Surgical resection represents the mainstay of therapy for pelvic bone sarcomas. Treatment is complex and should be individualized. By sharing data and expert knowledge, the disease can be better understood. One approach to this is the SwissSarcomaNetwork.

Primary malignant bone tumors, so-called sarcomas of the bone, are rare, and their diagnosis and therapy also require a high degree of interdisciplinarity and coordination. Depending on the age, the extent of the disease and the anatomical location and size of the tumor, the treatment must be individualized. Surgery is the mainstay of therapy and microscopically complete resection is directly correlated with survival.

According to the Rizzoli Institute (www.ior.it), 16.5% of all primary malignant bone tumors are found in the pelvis. The most common include chondrosarcoma (5.3%), Ewing’s sarcoma (4.8%), osteosarcoma (3.2%), and chordoma at 2%. The age and sex distribution is usually based on the underlying biology of the tumor.

Clarification of a pelvic sarcoma

The workup of pelvic bone sarcomas is complex because the tumor-especially if it grows intrapelvically-is often inaccessible to palpation for long periods of time, and pain is usually initially classified as nonspecific. Mainly, pain is influenced by the anatomic location of the finding, rather than the underlying biology. It is not uncommon for pelvic sarcomas to be relatively large by the time of diagnosis. Therefore, it is important to consider the diagnosis of pelvic sarcoma as a differential diagnosis in the first place [14].

A pelvic overview radiograph may already show contour blurring, which may be indicative of a pelvic tumor. Larger tumors show the extent of bone destruction, and thus allow a basic assessment of mechanical stability. I.v. contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI-KM) is the method of choice to adequately characterize the lesion. The anatomical location in the pelvis should be assessed, as well as the relationship to the neurovascular structures, periosteum, and articular structures. The contrast image provides information about the blood flow to the lesion and thus its potential aggressiveness.

If the suspicion of bone sarcoma still cannot be ruled out on imaging, a biopsy should always be ordered. The choice of biopsy route is critical and must be made in such a way that it can be removed during subsequent surgery without avoidable tissue contamination and unnecessary opening of additional compartments to minimize tumor cell seeding and thus the risk of local recurrence. Preferably, the biopsy is performed by a well-rehearsed clarification unit of interventional radiologist, pathologist and surgeon. To minimize tumor cell seeding, a punch biopsy should be performed because, in contrast to open biopsy (at 32%), the risk is significantly lower at 0.37% [1,2].

The workup of a biopsy specimen is critical and should at least be cross-read by a reference pathologist. Molecular analyses are nowadays part of the standard initial clarification, but cannot be offered or interpreted everywhere. An initial workup in a clarification unit with reference pathologists also helps to prevent unnecessary delays for the patient in establishing the diagnosis. Once the malignancy of a finding is confirmed, a “staging” examination should be performed to rule out metastasis to the lungs (by computed tomography) or else bones (skeletal scintigraphy, PET-CT, or whole-body MRI).

Neo-adjuvant treatment

Neo-adjuvant treatment of pelvic sarcoma is based on the biology of the tumor [12]. Chondrosarcomas are usually resistant to radiation and chemotherapy, and surgery remains the treatment of choice; (neo-)adjuvant therapy is not necessary. Patients with Ewing’s sarcoma usually undergo combination therapy, beginning with preoperative VIDE induction therapy (https://sarcoma.surgery/pdf/ewing-sarkom ) for approximately 16 weeks, followed by surgery, and then eight VAC cycles for an additional 23 weeks. The indication for concomitant radiotherapy is undergoing a change in which increasingly it is now being performed for R0 resections [11].

Patients with osteosarcoma are also treated by combination therapy. Induction chemotherapy includes adriamycin, cisplatin, ifosfamide, and high-dose methothrexate, according to the EURAMOS study protocol, with continuation of therapy after surgery risk-adapted. Chordomas are often locally advanced, and historically treatment has been based on either surgery or in combination with radiation therapy. Particle-ion radiotherapy may provide an effective alternative to surgical resection, although no robust and comparative studies are available. Systemic treatments such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors are being evaluated [12].

Resection types

Surgical therapy is the mainstay of treatment for primary pelvic malignancies with curative intent. The extent of pelvic surgical resection depends on the anatomic extent of the tumor and must be defined, planned, and performed based on preoperative MRI imaging. The goal is to microscopically remove the tumor completely, regardless of biology (even for a chondrosarcoma G1, for example), with adequate safety distance, taking into account anatomical barriers (without defining a metric measure).

