A man presents to the pulmonary clinic with wheezing and shortness of breath. He has had asthma since childhood, which has so far been controlled with medication. The patient reports daily symptoms and regular nighttime awakenings due to dyspnea, which is temporarily relieved by bronchodilators. But behind the asthma two other disease patterns were hiding.

The patient has had several exacerbations in the past six months and was hospitalized a month ago after an episode, write Emily Norder, M.D., and Maria Lucarelli, M.D., of the Department of Internal Medicine at Ohio State University Medical Center in Columbus [1]. The man was treated with reducing doses of oral prednisone at each exacerbation and reported that his symptoms worsened after each steroid reduction.

His medical history also includes several years of allergies and chronic sinusitis that required three surgeries. At the time of presentation, his current medications included: fluticasone/salmeterol 500 μg/50 μg twice daily, zileuton 1200 mg twice daily, prednisone 10 mg daily, montelukast 10 mg once daily, and albuterol as needed, which he was using four times daily at the time.

Omalizumab 300 mg/month was started 4 months ago, but without significant improvement. The patient is a lifelong nonsmoker and denies any illicit drug use.

Physical examination

On physical examination, vital signs are normal with Spo2 of 95% on room air. His pulmonary examination shows significant diffuse expiratory wheezing with prolonged expiratory phase. Cardiac examination shows regular rate and unremarkable rhythm.

Further investigation revealed that the patient during his last sinus surgery (before his asthma worsened) showed pathology and culture allergic mucin and non-invasive Aspergillus along with allergic fungal sinusitis. The laboratory tests showed:

- Leukocyte count (WBC) 8.4 K/μl with 25% eosinophils, absolute eosinophils 2.1 K/μl (normal 0-0.5 K/μl).

- Hemoglobin, platelets and chemical values including renal function were normal

- Serum IgE level: 931 IU/ml (normal 7-135 IU/ml) after omalizumab for approximately 2 months.

- Serum Aspergillus IgE: 1.53 kμ/l

- (positive 0.71 to 3.50)

- Skin test for Aspergillus: negative

In such patients, it is important to consider other conditions that can mimic asthma and therefore lead to poorly controlled symptoms despite appropriate asthma therapy, Norder and Lucarelli explain. These include bronchiolitis obliterans, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), Churg-Strauss, and vocal cord dysfunction. Evaluation and therapy of atopy, rhinosinusitis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease should also be completed.

