Several meta-analyses demonstrate the high effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy, the Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System for Psychotherapy (CBASP), acceptance and commitment therapy, psychodynamic brief psychotherapy, long-term psychoanalytic therapy, and interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of depression. Therapies of the future could include virtual reality and new digital psychotherapy approaches, in addition to further development of the methods presented.

Approximately one fifth of all people develop depression in the course of their lives. Treatment begins with an educational talk about the highly successful treatment options with the goal of providing hope and relieving patients. The goal of further treatment is remission, i.e. complete recovery, for which a sustainable therapeutic relationship must exist during the course. Psychotherapeutic treatments specifically designed to treat depression are equally effective as antidepressants and are recommended in the guidelines for all degrees of depression, regardless of severity.

Prerequisites of therapy

In addition to procedure-specific effective factors, an accepting, open, actively listening and compassionate relationship contributes to the success of treatment. In addition to the relationship, psychotherapeutic procedures generally resort to motivational clarification, resource activation, problem actualization, and problem solving. Furthermore, the patient’s subjective attitude towards the disease and treatment expectations play a role. The therapist influences treatment outcome through his or her personality, values, and views on how depressive disorders arise and can be treated.

Specific psychotherapeutic approaches and their foundations are briefly illustrated below. All have shown higher efficacy and effectiveness than general supportive psychotherapy in all meta-analyses.

