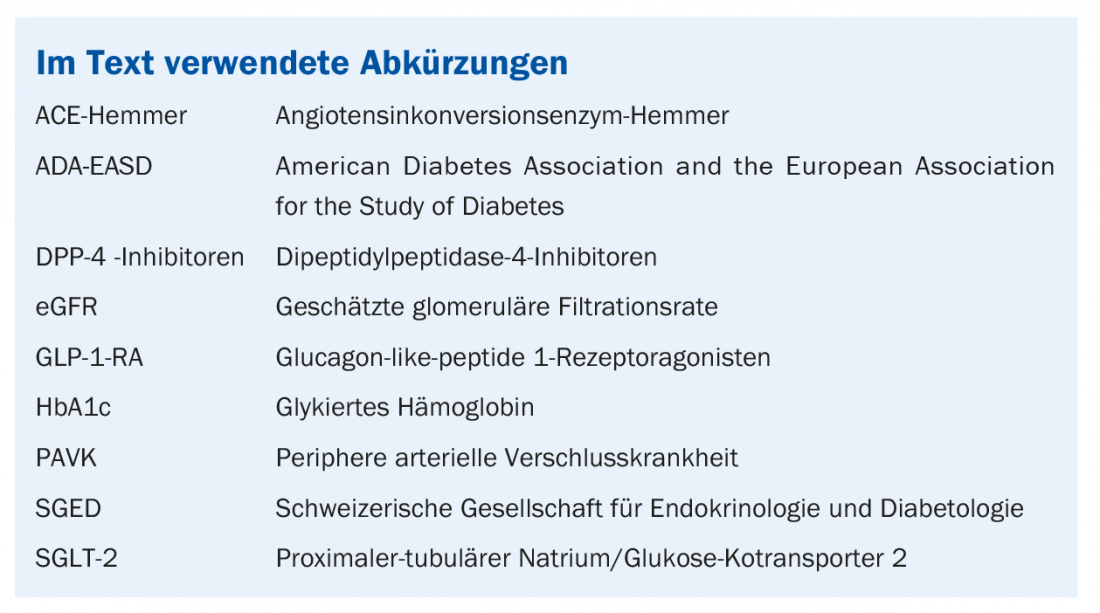

What is the benefit of new drugs of the substance classes of SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists (RA)? Which patients benefit most and in which cases are DPP-4 inhibitors or metformin indicated? Based on recent clinical trial data, the SGED recommends an adjustment of the treatment strategy and the implementation of a personalized multifactorial therapy.

The prevalence of diabetes increases with age and is highest in the over-65 age group. According to the International Diabetes Foundation (IDF), there will be approximately 438 million people with diabetes worldwide in 2030 (7.8% of the adult population) [1]. In 90% of cases it is type 2 diabetes. The number of unreported cases is high: “Around 30-40% are undiagnosed in Europe and worldwide,” says Prof. Lehmann. Early diagnosis and adequate treatment can reduce the risk of secondary diseases. Among other things, diabetes is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular sequelae. As several study findings show, the risk of myocardial infarction is several times higher in people with diabetes compared to the general population [2,3]. Cardiovascular sequelae of diabetes are associated with a higher mortality risk – “75% of all patients with type 2 diabetes die from a cardiovascular cause,” says Prof. Lehmann. Regarding the influencing factors involved, the HbA1c level shows a clear association with cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, apoplexy, PAVK, heart failure); the lower the HbA1c level, the lower the risk [4]. A target HbA1c of 6-7% helps prevent microvascular and macrovascular complications, the speaker explained.

SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1-RA offer many advantages

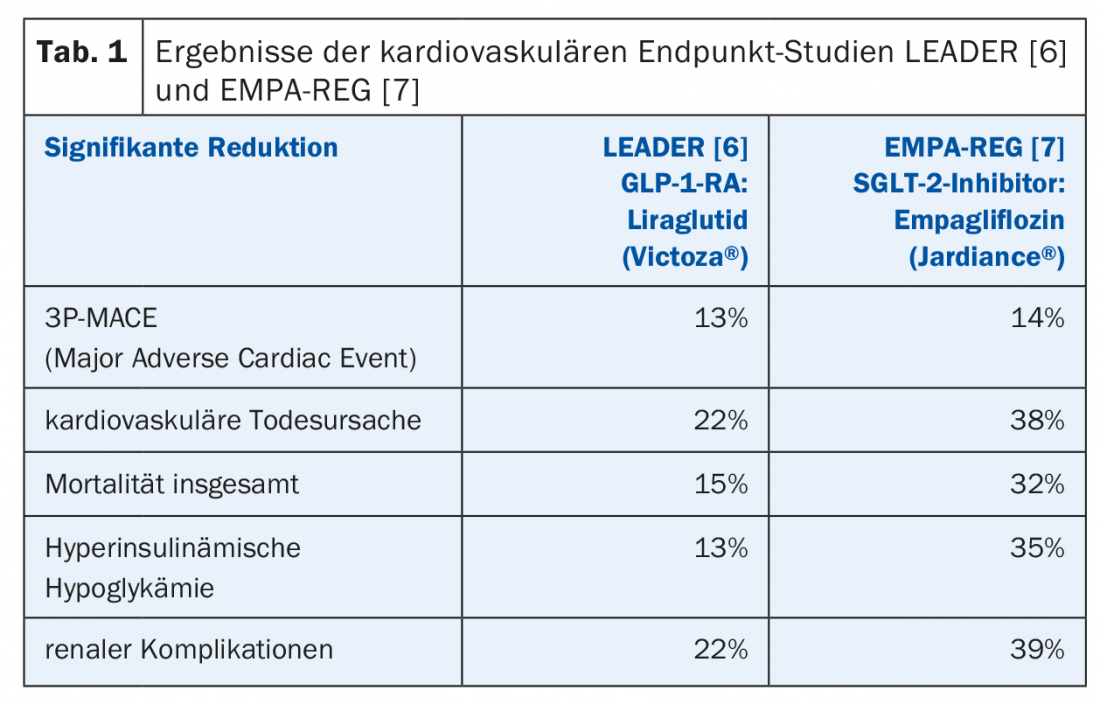

In Switzerland, there are now eight different classes of diabetes medications and six classes of insulins. The Swiss Society of Endocrinology and Diabetology (SGED) [5] has come to the conclusion that the therapeutic regimen, which has been valid since 2016, needs to be revised so that SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1-RA are given more weight. “We want a simple scheme based on patients’ key clinical characteristics and wishes,” summarizes Prof. Lehmann. A look at the studies conducted in the period 1993-2014 shows that a lot has changed. GLP-1-RA (LEADER trial) [6] and SGLT-2 inhibitors (EMPA-REG trial) [7] achieved reductions in both microvascular and macrovascular complications and mortality rates (Table 1). New study data on the SGLT-2 inhibitor dapagliflozin were presented at the 2018 American Heart Association Scientific Sessions in Chicago: The DECLARE-TIMI 58 study (n=17160) compared dapagliflozin to placebo over a five-year period for effects on cardiovascular sequelae (primary endpoints: Hospitalization for heart failure and death from cardiovascular causes). Dapagliflozin (Forxiga®) was shown to result in significant reductions in mortality and hospitalization rates due to heart failure in individuals with type 2 diabetes [8]. Among GLP-1 RAs, liraglutide Victoza® or semaglutide Ozempic®, approved in Switzerland since July 2018, have shown the most positive effects [9]. DPP-4 inhibitors are safe but have no proven cardiovascular benefit, the speaker said.

In addition to the reduction of cardiovascular complications, other criteria are of particular relevance with regard to indication according to the SGED. The following four priorities were identified as relevant to decision-making:

a) Reduction of cardiovascular complications

b) Reduction of renal insufficiency

c) Reduction of the risk of hypoglycemia

d) Application

With regard to reduction of cardiovascular risks, GLP-1-RA and SGLT-2 inhibitors have been shown to be the most effective, as mentioned above. In cases of impaired renal function, SGED recommends prescribing DPP-4 inhibitors or GLP-1-RA. If the focus is on reducing the risk of hypoglycemia, metformin or DPP-4 inhibitors can be used. In terms of weight reduction, GLP-1-RAs work better than SGLT-2 inhibitors, although unlike sulfonylureas, metformin also appears to have a beneficial effect on weight control. If cost is a priority, sulfonylureas and metformin may be used. In Switzerland, cost pressure is usually not the decision criterion, so other treatment criteria can be taken into account, the speaker said.

