About 12% of the population suffers from migraine. Neurological disease is the second most common reason for living with disability worldwide and the most common reason for people under age 50. Good prophylaxis reduces the risk of disease progression and can lead to remission of the disease. For this purpose, CGRP (receptor) antibodies and neuromodulation with Cefaly represent two important pillars.

Migraine is a neurological disorder affecting approximately 12% of the population [1]. It occurs about three times more frequently in women than in men. Migraine is the second most common reason after lower back pain for living with disability worldwide and the most common reason for people under 50 years of age [2]. People with chronic migraine lose about 14% of their annual productivity, and 20% of them report being unable to perform tasks required for their jobs [3]. Each year, this results in considerable costs for those affected, as well as for employers and the healthcare system.

The essence of the disease is that affected patients have a lifelong predisposition to migraine attacks. The pathomechanism of the attack has not been fully elucidated. The most important finding in recent years is that the headache attack itself is most likely associated with dysfunction of diencephalic and mesencephalic structures, namely the hypothalamus and the periaqueductal gray [4]. Immediately before attacks, the dysfunction of these areas leads to a processing disturbance of sensory input, especially sensitive from the areas of the trigeminal nerve, responsible for the pain, but also from other areas such as the gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting) or the visual/auditory (photophobia/phonophobia) system [5]. In addition to this central mechanism, the neuropeptide calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), has recently been shown to be highly relevant. This is elevated in the jugular venous blood during migraine attacks and falls again after successful therapy with sumatriptan [6,7]. Furthermore, infusions of CGRP can trigger headache attacks in patients with migraine, and blockade of CGRP receptors can stop migraine attacks [8,9]. The development of antibodies against the CGRP system has revolutionized migraine therapy in the last decade, and oral CGRP receptor blockers will continue to gain increasing importance in Switzerland in the coming years.

The goal of this article is to provide an overview of current and novel migraine therapy methods with an emphasis on the challenges of using them in everyday life.

Therapy

Migraine therapy consists of two main pillars: acute therapy taken as needed with the goal of relieving migraine pain, and basic therapy taken regularly with the goal of reducing the frequency and also the intensity or duration of migraine attacks.

Acute therapy: For mild attacks, NSAIDs continue to be sufficient, while for moderate to severe migraine attacks or in the absence of a response, triptans are used, which are specific migraine medications. The triptans differ from one another in terms of potency, duration of action and mode of application. Strongly effective and with rapid onset of action are, for example, subcutaneous and nasal sumatriptan, nasal zolmitriptan, and eletriptan or rizatriptan. For long-lasting attacks, preparations with a long half-life, such as naratriptan, frovatriptan, or the combination of a triptan with the long-acting NSAID naproxen are options. Almogran, naratriptan, and frovatriptan are preparations with a favorable side effect profile.

The side effects, some of which are vasoconstrictor-related, include: a temporary increase in blood pressure, rarely circulatory disturbances, ECG changes, cardiac arrhythmias, paresthesias of the extremities, a feeling of cold up to Raynaud’s syndrome, which is very rare in clinical practice, dizziness, lightheadedness or fatigue, and flushing.

It is important to avoid medication overuse headache. According to ICHD-3 classification, this is present in patients who have chronic headache, i.e., more than 15 headache days with medication use on >10 days/month for triptans or >15 days/month for analgesics.

