In COPD, two assumptions seem set in stone: The disease must be defined by a ratio of one-second capacity FEV1 to forced vital capacity FVC of less than 70% on spirometric examination (FEV1/FVC <70), and it affects older men who smoke cigarettes. The fact that this is not the whole truth has still not penetrated to everyone. Reason for a research group to formulate new definition criteria.

The Lancet committee headed by Prof. Dr. Daiana Stolz from the Department of Pneumology at the University Hospital Freiburg (D) and the Department of Pneumology at the University Hospital Basel questions the concepts of diagnosis and therapy of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), some of which are decades old [1]. The scientists formulate three key points to help in the approach to COPD in the future:

- New diagnostic criteria for COPD that go beyond spirometry

- A new classification of COPD subtypes 1-5 that goes beyond cigarette smoking.

- A new definition of exacerbation that goes beyond the need for drug therapy

COPD is a heterogeneous disease that results in numerous systemic consequences and comorbidities, which may develop differently from patient to patient. “That’s why we think the diagnostic criteria we use today are simply not good enough,” the pulmonologist explained. The main reason for this assessment is that the criteria have not changed for decades and are primarily based on spirometry after bronchodilation. However, he said, this is too limited to reflect the diversity of the pathophysiology of the disease. It is well known that spirometry is not sensitive for pathologic changes in early stage COPD, is overall underutilized or often misinterpreted, and furthermore is not predictive of symptoms.

The goal, he said, is to move the time of diagnosis from the average age of retirement to an age in the mid-30s to halt early respiratory changes and emphysematous destruction of the lung parenchyma and prevent subsequent organ failure. Currently, COPD would be diagnosed when organ damage is already irreversible, Prof. Stolz said.

She therefore argues for a broader definition to include airflow limitations detected by more sensitive pulmonary function tests and pathologic changes detected by imaging. Researchers believe that earlier detection of the disease can increase the possibility of effective therapy, identify the mechanisms responsible for the disease, and thus interrupt and reverse its progression.

New diagnostic criteria

For future diagnosis, the group presents three criteria to define COPD disease:

- Presence of respiratory symptoms

- Personal history regarding risk factors

- Presence of persistent limitation of airflow or ventilatory heterogeneity detected by spirometry or other pulmonary function tests, histology, or CT scan