This reduces the number of drugs considered in the new SGED recommendations to the following four: metformin, SGLT-2 inhibitors, GLP-1-RA, and DPP-4 inhibitors.

Among SGLT-2 inhibitors, empaglifozine and Forxiga® (dapagliflozin) currently have the best evidence base. Among GLP-1 RAs, Victoza® (once daily) and Ozempic® (once weekly) performed best, and among DPP-4 inhibitors, sitagliptin performed best. Among insulins, Degludec (Tresiba®) has the best evidence, the speaker said. The revised recommendations no longer include drugs with a market share <5%: Glitazones (contraindicated in heart failure), αglucosidase inhibitors (flatulence as a side effect), glinides (must be applied several times a day).

The four clinical guiding questions of the SGED recommendations of the 2016 edition were adopted in the revised version: 1. is there an insulin deficiency?, 2. renal function: eGFR <30 ml/min?, 3. cardiovascular disease present?, 4. heart failure yes/no?

- Insulin deficiency: If insulin deficiency is present, therapy is with basal insulin; the best evidence exists for Tresiba®, which has been approved in Switzerland since 2013 – it is the only insulin that was tested in a non-inferiority study with insulin glargine with regard to cardiovascular outcome (DEVOTE study) [10]. Thereafter, Ryzodeg® (combination of Tresiba® and NovoRapid®) or a mini-base bolus system (basal insulin and GLP-1-RA) should be administered, for example in the form of Xultophy®. If the patient is recompensated and the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes is not completely certain, this can subsequently be checked again, the speaker explained.

- Impaired renal function: Regarding renal function (eGFR <30 ml/min), DPP-4 inhibitors or GLP-1-RA are indicated; if target levels are not achieved, switch to basal insulin. In the eGFR 30-60 ml/min group (25% of all patients with diabetes), nephroprotection can be achieved by SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1-RA. In impaired renal function, metformin must be reduced and should be taken at an estimated glomerular filtration rate eGFR <30 ml/min should no longer be used. If renal function values are in the range eGFR 30-45 ml/min, the dosage of metformin should be reduced by half. With the exception of linagliptin, most DPP-4 inhibitors must be reduced. If the target values are not reached, the patient is switched to an insulin with the lowest possible risk of hypoglycemia (new long-acting insulins such as Tresiba®). SGLT-2 inhibitors are no longer effective in lowering HbA1c below 45 ml/min, which is the lower limit defined in the Compendium for the use of this class of agents.

- Cardiovascular disease: in the presence of cardiovascular disease, SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1-RA are also preferable in addition to metformin. The best evidence is for empagliflozin (Jardiance®) for SGLT-2 inhibitors and liraglutide (Victoza® semaglutide) for GLP-1 RA. For BMI >28, GLP-1 RA should be used. In the absence of cardiovascular disease, DPP-4 inhibitors can also be used. The speaker pointed out that peripheral arterial disease (PAVD) is a cardiovascular disease that is often not properly diagnosed. “About 25% of all patients have symptomatic cardiovascular disease and about 50% have asymptomatic disease,” he said.

- Heart failure: in the presence of heart failure, SGLT-2 inhibitors are clearly preferred, regardless of whether the patient already has heart failure or whether one is treating preventively. According to the speaker, there are studies showing that diabetes-associated cardiomyopathy is detectable in more than two-thirds of diabetic patients without heart failure. 25% of all patients with diabetes without known heart failure have heart failure on cardiac ultrasound, two-thirds of whom have diastolic heart failure.

Conclusion

“The new drugs have shown that microvascular complications, especially renal complications, were reduced, but that macrovascular and heart failure were also very positively affected,” summarizes Prof. Lehmann. In view of the latest scientific findings, the question arises whether it is not possible to restrict oneself to the two drug classes GLP-1-RA and SGLT-2 inhibitors if there is no insulin deficiency. The 2018 ADA-EASD suggest limiting to GLP-1-RA and SGLT-2 inhibitors, guided by the following two guiding questions: 1. does the patient have a cardiovascular disease?., 2. does the patient have chronic kidney disease? If the former, GLP-1 RA should be preferred (alternative: SGLT-2 inhibitors). If the latter, SGLT-2 inhibitors should be considered the first choice (alternative: GLP-1-RA).