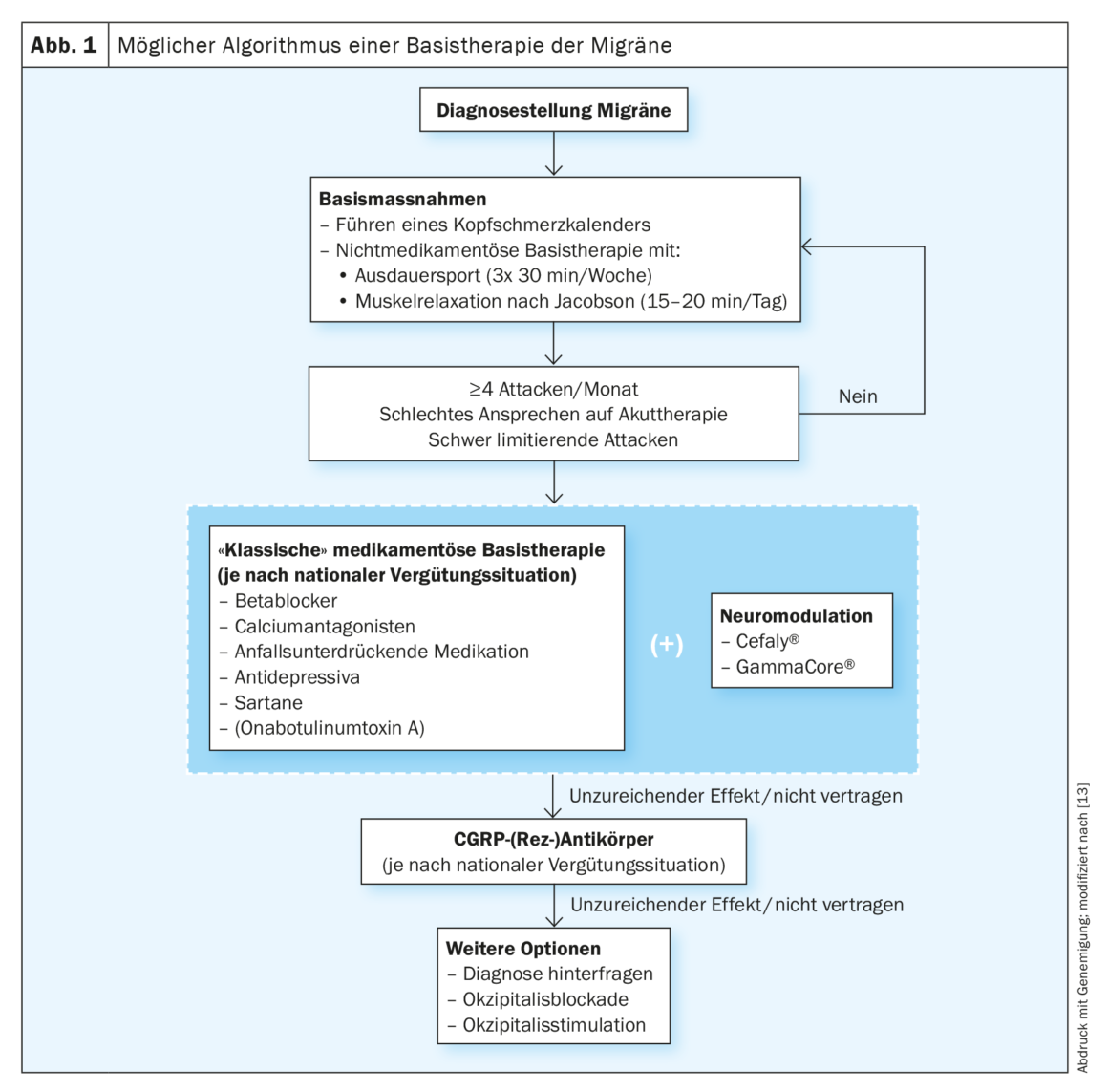

Basic therapy: Basic therapy consists of drug and non-drug measures. It is important to note that optimal baseline therapy can significantly reduce the risk of disease progression (from 6.8% to 1.9%) [10].

Non-drug measures

This is a healthy lifestyle with regular sleeping and eating times, balanced diet and regular exercise (at least 3x30min per week). In fact, new studies show that strength training is slightly more effective than endurance exercise [11]. Relaxation techniques such as Jakobson’s progressive muscle relaxation are also important and can achieve a reduction in migraine days of over 40% [12]. The instruction is simple and can be taught by physiotherapists or learned by self-study (e.g. via InselApp or on Youtube). Other nonpharmacologic measures include biofeedback, psychological pain management, and cognitive behavioral therapy, if appropriate.

Medicinal measures

The use of drug prophylaxis is decided on an individual basis depending on the patient’s level of suffering and attitude. More than four migraine attacks per month, prolonged attacks, inadequate response to acute therapy, medication overuse, frequent migraine-related absenteeism, and a previous migrainous infarction are typical indications for initiation of basic drug therapy. (Fig. 1). It is important for the choice of therapy to consider the patient’s comorbidities to prevent adverse effects. In the case of a desire to have children, beta blockers as well as amitriptyline are typically possible in consultation with the gynecologist. For the other agents such as topiramate or flunarizine, the importance of contraception should always be stressed in women of childbearing age.

