The treatment of breast carcinoma has changed significantly in recent years. Individualized therapy management that addresses the particular specificity of the breast carcinoma is now the focus.

The treatment of invasive breast carcinoma has changed significantly in recent years and decades. Whereas in the past the focus was on surgical therapy and a large proportion of patients were additionally treated with chemotherapy despite extensive surgery, today we are increasingly able to adapt our therapy offers to the individual disease of the patient. Side effects of drug therapies and surgical morbidity are thus kept as low as possible – of course with consistently good or improved chances of recovery. In the following, without claiming to be exhaustive, we would like to take a closer look at the changing role of surgery and chemotherapy in the therapeutic concept.

North American surgeon William S. Halsted first described mastectomy as an effective treatment for non-metastatic breast cancer in 1882. And although the English physician G. Beatson also made the observation as early as the end of the 19th century that a bilateral adnexectomy could lead to a reduction in the size of breast tumors and metastases, breast cancer was treated exclusively surgically and always by mastectomy for the next 100 years. It was not until the late 70s of the 20th century that breast-conserving therapy in combination with radiation was developed. Sentinel lymphonodectomy was introduced in the 1990s and has been established as the standard treatment for clinically and imaging negative axillary lymph nodes since the end of the last millennium. At the same time, breast cancer began to be recognized not only as a local disease, but also as a systemic disease. Patients were treated not only surgically, but additionally with medication. In 1978, the first anti-hormonal therapy, tamoxifen, was launched in the U.S., and in 1998, trastuzumab became the first monoclonal antibody to be approved by the FDA, initially in the metastatic setting.

And this is more or less the situation as it was at the turn of the millennium. According to international guidelines, breast cancer should be treated primarily surgically, with breast conservation whenever possible. In cases of hormone receptor positivity, anti-hormonal therapy and adjuvant chemotherapy, if necessary, have been recommended following surgery [1]. In the USA, women under 70 years of age have been advised to undergo chemotherapy if the tumor size exceeds 1cm, regardless of nodal status [2].

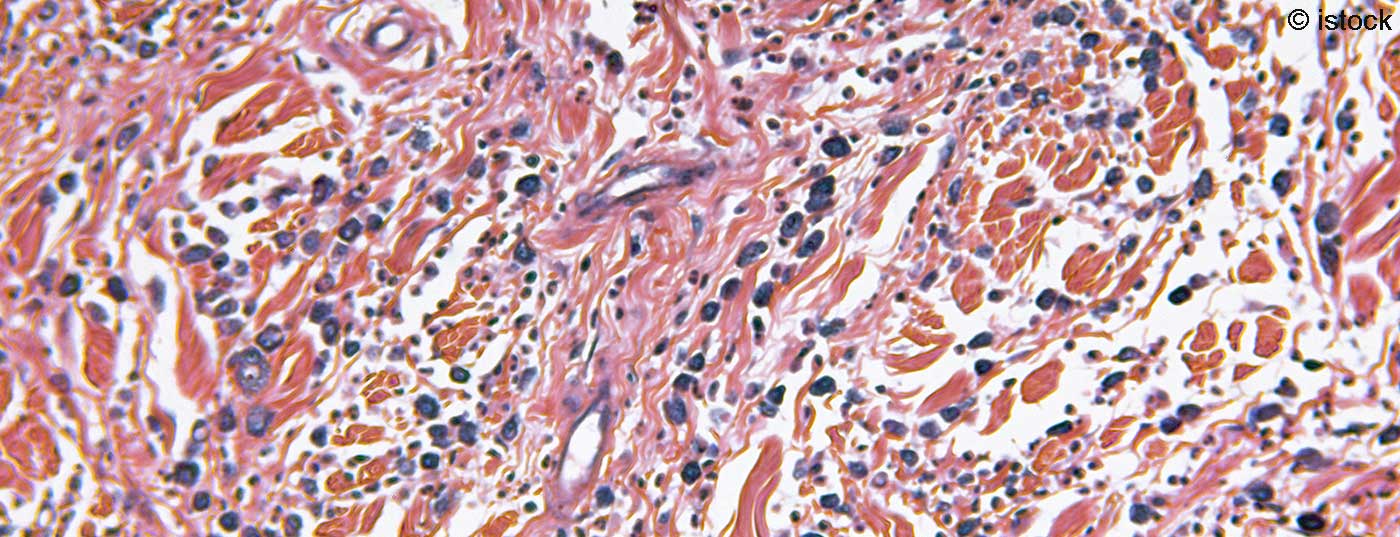

Different tumor biology characteristics of breast cancer.

