In the treatment of chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), effective control of inflammation is fundamental, and an early switch to novel therapies to avoid long-term complications is also emphasized in guidelines. However, biologics are not only expensive, but can also be a burden for the patient. Many people therefore wish to temporarily stop therapy. The opportunities and risks of a break have now been examined in a review.

The treatment of inflammatory bowel disease was revolutionized with the introduction of biologics two decades ago. Today, numerous biologics and increasingly small molecules are approved for the treatment of IBD.

In the UK, around 30% of Crohn’s disease (MC) and 15% of colitis ulcerosa (CU) patients are currently being treated with novel therapies, write Dr. Christian Selinger of Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust and colleagues. The choice of therapeutics for moderate to severe IBD has increased and includes anti-tumor necrosis factor biologics (TNF; infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab$ and certolizumab**), anti-integrin biologics (vedolizumab), anti-IL-12/23 biologics (ustekinumab), anti-IL-23 biologics (risankizumab**), mirikizumab$, oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors (tofacitinib$, filgotinib$ and upadacitinib) and S1P inhibitors (ozanimod$).

$ UC only

** CD only

Good control of the inflammation, not just the symptoms, is associated with a lower frequency of exacerbations and a reduced need for hospitalization or surgery. As all novel therapies suppress the immune system, there is an increased risk of infection, which is higher in those receiving combination therapy with anti-TNF and immunomodulators. There is also an increased risk of malignant diseases (skin cancer and lymphomas, especially in connection with TNF and thiopurines) with immunosuppressive therapies. In a study not related to IBD, tofacitinib was associated with an increased risk of malignancies. As the authors explain, despite the lack of evidence, the regulatory authorities assume that this could be a class effect for all JAK inhibitors.

Opportunities and risks of stopping biologics

Although there are no data to date that indicate an increased risk of malignant disease with vedolizumab and ustekinumab, meaningful observational data often require a decade or more to demonstrate such associations, the authors explain. In addition, there are concerns about the associations of JAK inhibitors with serious cardiovascular events and particularly venous thromboembolism, especially those that inhibit both JAK1 and JAK3. Dr. Selinger and his team analyzed the risk of relapse after discontinuation of modern therapies and the chance of responding again in the event of an exacerbation after discontinuation.

The reduction of side effects is the most important potential benefit of discontinuing advanced IBD therapies, the reduced risk of infections, malignancies, cardiovascular or thromboembolic events is an important clinical factor. A break from immunosuppressive therapy can reduce the number of minor infections or allow patients to travel to areas that would otherwise not be possible due to infection risks (e.g. TB) and vaccinations (e.g. yellow fever or other live vaccines). Another advantage of the deduction is the cost. Although the emergence of biosimilars has significantly reduced prices in some countries, the overall cost of advanced therapies remains high.

