The onset of schizophrenic psychosis is usually gradual and atypical. Their early detection has become the focus of psychosis research. An overview of psychotic symptoms in the prodromal stage and their further expression in the early stage.

The onset of schizophrenic psychosis is usually gradual and atypical. Early detection and early treatment of such disorders have gained importance in recent decades and have become the focus of psychosis research. By establishing specialized screening centers, patients suspected of being at risk for psychosis can be comprehensively assessed and, if necessary, treated or referred appropriately. Early intervention can significantly improve the course [1–5].

Symptomatology

Most psychotic illnesses are preceded by a nonspecific prodromal stage that lasts about five years on average, but can be much shorter or longer. The mostly young affected persons behave “somehow strangely”, are “just not the old one anymore”, show complaints such as loss of interest, social withdrawal or lower resilience in everyday situations and are no longer able to fulfill the previous roles in education/profession, partnership and family. A so-called “kink in the lifeline” occurs.

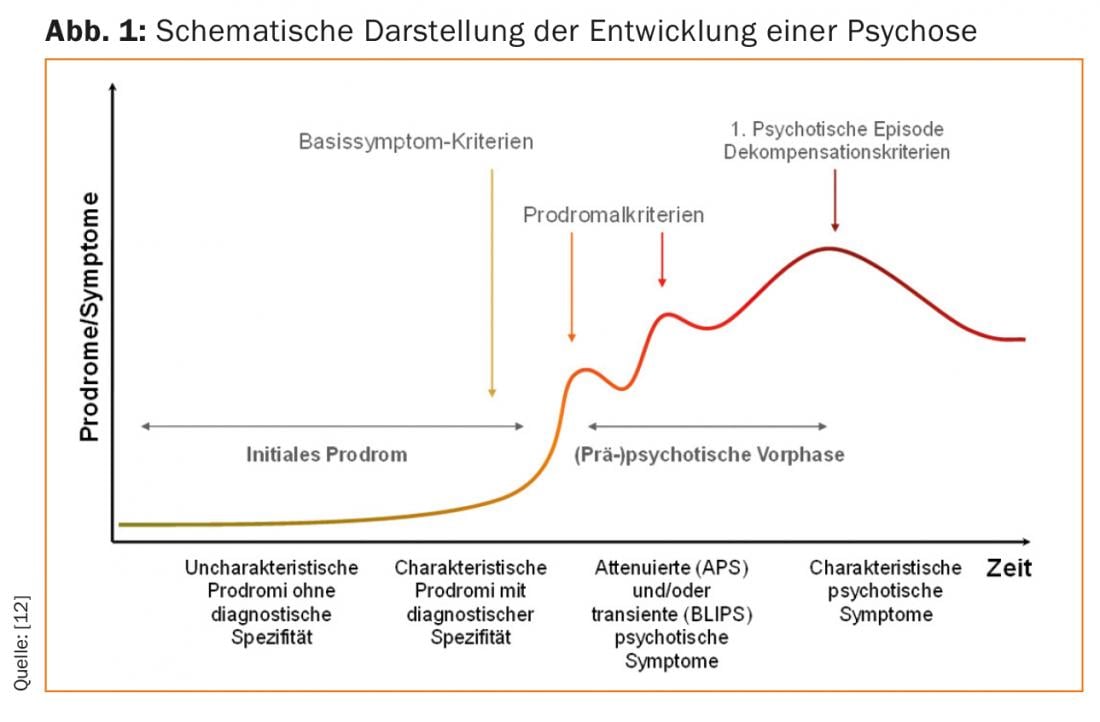

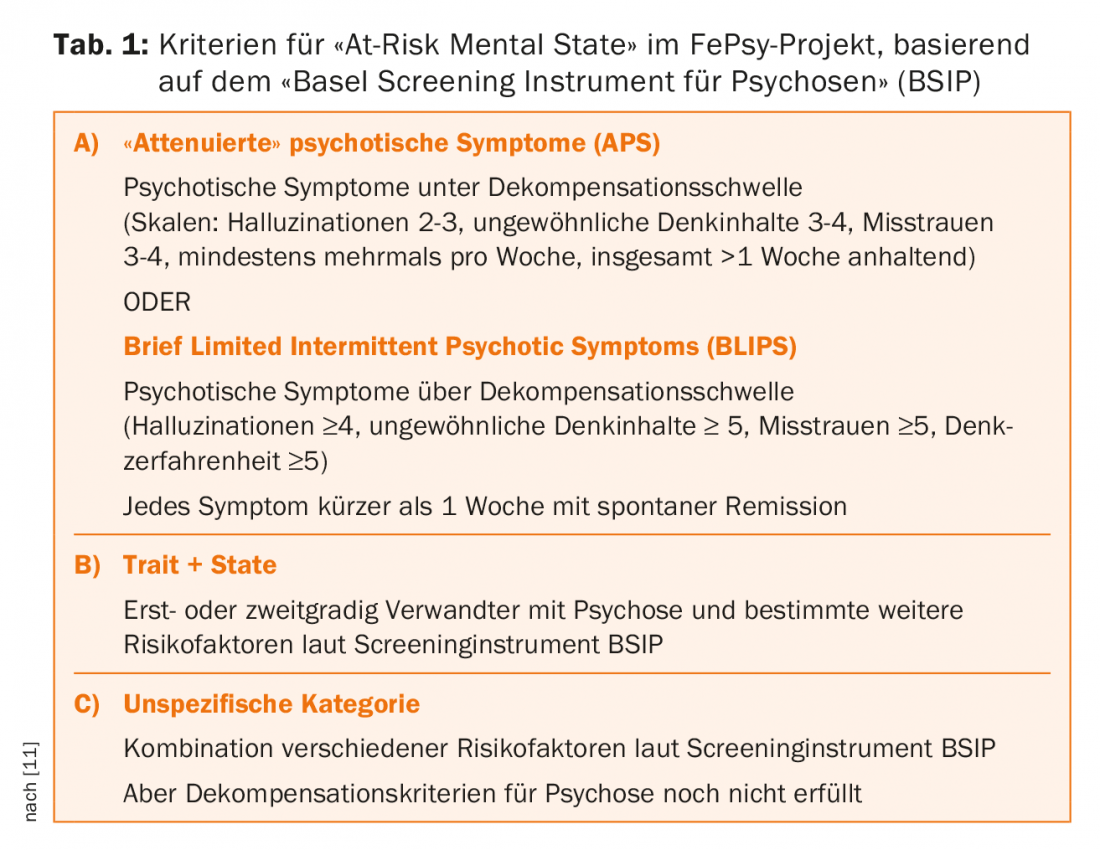

On average, the first specific pre-psychotic symptoms appear one to two years before psychotic decompensation (Fig. 1). A distinction can be made between so-called “attenuated psychotic symptoms” (APS) and “intermittent psychotic symptoms” (BLIPS: brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms). Prepsychotic symptoms are understood to be those that are less severe in quality, intensity, and frequency than psychotic symptoms, i.e., subthreshold forms of delusions, hallucinations, or ego disorders. BLIPS, on the other hand, are transient psychotic symptoms that are as severe as symptoms of psychotic decompensation, but are extremely short-lived (one week at most) and remit spontaneously without any treatment (Table 1).

The goal of early psychosis detection is to identify and treat patients with a prodromal stage as early as possible. Patients who seek help in a screening consultation and present a certain combination of different symptom characteristics in specially developed screening interviews are considered at-risk patients. In English-speaking countries, this risk status is also known as the “at-risk mental state”. These are referred to as “high-risk” or “clinical-high-risk” patients.

Risk factors of transition to psychosis in high-risk patients.

