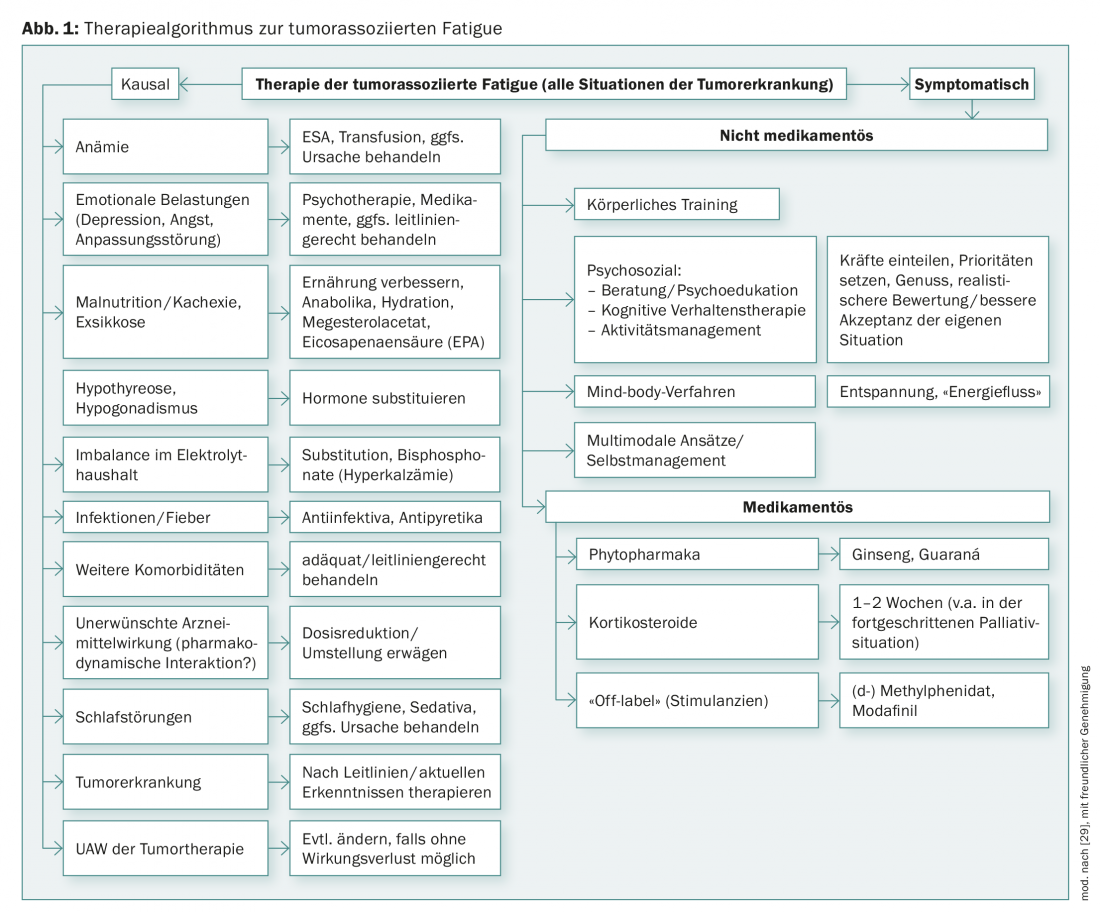

An important intervention for tumor-associated fatigue is to inform patients that fatigue is common and that the symptoms, although unpleasant, are usually at least not dangerous. If in the course of the diagnosis (co)causes for the fatigue can be identified (e.g. anemia, depression or certain medications), causal therapy should be given if possible. Drug and non-drug interventions with evidence from randomized trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses are available for symptomatic therapy. Examples include exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, herbal medications, pychostimulants, and corticosteroids. Therapy should be adapted to the patient’s possibilities in the sense of participatory decision-making and should ideally be multimodal, taking into account possible contraindications.

Tumor fatigue is accompanied by a distressing feeling of unusual, severe fatigue and exhaustion. Depending on its course, duration and severity, it can lead to anything from temporary indisposition to inadequate coping with everyday life to permanent disability. In addition, tumor fatigue is associated with shorter survival times. Despite these sometimes severe effects, it is often not perceived as requiring treatment or as being treatable – even though evidence-based treatment options exist. Depending on the result of the (differential) diagnosis, the therapy of cancer-related fatigue (CrF) is causal and/or symptom-oriented [1]. Causal and symptomatic therapies can be combined, taking into account possible contraindications and drug interactions. In most cases, multimodal treatment is necessary [2]. Each treatment plan should be individualized to the patient and therapy should begin early to counteract possible chronicity [3,4].