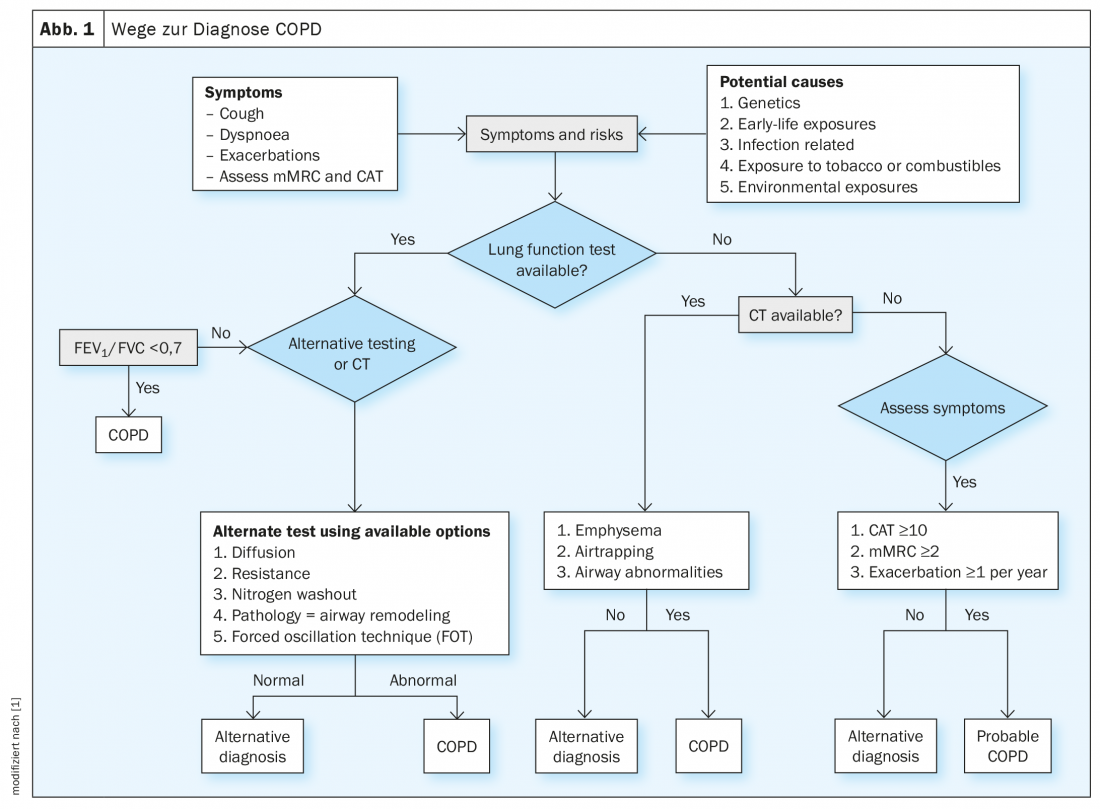

In clinical use, an initial assessment of symptoms and risk factors should be performed and, if available, a pulmonary function test should be performed. If obstruction is present in terms of FEV1/FVC <70, a diagnosis of COPD can be made; otherwise, alternative tests are available: Changes in diffusing capacity, resistance, nitrogen washout, pathology (airway remodeling), and forced oscillatory technique (FOT) can also diagnose COPD.

If a pulmonary function test is not available, CT may be considered as a diagnostic method: In case of emphysema, air trapping or airway abnormalities, COPD diagnosis is also possible (Fig. 1). If CT is not available and you only have symptoms, Prof. Stolz recommends using CAT ≥10, mMrc ≥2, and ≥1 exacerbation/year as a guide. “If these occur along with the appropriate symptoms, you can assume probable COPD.”

Subtype classification

COPD was once thought to be a disease of smokers, but it is now recognized that several other factors are important in the pathology. Depending on the risk factors associated with the development of the disease in a patient, a corresponding subtype can be assigned.

Those patients who do not smoke tend to be younger and have better lung function than those who develop their COPD because of their cigarette use. Also, not all show an accelerated decline in lung function with age, and about 50% of patients with COPD have a normal decline in lung function – but never reach the expected healthy peak in their lung function in early adulthood.

Different prognostic methods and therapeutic considerations can be applied depending on the individual pathophysiology of the affected person. As a result, the Commission proposes to view the disease as one with multiple potential courses over time that may arise from individual risk factors and accumulate over a lifetime, with different risk factors having greater or lesser importance. For example, indoor and workplace exposure is of greater importance than outdoor exposure. Diagnosis and treatment options must be considered adjusted accordingly.

Based on the predominant risk factor driving each disease, researchers propose a classification into 5 subtypes [2]:

- Type 1 – genetic COPD (e.g. α1-antitrypsin deficiency).

- Type 2 – early life events (e.g. childhood asthma).

- Type 3 – respiratory infections (e.g., childhood respiratory infections, TB- or HIV-associated COPD).

- Type 4 – Exposure related to smoking or vaping (e.g., tobacco, cannabis, secondhand smoke, including in-utero exposure).

- Type 5 – caused by environmental factors (e.g. indoor air pollutants, occupational exposure to vapors, gases, dusts, etc., smog).

Of course, patients may be affected by more than one subtype; it is suggested that the diagnosis be associated with the most important exposure. More data would need to be analyzed to determine exactly how subtypes relate to endotypes and how these in turn relate to phenotypes. The resulting findings will inform what type of therapy may be considered for the different subtypes.

Exacerbations

Researchers consider the current definition of exacerbation problematic because it does not take into account the underlying process of the event, as well as subtypes or the use of biomarkers for categorization. It can also lead to misdiagnosis and hinder progress in the field.

Prof. Stolz’s suggestion for a more effective definition is therefore: an exacerbation should be defined as an increase in cough, dyspnea, or sputum production plus at least one of the following: Increase in airflow limitation or ventilation heterogeneity, increase in airway or systemic inflammation, evidence of bacterial or viral infection-always in the absence of acute cardiac ischemia, congestive heart failure, or pulmonary embolism.

Such an objective definition could help improve standardized assessment and patient-specific treatment, he said. This approach is accompanied by standard investigations to be performed against a list of significant risk factors whenever a patient presents with an increase in respiratory COPD symptoms.

In addition, the Commission proposes to objectify the severity of exacerbation using specific criteria, based on the degree of clinical, biological, and physiological deterioration. The presence of any of these criteria (e.g., clinically significant hypoxemia, reduced alertness, cardiac problems) would be sufficient to define an exacerbation as severe. An overall severity score could then be calculated based on the total number of criteria met. The definitions for mild or moderate exacerbations, on the other hand, are no longer necessary, the expert concluded.

Source: Symposium: Towards elimination of COPD – Innovative views from the Lancet Commission on COPD; Presentation: Revisiting the diagnosis and classification of COPD. European Respiratory Society Congress, Barcelona, Sept. 6, 2022.

Literature:

- Stolz D, Mkorombindo T, Schumann DM, et al: towards the elimination of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a Lancet Commission. Lancet 2022; 400 (10356): 921-972; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01273-9.

- Brusselle GG, Humbert M: Classification of COPD: fostering prevention and precision medicine in the Lancet Commission on COPD. Lancet 2022; 400 (10356): 869-871; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01660-9.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2022; 4(4): 38-39.