Overall, approximately one-third of all patients with an identified risk status transit within 36 months of initial presentation [6]. That is, the predictive accuracy of these screening interviews is already relatively high. However, in today’s research, great efforts continue to be made to further improve predictive accuracy by attempting to find predictors of particularly high transition risk in these high-risk patients.

It has been shown that clinical characteristics present at baseline are highly predictive of transition. For example, patients with BLIPS have a significantly higher risk of transition than patients with APS (39% vs. 19% at 24 months). In addition, it should be noted that a low global or social functioning level at baseline is an additional predictor of later transition.

Genetic burden: the role of heredity is thought to be very high in schizophrenic psychosis. Nevertheless, studies have shown that individuals with a genetic predisposition to the condition still have a significantly lower risk of short-term transition than patients with APS or BLIPS. Genetic risk is obviously more likely to have a longer-term effect. Other factors influencing a possible transition may include changes in DNA methylation or certain deletion syndromes (for example, 22q11.2) [6].

Psychotropic substances: Amphetamines, hallucinogens or cannabinoids can be triggers of acute psychosis. In some cases, they can also be triggers for persistent schizophrenic psychosis (see also “Beck et al.: Cannabis and incipient psychosis” in this issue) [6].

Sociodemographic variables: Patient gender and parental socioeconomic status have not been shown to be predictive of subsequent transition to psychosis in various studies. In contrast, the study evidence regarding education, parental education, and age is mixed [6].

Childhood trauma: Some older studies reported childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of transition in at-risk patients. However, more recent studies have not been able to replicate this finding [6].

Stigma and discrimination: both experienced discrimination and stigma have been reported as predictive risk factors [6].