Over the last two decades, there has been a growing body of knowledge that there are different “breast cancer types”, which also need to be treated differently. Irrespective of age, menopausal status and nodal status, clinicopathological factors have been defined since the turn of the millennium, which allow us to form risk groups and to adapt therapy recommendations individually to these risk groups. The aim is to avoid unnecessary chemotherapy, which is harmful to patients, and to define groups of patients who are adequately treated with anti-hormonal therapy alone.

Patients with so-called luminal A tumors (hormone receptor positive, Her2 new negative, low Ki 67) have a low risk of recurrence and metastasis. Chemotherapy can be omitted in these patients, except in cases of extensive Lk involvement. In patients in the high-risk group (hormone receptor negative, Her2 new positive), chemotherapy (in the case of Her2 new positivity in combination with antibody therapy) is essential except in very small tumors. In Her2 newly positive tumors, however, chemotherapy may at least be reduced in favor of antibody therapy. Instead of “classical” anthracycline- and taxane-containing chemotherapy, women with small, Her2 newly positive, node-negative breast carcinoma were treated with chemotherapy with “only” 12 bursts of Taxol in combination with Herceptin over 1 year in the APT Trial [3]. With a very good side effect profile, overall survival (OS) data were excellent. In this patient population, therapy with taxol and Herceptin may represent a well-tolerated alternative to the classic chemotherapy regimens, which have more side effects.

It remains difficult to recommend therapy for the intermediate risk group (suboptimal hormone receptor expression, G2/3, high CI 67, 1-3 affected lymph nodes). Here, gene expression analyses (e.g. Endopredict®, OnkotypeDX®) can facilitate the therapeutic decision for or against chemotherapy. The TailorX study published in 2018 [4] demonstrated that node-negative patients with hormone receptor positive, Her2 newly negative breast carcinomas and a median recurrence score of 11-25 on the OncotypeDX test did not benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. The results of the RxPonder Trial, which investigates the same question for patients with 1-3 affected lymph nodes, are pending.

