Psychological trauma can have different causes. However, they have one thing in common – they would cause profound despair in almost anyone. Traumatic experiences can be classified according to different aspects and treated individually.

The characteristics of psychological trauma and therapeutic approaches to its treatment are presented below. Special attention will be given to the most important symptoms and most effective interventions. The concise summary of current research findings makes this article especially suitable for practitioners. The reference to therapy manuals and studies also provides the opportunity for further in-depth study.

Traumatic events

Psychological trauma is defined in ICD-11 as an event or series of events of extraordinary threat or catastrophic magnitude that would cause profound distress to almost anyone [1]. The U.S. DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) system describes trauma as events involving confrontation with death, serious injury, or sexual violence [2]. Direct experience, personal witnessing, occurrence in close family or with close friends, and repeated confrontation with aversive details (e.g., in the context of one’s job) are specified as 4 possible forms.

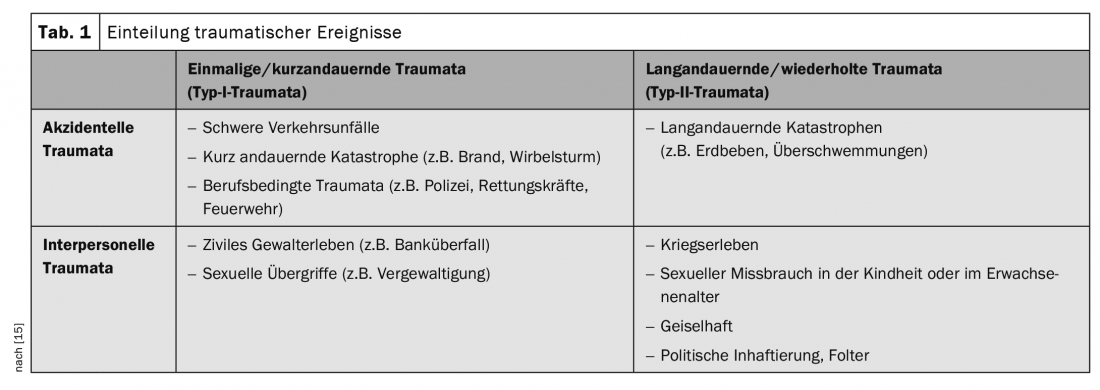

Traumatic events can be classified according to various aspects. As an orienting scheme, the division into man-made versus accidental trauma and into short versus long-term trauma (type I versus type II) has proven useful (Table 1). Type I traumas are usually characterized by acute danger to life, suddenness and surprise, type II traumas by series of different traumatic individual events and by a low predictability of the further stressful events.

Across all trauma types, there is a conditional probability of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) of 8-15%. That is, for every 100 traumatized individuals, 8-15 have a PTSD diagnosis. However, with respect to the different types of trauma, the conditional probability varies considerably:

- About 50-65% after direct experience of war as a civilian;

- about 50% after rape and sexual abuse;

- about 25% after other violent crimes;

- about 5% after serious traffic accidents;

- <5% after natural, fire, or fire-related disasters;

- <5% for witnesses of accidents and violent acts.

The post-traumatic stress disorder

“Since the attack I have become a completely different person,” reports a 60-year-old man, “in the evening I lie in bed, and then these thoughts and images come, and then I lie awake forever. (…). If I’m somewhere and there’s a sudden noise, I flinch. (…) You can’t turn it off.” The man, victim of an assault, suffers from so-called PTSD. The presence of severe trauma is a prerequisite for a diagnosis of PTSD. It is diagnosed when some individual symptoms occur together over a long period of time. According to the latest definition of the ICD-11, the symptoms focus on the vivid re-experiencing of the traumatic situation (intrusion), avoidance, and a persistent feeling of threat.

Intrusion: patients with PTSD exhibit an involuntary attachment to the horrific experience. This bondage manifests itself in images, sounds, or other vivid impressions of the traumatic event that inadvertently “intrude” into both the waking state of consciousness and sleep. This is also called flashbacks. Often there is a subjectively experienced flooding state by these inner images.

Avoidance: In addition, those affected often try with all their might to “switch off” the thoughts that flood them, i.e. to stop thinking about what happened. Despite intensive attempts, this avoidance does not succeed in most cases. Avoidance behaviors also include shying away from doing activities, going places, or meeting people who are reminders of the trauma.

