Chronic venous leg conditions are common and often lead to chronic venous ulcers. Therapy is based on local treatment of the ulcer, therapy of chronic venous insufficiency and recurrence prophylaxis. The ulcer is primarily addressed with surgical debridement in most cases. This is followed by moist wound dressings applied by qualified professionals. Compression therapy is the cornerstone of chronic venous insufficiency therapy. The rehabilitation of the superficial venous system (truncal veins and perforators) serves to prevent recurrence. More modern methods such as endovenous ablation of truncal and perforating veins compete with classical varicose vein surgery and show encouraging results. Despite all therapeutic measures, the recurrence potential of this condition is high.

Half of the adult population shows stigmata of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI). The prevalence ranges from 2-7% in men and from 3-7% in women [1]. Up to 1% of the population in industrialized countries will experience a leg ulcer during their lifetime, the majority of which is venous in origin [2]. In addition to the long suffering of the patients, this also has a socio-economic aspect that should not be underestimated.

Etiology

Chronic venous ulcer (CVU) represents a heterogeneous group of skin defects, which are triggered by chronic venous hypertension and consecutive deteriorated microcirculation. Etiologically, primary and secondary causes are distinguished. Primary venous changes are characterized by etiologically unidentifiable mechanisms of chronic venous dysfunction, most commonly manifesting in an insufficient superficial venous system. Secondary venous pathologies are mainly post-thrombotic or post-phlebitic, less commonly post-traumatic.

Reflux alone is responsible for primary CVI, whereas secondary CVI usually involves a combination of obstruction and reflux [3]. Pathophysiologically, both changes have superficial venous hypertension in common. Patients with combined pathology of obstruction and reflux have the highest incidence of skin lesions and chronic ulcers [4]. An ulcer is called chronic if it does not heal within six weeks [4].

Diagnostics

The diagnosis of chronic venous ulcer is based on the clinical picture supported by further examinations. The distinction from an arterial ulcer is very important. If the pain is severe, a cause other than venous should be considered as a differential diagnosis.

The typical CVU is not painful and is located in the medial malleolus. Characteristic of a venous genesis of the ulcer are itching, burning, muscle cramps, swelling, heaviness or “restless legs”. Inspection reveals varices, telangiectasias, edema, skin coloration changes, corona phlebectaticae, and possible lipodermatosclerosis [5]. In contrast, arterial ulcer often presents with pain, is localized to the lateral malleolus, and is associated with intermittent claudication. The suspected diagnosis can be corroborated with measurement of the ankle-brachial index (ABI).

Venous diagnostics: Color-coded duplex sonography has become established for venous diagnostics. It is safe, noninvasive, cost-effective, and reliable [6]. There is widespread agreement on the assessment of reflux in the superficial venous system. In contrast, the question of when a perforating vein should be considered insufficient is controversial. The literature lacks a defined standard. Most authors use a flow directed toward the surface of ≥500 msec as a criterion for perforator vein insufficiency [5]. Other studies consider the diameter of the perforating vein to be relevant [7, 8]. Yamamoto et al. were able to show that insufficient perforating veins had a significantly larger diameter than sufficient perforators (3.6±0.9 mm versus 2.6 ±0.9 mm) [8]. Accordingly, in the guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum, a diameter of ≥3.5 mm is considered pathological [7].

Classification

Classification of CVI can be done according to the simple Widmer classification [9]. Stage 1 is characterized by reversible edema and corona phlebectatica paraplantaris. In stage 2, edema persists and various skin changes such as hemosiderosis, purpura, dermatosclerosis, lipodermatosclerosis, atrophie blanche (Fig. 1), stasis eczema , and cyanosis are seen. The stage 3 according to Widmer describes CVI with ulcus cruris.

Fig. 1: Chronic venous ulcer in a 63-year-old female patient with marked atrophy blanche. No spontaneous healing under consistent compression therapy