Inform patients about tumor fatigue

The first essential intervention is to provide in-depth information about CrF to those affected. Many patients do not know that tumor-associated fatigue exists and they do not understand why they are so exhausted – especially when they are considered cured. Fears arise: “Is the cancer perhaps progressing (unnoticed) after all? Is the (increasing) fatigue an indication that I will soon fall asleep forever?” Furthermore, the “invisibility” of the phenomenon leads contact persons to trivialize the fatigue, which is experienced as frustrating by the patients [5]. Just knowing that the discomfort has a name and that there are ways to treat it can be very relieving. If the information is provided preventively, e.g. before the start of tumor therapy, fears can be prevented [4,5]. It is helpful to refer patients to brochures and information from the Swiss Cancer League. Interventions can be causal or symptom-based (Fig. 1).

Causal therapy

The causal therapy of possible (co-)causes or accompanying factors of tumor-associated fatigue (Fig. 1) has priority over symptomatic treatment. Even if it is not always possible to eliminate all the underlying diseases or dysfunctions identified as possible causes, even partial success can help to reduce fatigue and give patients the feeling that they are not left alone with their worries and needs.

If – in individual cases – anemia is found to be the cause of tumor fatigue, blood transfusions or hematopoietic growth factors (erythropoiesis stimulating agents, ESA) may help. The use of ESA may increase the risk of thromboembolic events and shorten progression-free and overall survival. Therefore, in line with the recommendations of the current guidelines, they should only be used at Hb <10 g/dL, during myelosuppressive chemotherapy, and in non-curative objectives [6,7].

If a differential diagnosis of unipolar depression has been made, this should also be treated in accordance with the guidelines [8]. It may also improve fatigue. However, clinical experience shows that tumor patients – obviously without thorough diagnostics – are very often prescribed antidepressants although they claim not to be depressed but only tired and exhausted. The prescription of antidepressants is understandable from a medical point of view, since fatigue and exhaustion are core symptoms of depressive diseases and tumor patients are often depressed, but it is not effective if there is no underlying depression. None of the randomized, placebo-controlled trials conducted to date have demonstrated that antidepressants improve tumor-associated fatigue. Also, patients with fatigue who have received antidepressants (e.g., mirtazapine or venlafaxine) report that they do not feel better as a result [9].

Principles of symptomatic therapy

If it is not possible to attribute tumor-associated fatigue to specific, treatable causes, symptom-based therapies should be offered. Provided there is nothing to the contrary from a medical point of view, symptom-oriented therapies can also be combined.