CBASP

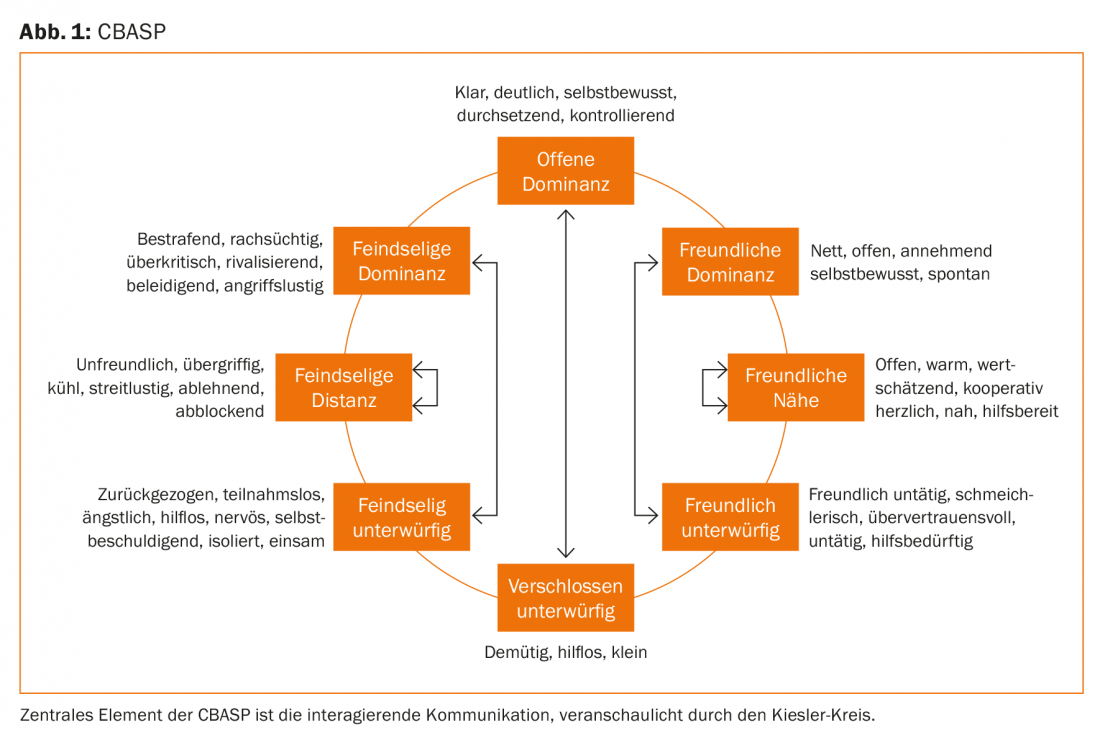

The Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System for Psychotherapy (CBASP) is specifically designed to treat chronic depression and combines cognitive, behavioral, interpersonal, and psychodynamic strategies. It can be done on an outpatient basis in an individual setting or on an inpatient basis in a group setting, although group therapy is significantly more effective and “higher dose” because more interactive learning experiences can be made and a supportive atmosphere also helps within the group. CBASP targets relational experiences. Within CBASP, empathy, problem-solving skills, and healing relational experiences are experienced. At the beginning, a list of formative reference persons is drawn up. In the context of their behavior, transference hypotheses are developed and interpersonal discrimination exercises are conducted. If, for example, “the father was always absent”, this unconscious transference will also relate to the choice of partner and here disappointments (“affinity for disinterested men”) are possibly pre-programmed, which then develop into self-deprecation and auto-aggression. Using the Kiesler circle (Fig. 1), it is worked out that an attitude in conversation leads to a complementary attitude of the counterpart and thus also to a result (see arrows in the figure). Ideally, the group will try to rethink and revise alternative attitudes and communicative strategies and thus be more likely to achieve what one wants or needs in contact with others. Expectations such as “others will laugh at me” are questioned and can ideally be falsified in the group situation. It can be experienced that a different behavior triggers different reactions. In empathy training, situations are “frozen” and reflected back by a third person and then reflected on together. CBASP success rates are very good (approximately 81% response, 44% remission); only 18% of those treated show relapse within one year.

KVT

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) of depressive disorders is based on reinforcer loss theory and learned helplessness theory. Learned helplessness means that regardless of how one behaves, negative developments cannot be influenced by one’s behavior. In the sense of a self-fulfilling prophecy, this leads to a vicious circle and recurring negative experiences. A lack of positive reinforcement and active shaping is a depression-promoting behavior pattern that is a central factor in the development and maintenance of a depressive disorder. In the course of therapy, such strategies are relearned. Activity building is accordingly a central element of CT.

ACT

As cognitive behavioral therapy evolved, the methods of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy were developed. Classical behavior therapy involves changing how symptoms occur and are dealt with, so it tends to be symptom-oriented; ACT, on the other hand, is less about addressing symptoms and more about learning psychological flexibility, i.e., creating “alternative facts.” A patient once pointedly compared the different procedures (ACT and KVT) practiced in two psychotherapeutic departments of adult psychiatry at UPK as follows: “With KVT you push the symptoms away, with ACT you bring them out again and live with them”.