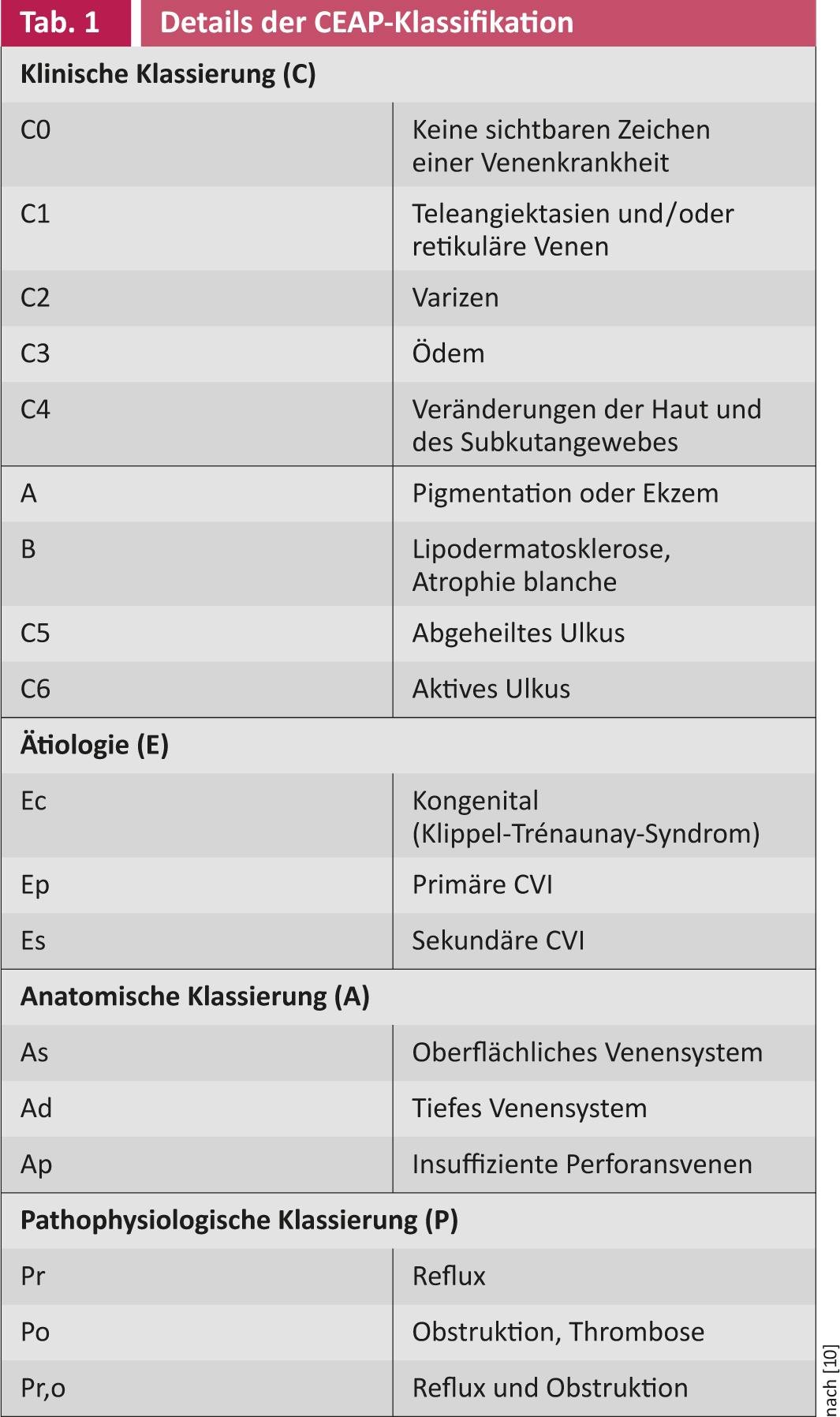

The much more precise and internationally accepted classification is the CEAP classification(Tab. 1) [10]. The basis of CEAP classification is based on a description of clinical changes (C), etiology (E), pathologic anatomic venous changes (A), and underlying pathophysiology (P). According to the CEAP classification, stages C5 and C6 are particularly relevant in the context of chronic ulcers.

Therapy

Treatment of CVU is based on three pillars: local treatment of the ulcer, treatment of CVI, and recurrence prohylaxis.

Local therapy: Local wound treatment usually begins with surgical debridement to remove devitalized tissue and fibrin film (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Tangential surgical debridement with the hand dermatome.

This treats the usually pre-existing “low grade” infection and improves the conditions for wound healing. Thereafter, occlusive dressings, e.g. hydrocolloid dressings, hydrogels or alginates are indicated. They have an autolytic effect, which helps to clean the wound, and keep the wound environment moist. Wound dressings with ionized silver as the active ingredient are designed to contain bacterial colonization. In a randomized trial (VULCAN Trial), no positive effect of the silver-containing products was found in terms of wound healing rate and time to healing, which is why their routine use is not recommended [11].

A wound with a reduction in area of at least 40% after three weeks of adequate wound treatment is very likely to heal completely quickly without a change in therapy [14]. To accelerate wound healing or for definitive closure, split-thickness skin grafting (Fig. 3 and 4), which should be applied with a vacuum-assisted system, as this significantly increases the accretion rate [12]. As an alternative to split-thickness skin coverage, modern wound treatment methods are available (autologous skin equivalents from keratinocytes [Epidex®], cultured allogeneic skin equivalents from fibroblasts and keratinocytes. [Apligraf®], layers of extracellular matrix [Oasis®], platelet-enriched fibrin [Vivostat PRF®], growth factors, etc.). These methods should be considered if wound area reduction is less than 40% after three weeks [13, 14]. Randomized studies comparing these products with split skin coverage or spontaneous healing rate are largely lacking.