Surgical treatment in the adjuvant therapy situation

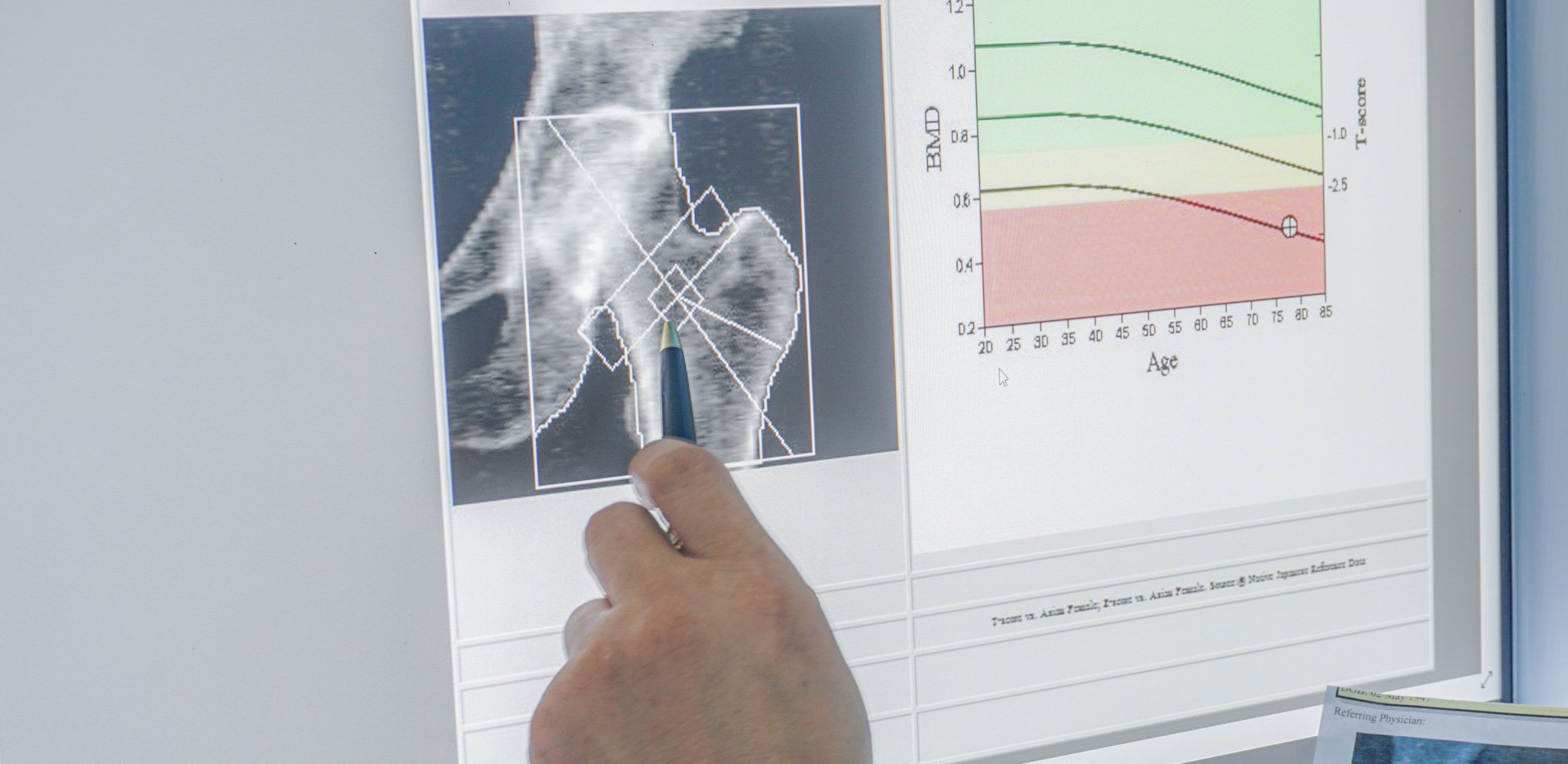

With the introduction of breast-conserving therapy and sentinel lymphonodectomy, surgical radicality had already decreased significantly by the end of the last millennium. However, even patients who “only” receive a sentinel lymphonodectomy suffer from lymphedema of the arm in about 5-15%, which can have a relevant impact on the quality of life. In addition, breast lymphedema may occur in breast conservation, especially with the use of extensive oncoplastic displacementplasty and exacerbated by postoperative radiation therapy. The ACOSOG-Z-0011 trial, published in 2011, showed that women with breast carcinoma smaller than 5 cm and 1-2 affected sentinel lymph nodes may not require axillary dissection if the patient receives postoperative radiotherapy and “guideline appropriate” systemic follow-up [5]. The 10-year data were presented at ASCO 2016. No significant differences were seen in either axillary recurrence rate (0.5% in patients with axillary dissection vs. 1.5% in patients with SLN) or overall survival (83.6% vs. 86.3%) [6]. The study can be described as “practice changing” at least in the USA and in Central Europe – this despite known methodological deficiencies (in particular, the insufficiently documented irradiation protocols should be mentioned) – and was quickly integrated into everyday life.

New approaches even go far beyond this. The German INSEMA Trial (7,8) randomizes patients with T1 and T2 tumors with clinically and imaging negative axillary lymph nodes into two groups in a 1:4 ratio: One group receives sentinel lymphonodectomy, as is standard, and the other group receives no axillary surgery at all. The results remain to be seen, but it may be possible in the future to completely eliminate surgical intervention in the axilla in a selected patient population.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) and its impact on surgical treatment.

Whereas 10 years ago most chemotherapies were administered adjuvantly, today neoadjuvant therapy is increasingly common. The neoadjuvant setting provides an in vivo test of response to therapy. Neoadjuvant therapy can increase the rate of breast-conserving therapies because resection margins are determined by the imaging and clinical postneoadjuvant extent of the tumor [9, as cited in 6]. And axillary surgery may also be reduced. 20-40% of nodal-positive patients prior to initiation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy convert to clinically and imaging negative nodal status during therapy [6]. Until three years ago, these patients were still treated with axillary dissection due to an excessively high false-negative rate and an inadequate detection rate of the sentinel lymph node [10, 11]. In 2016, the publication of the concept of “targeted axillary dissection” led to a paradigm shift [12]. Histologically confirmed lymph node metastases are marked with a clip prior to initiation of chemotherapy and must necessarily be removed as part of sentinel lymphonodectomy after completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. If at least 3 sentinel lymph nodes are removed as part of this therapeutic concept, the false-negative rate can be reduced to an acceptable level. However, it is not easy to find the clipped lymph nodes intraoperatively. The SenTA study [13] initiated in Germany is testing the feasibility and practicability of the concept of “targeted axillary dissection”.