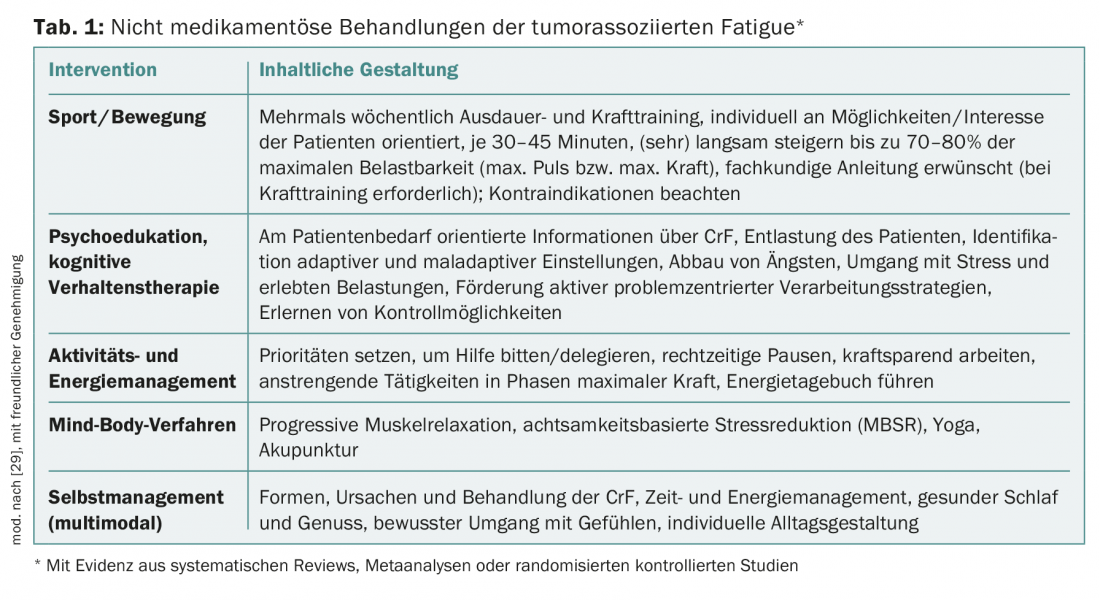

The following suggestions for drug and non-drug symptomatic treatments of CrF come from randomized controlled trials, their summaries in reviews, or from meta-analyses (corresponding to an evidence level 1-2). Important non-medicinal treatment options are physical exercise and psychoeducation (tab. 1) . Recently, a randomized study also demonstrated the effect for a German-language self-management program [10,11].

Physical activity/sports

Physical activity of any kind is a very intensively studied intervention for the treatment of CrF. It has been shown time and again that CrF can be improved by moderate physical activity. According to a recent meta-analysis [12], this applies to patients both during and after tumor treatment. It is important that the patient does not overexert himself and that the physical exercise is enjoyable. For the implementation of physical training in patients with CrF, the reader is referred to the work of Dimeo [13]. The brochure “Fitness trotz Fatigue” (with concrete exercise instructions and DVD) of the German Fatigue Society, which can also be ordered free of charge by patients, has proven itself in everyday life.

Psychosocial interventions

All of the psychosocial interventions listed in Table 1 can effectively mitigate CrF. Psychoeducation and counseling are mainly intended to help patients understand CrF [3]. This includes informing patients about possible causes and therapeutic options.

Cognitive behavioral therapies assume that emotions arise primarily from the subjective evaluation of concrete situations. Evaluations appropriate to reality (= rational) lead to adequate feelings, evaluations inappropriate to reality (= irrational, catastrophizing) lead to emotional problems. Cognitive behavioral therapies aim to work with the patient to identify and challenge dysfunctional evaluations/attitudes and adjust them to reality. Cognitive restructuring makes it easier for patients to cope better with their situation. Guidance on activity and energy management can be integrated into everyday practice.

Mind-Body Process

Yoga has been shown to be effective in a study of breast cancer patients [14]. The authors of a meta-analysis that did not yet include this study estimate the overall effect of yoga on CrF to be rather weak [15]. For acupuncture, the data situation is assessed as unclear in two systematic reviews [16,17].

Self-Management

A six-module self-management program developed in Germany for patients with CrF has been shown to be effective in a randomized trial [11]. The group of authors has published a manual for this purpose, which makes it possible to offer the program as group training [10]. In addition, a patient guide was also created [18].

