition, there are a considerable number of patients who are less stressed but who gladly accept psycho-oncological support. One group that has received little attention so far is that of patients who are ambivalent. This group can be described as a vulnerable group with increased distress in the mean and low utilization in the course, albeit with an often open attitude towards psycho-oncological support.

In light of our findings, we recommend that a step-by-step approach be taken in the clinical setting to assess burden and desire for support, including ambivalence in particular. Discussion of the stress thermometer should be used to understand the person’s stress in context and to inquire about their desire for support, addressing negative attitudes toward psycho-oncological support, if any. If affected individuals are ambivalent, special attention should be paid to asking them again about their distress as they progress and to discussing when psycho-oncological support is appropriate. In general, it is important to show those affected that a disease has not only medical but also psychological and social consequences, for which experts are available to provide advice. Whether for a one-time psycho-oncological consultation or a longer, resp. psychotherapeutic support. Another finding supports the importance of conversation: our models showed that an oncologist’s recommendation to accept psycho-oncology support was one of the most important predictors of utilization [4]. Therefore, in order to further optimize psycho-oncology care and facilitate access for underserved groups of patients, we believe that talking about distress as well as support needs should not be replaced by the use of screening questionnaires such as the distress thermometer, but should be complemented by it.

Literature:

- Salmon P, et al: Screening for psychological distress in cancer: renewing the research agenda. Psychooncology 2015; 24(3): 262-268.

- Zwahlen D, et al: Understanding why cancer patients accept or turn down psycho-oncological support: a prospective observational study including patients’ and clinicians’ perspectives on communication about distress. BMC Cancer 2017; 17(1): 385.

- Tondorf T, et al: Focusing on cancer patients’ intentions to use psycho-oncological support: a longitudinal, mixed-methods study. Psycho-Oncology 2018; 1-8.

- Frey Nascimento A, et al: Oncologist recommendation matters!-Predictors of psycho-oncological service uptake in oncology outpatients. Psycho-Oncology 2018 Nov 22 [Epub ahead of print].

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2019; 29(5): 24-26