Contradictory to current knowledge is the current low market share of GLP-1-RA and SGLT-2 inhibitors. In this context, the removal of barriers among physicians is an issue; treatment strategies that are no longer up-to-date should be revised and adapted. In addition, the cost coverage of the new diabetes medications by health insurance is not yet guaranteed in Switzerland.

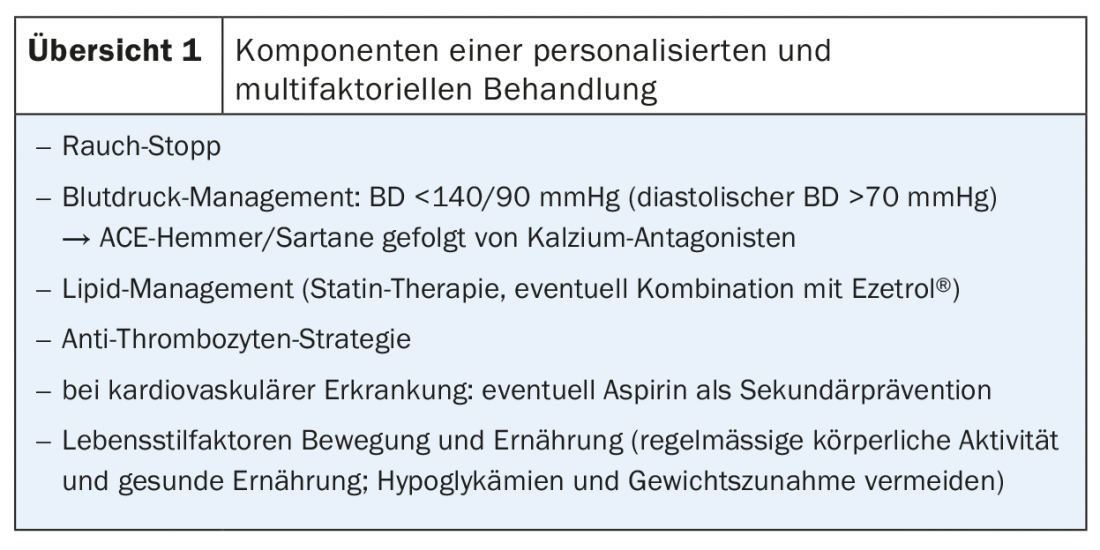

According to the SGED, in addition to SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1-RA, metformin and DPP-4 inhibitors can also be used, whereby the decision for the appropriate preparation should be individualized (with reference to the stated decision criteria of the SGED recommendations). Personalized and multifactorial therapy has been shown to be most promising (review 1). Patient involvement in determining the treatment strategy should be an important principle of therapy.

That early diagnosis and adequate treatment reduces the mortality risk of people with diabetes is confirmed by a Danish study. Consequently, patients with individualized multifactorial therapy have a comparable life expectancy to persons without diabetes [11,12].

Source: FOMF Diabetes Update Refresher, November 15-17, 2018, Zurich.

Literature:

- International Diabetes Foundation (IDF): Diabetes Atlas 2009,4th edition, www.diabetesatlas.org/resources/previous-editions.html, last accessed 05 Jan. 2019.

- Gregg EW, et al: Changes in diabetes-related complications in the United States, 1990-2010. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(16): 1514-1523.

- Haffner SM, et al: Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1998; 339(4): 229-334.

- Stratton IM, et al: Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000; 321(7258): 405-412.

- Swiss Society of Endocrinology and Diabetology (SGED), www.sgedssed.ch, last accessed 05 Jan 2019.

- Marso SP, et al: LEADER Trial: liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 311-322.

- Zinman B, et al: Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2117-2128.

- Wiviott SD: Dapaglifozin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2018 Nov 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa 1812389 [Epub ahead of print].

- Swissmedic, www.swissmedic.ch, last accessed 05 Jan. 2019.

- Marso SP, et al: DEVOTE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of degludec versus glargine in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 723-732.

- Griffin SJ, et al: Effect of early intensive multifactorial therapy on 5-year cardiovascular outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes detected by screening (ADDITION-Europe): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2011; 378: 156-167.

- Carstensen B, et al: The Danish National Diabetes Register: trends in incidence, prevalence and mortality. Diabetologia 2008; 51: 2187-2196.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(1): 38-40