Diagnosis

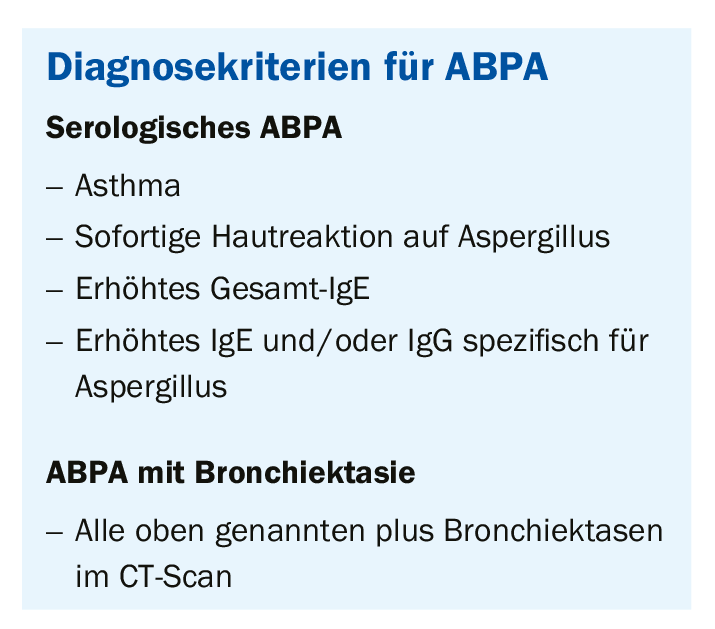

The physicians diagnosed allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and allergic fungal sinusitis (AFS). ABPA is characterized as a hypersensitivity reaction to non-invasive Aspergillus in the respiratory tract, consequently repeated episodes of inflammation and mucosal disturbances lead to bronchiectasis, fibrosis and progressive loss of lung function. It is estimated that ABPA affects 3-5% of patients in asthma clinics and 7-14% of corticosteroid-dependent asthmatics in the United States. The clinical presentation is inconsistent but is most commonly seen in severe asthma or cystic fibrosis. Patients often have recurrent episodes of wheezing, fever, pleuritic chest pain, and mucus congestion associated with elevated IgE levels, peripheral eosinophilia, and infiltrates on chest radiograph. This diagnosis should be considered in asthma patients with refractory symptoms despite appropriate treatment or when there is evidence of clinical data such as infiltrates or bronchiectasis on imaging, peripheral eosinophilia, or positive sputum culture or skin tests for Aspergillus. Currently, there are several diagnostic criteria for ABPA in the literature. One approach separates the diagnosis of serologic ABPA from ABPA with central bronchiectasis (Box 1).

An incidence of 5-10% is estimated for AFS in patients undergoing sinus surgery for chronic disease. The diagnosis is usually made on the basis of radiological, clinical and histopathological findings. Diagnostic criteria for AFS were developed in 1995 (Box 2). Peripheral eosinophilia, elevated total IgE and fungal-specific IgE and IgG, and positive skin tests suggest AFS in the appropriate context but are not part of these diagnostic criteria.

“Our patient met the criteria for ABPA and AFS,” Norder and Lucarelli write. In the literature, he said, there are few case reports of ABPA and AFS occurring together. Each disease is characterized by a hypersensitivity reaction to the presence of a noninvasive fungus and the production of thick mucus plugs. Both have similar histologic findings with extramucosal, allergic, mucinous eosinophils as well as fungal elements. Serum tests can detect elevated total IgE, fungus-specific IgE and IgG, and positive skin tests with immediate hypersensitivity to the etiologic fungus in both ABPA and AFS. Furthermore, for both ABPA and AFS, total IgE appears to correlate with disease activity and may be addressed with treatment.

It has been shown that in patients who have both ABPA and AFS, it is variable which diagnosis is made first. The time between diagnoses can be up to 10 years. Some sources suggest that the prevalence of coexisting conditions may be underestimated because of the involvement of different specialists (e.g., a pulmonologist for ABPA and an otolaryngologist for AFS) caring for the patient.

Therapy

First choice in ABPA treatment remains corticosteroids, although this is not an ideal long-term strategy. In acute exacerbation, high-dose steroids should be administered for months and gradually reduced, depending on the patient’s response. If possible, the steroid should be discontinued altogether. If the patient cannot be weaned off steroids, he is considered steroid dependent and treatment with antifungals should be considered.

The primary antifungal agent used to date is itraconazole. In 2000, a randomized, double-blind trial of itraconazole versus placebo was conducted in patients with corticosteroid-dependent ABPA [2]. Response rates defined as a reduction in steroid dose by at least 50%, a reduction in IgE by at least 25%, and either resolution of infiltrate, improvement in exercise tolerance by at least 25%, or increase in one of the five pulmonary function tests (FEV1, FVC, DLCO Peak flow or FEV in the mid-expiratory phase) were significantly higher in the treatment group compared with placebo (46% versus 19%). Based on this study, itraconazole should be considered for add-on therapy in patients with steroid-dependent disease. The role of itraconazole in acute symptoms or exacerbations is unclear.

The treatment of allergic fungal sinusitis is less well defined and combines a medical and surgical approach. No well-controlled or randomized trials have been conducted to investigate potential treatments for AFS. Surgery is almost always required to remove polyps and inflammatory material (and to allow better drainage). However, this intervention has a very high recurrence rate. The use of corticosteroids after surgery has been largely derived from what is known about the treatment of ABPA and applied to AFS. Antifungal agents do not have a clear role in the treatment of AFS.

Literature:

- Norder E, Lucarelli M: Difficult-to-Control Asthma in a 49-Year-Old Man. ATS online

- Stevens DA, et al: N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 756-762.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2020; 2(2): 38-40.