The prophylactic effects of the beta-blockers propranolol and metoprolol, the calcium antagonist flunarizine, the anticonvulsants valproic acid and topiramate, and the antidepressant amitriptyline are best demonstrated by controlled studies. The antihypertensive candesartan and the SNRI venlafaxine are also good alternatives. Slow dosing and information about side effects are important.

Baseline therapy should be taken for three months and efficacy evaluated using the headache calendar. If effective for at least six months, a cautious reduction may be attempted. Onabotulinumtoxin type A is not approved in Switzerland for the treatment of migraine, but can be applied for in individual cases via a cost approval. It was shown to be more effective than placebo in the prophylaxis of chronic migraine (mean reduction in monthly headache days of 8.4 with onabotulinumtoxin type A vs. 6.6 with placebo; p<0.001) in both the Phase III PREEMPT 1 and 2 trials [14]. According to the PREEMPT regimen, the patient receives 31 injections at seven specific head and neck muscle sites with a minimum dosage of 155 units. The interval between treatments is three months.

Obstacles

A common problem with migraine patients is the patient’s “long journey” to diagnosis or treatment. Many patients first try medications from their acquaintances or preparations they find on the Internet or obtain from their pharmacist. If, in the course of the disease, the level of suffering increases, the family doctor is consulted. It can take months to years for the patient to be referred to a neurologist or a neurologist who specializes in headaches. This long journey of suffering is often also associated with anxiety, hopelessness, frustration and skepticism about medication.

Another problem is the low proportion of patients receiving basic therapy. Despite medical advice, only 26% of patients eligible for basic therapy received it in one study. Approximately two-thirds of patients with chronic migraine have never received basic therapy [15]. This is further complicated by low adherence. About 80% of patients with chronic migraine discontinue therapy in the first year [16]. Similar numbers result for patients with episodic migraine [17]. The main reasons for this are unclear, but lack of hope that the drug will work at all, concern about side effects, cost, and some skepticism among young people about oral medication taken daily are certainly relevant.

Options and recent findings

It is important that the primary point of contact for patients (pharmacists, primary care physicians) identify the more complex cases early. More severely affected patients have frequent migraine attacks or even a continuous headache; they require regular analgesics and thus have an increased risk of chronicity or respond only temporarily, if at all, to conventional analgesics or basic therapeutics.

Antibody therapy: A major advance in the treatment of migraine is the use of monoclonal antibodies, which have been approved in Switzerland for a few years. These drugs are subject to limitatio. They may be used in refractory migraine patients with high-frequency episodic (≥8 migraine days/month) or chronic migraine. Therapy refractory in this context is defined as previous treatment with at least two of the following medications that was unsuccessful or discontinued due to side effects: Beta-blockers (metoprolol or propranolol), amitriptyline, seizure suppressant medication (mainly topiramate, but also valproate), and calcium antagonists (mainly flunarizine). Alternatively, contraindications for all four groups must be present. Advantages of these substances are rapid onset of action, good efficacy and tolerability, and ease of use (1× per month, for some 1× every three months). Thus, better adherence compared to oral therapeutics is expected. The main side effects are constipation and local reaction around the injection site. Disadvantages of the therapy are certainly the rather high costs, the complex limitatio described above and of course the relatively short time the preparations are available with correspondingly little experience. For example, in recent years, outside of phase III trials, it has been found that CGRP antibodies can probably worsen Raynaud’s syndrome, sometimes significantly, and that closer monitoring may be needed in some patients with arterial hypertension or cardiopathy.

Specifically, these drugs are antibodies against the CGRP receptor (erenumab) or against the CGRP ligand itself (eptinezumab, fremanezumab, galcanezumab). Erenumab, fremanezumab and galcanezumab are administered subcutaneously, eptinezumab intravenously.

Because eptinezumab is administered intravenously, it acts particularly quickly. For example, when prophylaxis is started within an attack, 46.6% of patients are pain-free within four hours compared with 26.4% in the placebo group [18]. It should be emphasized that eptinezumab is not approved for the acute treatment of migraine. The limiting factor may be the hospital visit required for the infusion. Fremanezumab together with eptinezumab offer the advantage of single use over three months, unlike erenumab and galcanezumab, which are injected 1× month. For galcanezumab, loading should be done with dual dosing on the first application. Erenumab offers the advantage of possible dose increase (from 70 mg to 140 mg).