Pharmacological therapies

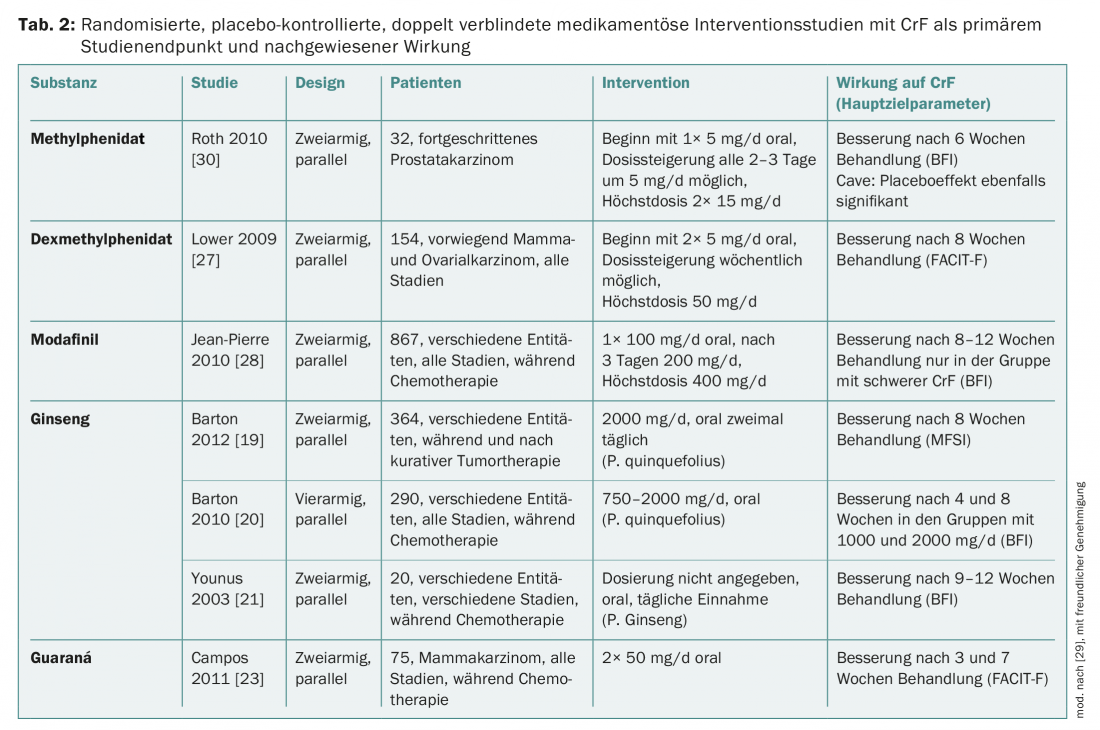

Evidence from randomized, placebo-controlled trials is also available for the pharmacological treatment of CrF, namely for phytopharmaceuticals, psychostimulants, and corticosteroids (Table 2) . For phytopharmaceuticals and psychostimulants, there is also evidence from systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses.

Ginseng is traditionally considered a remedy for all kinds of exhaustion. In the context of CrF, American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) and Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) have been studied [19–21]. All studies have shown that ginseng (when well tolerated) can improve CrF. Panax ginseng is approved as an over-the-counter drug. Details on ginseng can be found in the Complementary Therapy Guideline [22].

Guaraná (Paullinia cupana) is a plant native to Brazil, traditionally used to increase physical and mental performance. The main active ingredient is caffeine. In one of three studies of efficacy on CrF, guarana was shown to improve CrF in breast cancer patients during chemotherapy [23]. This is confirmed by a meta-analysis with a total of 137 patients.

Corticosteroids may have a CrF-reducing effect in palliative care settings. Therefore, the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC), among others, recommends considering corticosteroids if, for example, a patient is to be given a pleasant Christmas [24]. Specifically for dexamethasone, CrF was shown to be ameliorated in a placebo-controlled study [25]. Because corticosteroids can induce myopathy with prolonged use and thereby worsen CrF, they are unsuitable as long-term therapy in patients with post-cancer fatigue. In the advanced palliative situation, CrF can be protective for the patient, so therapy should not be given in every case.

(Dex-)methylphenidate (MPH): The study situation for MPH is still contradictory, but there are indications that especially patients with advanced tumor disease who have already suffered from pronounced CrF for a longer period of time may benefit from MPH. That MPH can impressively help individual patients was also confirmed in a study of the German Fatigue Society with retarded MPH [26]. Fatigue can also be reduced with d-MPH [27]. Side effects include dizziness, headache, blood pressure elevation, and dry mouth. At the dosages currently recommended, these side effects occur rather rarely. According to clinical experience, one can start with a dosage of 10 mg daily and increase it after a few days in case of non-response. If there is still no improvement within a few days, the therapy attempt is terminated. In Switzerland, the use of MPH and D-MPH can only be off-label.

Modafinil is most effective in severe CrF [28]. Because of the occurrence of severe psychiatric symptoms and cutaneous reactions, the European Medicine Agency (EMA) has limited the use of modafinil to the treatment of adults with excessive sleepiness [29].

For the Working Group on Supportive Measures in Oncology, Rehabilitation and Social Medicine of the German Cancer Society (ASORS). www.asors.de

Second reprint courtesy of Springer Medizin. Published in: In Focus Oncology 2013; 16(9): 2-6.

Literature:

- Fischer I: Diagnostics and differential diagnosis of tumor fatigue. InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(3): 20-24.

