Diabetes is associated with increased cardiovascular risk. Multifactorial therapy of the four major risk factors of blood glucose, weight, hypertension, and dyslipidemia in individuals with type 2 diabetes is challenging. However, it has been shown that diabetics can benefit greatly from modern treatment options. Effective “add-on” therapeutic options are available for lipid lowering with ezetimibe and PCSK-9 inhibitors. Study data show that PCSK-9 inhibitors contribute to additional lipid lowering in patients with and without diabetes.

Adult diabetics are two to four times more likely to have a cardiovascular event such as ischemic stroke or nonfatal myocardial infarction than healthy individuals, and cardiovascular disease accounts for up to 50% of diabetes-associated deaths [1,2]. High LDL cholesterol levels are among the main risk factors, along with inadequate glycemic control, obesity, and hypertension [3]. That cholesterol levels are a relevant factor and that diabetic patients can benefit from lipid lowering is evident from data from various prospective and randomized studies, explains Prof. Gottfried Rudofsky, MD, Chief Physician, Metabolic Center, Olten Cantonal Hospital [4].

What are the treatment goals recommended by the ESC?

The goal of lipid-lowering treatment is to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events as much as possible. Studies in recent years show that the lower the LDL-C, the lower the cardiovascular risk. Accordingly, there is no lowest LDL-C concentration limit below which cardiovascular risk does not decrease further. This has been incorporated into the 2019 revised ESC/EAS guidelines, with expert recommendations focusing on high-risk patients [5]. Most diabetics are considered high-risk patients with regard to cholesterol-lowering therapy, in whom a target range of <1.8 mmol/l should be aimed for according to current guidelines (Table 1) [4,6,7]. Only in a small group of diabetics at moderate risk is a target LDL range <2.6 mmol/l sufficient. If, in addition to diabetes, a manifest atherosclerotic disease is present, the risk increases to “very high” and a target LDL range <1.4 mmol/l should be aimed for. If a second vascular event occurs within 2 years on maximally tolerated statin therapy, the patient’s risk is massively increased – in this constellation, further LDL lowering to <1.0 mmol/l is recommended.

Initially up-dose statin therapy, possibly combine with ezetimibe.

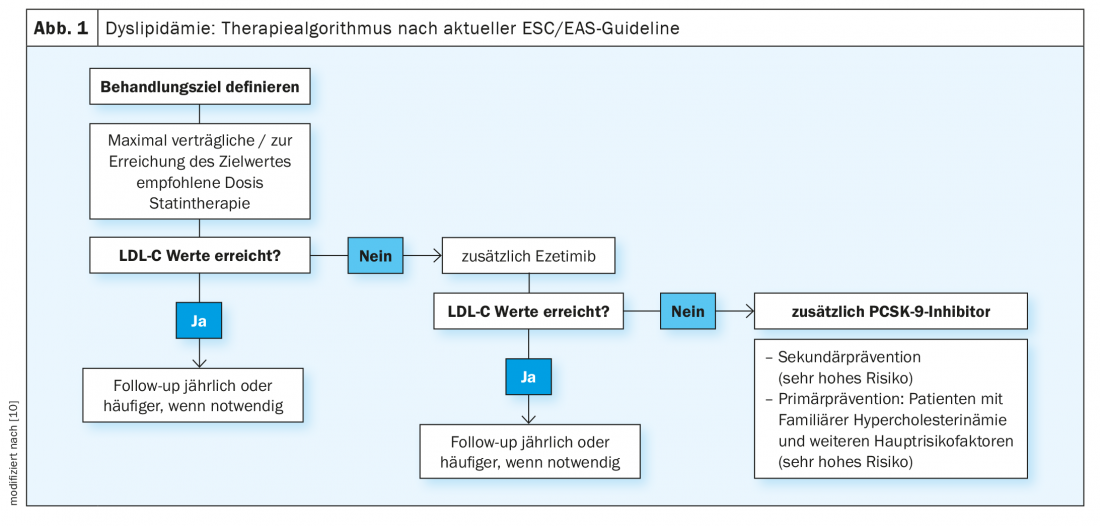

Once the therapeutic goal has been established, the first step in treatment is to determine the maximum tolerated statin dose, says Prof. Rudofsky (Fig. 1). When dosing up, on the one hand, the “rule of six” should be taken into account, which states that the greatest reduction in LDL-C can be brought about with the first initial dose and that each further doubling of the dosage leads to only 6% additional cholesterol reduction [8]. On the other hand, it must also be taken into account that a lower initial dose is associated with lower rates of side effects/statin intolerance. In a second step, the dosing out can take place. This staged approach avoids misclassifying a patient as statin intolerant, which complicates the further course of therapy. Consideration may need to be given to the use of one of the less potent statins, which are, however, often more tolerable.