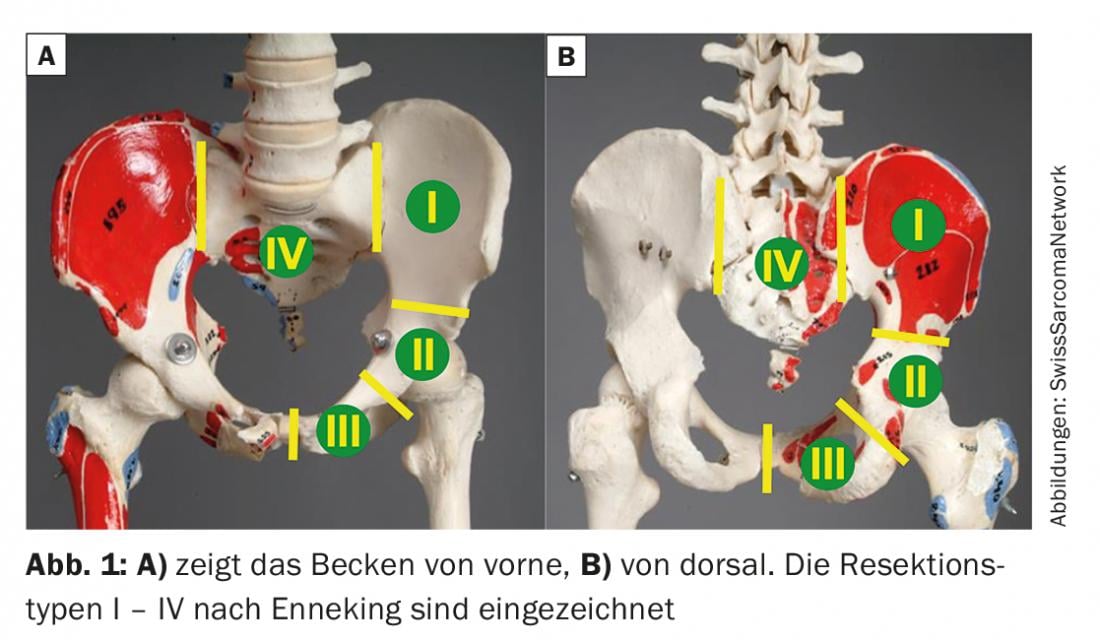

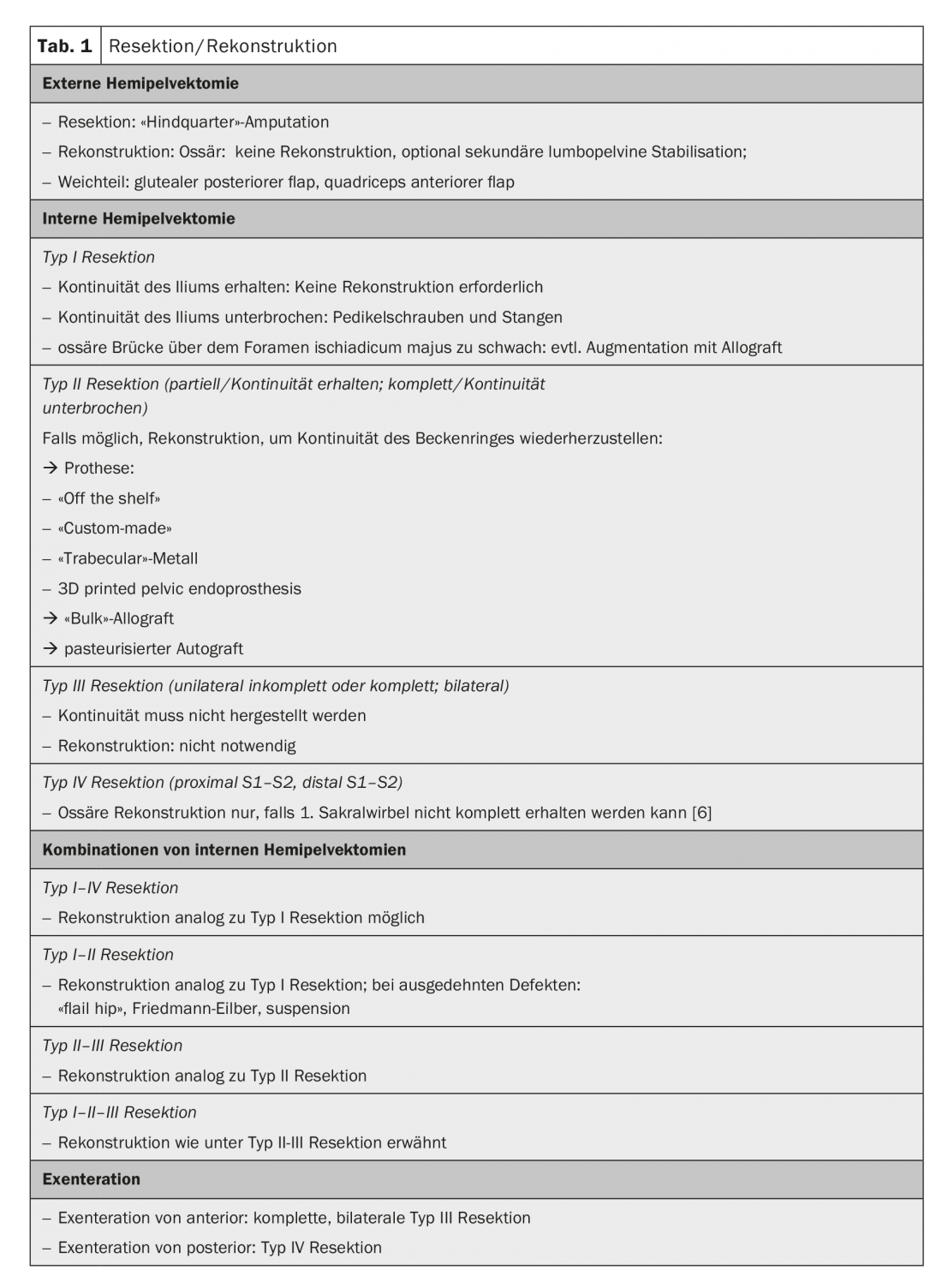

Surgical resections of the pelvis – or hemipelvectomies in the technical term – are divided into internal and external hemipelvectomies. In the latter, the associated limb is also removed, a so-called “hindquarter” amputation. Regarding indication, tumor infiltration of hip joint, of nerve structures (ischiadicus nerve) as well as of vascular structures (A.V.iliaca communis and branches) must be assessed. If at least two of the three mentioned structures must be resected due to tumor infiltration, external hemipelvectomy is usually considered. Partial pelvic resections with preservation of the lower extremity are called internal hemipelvectomies. According to Enneking, these are divided into four types, with various combinations possible (Fig. 1) . Type I resections can be performed with or without interruption of the pelvic ring, and extend from the SI joint to the acetabulum. Type II resections refer to the acetabulum, and type III resections to the pubis. They can be partial or complete, depending on the extent of the tumor. Pelvic sarcomas may cross the SI joint, requiring type I-IV resection, or type I-II, type II-III, or type I-II-III resection if infiltrating the acetabulum or pubis. For resections of the sacrum (type IV resections), the proximal tumor extent in particular must be detected on imaging. The level of osteotomy is then based on the relationship of the tumor to the nerve roots, which can be preserved to the maximum extent with adequate safety margin. Depending on the tumor extent, a co-resection of the ilium must be considered (type IV-I resection).

Resections of the pelvis are anatomically complex, which is why either navigation or patient-specific incision implants (PSI) are often used for the operations [15,16]. This allows the incisions to be made with millimeter precision after prior 3D planning.

Reconstructions

External hemipelvectomies usually do not require osseous reconstruction. If secondary scoliosis develops, associated with clinical symptoms, stabilization of the lumbo-pelvic junction may be considered. The soft tissues are often covered with a gluteal soft tissue flap. Even if the internal iliac veins have to be ligated due to tumor extension, blood flow to this lobe is usually ensured. Alternatively, the omentum majus can be used as a vascularized soft tissue flap. For main tumor extension to gluteal extrapelvic, the anterior soft tissue flap of the quadriceps muscles is preferred for soft tissue coverage, based on the femoral vessels.

