General measures such as weight reduction and more exercise are mentioned as cornerstones in all guidelines for hypertension treatment. Nevertheless, the general measures are still in the shadows. Another problem in the treatment of hypertension is nonadherence, which is about 40%. In this difficult environment, a model for patient motivation in hypertension therapy was developed at the University of Bern.

Satisfaction is a basic human need that is determined by internal and external circumstances. The perception is intra- and interindividual variable and therefore often not congruent for patient and caring physician. Especially the interindividual difference in perception can be described by different test systems, but most of them are not suitable for practical use [1]. If one wants to conclude from the physician satisfaction to the patient satisfaction and vice versa, sometimes considerable discrepancies arise, also just by different involved physicians.

Well documented are patient-oriented forms of information, which – if understandable – are accepted and positively associated by a large number of patients [2]. Interestingly, it was shown that by using a simple transactional decision support tool, patient satisfaction could be increased. In addition, decisions that the patient had consciously made were less likely to be regretted and doubted. Global cardiovascular disease risk was not negatively affected, although the observation period and number of participants were not clearly designed for this purpose [3].

Decision support for better doctor-patient communication

Just recently, a Cochrane meta-analysis of 115 studies (34,000 participants) analyzing patient decision aids was able to show a whole range of influences. These decision-making tools have the effect of increasing patients’ knowledge of possible options, reducing their decision conflict, improving their sense of being informed, and reinforcing their sense of living personal values [4]. The better-informed patients can take a more active role in the decision-making processes that affect them and actively assess risks if probabilities of occurrence are provided with the decision aids. This improves doctor-patient communication. Very importantly, it was observed that no negative effects on health variables were apparent and even the number of surgical procedures could be reduced while maintaining patient satisfaction.

Nevertheless, a number of questions remain unanswered. Can adherence really be improved with such systems? Are the interventions cost-effective? Can less educated people also benefit from such an intervention? How detailed must such decision aids be structured?

The German system ARRIBA

One example of a decision support tool is the ARRIBA system, which is funded by several university institutes of general medicine in Germany with support from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (www.arriba-hausarzt.de). It is designed to promote participatory decision making in cardiovascular risk prevention using a consultation-based decision aid for general medical practice. Based on the Framingham data, an exciting electronic tool has been developed over time:

A stands for the joint definition of the task by the physician and the patient;

R for the patient’s subjective risk assessment;

R for an objective visualized risk assessment by the physician, adapted to the patient’s educational level;

I for information on non-drug and drug prevention and treatment options;

B for the evaluation of the individual measures in the context of the patient’s life situation;

A for the resulting arrangement to result in a feasible plan within a clearly defined time frame.

Improving motivation in hypertension treatment

Although general measures are included in all guidelines as a cornerstone of hypertension treatment, they have a shadowy existence (e.g., NICE guidelines, ESH/ESC guidelines) [5,6]. In addition, hypertension drug treatment is characterized by nonadherence of approximately 40%. In this challenging environment, we developed a slightly different model for patient motivation in hypertension care.