Neuromodulation: in neuromodulatory approaches, electrical and/or magnetic stimulation procedures act directly on neurons in the brain or peripheral nerves with the aim of increasing the pain threshold and thus reducing the frequency and intensity of pain sensation. The advantage of neuromodulation, especially the noninvasive procedures, is the lack of systemic side effects and the resulting presumed better tolerance compared with oral medications. In addition, these procedures can be used daily as acute therapy without risk of overuse headache.

A distinction is made between invasive procedures, in which a stimulator with electrodes is implanted, and non-invasive procedures, in which devices are inserted on the skin by the patient. Among noninvasive procedures, this article discusses transdermal stimulation of the vagus nerve and supraorbital nerve. Invasive procedures such as nerve occipital stimulation should be reserved for therapy-resistant cases and used only after interdisciplinary evaluation by neurologists with neurosurgeons and psychosomatic colleagues.

Transcutaneous stimulation of the supraorbital nerve (Cefaly®)

After attaching a self-adhesive electrode to the forehead, Cefaly is magnetically connected to the electrode. Precise micro-pulses are then sent through the electrode to the supraorbital and supratrochlear branches of the ophthalmic nerve to either relieve the headache during a migraine attack (acute treatment) or to prevent future migraine attacks (preventive treatment).

The device offers two different programs: One program for basic therapy, which is applied daily for about 20 minutes (low-frequency stimulation) and a second program for acute therapy over 60 minutes (high-frequency stimulation). Numerous studies support the effect of Cefaly in migraine. For example, a sham-controlled double-blind study showed a 19% reduction in migraine attacks in the verum group compared with 3% reduction in the placebo group [19]. In an American open pilot study, there was a 57.1% reduction in mean pain intensity after using the device for one hour [20].

In Switzerland, the device is initially purchased by patients directly from the manufacturer. If the patient does not benefit, they can return it for a partial refund. If effective, partial reimbursement is possible as a TENS unit by prescription.

Transcutaneous stimulation of the vagus nerve (GammaCore®)

Vagus nerve stimulation has long been used as adjuvant therapy for difficult-to-treat epilepsy and depression. It has already been shown that in chronic pain the vagus nerve is often less active and thus the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system is disturbed. If the parasympathetic nervous system can be stimulated, patients feel less pain.

Some studies showed an effect in cluster headache [21]. In addition, vagus nerve stimulation has been shown to inhibit cortical spreading depression, which may underlie migraine aura [22]. Open studies suggest an effect also for the treatment of acute migraine attacks [23,24]. However, two large, placebo-controlled, double-blind studies showed only a small, nonsignificant reduction in migraine days compared with Sham stimulation [25,26].

Vagus nerve stimulation with gammaCore® is usually performed 2× per day (recommended: morning and evening with 2-3 stimulations each). These last 90 sec. each. The device can be used for a maximum of 31 calendar days from the first activation and allows up to 300 stimulations. Thus, beyond the regular prophylaxis (approx. 186 stimulations), there is sufficient capacity for (acute therapeutic) reserve stimulations.

At the moment, the device is not available in Switzerland, and the current study situation is not convincing so far. For individual cases, however, it can be ordered as an individual healing trial from the UK, for example. Contraindications for the Cefaly device and the Gamma-Core are implanted electronic devices such as pacemakers.

Prevention in everyday life

CGRP monoclonal antibodies may help address unmet needs in migraine prevention in everyday life. Real-world evidence data show a comparable efficacy and safety profile compared to randomized pivotal trials. Data from the Garlit study are worth mentioning [27]. This is a multicenter, prospective observational cohort study from Italy with 163 participants with high-frequency episodic migraine (HFEM, 8-14 migraine days per month) and chronic migraine (CM). Patients received a loading dose of galcanezumab 240 mg s/c followed by 120 mg s/c monthly.

After six months, monthly migraine days decreased by eight days in HFEM patients and migraine headache days decreased by 13 days in CM patients. In addition, there was a rapid reduction in migraine days already in the first month of treatment in over 60% of patients, which persisted over the six months. 76.5% of HFEM and 63.5% of CM patients achieved a 50% response rate over three consecutive months. In addition, a favorable tolerability profile was seen with 10.3% adverse events over six months, most commonly constipation and injection site reactions. No serious adverse events were reported.