For internal hemipelvectomies, the type of reconstruction depends on the extent of the resection. The reconstruction itself must be individualized on a patient-by-patient basis, and depends on many other factors such as the age of the patient or the presence of metastases.

Type I resection does not require reconstruction as long as the pelvic ring is preserved. If the osseous bridge over the foramen ischiadicum majus is too weak, an allograft or autograft from the rest of the pelvis can be used for reinforcement. If continuity is interrupted, reconstruction should be performed whenever possible. Here, the goal is to achieve immediate mechanical stability by pedicle screws (lumbar and sacral as well as in the anterior and posterior pillars) and rods, and additionally to achieve biological long-term stability by inserting a (non)vascularized fibula autograft or else allograft so that normal function can result [7].

In type II resections, reconstruction should be performed when possible to restore pelvic ring continuity and thereby improve pelvic stability and hip joint function. Various options for reconstruction are available, the choice of which depends, among other things, on the local extent of resection. “Off-the-shelf” prostheses can be used as long as there is sufficient bone at the ilium to allow secure anchorage. Alternatively, “custom-made” prosthetic options are available, where the implant company 3D prints the prosthetic implant based on a CT scan to reflect the patient’s specific anatomy. Alternatively, “trabecular” metal can be used, where the missing bone portion can be built up intraoperatively so that a prosthesis can be fitted. As an alternative to prosthetic reconstruction, a “bulk” allograft in the sense of an allograft-prosthesis composite can be used. Due to the nevertheless considerable complication rate, this option is used less frequently nowadays. Pasteurized autograft is used as another but very specific option. Once the resection is complete, the tumor is curetted and the macroscopically tumor-free specimen is irradiated extracorporeally with 50-90 Gy, optionally augmented with cement, and reinserted in the patient [8].

Type III resections of the pelvis can be either unilateral or bilateral. The former are further divided into complete and incomplete, depending on whether the pelvic ring is maintained in continuity or not. Reconstruction is not necessary in all situations.

Type IV resections involve the sacrum, with the level of osteotomy referring to the corresponding sacral vertebra or associated nerve root. Distal S2-S3 is usually operated from the dorsal side only; if the osteotomy is proximal, it is recommended to approach from anterior and posterior combined. Osseous reconstruction is only necessary if the first sacral vertebra cannot be completely preserved [6]. Resection distal to S3 usually shows no functional deficits, whereas resections including the S2 nerve roots can lead to permanent impairment of bladder and bowel emptying, which is very debilitating for the patient. Unfortunately, reconstructions of these nerve roots showed no functional gain. However, wound healing disorders are frequently observed during these operations. Therefore, the indication for soft tissue reconstruction should be generous, such as. gluteal displacement flap, a lumbar perforator flap, or else a transabdominal VRAM flap. However, pelvic tumors are often relatively large and occupy more than one of the above zones, requiring a combination of resection types.

In type I-IV (or IV-I) resection, reconstructions can be performed in a manner analogous to type I resections.

For type I-II (or II-I) resections, decisions must be made on an individual basis; reconstructions are analogous to those listed under type I resections. The critical point, however, is the location of the osteotomy at the sacroiliac joint. Although CT-based 3D-printing allows any defect to be anatomically accurately restored by a “custom-made” prosthesis, in the case of vertical osteotomy, stability is practically impossible to achieve in the long term for mechanical reasons and implant failure is the rule. For this reason, a “flail hip” or so-called Friedmann-Eilber resection arthroplasty [10] is often used for extensive defects. One modification is the use of two Trevira tubes, the first fixed from the femur to the sacrum, and a second forming a loop around it, pulling from the superior pubic ramus to the ischium, resulting in a suspension (Fig. 2).

- Type II-III (or III-II) resections are reconstructed analogously to type II resections.

- Type I-II-III resections are reconstructed as mentioned under type II-III resections.

Exenterations occupy a special position. Posterior exenteration is usually first performed from anteriorly by laparotomy and dissection of the tumor intraperitoneally and/or retroperitoneally, and then the patient is repositioned and completed from dorsally by sacrectomy. Anterior exenteration also begins with laparotomy and dissection of the tumor to then expose the pelvic isthmus after extrapelvin to complete by bilateral symphysectomy (or type III resection).