- Heim ME, Feyer P: The tumor-associated fatigue syndrome. Journal Oncology 2011; 01: 42-47.

- Weis J: Cancer-related fatigue: prevalence, assessment and treatment strategies. Expert Rev Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res 2011; 11(4): 441-446.

- Kuhnt S, et al: Predictors of tumor-associated fatigue: longitudinal analysis. Psychotherapist 2011; 56: 216-223.

- Glaus A, et al: What cancer patients think of information on fatigue: an assessment by patients in Switzerland and England. Nursing 2002; 15(5): 187-194.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Cancer- and Chemotherapy-Induced Anemia, Version 1.2014.

- Rizzo JD, et al: American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Society of Hematology Clinical Practice Guideline Update on the Use of Epoetin and Darbepoetin in Adult Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(33): 4996-5010.

- S3 Guideline/National Health Care Guideline Unipolar Depression. www.versorgungsleitlinien.de/themen/depression/pdf/s3_nvl_depression_lang.pdf.

- Fischer I, Rüffer JU: Tumor-associated fatigue or depression? neuro aktuell, Westermayer Verlag.

- de Vries U, et al: Fatigue individuell bewältigen (FIBS): Schulungsmanual und Selbstmanagementprogramm für Menschen mit Krebs. Bern: Hans Huber, Hogrefe 2011.

- Reif K, et al: A patient education program is effective in reducing cancer-related fatigue: A multi-centre randomised two-group waiting-list controlled intervention trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2013; 17(2): 204-213.

- Puetz TW, Herring MP: Differential effects of exercise on cancer-related fatigue during and following treatment: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med 2012; 43(2): e1-24.

- Dimeo FS: Physical activity and sport in tumor diseases: Exercise at its own pace. In Focus Oncology 2010; 13(5): 60-66.

- Bower JE, et al: Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2012; 118(15): 3766-3775.

- Boehm K, et al: Effects of yoga interventions on fatigue: a meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012; 124703.

- He X, et al: Acupuncture and Moxibustion for Cancer-related Fatigue: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2013; 14(5): 3067-3074.

- Posadzki P, et al: Acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Support Care Cancer 2013; 21(7): 2067-2073.

- Reif K, et al: Ways out of exhaustion: guide to tumor-related fatigue. 1st ed. Bern: Hans Huber; 2011.

- Barton DL, et al: Ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) to Improve Cancer-Related Fatigue: A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013; 105(16): 1230-1238.

- Barton DL, et al: Pilot study of Panax quinquefolius (American ginseng) to improve cancer-related fatigue: a randomized, double-blind, dose-finding evaluation: NCCTG trial N03CA. Support Care Cancer 2010; 18(2): 179-187.

- Younus J, et al: A double blind placebo controlled pilot study to evaluate the effect of ginseng on fatigue and quality of life in adult chemo-naïve cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2003; 22(4): 733.

- Horneber M, Fischer I: Guideline Complementary Therapy: Ginseng. www.dghoonkopedia.de/de/onkopedia/leitlinien/komplementaere-therapie/komplementa-retherapie.pdf.

- Campos O, et al: Guarana (Paullinia cupana) Improves Fatigue in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Systemic Chemotherapy. J Altern Complement Med 2011; 17(6): 505-512.

- Radbruch L, et al: Fatigue in palliative care patients – an EAPC approach. Palliat Med 2008; 22(1): 13-32.

- Yennurajalingam S, et al: Dexamethasone (DM) for cancer-related fatigue: A double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(suppl): abs 9002.

- Heim ME, et al: Randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study of modified methylphenidate on cancer-related fatigue (CRF). J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2012; 138(Suppl. 1): 13-Abs B25-0058.

- Lower EE, et al: Efficacy of Dexmethylphenidate for the Treatment of Fatigue After Cancer Chemotherapy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009; 38(5): 650-662.

- Jean-Pierre P, et al: A phase 3 randomized, placebocontrolled, double-blind, clinical trial of the effect of modafinil on cancerrelated fatigue among 631 patients receiving chemotherapy. Cancer 2010; 116(14): 3513-3520.

- Horneber M, et al: Tumor-associated fatigue: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2012; 109(9): 161-171.

- Roth AJ, et al: Methylphenidate for fatigue in ambulatory men with prostate cancer. Cancer 2010; 116(21): 5102-5110.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(4): 21-25.