In a real-world study of 26 patients with chronic migraine with and without medication-overuse headache who had failed at least three preventive therapies, 62% of patients showed a switch from chronic to episodic migraine in the first year of treatment [28]. In contrast, the probability of spontaneous remission is only 26.1% over two years. The above data refer to galcanezumab, but experience from clinical practice yields comparable results for all antibody preparations.

Summary

Currently, there are a large number of effective therapies for the treatment of migraine. A distinction is made between acute therapy and basic therapy, and between drug and non-drug procedures. Good prophylaxis reduces the risk of disease progression and can lead to remission of the disease. Unfortunately, only a small proportion of migraine patients receive basic therapy, although this would be indicated. And patients receiving prophylaxis often show low medication adherence. Improving this is a shared responsibility of all professional groups involved in the care of migraine patients. Although approved in Switzerland only a few years ago, CGRP (receptor) antibodies already represent an important pillar of migraine therapy. A promising addition to regular non-drug prophylaxis is neuromodulation with Cefaly®.

Take-Home Messages

- Migraine is one of the most common causes of disability in people under 50.

- Good prophylaxis reduces the risk of disease progression and can lead to remission of the disease.

- CGRP (receptor) antibodies and neuromodulation with Cefaly represent two important pillars of migraine therapy.

Literature:

- Burch RC, Buse DC, Lipton RB: Migraine: Epidemiology, Burden, and Comorbidity. Neurol Clin 2019 Nov; 37(4): 631-649. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2019.06.001. Epub 2019 Aug 27. PMID: 31563224.

- Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Vos T, et al: (2018). Migraine is the first cause of disability in those under 50: will health politicians now take notice?. The journal of headache and pain, 19(1), 17. doi:10.1186/s10194-018-0846-2.

- Migraine and Disability, Headache and Migraine Policy Forum, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/

5886319ba5790a66cf05d235/t/5c65958215fcc0538b9c85en/1550161282886/HMPF_Migraine+%26+Disability+Graphic_Feb+2019 .pdf. - Maniyar FH, Sprenger T, Monteith T, et al: Brain activations in the premonitory phase of nitroglycerin-triggered migraine attacks. Brain 2014 Jan; 137(Pt 1): 232-241. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt320. Epub 2013 Nov 25. PMID: 24277718.

- Goadsby PJ, Holland PR, Martins-Oliveira M, et al: Pathophysiology of Migraine: A Disorder of Sensory Processing. Physiol Rev 2017 Apr; 97(2): 553-622. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2015. PMID: 28179394; PMCID: PMC5539409.

- Goadsby PJ, Edvinsson L, Ekman R. Vasoactive peptide release in the extracerebral circulation of humans during migraine headache. Ann Neurol. 1990 Aug;28(2):183-7. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280213. PMID: 1699472.

- Goadsby PJ, Edvinsson L: The trigeminovascular system and migraine: studies characterizing cerebrovascular and neuropeptide changes seen in humans and cats. Ann Neurol 1993 Jan; 33(1): 48-56. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330109. PMID: 8388188.

- Lassen LH, Haderslev PA, Jacobsen VB, et al: CGRP may play a causative role in migraine. Cephalalgia 2002 Feb; 22(1): 54-61. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00310.x. PMID: 11993614.

- Olesen J, Diener HC, Husstedt IW, et al, BIBN 4096 BS Clinical Proof of Concept Study Group: calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist BIBN 4096 BS for the acute treatment of migraine. N Engl J Med. 2004 Mar 11;350(11): 1104-1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030505. PMID: 15014183.

- Lipton RB, Fanning KM, Serrano D, et al: Ineffective acute treatment of episodic migraine is associated with new-onset chronic migraine. Neurology 2015 Feb 17; 84(7): 688-695. doi: 10.1212/WNL.00000000001256. epub 2015 Jan 21. PMID: 25609757; PMCID: PMC4336107.