If the LDL target is reached by this treatment strategy, Prof. Rudofsky recommends regular follow-ups after one year respectively depending on the clinical situation [4]. If the target range is not reached, further LDL lowering can be achieved by combination with ezetimibe, which is now also available in fixed combinations with highly potent statins. Ezetimibe attaches to the brush border of the small intestine, inhibits the transporters for cholesterol in the membrane of the mucosa cells and thus its absorption. If the transport of cholesterol from the intestine to the liver is reduced, less is also stored there and cholesterol clearance from the blood increases. For ezetimibe, the IMPROVE-IT trial is a cardiovascular endpoint study that shows statistically significant differences in the primary morbidity endpoint compared with simvastatin alone therapy [9]. Accordingly, ezetimibe has additional benefit for secondary prevention. 18,144 patients after an acute coronary syndrome with an LDL-C level of 50-125 mg/dl were randomized to 40 mg ezetimibe/simvastatin or 40 mg placebo/simvastatin. Among the 4933 diabetic patients who participated in the study, the greatest relative reductions were achieved with respect to myocardial infarction (24%) and ischemic stroke (39%) [12].

If target values are not achieved: use PCSK-9 inhibitors

As a final escalation step, PCSK-9 inhibitors are available as an “add-on,” which can achieve a further 50-60% reduction in LDL, which is a substantial effect (Fig. 1) [10]. Alirocumab and evolocumab increase the number of LDL receptors in the liver by binding to PCSK-9 and lower LDL-C in addition to statins and ezetimibe up to levels of 0.2 mmol/l. In the double-blind, multinational ODYSSEY-OUTCOMES study, the PCSK-9 inhibitor Praluent® (alirocumab) reduced death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and unstable angina by 15% and mortality alone also by 15% in high-risk cardiovascular patients within 2.8 years [11]. 18 924 High-risk patients who had experienced an acute coronary syndrome in the 12 months preceding randomization participated in the study. This was a patient collective in whom satisfactory lipid control was not achieved despite high-dose, maximally tolerated statin therapy with additional combined lipid-lowering agents in the run-in phase. Prof. Rudofsky emphasizes that the LDL value at baseline was around 1.8 mmol/l, i.e. already low, and that a further reduction could be achieved. Since patients with diabetes have an increased cardiovascular risk compared to non-diabetics, the absolute risk reduction in this subpopulation is twice as high as in patients without diabetes, says Prof. Rudofsky, adding: “The patient with type 2 diabetes benefits again to a particular extent,” whereby the therapy effect seems to be greatest in those with more pronounced vascular damage.

Source: Sanofi-Aventis

Literature:

- Dal Canto E, et al: European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 2019; 26(2), Suppl, 25-32.

- International Diabetes Federation: IDF diabetes atlas 9th edition 2019. www.diabetesatlas.org, (last accessed 10/18/2021)

- Wong K, et al: J Diabetes Complications 2012; 26: 169-174.

- The Metabolic Patient: “Fueling Knowledge,” Sanofi-Aventis AG, Web Conference, Aug. 26, 2021.

- Riesen WF, et al: Swiss Med Forum 2020; 20(0910): 140-148.

- Rudofsky G, Hellige G, Arenja N: The cardiovascular diabetic patient – an interdisciplinary challenge . HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(7): 10-16.

- Mach F, et al: Eur Heart J 2020; 41: 111-188.

- Knopp RH: N Engl J Med 1999; 431: 498-511.

- Cannon CP, et al: N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2387-2397.

- Authors/Task Force Members; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG); ESC National Cardiac Societies. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis. 2019; 290: 140-205.

- Schwartz GG, et al; N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22): 2097-2107.

- Giugliano RP, et al: Circulation 2018; 137(15): 1571-1582.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(10): 36-37