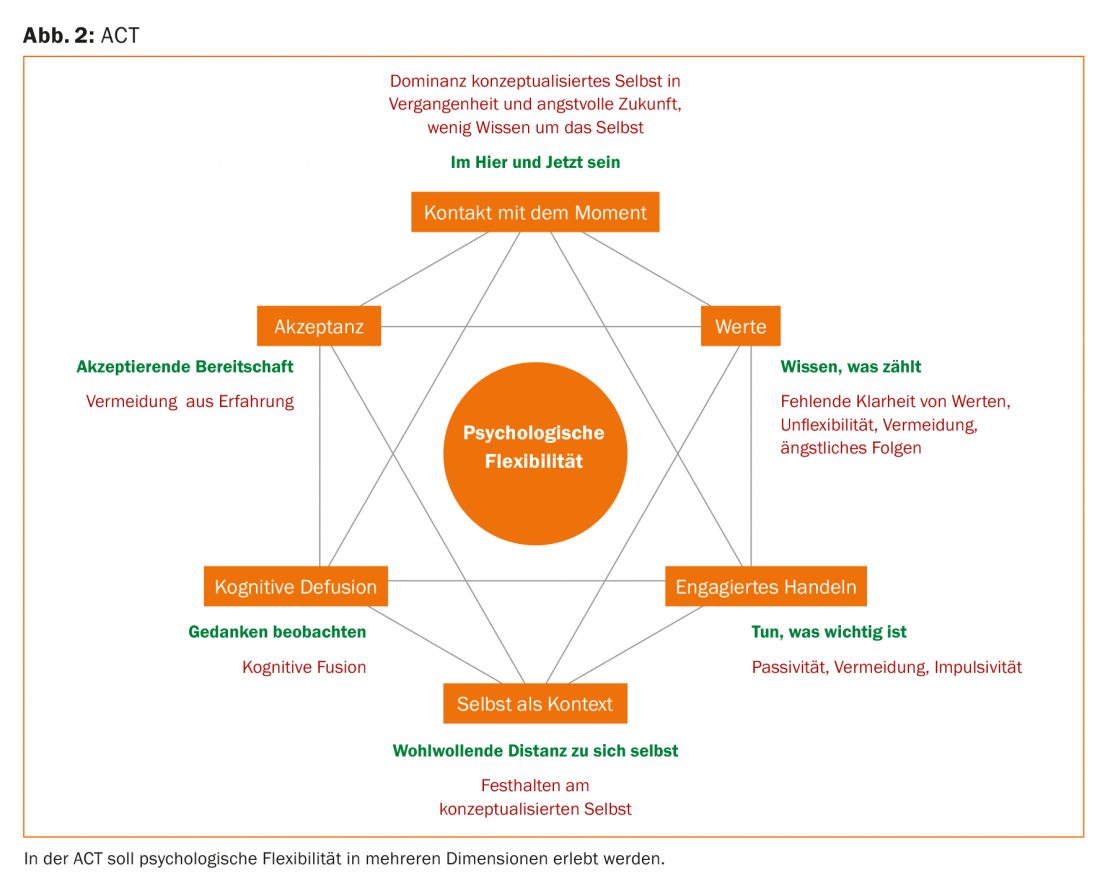

The goal of ACT is to change the relationship between experiencing symptoms and unwanted thoughts or feelings so that symptoms no longer need to be avoided. This is also easier for the person concerned. It is not to be underestimated how difficult it is to fill the time spent with symptoms (example gambling addiction, compulsions) in a meaningful way. Thus, ACT does not treat symptoms, but teaches skills to better cope with symptoms. This involves working on one’s own behavioral flexibility and promoting value-oriented action in everyday life (Fig. 2) . Psychological flexibility is developed using six core principles: Cognitive Defusion (thoughts are separated from their meaning), Acceptance (attention is focused on symptoms and space is given to them instead of fighting them), Mindfulness (situations are to be perceived with five senses and not “missed”), Self as Context (change of perspective using the example of a chessboard), Personal Values (what one wants to stand for in life is worked out, what one does not want to have missed in retrospect of life), and Committed Action (goals and values are broken down into concrete sub-steps).

Psychoanalytic-psychodynamic approaches

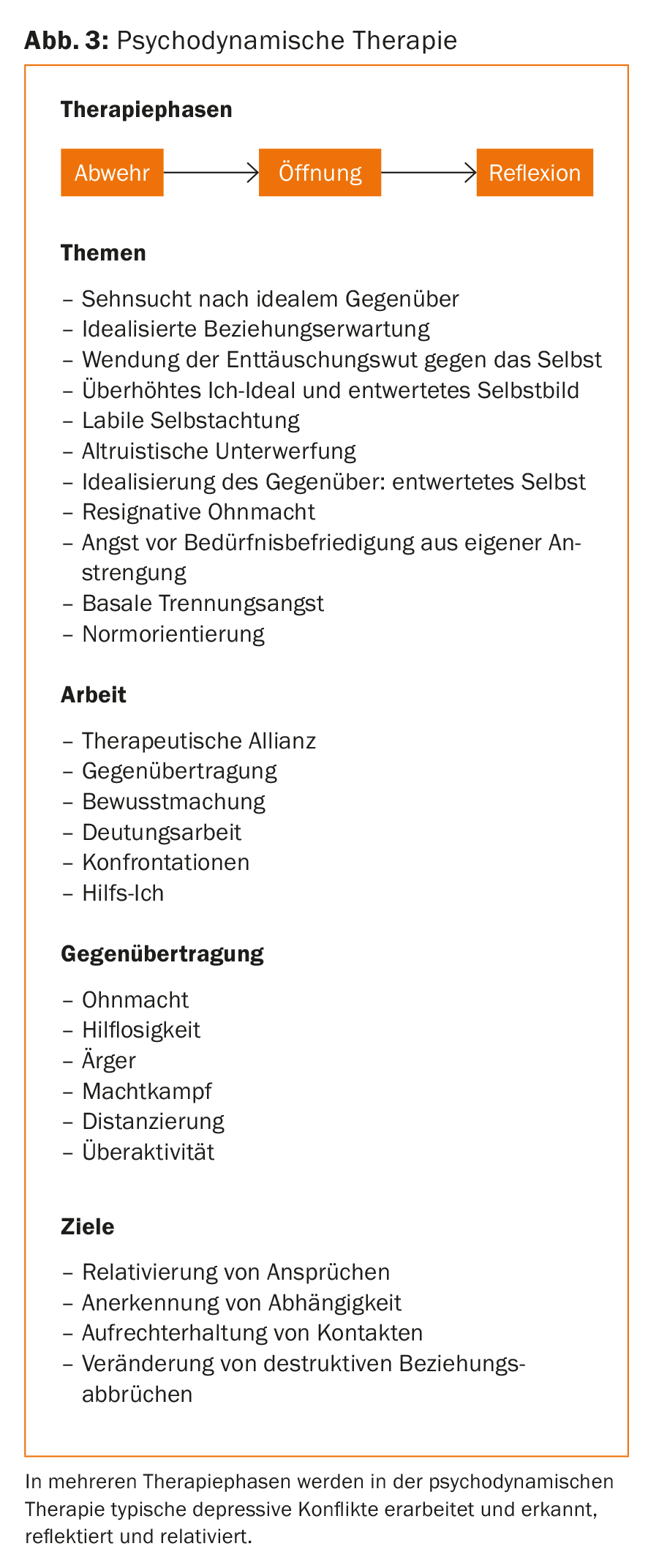

From a psychoanalytic-psychodynamic point of view, depressions are triggered by experiences of loss or mortification, which cannot be adequately processed because of a conflictual inner situation. The background is often an insecure attachment experience as a result of childhood traumas and stresses, accompanied by excessive dependence on other people or fear of closeness. Figure 3 shows the course, the depressive conflicts and the methods of therapy as well as goals. A variety of depressive symptoms and relationship problems can be understood against this background. For example, in order to secure the relationship with important attachment figures, the tensions and feelings of anger that arise after loss and mortification are not seen as a consequence but as causal for the loss that has occurred, and are turned against one’s own ego. Patients have the feeling that it is “their own fault”.

