Venous diseases are not only cosmetically disturbing, but in severe cases can lead to disability. The CEAP classification has become widely accepted for the classification of chronic venous disease. Today, a whole range of methods are available for therapy: Endovenous thermal ablation, sclerotherapy and vein surgery are firmly established, but several other promising procedures are entering the market.

Venous disease is one of the most common conditions in the general population. Over 90% of individuals have some form of visible venous changes [1]. The spectrum ranges from the purely cosmetically disturbing spider vein varicosis (59%) to the invalidating leg ulcer (0.1%). Most people with varicosis have no symptoms, but some complain of tired legs, feelings of heaviness and pressure, pain, pruritus, and leg cramps to skin lesions, stasis dermatitis, and ulceration [2]. In addition, 26% of patients with varicose veins suffer from depression at the same time, and in patients with venous leg ulcers the figure is as high as 40-60% [3]. Depression itself is associated with a 1.6-fold increased risk of venous thromboembolism [4].

Diagnostics

Duplex sonography is the gold standard for evaluating varicose leg disease. Whether additional imaging such as MR phlebography is necessary depends on the extent of variceal disease. Hemodynamic measurement is also useful and recommended by the American Venous Forum Guidelines.

Classification of chronic venous disease

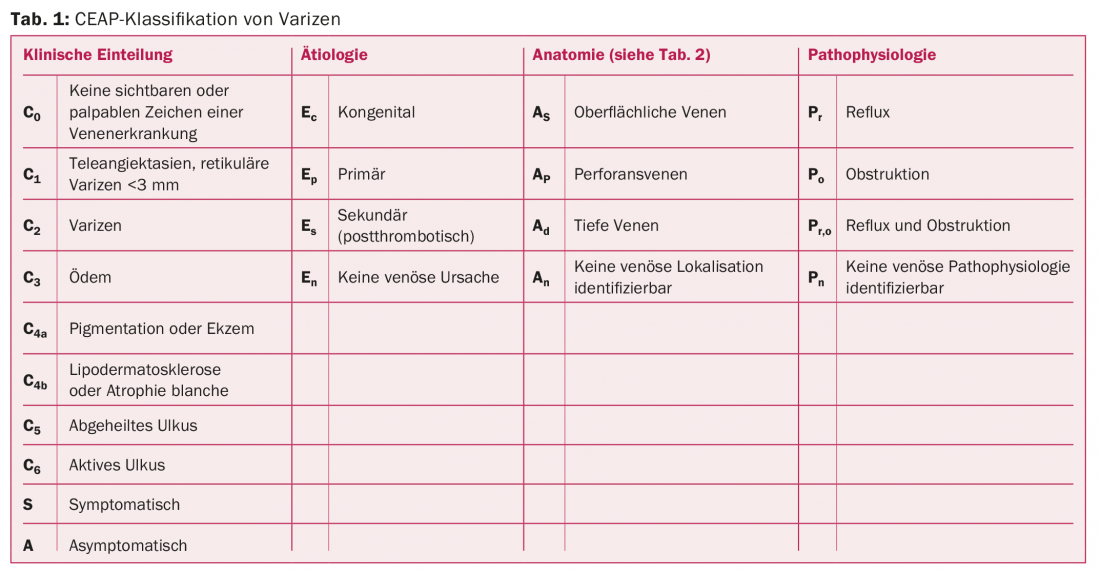

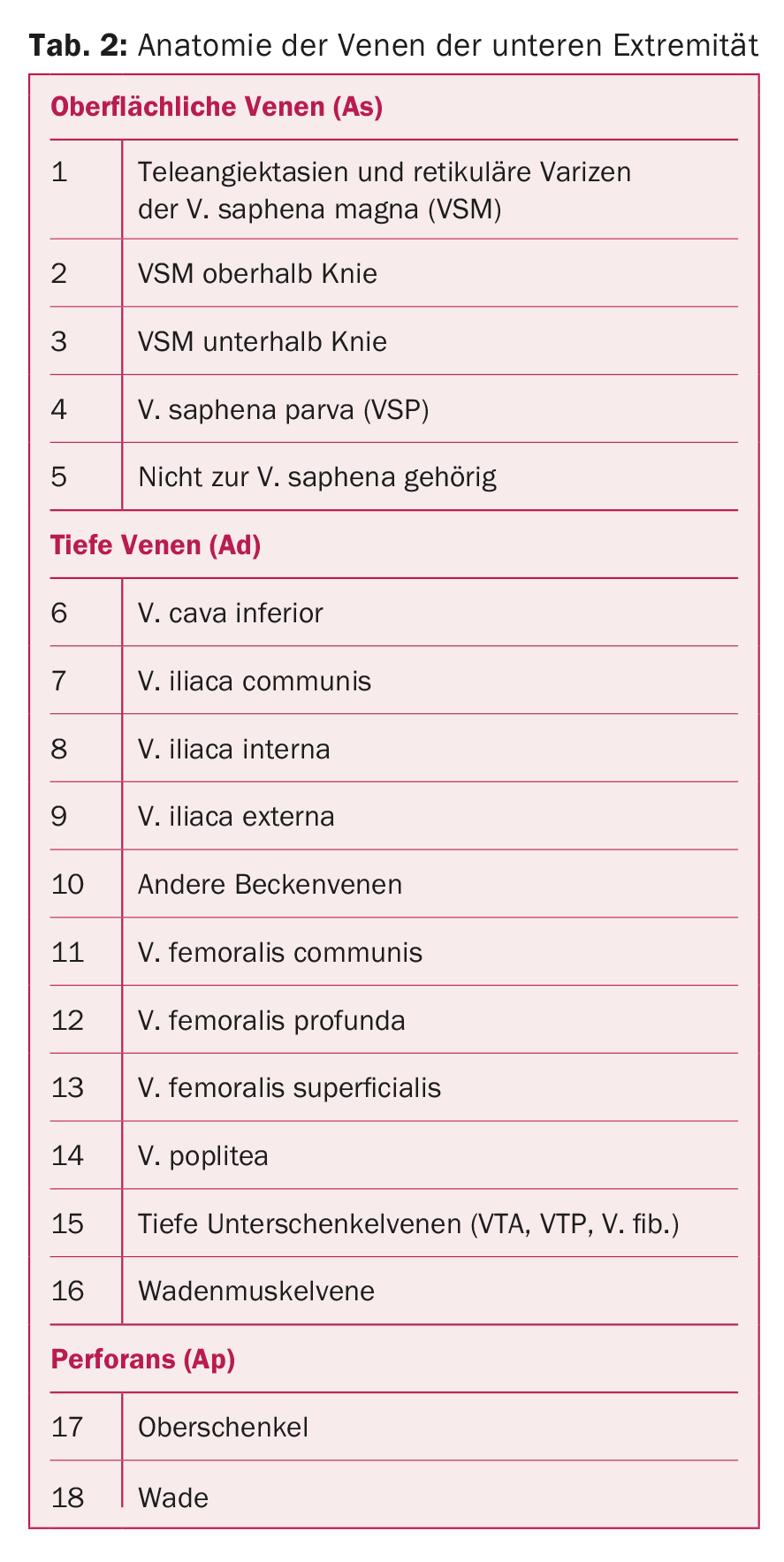

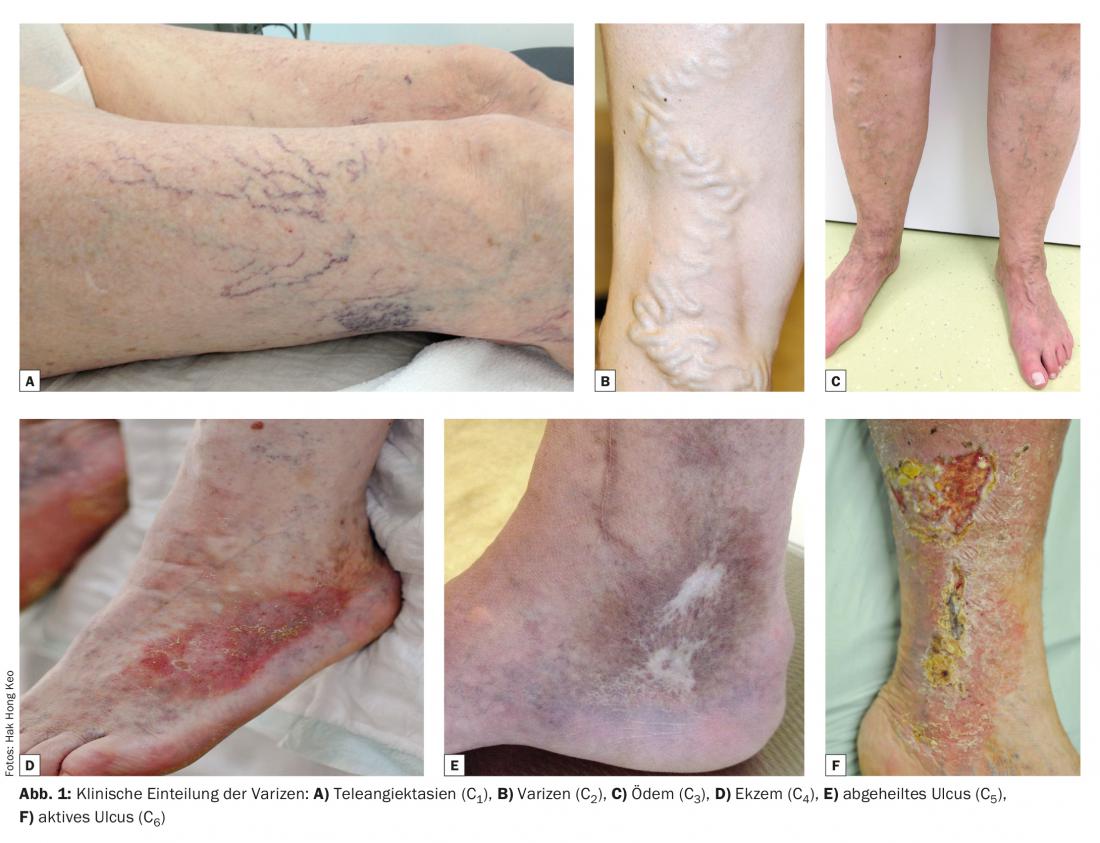

Internationally, the CEAP classification has become accepted for describing chronic venous disease(Clinic, Etiology, Anatomy, Pathophysiology) (Tables 1 and 2) .