Persistent feeling of threat: The body reacts with after a trauma, even if the affected persons often do not see the physical consequences in connection with the trauma. The excitation threshold of the autonomic nervous system lowers, i.e. even smaller subsequent stresses lead to stronger excitation. As a result of the trauma, a persistent feeling of threat sets in (hypervigilance). Everyday situations are perceived as excessively dangerous. This applies to both trauma-associated and unrelated situations.

Epidemiology and course of PTSD: Although epidemiological studies show that most of the population experiences traumatic events during their lifetime, the lifetime prevalence in Europe is only between 1 to 3 percent [3]. That is, most trauma victims do not develop PTSD but show spontaneous recovery. The course of PTSD is also characterized by the fact that in the majority of trauma victims the symptoms remit within a few weeks. A duration of symptoms of more than three months is prognostically unfavorable, as the symptoms persist for a longer time and become chronic.

Complex PTSD

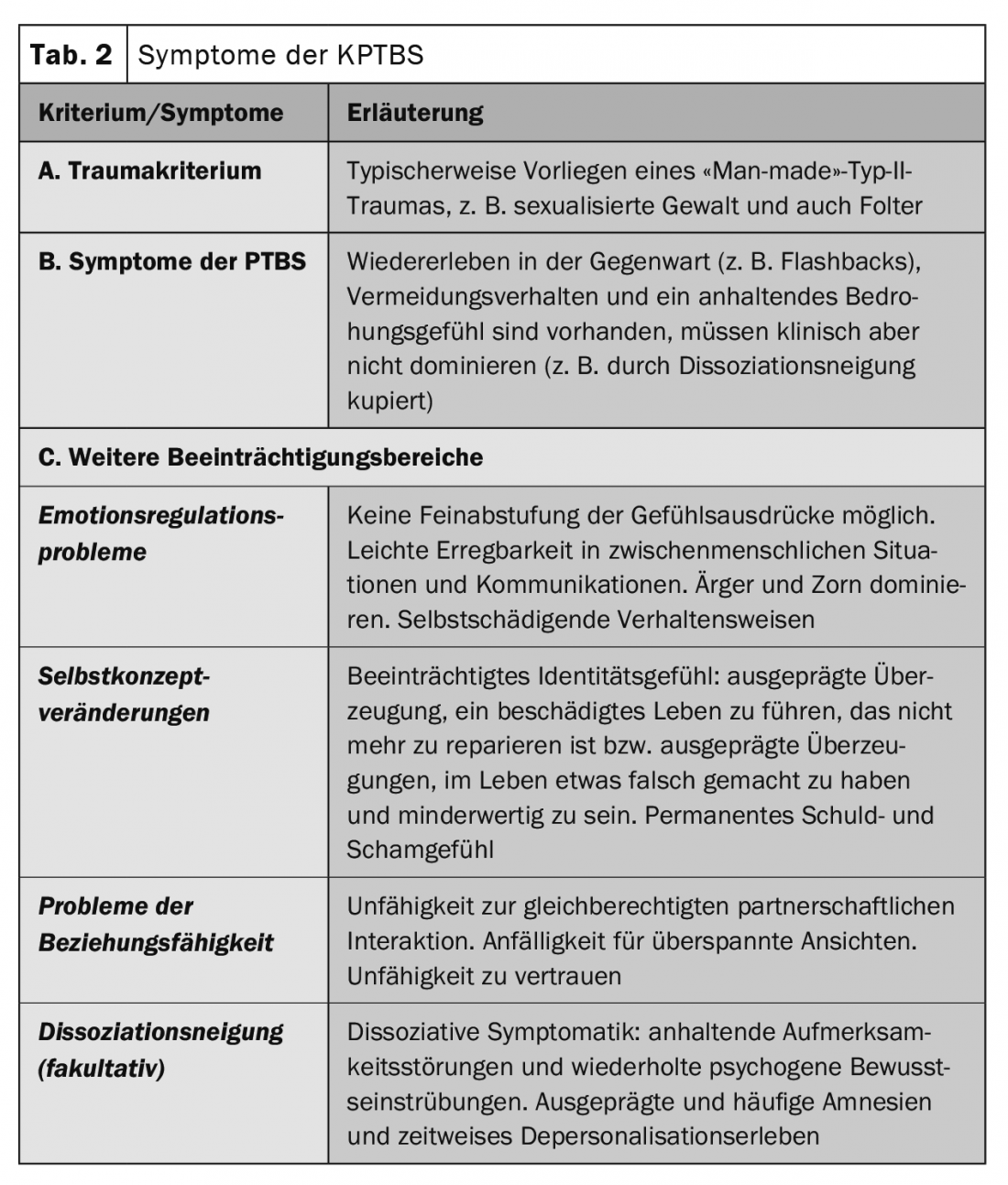

