Eradication, in the case of infectious diseases, means achieving an incidence of zero. This article addresses the question of whether eradication by vaccination is a utopia or an eutopia, and which factors relevant to practice must be considered in the daily routine of family physicians in order to achieve this goal.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has ambitious goals. Various infectious diseases are to be eradicated worldwide. Eradication means a global incidence of zero. If successful, prevention and control measures are suspended. Elimination is the first important step towards eradication. An incidence of zero is achieved regionally. Prevention and control continue to be of great importance here, as it is essential to prevent the recurrence of the diseases. For most infectious diseases, we are at the control stage. Specific measures help to reduce incidence, prevalence, morbidity and mortality.

Several conditions should be met for successful eradication:

- High infectivity of the pathogen and restriction to humans as the only pathogen reservoir are important.

- Inducible immunity and the ability to make a definitive diagnosis are critical.

- An effective intervention, for example in the form of an effective vaccination, must be available.

- It is helpful if elimination has already been achieved.

- Only diseases that play a major role in global health policy are suitable.

Eradication of smallpox – a success story

Despite years of effort with enormous financial and human resources in various official WHO eradication programs (e.g., malaria since 1955, poliomyelitis since 1988), eradication has so far succeeded only for smallpox – a success story in medicine.

The first evidence of smallpox disease can be found very early in history. Typical skin lesions were found, among others, on the mummy of the Egyptian King Ramses (1156 BC). It was a dangerous disease with a lethality rate of 20-60%, in infants even up to 95%. Due to the observation that the survivors of the disease did not get sick a second time and in turn were able to take care of sick people, the technique of so-called inoculation or variolation was already used in the 18th century. Material was taken from a fresh smallpox pustule and inserted directly subcutaneously into a healthy person with a lancet. Only 2-3% of variolated individuals suffered lethal smallpox disease. The others remained healthy or showed significantly less severe courses.

Despite critical voices, the practice of variolation quickly gained acceptance and was regularly used in all social classes, for example also in European aristocratic circles. The English scientist Edward Jenner (1749-1823), himself variolated at the age of eight without complications, finally made an interesting observation: cowpox sufferers who had gone through the harmless process of cowpox did not later contract smallpox again. In a first experiment in 1796, he took material from a cowpox skin lesion on the hand of a cowgirl and inoculated it into an eight-year-old boy. Despite repeated direct contacts with smallpox patients, the boy remained healthy. Derived from “vacca”, Latin for cow, the term “vaccination” was thus created. This new method quickly spread and was soon used worldwide with great success.

Effective implementation of hygiene measures has further suppressed the disease thanks to better understanding. In 1967, WHO launched a global campaign to eradicate smallpox. Just ten years later, this goal was achieved. Thus, on May 8, 1980, the world was officially declared smallpox-free and all vaccination programs were halted.

Polio control

The fight against polio and especially measles, on the other hand, is not a success story. Polio was eliminated in America in the early 1980s. In a 1988 resolution, the WHO had then provided for eradication by the year 2000. Most countries achieved interruption of viral transmission and thus regional elimination within two to three years through large-scale vaccination campaigns and sanitation measures. Already in 2000, a 99% reduction in polio incidence was recorded. A major step towards eradication was thus taken. However, to date, polio remains endemic in four countries worldwide – namely India, Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Poliovirus is a member of the enterovirus family and is transmitted fecal-orally. Only 1% of polio infections progress as paralytic polio; the remainder present with a mild, nonspecific clinic. This makes it difficult to make a reliable diagnosis. Regional outbreaks with occurrence of paralytic polio in non-immune individuals occur repeatedly due to “export” of polioviruses to polio-free regions.

The main difficulties in the definitive eradication of polio are social and geopolitical. In large parts of Nigeria, for example, the rumor that polio vaccination causes infertility in girls has persisted for years. As a result, vaccination programs in certain states were stopped completely. Time and again, health workers are attacked and terrorized during vaccination efforts. Many areas in Afghanistan, on the other hand, were simply inaccessible to vaccination programs due to political instability and active conflict. Further, oral polio vaccination was found to be ineffective, particularly in India. This is likely contributed by a high prevalence of diarrheal disease, including non-polio enteroviruses. Despite all obstacles, efforts continue to achieve polio eradication as soon as possible.

Problem case measles – also in Switzerland

The biggest problem is measles. Worldwide, the disease remains one of the top five causes of death in young children despite highly effective vaccination. Overall, the infection is fatal in one in 1000 cases, even in the privileged “non-developing” countries. Neurological damage remains with the same frequency. In North and South America, measles has been eliminated since 2003. Unfortunately, however, regional outbreaks of disease occur there as well. This is due to imported cases from areas with persistent virus transmission, such as Switzerland!

A 95% vaccination coverage rate is needed to sustainably stop measles transmission. In Switzerland, this currently averages 82%. There are major regional differences in this respect. In some cases, vaccination coverage rates can be compared with countries such as Indonesia, Pakistan and Burma. One of the main reasons is the fact that measles is not perceived as a dangerous disease and therefore people deliberately avoid vaccination. Also, dubious untruths persistently circulate. For example, the accusation that the disease measles causes autism has been refuted several times in scientific studies, but nevertheless continues to be circulated.