Surgical challenges and outcome

Surgical resections of the pelvis are challenging and require great understanding in planning as well as optimal interdisciplinary collaboration in implementation. The principle is that the greater the safety distance, the greater the potential tumor control and the greater the potential functional loss. In addition, the safety distances cannot be defined in the extremities as usual, since there are no corresponding compartments. Regarding function, it must be taken into account that reconstruction of the pelvic ring does not necessarily lead to good function. This is because resection of the abductor muscles or a nerve root or major nerve can lead to significant functional losses.

Patients with osteosarcoma of the pelvis have a relatively poor prognosis with a 5-year survival of approximately 40% [5]. Interestingly, the value of neoadjuvant chemotherapy has even been questioned [13]. Patients with Ewing’s sarcoma of the pelvis achieve a 5-year survival of 37% [9]. In patients with chondrosarcoma, survival is directly correlated with grading. The mortality rate is 3% in G1, 33% in G2, and 54% in G3, with a direct negative correlation between resection safety margins and tumor size in addition to grading [3]. The same relationship holds true for patients with sacral chordomas, with a 5-year survival rate of 74% [4].

Outlook

Despite maximal combination therapy, pelvic sarcomas continue to be associated with poor prognosis. Surgery is the mainstay for localized disease, and incomplete tumor resection correlates with poor tumor control, often leading to death. To better understand these diseases, we need better interdisciplinary exchange locally as well as nationally and internationally. This requires a solution from classical thinking in disciplines (so-called “discipline-centered medicine”), to “problem-centered medicine” in order to treat our patients in the best possible way. One approach to this is the SwissSarcomaNetwork (www.swiss-sarcoma.net).

Take-Home Messages

- Bone sarcomas of the pelvis are rare, and the prognosis compared to bone sarcomas of the extremities is poorer.

- The workup and treatment of patients with pelvic bone sarcomas require a high degree of interdisciplinarity and coordination.

- Surgery is the mainstay of therapy, especially in localized disease.

- The disease can be better understood through the supraregional or international exchange of data and expert knowledge.

Literature:

- Barrientos-Ruiz I, et al: Are Biopsy Tracts a Concern for Seeding and Local Recurrence in Sarcomas? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017; 475: 511-518.

- Berger-Richardson D, Swallow CJ: Needle tract seeding after percutaneous biopsy of sarcoma: risk/benefit considerations. Cancer 2017; 123: 560-567.

- Bus MPA, et al: Conventional Primary Central Chondrosarcoma of the Pelvis: Prognostic Factors and Outcome of Surgical Treatment in 162 Patients. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 2018; 100: 316-325.

- Fuchs B, et al: Operative management of sacral chordoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87: 2211-2216.

- Fuchs B, et al: Osteosarcoma of the pelvis: outcome analysis of surgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009; 467: 510-518.

- Hugate RR, et al: Mechanical effects of partial sacrectomy: when is reconstruction necessary? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 450: 82-88.

- Krieg AH, Hefti F: Reconstruction with non-vascularised fibular grafts after resection of bone tumours. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007; 89: 215-221.

- Krieg AH, Mani M, Speth BM, Stalley PD: Extracorporeal irradiation for pelvic reconstruction in Ewing’s sarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009; 91: 395-400.

- Laitinen M, et al: Outcome of Pelvic Bone Sarcomas in Children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016.

- Schwartz AJ, et al: The Friedman-Eilber Resection Arthroplasty of the Pelvis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467: 2825-2830.

- Whelan J, et al: Survival is influenced by approaches. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2018:1-13.

- Whelan JS, Davis LE. Osteosarcoma, Chondrosarcoma, and Chordoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018; 36: 188-193.

- Xu J, Xie L, Guo W: Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Followed by Delayed Surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2018: 1.

- Fuchs B, et al: Pretherapeutic assessment and strategy determination in patients with bone and soft tissue tumors. Luzerner Arzt 2017; 109: 1-5.

- Jentzsch T, et al: Tumor resection at the pelvis using three-dimensional planning and patient-specific instruments: a case series. World J Surg Oncol 2016 14(1): 249.

- Sternheim A, et al: Cone-beam computed tomography-guided navigation in complex osteotomies improves accuracy at all competence levels: a study assessing accuracy and reproduciblitiy of joint-sparing bone cuts. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2018: 100 (10).

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2018; 6(5): 8-12.