The same psychological symptoms have been described for all traumas. However, volitional human-induced trauma and Type II trauma of longer duration have been shown to result in more extensive impairments than the other forms in many cases. Therefore, complex PTSD (KPTBS) was introduced as a new diagnosis in ICD-11. Complex PTSD involves a strong psychological reaction caused by persistent traumatic experiences, usually involving multiple or repetitive traumatic events (e.g., childhood sexual abuse). The diagnosis includes all the main symptoms of classic PTSD. In addition, an affect regulation disorder (including dissociation tendency), negative self-perception, and relationship disturbances must be present for a diagnosis of KPTBS (Table 2).

Psychotherapy

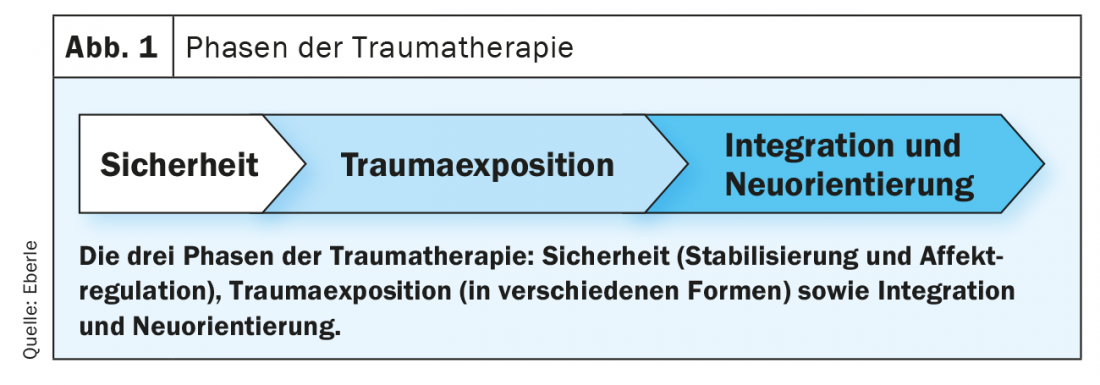

In the last two decades, successful methods for the therapy of post-traumatic reactions and manifest trauma sequelae have been developed. Important to keep in mind when treating PTSD is that many patients have a number of other psychological and interpersonal problems (depression, addictions, physical illness, social withdrawal). In the German-speaking world, three therapy phases have become established in the treatment of PTSD (Fig. 1).