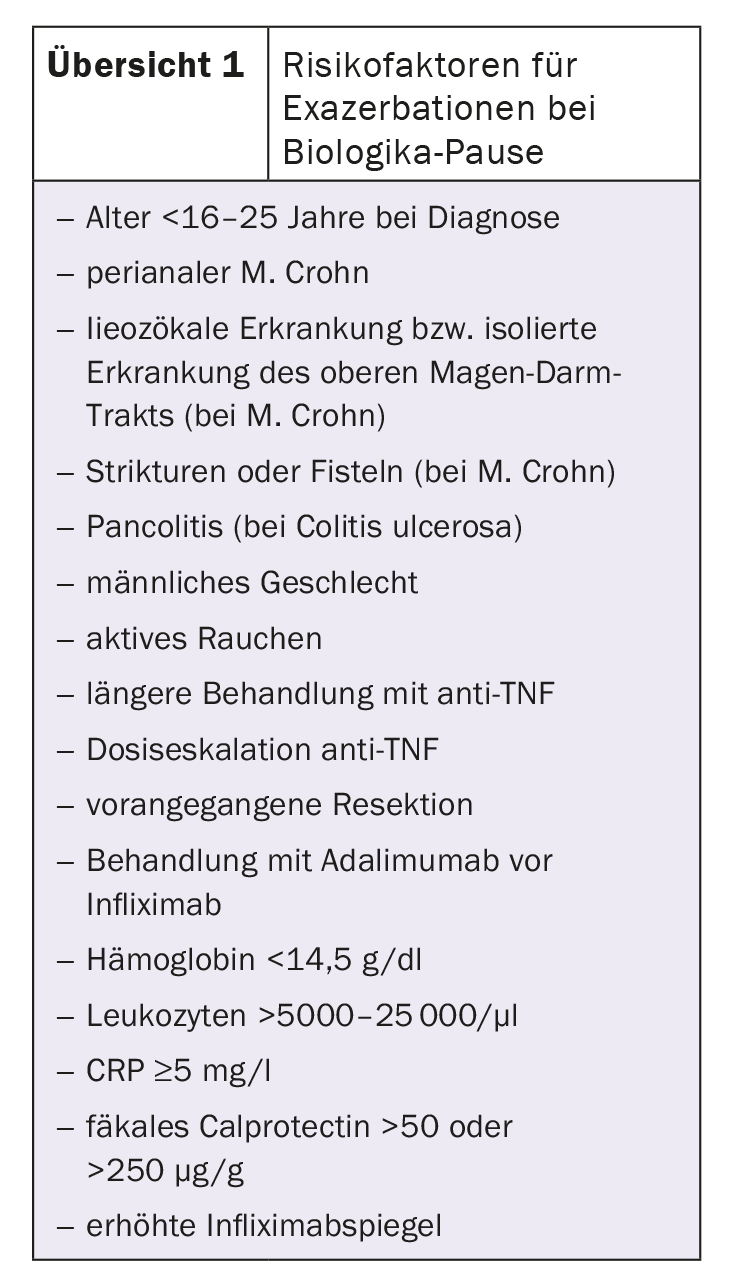

The main risks of discontinuing treatment include an exacerbation of the disease with the potential risk of hospitalization or surgery. Most of the available data concern anti-TNF, in particular infliximab. The data on non-TNF biologics and JAK inhibitors are very sparse. The available randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses show that the discontinuation rate of anti-TNF biologics is around 40% after one year and 50% after two years. Many patients need to be treated again, but after 3-5 years the rate seems to be stable. The authors summarize a number of risk factors for a relapse after a break from biologics (overview 1) .

Chance of a renewed response

The data on the renewed response in the event of a relapse after discontinuation are limited to infliximab. Most published studies indicate that 70-90% of patients who resume treatment with infliximab also achieve clinical remission. According to Selinger et al. it therefore makes sense to try to resume treatment with the same active substance that was previously discontinued. However, not every patient responds again and achieves remission when treatment is resumed, which should be pointed out in the doctor-patient consultation. In addition, it is important to consider the risk of infusion reactions after resumption of treatment, even if this is generally low at around 9%.

Small molecules are not associated with the formation of antibodies against drugs. This risk exists with cyclical treatment with biologics, which in turn increases the risk of anaphylactic reactions and reduced efficacy in subsequent treatment cycles. Small molecules (tofacitinib, filgotinib, upadacitinib and ozanimod) could therefore – at least theoretically – be more suitable for cyclic or episodic treatment, as a lack of efficacy due to the formation of antibodies against the drug is avoided. However, recovery of response to treatment is complex and other factors may continue to influence disease control during exacerbations after treatment has ended. There is currently little data available to investigate these scenarios, so all considerations are based on theory rather than evidence, the authors explain.

No de-escalation without deep remission

Dr. Selinger and his colleagues suggest considering de-escalation of treatment in patients taking anti-TNF biologics in stable clinical remission and whose fecal calprotectin is in remission. Deep remission should be confirmed by endoscopy in patients with colorectal disease or isolated terminal ileal disease, and small bowel examination with ultrasound, MRI or CT should be performed in patients with small bowel disease. Patients without deep remission should not be offered de-escalation. All decisions should be made jointly by the physician and patient based on a comprehensive consultation about the potential benefits and risks of the anti-TNF biologic discontinuation plan.

The patient’s individual circumstances and phenotypic situation (rectal disease, extraintestinal symptoms) as well as previous treatment (first-line biologic, combination therapy with an immunomodulator) should be taken into account. If IBD symptoms occur, a clinical and endoscopic follow-up examination should be carried out in good time.

Given the current lack of evidence for therapies other than anti-TNF biologics, the proposed algorithm is limited to these agents. It is conceivable that the evidence will be sufficient to include other drugs in the future.

Take-Home-Messages

- Many patients with IBD receive long-term advanced therapies.

- Treatment breaks can enable patients to reduce their risk of infections, malignancies, cardiovascular or thromboembolic events.

- The risk of relapse after discontinuation of the anti-TNF is around 38% after 12 months.

- Most patients respond again after renewed treatment with anti-TNF.

- Data on other novel therapies are not yet available.

Literature:

- Selinger CP, Rosiou K, Lenti MV: Biological therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: cyclical rather than lifelong treatment? BMJ Open Gastroenterology 2024; 11: e001225; doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2023-001225.

GASTROENTEROLOGY PRACTICE 2024; 2(1): 22-23