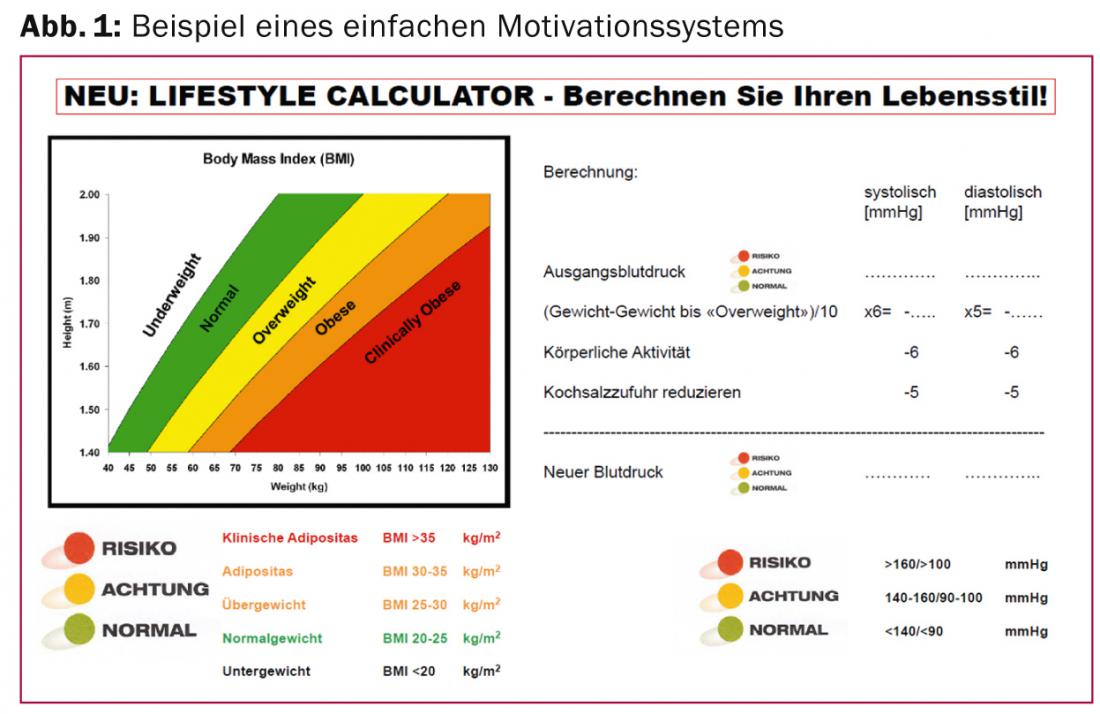

For this purpose, we measure the blood pressure and visualize the risk by the measured value in terms of a traffic light. Then we evaluate the influence of general measures together with the patient. This allows the patient to see what effect a reduction in body weight would have on their blood pressure. We also point out to the patient the limits or possibilities of weight loss. On the one hand, this information provides him with a decision-making aid for weight loss, and on the other hand, it avoids exaggerated expectations that could be detrimental to adherence [7]. A 40% endurance load for more than 90 minutes per week is associated with a simulated pressure reduction of approx. 6 mmHg, a 50% reduction in salt intake (for patients whose salt intake is above the Swiss mean of 7.2-8.1 g/d in women and 10.3-10.7 g/d in men) with a pressure reduction of 5 mmHg [8].

After taking the general measures into account, we again show the patients the optimized blood pressure with the colors of a traffic light (Fig. 1) . On the one hand, this shows patients whether their blood pressure would probably require treatment at all if the general measures were observed, and on the other hand, whether the high blood pressure should definitely be lowered with medication. This procedure then leads, comparable to the ARRIBA system, to an agreement with the patient regarding the time when drug therapy is initiated (the time limit is also required in the guidelines, but unfortunately often not consistently followed). This procedure increases the certainty for patient and physician to know the required measures or therapies or to initiate them in due time and creates a basis of understanding and trust.

All educational levels should be reached

In summary, patients, informed of the consequences of their actions, should have therapy proposed that is acceptable to them. This may mean that a patient with an appropriate cardiovascular risk makes a conscious decision to preferentially control one risk factor but opposes simultaneous control of all risk factors with concomitant polypharmacy.

The appropriate information should be presented according to the patient’s level of education, and the appropriate tools must be available for this purpose. The need to reach all educational groups is derived from the FOPH’s MOSEB report. This shows that educationally disadvantaged population groups in particular have poorer health and impaired health behavior, which is reflected, among other things, in a higher intake of medication. Here, health insurers in Switzerland should support corresponding initiatives and studies to optimize care – like the Allgemeine Ortskrankenkassen in Germany. This commitment could easily be justified by the risk reduction gained and the expenses saved on drug therapies. Insight and understanding seem to me to be the most reliable path from reparative to preventive medicine.

Literature:

- Wirtz M, Caspar F. Inter-rater agreement and inter-rater reliability. Göttingen 2002.

- Hirsch O, et al: Acceptance of shared decision making with reference to an electronic library of decision aids (arriba-lib) and its association to decision making in patients: an evaluation study. Implement Sci 2011; 6: 70.

- Krones T, et al: Absolute cardiovascular disease risk and shared decision making in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med 2008; 6: 218-227.

- Stacey D, et al: Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 1: CD001431.

- Hypertension: The Clinical Management of Primary Hypertension in Adults: Update of Clinical Guidelines 18 and 34. London 2011.

- Mancia G, et al: 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens 2013; 31: 1281-1357.

- Aucott L, et al: Effects of weight loss in overweight/obese individuals and long-term hypertension outcomes: a systematic review. Hypertension 2005; 45: 1035-1041.

- Stamm H, et al: Indicator collection for the monitoring system nutrition and physical activity. 2014.

CARDIOVASC 2015; 14(1): 24-26