Fig. 3: Split skin graft

Fig. 4: Healed ulcer with healed split skin

Therapy of CVI: Compression therapy has proven effective for the therapy of CVI. It leads to a significant increase in the cure rate [15, 16]. In an initial phase lasting about three weeks, decongestion is the primary goal. This is done with advantage by compression bandages. After this phase, compression stockings should be preferred over compression bandages because more ulcers heal in less time with stockings [15]. The reasons for this are not clearly demonstrated. Compression therapy should have a pressure of 40 mmHg, as this achieves a higher healing rate than 20 mmHg (equivalent to compression class 2 to 3) [2, 16].

In the treatment of postthrombotic syndrome, endovascular therapy of the iliac veins by stenting is useful at best [23]. Reconstruction of the deep venous system by valve reconstruction or transplantation is reserved for special situations.

Recurrence prophylaxis: Due to the high recurrence rate (30% after 1 year, 78% after 2 years [17]), recurrence prophylaxis must be given high priority. Because treatment of an insufficient superficial venous system and insufficient perforating veins leads to a significant reduction in the recurrence rate [7, 18, 19], they are of central importance.

Insufficient truncal veins should be treated by crossectomy and stripping of the great saphenous vein to approximately knee joint level or ligation and stripping of the parietal saphenous vein (evidence level 2B and 1B, respectively) [7]. Alternatively, endovenous ablation using radiofrequency or laser may be considered [19]. Endovenous therapy of the truncal veins and also the perforating veins has gained massive importance in recent years and shows very good results [20]. In the future, it will compete fiercely with traditional varicose vein surgery. Sclerotherapy of the insufficient truncal veins seems to be inferior to surgical and endovenous therapy [20].

Data on the treatment of insufficient perforators are currently insufficient because no randomized studies are available. O’Donnell, in a systematic analysis of guidelines, recommends that the primary focus of treatment for reflux should be the truncal veins [21]. Large insufficient perforators (>3.5 mm) with large volume reflux in the ulcer area can be treated. Open surgical procedures, endoscopic perforator ligation (“Subfascial Endoscopic Perforator Surgery”, SEPS) and also percutaneous endovenous ablations (thermal or chemical) are possible. There are no randomized studies on the value of these three methods. The Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines recommend treating insufficient perforators in the area of an ulcer at stage C5 and C6 [7] using surgical ligation, SEPS, ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy, or thermal ablation, especially if conservative therapy for CVU fails. Lawrence et al. showed that in non-healing CVU, endovenous ablation of at least one perforating vein resulted in 90% of ulcers healing [22].

Forecast

Even when an ulcer has healed, the recurrence rate is very high, up to 78% [17]. In patients in whom surgical repair of the varices is performed after healing in addition to conservative therapy with compression, the recurrence rate is significantly lower than with compression alone (31 vs. 56%) [18]. This is true not only for patients with extrafascial venous insufficiency, but also for patients with combined extrafascial and deep venous reflux [18].

Thomas Lattmann, MD

Literature:

- Callam MJ: Br J Surg 1994; 81(2): 167-173.

- O’Meara S, Cullum NA, Nelson EA: Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; (1): CD000265.

- McAree BJ, Berridge DC: Phlebology 2010; 25(suppl 1): 20-27.

- Abbade LP, Lastória S: Int J Dermatol 2005; 44(6): 449-456.

- Gloviczki P: J Vasc Surg 2011; 53(5 Suppl): 1S.

- Coleridge-Smith P, et al: Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006; 31(1): 83-92.

- Gloviczki P, et al: J Vasc Surg 2011; 53(5 Suppl): 2S-48S.

- Yamamoto N, et al: J Vasc Surg 2002; 36(6): 1225-1230.

- Widmer LK, et al: Langenbeck’s Arch Chir 1978; 347: 203-207.

- Porter JM, Moneta GL: J Vasc Surg 1995; 21(4): 635-645.

- Michaels JA, et al: British Journal of Surgery 2009; 96(10): 1147-1156.

- Körber A, et al: Dermatology 2008; 216(3): 250-256.

- Gelfand JM, Hoffstad O, Margolis DJ: J Invest Dermatol 2002; 119(6): 1420-1425.

- Phillips TJ, et al: J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 43(4): 627-630.

- Amsler F, Willenberg T, Blättler W: J Vasc Surg 2009; 50(3): 668-674.

- O’Meara S, et al: Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 11: CD000265.

- Mayer W, Jochmann W, Partsch H: Wien Med Wochenschr 1994; 144(10-11): 250-252.

- Gohel MS, et al: BMJ 2007; 335(7610): 83.

- Harlander-Locke M, Let al: J Vasc Surg 2012; 55(2): 458-464.

- Rasmussen LH, et al: Br J Surg 2011; 98(8): 1079-1087.

- O’Donnell TF: Phlebology 2010; 25(1): 3-10.

- Lawrence PF, et al: J Vasc Surg 2011; 54(3): 737-742.

- Rosales A, Sandbaek G, Jorgensen JJ: Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010; 40(2): 234-240.

CARDIOVASC 2013, no. 4: 14-17.