The concept of “postneoadjuvant chemotherapy”.

While nodal status used to be the most important prognostic factor, pathologic complete remission (pCR), defined as tumor freedom in breast and lymph nodes after neoadjuvant therapy, is now increasingly important. In tripel-negative and HER2/neu-positive breast carcinomas, achievement of pCR may be considered a surrogate marker for prolonged disease-free survival (DFS) and prolonged overall survival (OS) [14]. This has led to the concept of “postneoadjuvant therapy.” In the Japanese CreateX trial, women in whom pCR could not be achieved received “postneoadjuvant chemotherapy” with Xeloda for 6 months. In particular, the subgroup with tripel-negative breast carcinoma had significantly improved disease-free survival [15]. Data from the Katherine study caused a stir at the 2018 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. Postneoadjuvant administration of T-DM1 (a hybrid of the antibody trastuzumab and the chemotherapeutic agent Emtansine) improved DFS in patients with Her2 newly positive breast cancer who had failed to achieve pCR with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and Herceptin. The data was published in 2019 [16] and is already being put into practice at many clinics.

Conclusion

In the last two decades, it has been possible to individualize the therapy of early breast carcinoma. It was recognized that under the umbrella term “breast cancer” different entities are gathered, which require different therapeutic strategies. This makes the treatment gentler and more effective, but also significantly more complex. The newly developed drugs in particular are not only expensive, they also require physicians who are trained and specialized in their use. The more complex processes require a corresponding, also cost-intensive infrastructure.

Take-Home Messages

- There are different “breast cancer types”, which are also treated differently

- Tumor biological characteristics are responsible for the classification into different risk groups. These are independent of the patient’s age, menopausal status, and also nodal status

- The aim of the treatment strategy must be to reduce the therapy-related morbidity for the patient to a minimum with an equivalent (or even improved) chance of recovery.

- In this context, surgical treatment in particular, which has been the main treatment for decades, takes on a new significance in the overall context of therapeutic options.

Literature:

- Guideline for adjuvant systemic therapy (AST) of breast carcinoma in women. Switzerland. Ärztezeitung/Bulletin des médecins suisses/Bolletino dei medici svizzeri 2003; 84: 38.

- Adjuvant Therapy for Breast Cancer, National Institutes of Health, Consensus Development Conference Statement, 2000.

- Tolaney, et al: Adjuvant Paclitaxel and Trastuzumab for Node-Negative, HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 134-141.

- Sparano, et al: Adjuvant Chemotherapy Guided by a 21-Gene Expression Assay in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 111-121

- Giuliano AE, et al: Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasivebreast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2011; 305: 569-576.

- Kühn T: Therapy in early breast carcinoma, Chapter 5: Local therapy: surgery. Colloquium Senologie 2017; 1018: 109-117.

- Intergroup Sentinel Mamma (INSEMA) Trial – GBG 75: Comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy versus no sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with early invasive breast cancer and planned breast-conserving surgery: a prospective randomized surgical trial.

- Reimer T, et al: Restricted axillary staging in clinically and sonographically nodenegative early invasive breast cancer (c/iT1-2) in the context of breast conserving therapy: first results following commencement of the Intergroup-Sentinel-Mamma (INSEMA) Trial. Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2017; 77: 149-157.

- Bossuyt V, et al: Recommendations for standardized pathological characterization of residual disease for neoadjuvant clinical trials of breast cancer by the BIG-NABCG collaboration. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 1280-1291.

- Kuehn T, et al: Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 609-618.

- Boughey JC, et al: Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer: the ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 310: 1455-1461.

- Caudle AS, et al: Improved axillary evaluation following neoadjuvant therapy for patients with node-positive breast cancer using selective evaluation of clipped nodes: implementation of targeted axillary dissection. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 1072-1079.

- SenTa study, GBG: Prospective, multicenter registry study of the frequency of use and feasibility of targeted axillary lymph node excision (targeted axillary dissection) after punch biopsy and clip marking in primary breast carcinoma with clinically suspicious lymph nodes.

- Cortazar P, et al: Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet 2014; 384: 164-172.

- Masuda N, et.al Adjuvant Capecitabine for Breast Cancer after Preoperative Chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 2147-2159.

- von Minckwitz G: Trastuzumab Emtansine for Residually Invasive HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2019; 380:617-628.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2019; 7(4): 8-10.