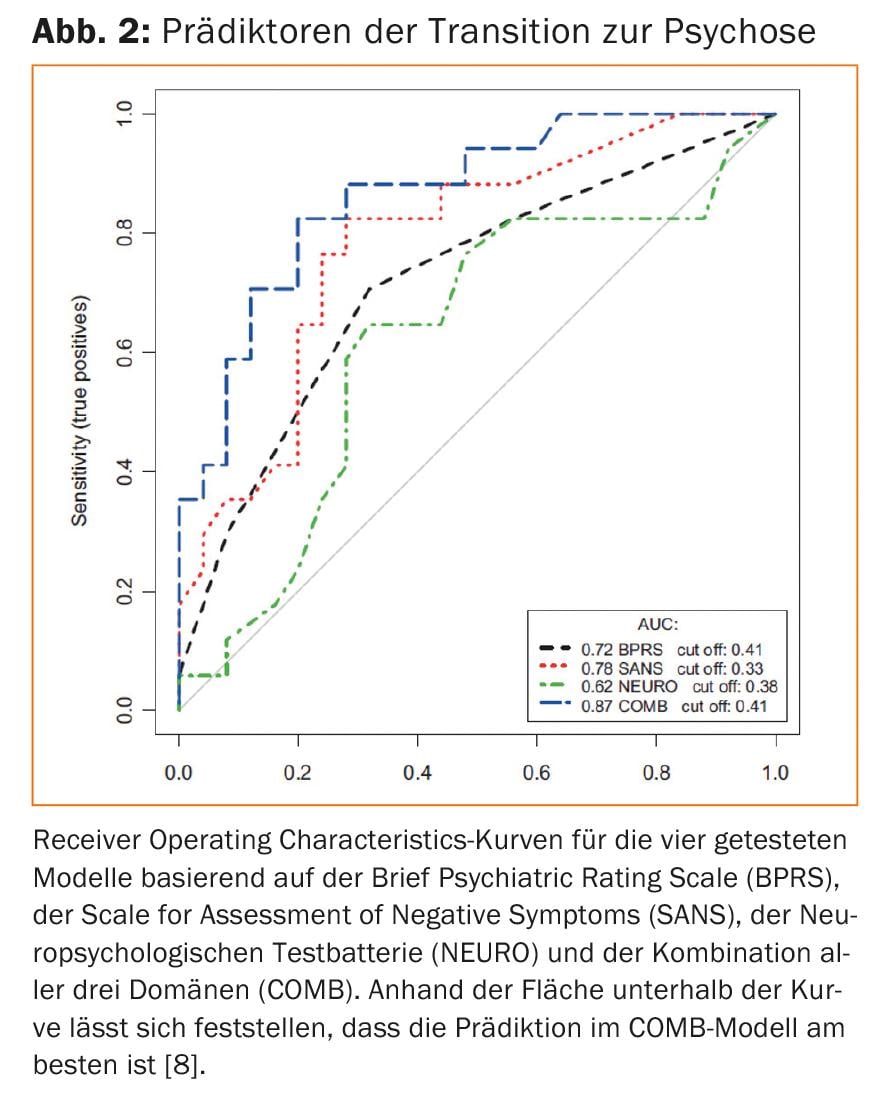

Neurocognition: across all cognitive domains, significantly worse performance was found in patients with later transition compared with non-transitioned patients [7,8].

Neuroimaging: changes in the volumes of diverse brain structures such as the medial temporal lobe, prefrontal and cingulate cortex, integrity of white matter tracts, and altered activation of the prefrontal cortex, medial temporal lobe, or nucleus caudatus have been reported more frequently in patients with late transition than in patients without transition to psychosis [6].

Neurophysiology: various parameters from the clinical and quantitative electroencephalogram (EEG), the mismatch negativity or the event-related potential P300 could make significant contributions to the prediction of psychosis in studies [6].

Blood parameters: Increasingly, blood parameters such as elevated plasma inflammatory markers, oxidative stress, or hypothalamic-pituitary axis dysfunction are being considered for predicting possible transition [6].

Multidomain models: In the context of prediction models, different risk levels can be simultaneously examined and evaluated for their predictivity. This approach allows the risk factors to be ranked in terms of their weight for prediction. For example, studies by our research group have shown that consideration of both positive and negative symptoms and neurocognitive performance improved prediction. A combination of the three factors mentioned above provides the best prediction (Fig. 2) [8].

Newer methods also allow prediction at the individual level. We have performed such calculations using machine learning on neuroimaging data, for example. They are currently being replicated and further refined in large European multicenter studies [6].

Consequences of untreated psychoses

If psychotic illnesses are not recognized and treated at an early stage, serious consequences can occur even in the early stages of the illness. Among other things, there may be delayed or incomplete remission of symptoms, lower compliance, and higher rates of rehospitalization and treatment costs. Furthermore, there may be a reduction in quality of life due to impairment of psychological, social and occupational development. The family environment often becomes highly stressed and patients are at increased risk for depression, suicide, homicide, delinquency, and abuse of alcohol or drugs [1,9].

Early detection

The clarification of the risk status or the initial psychotic illness takes place in clinical examinations and includes standardized interviews, neuropsychological tests, blood tests, EEG and MRI measurements [9,10]. In the first screening consultation in Switzerland in Basel (FePsy), the “Basel Screening Instrument for Psychoses” (BSIP) was specifically developed for the survey of the risk status [11]. The BSIP shows very good interrater reliability and predictive validity and is easy to use for experienced psychiatrists. Table 1 summarizes the risk categories used for the risk status survey.