- Woldeamanuel YW, Oliveira ABD: What is the efficacy of aerobic exercise versus strength training in the treatment of migraine? A systematic review and network meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Headache Pain 23, 134 (2022).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-022-01503-y - Meyer B, Keller A, Wöhlbier HG, et al: Progressive muscle relaxation reduces migraine frequency and normalizes amplitudes of contingent negative variation (CNV). J Headache Pain 17, 37 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0630-0

- Frank J, Schankin CJ: Current and future treatment options for migraine: an update. Neuro Current 2021;5: 23-30. (The image reproduced with permission).

- Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, PREEMPT Chronic Migraine Study Group, et al: OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phases of the PREEMPT clinical program. Headache 2010 Jun; 50(6): 921-936.

doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01678.x. Epub 2010 May 7. PMID: 20487038. - Lipton RB, Nicholson RA, Reed ML, et al: Diagnosis, consultation, treatment, and impact of migraine in the US: results of the OVERCOME (US) study. Headache 2022 Feb; 62(2): 122-140. doi: 10.1111/head.14259. epub 2022 Jan 25. PMID: 35076091; PMCID: PMC9305407.

- Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, et al: Adherence to oral migraine-preventive medications among patients with chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2015 May; 35(6): 478-488. doi: 10.1177/0333102414547138. epub 2014 Aug 27. PMID: 25164920.

- Berger A, Bloudek LM, Varon SF, Oster G: Adherence with migraine prophylaxis in clinical practice. Pain Pract 2012 Sep;12(7): 541-549. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00530.x. Epub 2012 Feb 2. PMID: 22300068.

- Winner, et al: Effects of Intravenous Eptinezumab vs Placebo on Headache Pain and Most Bothersome Symptom When Initiated During a Migraine Attack: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021; 325(23): 2348-2356.

- Schoenen J, Vandersmissen B, Jeangette S, et al: Migraine prevention with a supraorbital transcutaneous stimulator. A randomized controlled trial. Neurology Feb 2013, 80(8); 697-704;

DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182825055 - Chou DE, Gross GJ, Casadei CH, Yugrakh MS: External Trigeminal Nerve Stimulation for the Acute Treatment of Migraine: Open-Label Trial on Safety and Efficacy. Neuromodulation 2017 Oct; 20(7): 678-683. doi: 10.1111/ner.12623. Epub 2017 Jun 5. PMID: 28580703.

- Gaul C, Diener HC, Silver N, Magis D, et al: Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation for PREVention and Acute treatment of chronic cluster headache (PREVA): A randomised controlled trial. Cephalalgia. 2016 May;36(6):534-46. doi: 10.1177/0333102415607070. epub 2015 Sep 21. PMID: 26391457; PMCID: PMC4853813.

- Chen SP, Ay I, de Morais AL, et al: Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits cortical spreading depression. Pain 2016; 157: 797-805

- Barbanti P, Grazzi L, Egeo G, et al: Noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation for acute treatment of high-frequency and chronic migraine: an open-label study. The journal of headache and pain 2015; 16: 61. 11.

- Goadsby PJ, Grosberg BM, Mauskop A, et al: Effect of noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation on acute migraine: an openlabel pilot study. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache 2014; 34: 986-999.

- Diener HC, Goadsby PJ, Ashina M, et al: Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) for the preventive treatment of episodic migraine: The multicentre, double-blind, randomised, sham-controlled PREMIUM trial. Cephalalgia 2019 Oct; 39(12): 1475-1487. doi: 10.1177/0333102419876920. epub 2019 Sep 15. PMID: 31522546; PMCID: PMC6791025.

- Silberstein SD, Calhoun AH, Lipton RB, EVENT Study Group, et al: Chronic migraine headache prevention with noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation: the EVENT study. Neurology 2016 Aug 2; 87(5): 529-38. doi: 10.1212/WNL.00000000002918. epub 2016 Jul 13. PMID: 27412146; PMCID: PMC4970666.

- Vernieri F, Altamura C, Brunelli N, et al: Galcanezumab for the prevention of high frequency episodic and chronic migraine in real life in Italy: a multicenter prospective cohort study (the GARLIT study). J Headache Pain 2021 May 3;22(1): 35. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01247-1. PMID: 33941080; PMCID: PMC8091153.

- Vaghi G, Bitetto V, De Icco R, et al: Real life experience of one year treatment with galcanezumab in chronic migraine with and without medication overuse headache. Cephalalgia 2021; 41: 162.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2023; 21(2): 6-10.