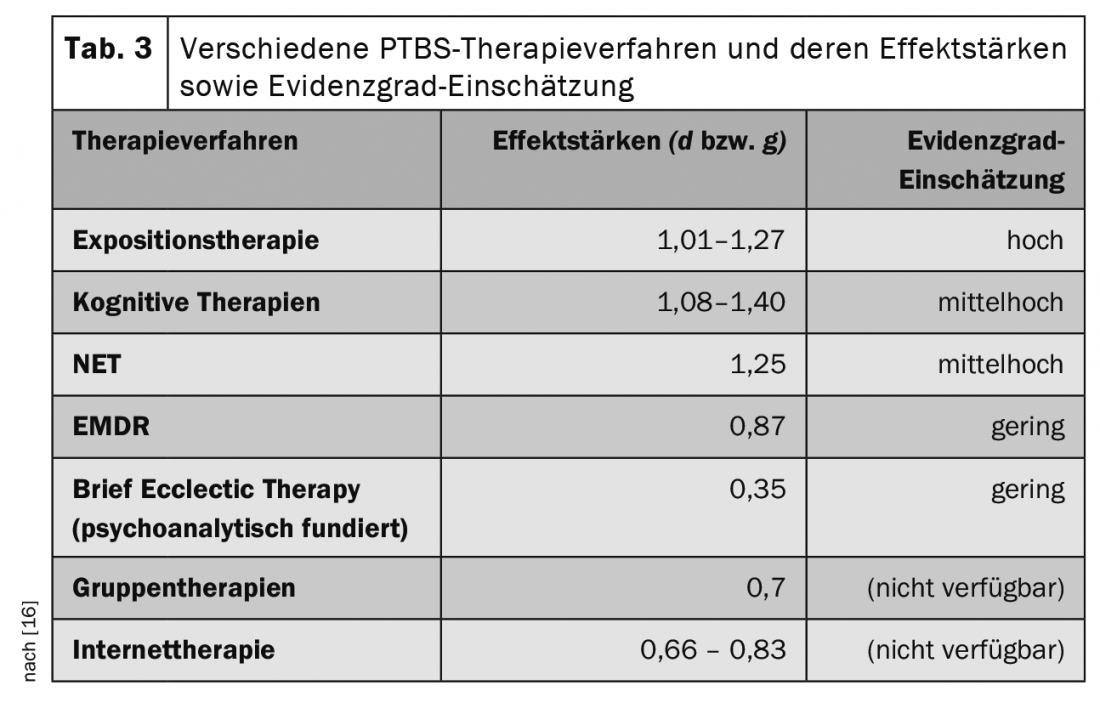

Behavioral approaches (e.g., Prolonged Exposure) and cognitive therapies have the highest effect sizes among all PTSD treatment modalities (Table 3) . Narrative exposure therapy (NET) and EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) are also common treatment approaches. Results from research further show that psychotherapy has a higher efficacy than drug treatment (e.g., escitalopram) [4].

Exposure to the traumatic event is the focus of psychotherapies evaluated as successful. In prolonged exposure therapy, patients with PTSD are imaginatively confronted with traumatic events [5]. The trauma is relived and narrated with the help of one’s own feelings. Through this exposure in sensu (in the imagination), the traumatic event is reported repeatedly until habituation occurs, i.e., habituation with attenuated response when confronted with memories of the trauma. In some cases, this approach is combined with exposure in vivo to avoided situations.

Cognitive processing therapy is another element of trauma therapy. Individuals with PTSD are often characterized by an extremely negative evaluation of posttraumatic symptoms [6]. For example, persistent intrusion symptoms may be interpreted in a catastrophizing manner (e.g., “If these sudden memories don’t stop soon, I’ll eventually go crazy!”). It is also not uncommon for individuals to exhibit strong guilt beliefs following trauma. Cognitive interventions focus on the modification of dysfunctional evaluations and beliefs using classical cognitive techniques [7].

Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET) was developed for the treatment of PTSD following multiple traumas and is based on cognitive-behavioral therapy principles. With NET, there is no selective processing of a trauma, but the entire life span is narratively represented and written down. By placing one or more traumas chronologically in one’s own biography, confrontational processing occurs [8]. The EMDR method (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) according to Shapiro is also a common method in trauma therapy. In EMDR exposure, images, perceptions, cognitions, or feelings associated with the trauma are processed with bilateral sensory stimulation via eye movements (or auditory or tactile stimulation) until the distress is reduced [9].

Exposure therapy, in particular, often succeeds in reducing post-traumatic symptoms in a matter of weeks. Beyond symptom reduction, dealing with the multiple consequences and integrating the trauma into the trauma victim’s life requires prolonged therapeutic work. Basically, the exposure procedure (i.e., visualization of the trauma together with the psychotherapist) is to be distinguished from retraumatization, since the former serves an underpinning and healing purpose and offers the patient possibilities of restructuring his traumatic memory content. Retraumatization, on the other hand, is defined as a procedure that only re-stresses or severely overburdens the patient and does not provide any goal-oriented relief (retraumatizations are, for example, results of unfavorably conducted police interrogations or interviews with sensational journalists).