In front of this understanding of the illness, reflective processing within a regression-promoting setting takes place in the analytic psychotherapy of depressed patients. Free speech should be promoted. Therapeutic empathy with inner experience, feelings and fears and their verbalization are important. Furthermore, the thematization of unacceptable feelings for the patients is aimed at. In this way, the conflicts that have become unconscious can be brought back to life in the here and now of the therapist-patient relationship and thus made understandable and workable. Two quality-controlled meta-analyses of the effectiveness of brief psychodynamic psychotherapies are available. Outpatient focal, short-term, psychodynamic psychotherapies are comparable to other effective depression therapies for mild to moderate depression in terms of reducing depressive symptoms.

The efficacy of long-term psychoanalytic therapy is shown in a randomized clinical trial to be somewhat delayed in initial symptom reduction compared with short-term psychodynamic therapy, but superior at 3- to 5-year follow-up.

IPT

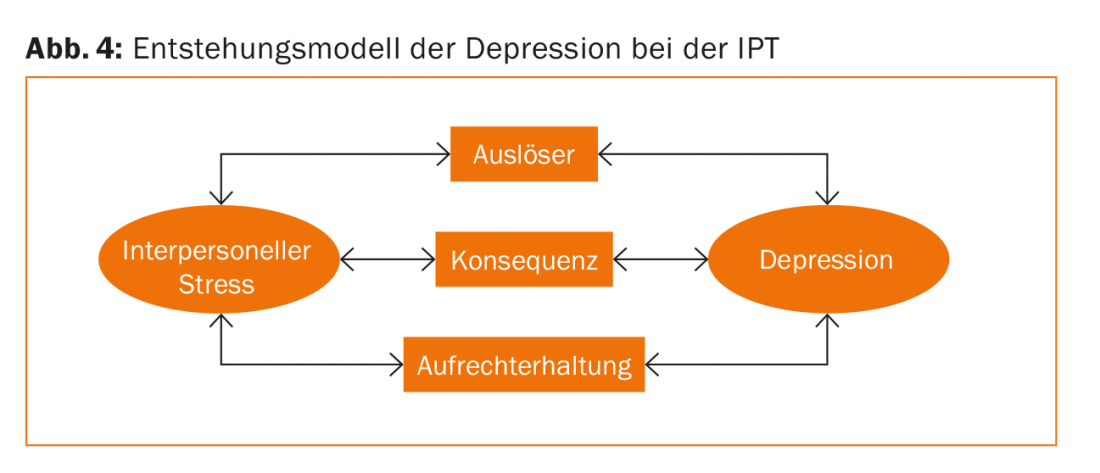

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) is a short-term therapy method specifically developed for depressive disorders, with 12-20 weekly individual sessions, pragmatically drawing on proven therapeutic concepts from behavior therapy and psychodynamic therapy (Fig. 4).

An important goal of therapy is to address distressing interpersonal and psychosocial stressors such as unresolved grief, partner conflict, role reversal, role conflict, social isolation, and family, work, or social conflict and communication problems-regardless of whether these stressors contribute to or are the result of the depressive disorder. A special modification of the program for the treatment of work-stress-related depressive disorders, which are becoming increasingly significant, is currently being developed as part of a research project at UPK. Learning to recognize feelings, perceive conflicts in their context, analyze role and changed role behavior after and during depression, evaluate and expand relationships and social networks, and practice new ways of coping and behaving. Self-reproach should be reduced. Often it helps to clarify the different expectations of the patient and his partner (friend) in the relationship. The patient’s wishes should be questioned and strategies developed to achieve them; ending a relationship can also be a constructive solution here. Role changes, be it marriage or divorce, employment or dismissal, a physical illness and its treatment are to be looked at anew as an opportunity and self-confidence is to be gained. A scheme that highlights positive and negative aspects of role changes can help here. There is ample evidence for the efficacy of IPT in the acute treatment of unipolar depressive disorder as a sole therapeutic modality or as part of a combination modality with antidepressant medication.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2017; 15(2): 17-21.