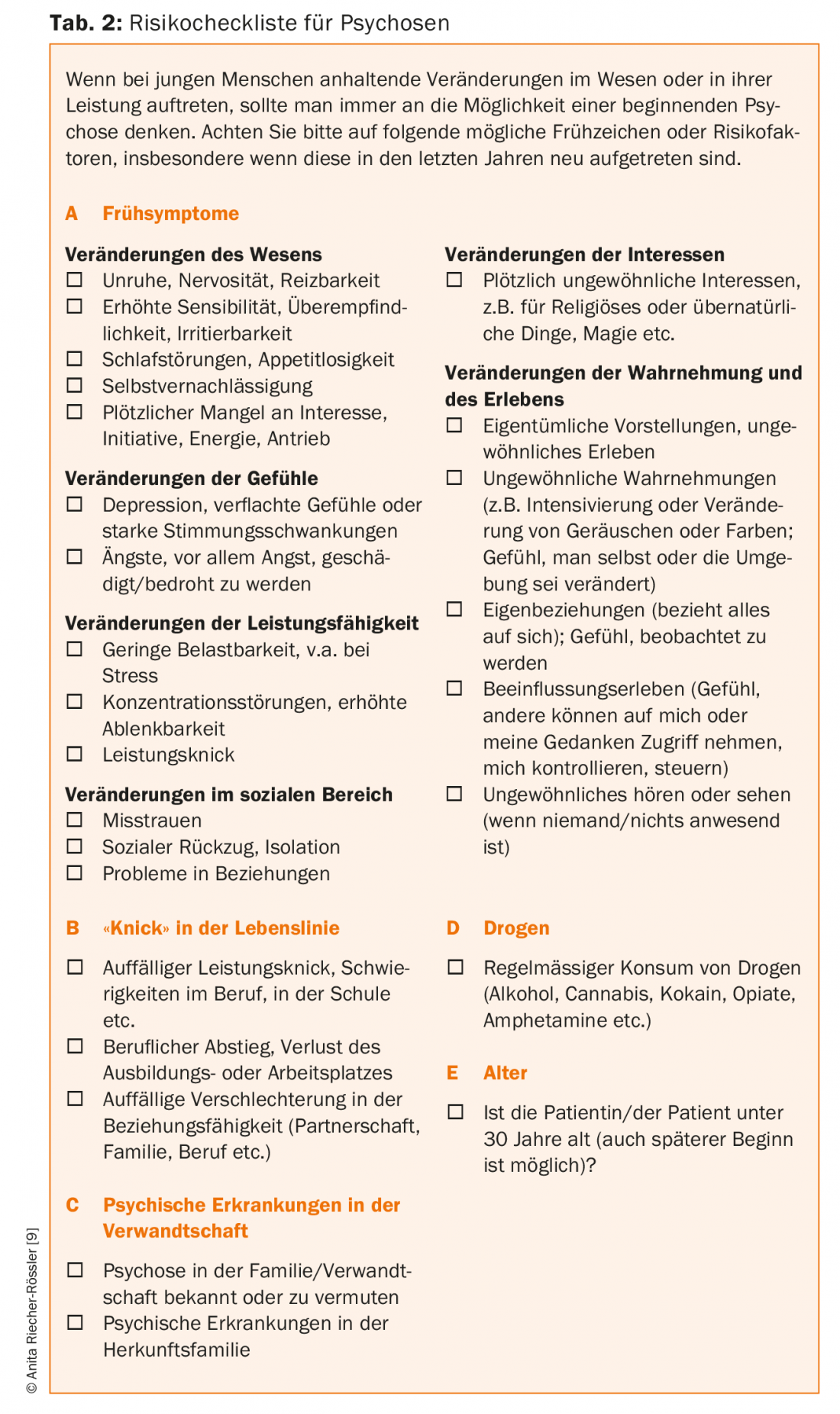

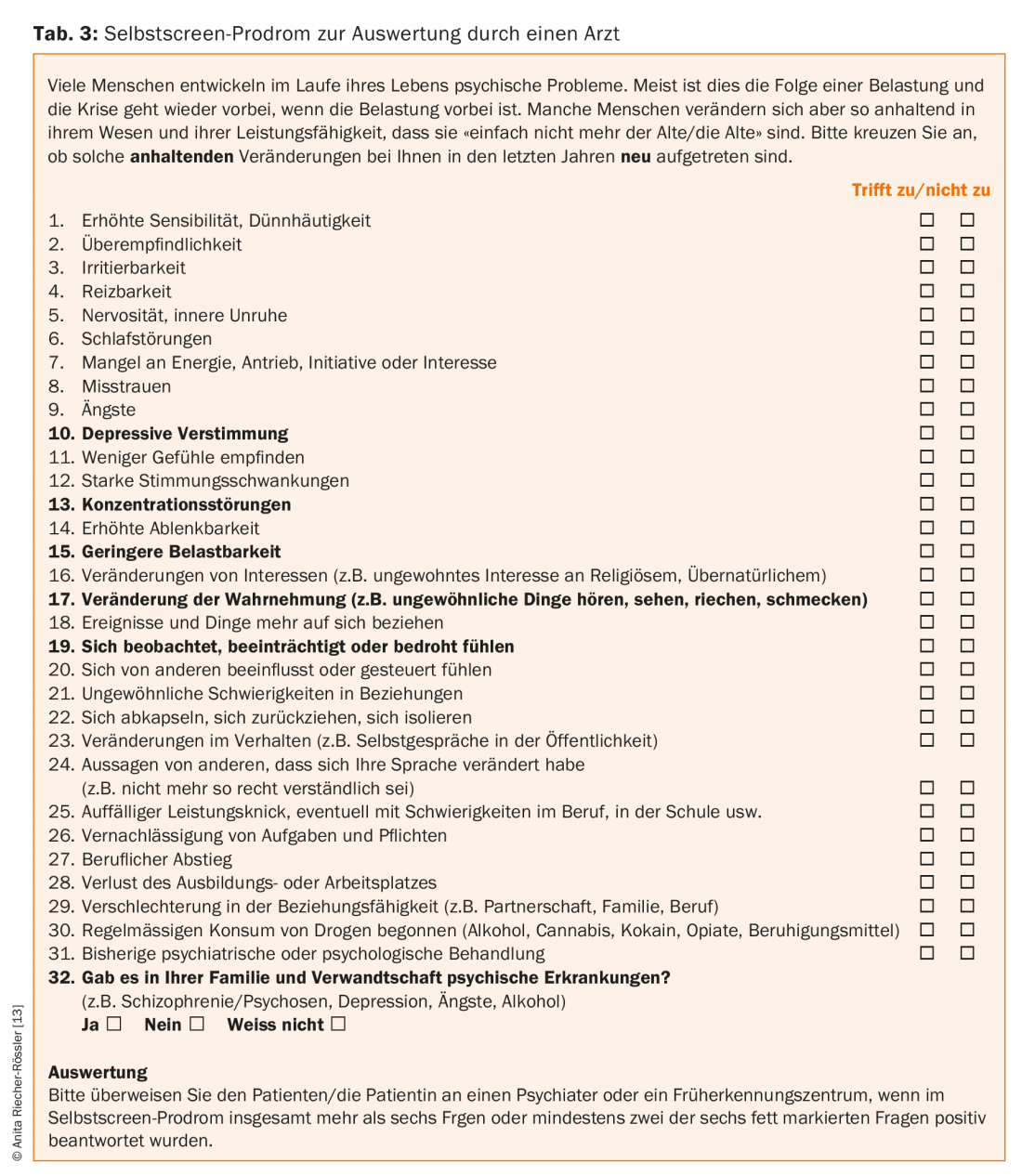

Risk checklists help established physicians identify symptoms early. The FePsy project developed the Risk Checklist (Table 2) to help primary care providers and practicing psychiatrists quickly and easily check whether an individual is at potential risk for psychosis. The risk checklist can be completed and evaluated by the physician. The self-screen prodrome (Tab. 3) is completed by the patient. If a person meets the risk criteria according to the checklist or self-screen syndrome, he or she should be referred to a psychiatrist or to a screening center.

The open explanation by the psychiatrist of the risk status as well as the explanation of the possible further course of the disease and the further prophylaxis and treatment options have top priority and require a certain tact. It is important to actively involve the patient and inform him or her about all further steps so that there is no feeling that something is happening behind his or her back, which can lead to mistrust [10,12].