Approach to complex PTSD: P TSD poses particular challenges to psychotherapists and many unanswered questions still exist regarding the therapeutic approach, the duration of treatment and the expected treatment success. However, there is agreement that successful treatment of PTSD requires exposure in sensu in combination with cognitive procedures, analogous to PTSD. This was demonstrated by Watts et al. [10] confirmed in an extensive meta-analysis. However, the exposure must be preceded by a sufficiently long phase of stabilization. However, this phase can also be very short if intensive treatment is provided, as has been demonstrated using the inpatient 12-week Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) approach to PTSD [11]. After only one month of stabilization, confrontation was successfully carried out with complex traumatized persons. Some particularly severely affected patients, however, may require multiple changes between outpatient and inpatient interventions until therapeutic success is achieved.

As described earlier, in addition to symptoms of PTSD, individuals with KPTBS often exhibit problems with emotion regulation and interpersonal problems. By implementing DBT strategies into the therapeutic process, emotions can be effectively regulated, making this approach particularly suitable for KPTBS [12]. Cloitre et al. developed a 2-step phase-oriented therapy program that integrates effective interventions for multiple symptom domains [13]. The first phase of treatment focuses on skills for emotion regulation and the processing of dysfunctional interpersonal schemas (“skills training in affect and interpersonal regulation”, STAIR). In the second phase of treatment, traumatic memories are processed gently and in measured doses with the help of narrative methods. This phased approach proved to be very effective with victims of sexual and physical abuse, for example [14].

Take-Home Messages

- PTSD occurs after life-threatening/traumatic life events and is characterized by intrusions (in the form of imposing images or nightmares), avoidance, and a persistent sense of threat.

- PTSD occurs particularly as a result of repetitive or prolonged traumatic events and, in addition to the symptoms of PTSD, is additionally characterized by emotion regulation disorders, negative self-perception, and relationship disturbances.

- Various forms of exposure in sensu to the traumatic event are the focus of psychotherapies for PTSD that have been evaluated as successful.

- Successful treatment approaches to PTSD should include exposure in sensu, analogous to classic PTSD. Complementary interventions such as STAIR or DBT-PTBS are particularly promising for KPTBS.

Literature:

- WHO (World Health Organization). (2020). ICD-11 beta draft (mortality and morbidity statistics). https://icd.who.int/dev11/l-m/en. Accessed 12/16/2020.

- APA (American Psychiatric Organization). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-V). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Maercker A, Forstmeier S, Wagner B, et al: (2008). Posttraumatic stress disorders in Germany. Der Nervenarzt, 79(5), 577.

- Shalev AY, Ankri Y, Israeli-Shalev Y, et al: (2012). Prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder by early treatment: results from the Jerusalem Trauma Outreach and Prevention study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(2), 166-176.

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Rothbaum BO: (2014). Handbook of Prolonged Exposure: Basic Concepts and Application – A Guide for Therapists. Lichtenau: Probst.

- Ehlers A, Clark DM: (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(4), 319-345.

- King J, Resick PA, Karl R, Rosner R: (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder: a Cognitive Processing Therapy manual. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

- Schauer M, Neuner F, Elbert, T: (2011). Narrative exposure therapy: A short term intervention for traumatic stress disorders after war, terror, or torture. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

- Shapiro F: (2012). EMDR – Fundamentals and Practice: Handbook for the Treatment of Traumatized People. Paderborn: Junfermann.

- Watts BV, Schnurr PP, Mayo L, et al: (2013). Meta-analysis of the efficacy of treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(6), 541-550.

- Bohus M, Dyer AS, Priebe K, et al: (2013). Dialectical behaviour therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder after childhood sexual abuse in patients with and without borderline personality disorder: A randomised controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(4), 221-233.

- Bohus M, Priebe K: (2019). Dialectical-behavioral therapy for complex PTSD. In A. Maercker (Ed.). Trauma sequelae disorders (pp. 331-348). Berlin: Springer.

- Cloitre M, Koenen KC, Cohen L, et al: (2002). Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: a phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 1067-1074.

- Cloitre M, Cohen LR, Koenen KC: (2014). Childhood sexual abuse and maltreatment: a therapy program to address complex trauma sequelae. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

- Maercker A, Augsburger M: (2019). Post-traumatic stress disorder. In A. Maercker (Ed.). Trauma sequelae disorders (217-227). Berlin: Springer.

- Maercker A: (2019). Systematics and effectiveness of therapeutic methods. In A. Maercker (Ed.). Trauma sequelae disorders (pp. 217-227). Berlin: Springer.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(7): 5-8