To support the WHO goal of measles elimination in Europe by 2015 and also to efficiently protect the population of Switzerland from this dangerous disease, the Federal Office of Public Health launched a national measles elimination strategy in 2011. One of the main focuses of the strategy is to revaccinate all non-immune individuals born 1964 and younger. Every doctor consultation of a person in this age group should be used to check the vaccination card and catch up on missing vaccinations. To improve the uptake of measles vaccination, vaccination with a maximum of two doses of MMR vaccine will be exempt from the deductible (consultation, vaccine and injection) until the end of 2015.

Vaccination recommendation for pertussis

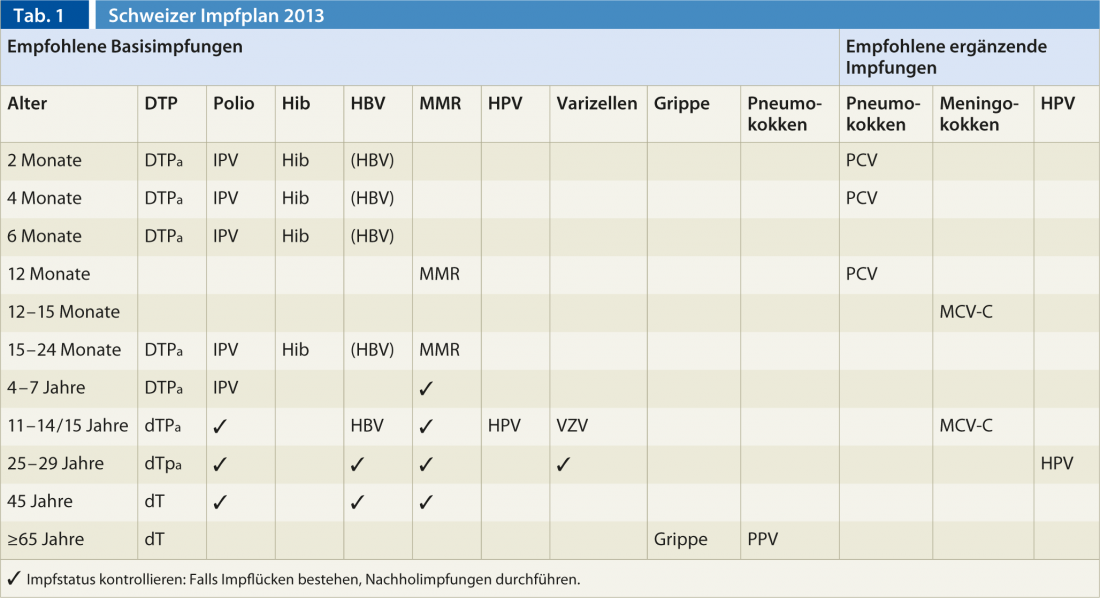

The current Swiss vaccination schedule 2013 (Tab. 1) focuses on another important disease, pertussis. In Switzerland, the incidence has increased significantly in recent years. Around 7400 cases occurred in 2012, almost twice as many as in the previous year. The most severe disease is contracted by small infants under six months of age. Pertussis infection is fatal in one in 100 cases in this age group. The vaccination recommendation for pertussis was therefore adjusted accordingly. Specifically, additional vaccination is recommended in adolescence as well as young adulthood. Adolescents and adults between the ages of 25 and 29 should be vaccinated against pertussis as part of the dT booster vaccination. Regardless of age, pertussis vaccination is recommended for all persons who have private or professional contact with small infants. In addition, pregnant women in the 2. or 3rd trimester receive pertussis vaccination. For infants attending a care facility (e.g., daycare center, daycare provider) before five months of age, an accelerated vaccination schedule of one dose each at two, three, and four months of age is used. This allows a good protection against pertussis to be built up as quickly as possible.

Conclusion for practice

- Eradication by vaccination is not a utopia, shown by the example of smallpox.

- Barriers to eradication programs are multiple, complex, and mostly disconnected from medical facts.

- Elimination is the first important step towards eradication.

- Elimination can also become eutopia in Switzerland: inform, vaccinate (MMR vaccination exempt from deductible until end of 2015)!

- Extension of pertussis vaccination recommendation with revaccination in adolescence and adulthood to protect infants: remember, inform, vaccinate with dT vaccination!

Anita Niederer-Loher, MD

Literature:

- www.infovac.ch

- www.bag.admin.ch

- Hopkins DR: Disease Eradication, N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 54-63 [PMID: 23281976].

- Riedel S: Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination, Proceedings (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2005; 18(1): 21-25 [PMID: 16200144].

- Aylward B, Tangermann R: The global polio eradication initiative: lessons learned and prospects for success, Vaccine 2011; Dec 30; 29 Suppl 4: D80-5 [PMID: 22486981].

- Moss WJ, Griffin DE: Measles. Lancet 2012; Jan 14; 379(9811): 153-164 [PMID: 21855993].