Early Intervention

Early detection and intervention is primarily aimed at treating the presenting symptomatology. At the same time, it can prevent psychotic decompensation or chronification of the disease. Stage-specific treatment is offered as part of early intervention programs. This primarily includes the establishment of a sustainable therapeutic relationship, supportive discussions, psychoeducation, and cognitive-behavioral case management or cognitive behavioral therapy. In all cases, the therapeutic relationship with the patient and his relatives is of central importance [4,9,12].

For individuals at increased risk for developing psychosis, antipsychotic medication should not be used (yet) and interventions should be implemented cautiously. Psychotherapy has a high priority here. The use of medication should be exclusively syndrome-oriented, for example, to remedy sleep disorders or depressive moods. Measures to reduce stress and guidance on coping with stress are of great importance. Assistance with acute psychological stress can also be provided by social workers. In the case of a clearly diagnosed initial illness or psychotic decompensation, the use of antipsychotics is indicated. The patient should be offered supportive discussions, psychoeducation and, if necessary, neuropsychological training programs. Involving family members is key and can help reduce stress, ensure medication adherence, and reduce the risk of relapse.

Take-Home Messages

- The first signs of incipient psychosis typically appear in adolescence or early adulthood.

- Two simple screening questionnaires are available to the practitioner and patient for suspected psychosis risk.

- The outpatient screening diagnostics includes, in addition to clinical

- exploration also neuropsychological and laboratory parameters as well as imaging procedures.

- Early recognition and intervention for psychotic symptoms can positively influence the course and prevent chronification.

Literature:

- Riecher-Rössler A, McGorry P (Eds): Early detection and intervention in psychosis. State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Key Issues in Mental Health, Vol. 181. Basel, Karger; 2016.

- McGorry PD, et al: Intervention in individuals at ultra high risk for psychosis: a review and future directions. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70(9): 1206-1212.

- Van der Gaag M, et al: Preventing a first episode of psychosis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled prevention trials of 12 month and longer-term follow-ups. Schizophrenia research 2013; 149(1-3): 56-62.

- Schmidt SJ, et al: EPA guidance on the early intervention in clinical high risk states of psychoses. European psychiatry: the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists 2015; 30(3): 388-404.

- Fusar-Poli P, et al: Improving outcomes of first-episode psychosis: an overview. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association 2017; 16(3): 251-265.

- Riecher-Rössler A, Studerus E: Prediction of conversion to psychosis in individuals with an at-risk mental state: a brief update on recent developments. Curr Op Psychiatry 2017; 30(3): 209-219.

- Hauser M, et al: Neuropsychological test performance to enhance identification of subjects at clinical high risk for psychosis and to be most promising for predictive algorithms for conversion to psychosis: A Meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2017; 78(1): 28-40.

- Riecher-Rössler A, et al: Efficacy of using cognitive status in predicting psychosis: a 7-year follow-up. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 66(11): 1023-1030.

- Riecher-Rössler A et al: Prediction of psychosis by stepwise multilevel assessment -The Basel Fepsy Project. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2013; 81(5): 265-275.

- Schultze-Lutter F, et al: EPA guidance on the early detection of clinical high risk states of psychoses. European psychiatry: the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists 2015; 30(3): 405-416.

- Riecher-Rössler A, et al: The Basel Screening Instrument for Psychosis (BSIP):development, design, reliability, and validity. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2008; 76(4): 207-216.

- Riecher-Rössler A, et al: Early detection and early intervention in onset psychosis. Neurotransmitter 2015; 26(1): 50-54.

- Kammermann J, Stieglitz RD, Riecher-Rössler A: “Self-screen prodrome” – self-rating for the early detection of mental disorders and psychoses. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2009; 77(5): 278-284.

Additional literature can be requested from the authors.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(1): 3-8.