Figure 1 shows the different manifestations of venous disease according to the clinical classification. If left untreated, clinically significant varicosis often leads to complications such as chronic edema, trophic skin changes, eczema, leg ulcers, deep vein insufficiency, and varicophlebitis; deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism rarely occur.

When to refer to angiologist resp. Vascular surgeons?

- All patients with at least one of the following should be presented to a vascular specialist:

- Patients with symptomatic primary varicosis (C2,C3).

- Patients with symptomatic recurrent varicose veins

- Patients with skin lesions, such as pigmentation, eczema, atrophie blanche, lipodermatosclerosis (C4a, C4b).

- Patients with varicophlebitis or phlebitis of the superficial veins

- Healed venous leg ulcer (C5)

- Patients with an active venous leg ulcer that does not heal within two weeks (C6).

Endovenous thermal ablation

Endovenous thermal ablation is becoming increasingly popular. The method is minimally invasive, can be performed on an outpatient basis and has a low complication rate. The physician uses ultrasound guidance to puncture the diseased vein at the lowest point, usually infragenual or malleolar. A laser probe is then inserted to the uppermost insufficiency point of the varicose vein. The puncture is usually the only entry point needed, so no scar is left behind. To ensure that the procedure is painless, tumescent anesthesia is used. With the help of the probe, the doctor triggers laser impulses that close the pathologically dilated vein from the inside. As a result, the vein dies and is gradually broken down by the body. Throughout the treatment, the patient remains fully mobile and usually able to work.

Since the first publication on endovenous thermal ablation in 2001, the number of data has steadily increased. A 2009 meta-analysis of 12,320 treated legs showed a success rate of 84% for radiofrequency and 94% for laser therapy after three years of follow-up [5]. The latter is significantly more effective than varicose vein surgery (78%). A recently published meta-analysis of 28 randomized trials found no difference in recurrence rates between endovenous thermal ablation and varicose vein surgery. However, the former showed a lower wound infection rate and hematoma formation. The convalescence time is also five days shorter than with surgery [6].

Sclerotherapy

Sclerotherapy has been used for decades to treat varicose veins. In recent years, many studies, some of them randomized, have been published on the efficacy and safety of the method [7,8]. Sclerotherapy, when used correctly, is described as a safe and effective method. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism as side effects are rare [9].

Endovenous mechanochemical ablation (Clarivein®)

Endovenous mechanochemical ablation (Clarivein®) of the insufficient truncal veins combines mechanical and chemical ablation to close the truncal veins. Here, tumescent anesthesia of the tissue is completely dispensed with. In the Clarivein procedure, a propeller at the tip of the catheter is activated and the sclerosing agent (usually sodium tetradecyl sulfate or polidocanol) is injected simultaneously with slow retraction. The rotation of the propeller causes damage to the intima and venospasm. The sclerosing agent injected at the same time leads to complete occlusion of the truncal vein.

In a prospective study of 29 patients with v. saphena magna insufficiency, the Clarivein method was shown to have a primary occlusion rate of 97% after six months of follow-up, demonstrating a success rate comparable to endovenous thermal ablation [10]. The closure rate after two years of follow-up was very high at 96%. The Clarivein method is a promising therapeutic option. However, randomized trials and long-term safety and efficacy results are currently lacking.

VenaSeal Sapheon® closure

A newer procedure that also does not use tumescent anesthesia is the VenaSeal Sapheon® Closure system. Here, an acrylic adhesive (n-butyl cyanoacrylate) is used to close the truncal vein. The first feasibility study by Almeida et al. in 38 patients with stage C2-3 V. saphenous insufficiency showed a primary occlusion rate of 92% after one year with significant improvement of the VCSS score [11]. All procedures were described as complication-free and painless. However, further studies and long-term results are needed to prove the safety and efficacy of this procedure.

Steam ablation

In order to develop an even safer and simpler method of treating varicosity, intensive research has been conducted on steam ablation in recent years. Van den Bos et al. were able to show in a proof-of-principle study that steam ablation of the great saphenous vein as well as the saphenous parva vein was effective in 19 patients. [12]. In a larger work with 75 patients in clinical stage C2-5 with 88 cases of V. saphena magna insufficiency, a primary occlusion rate of 96% at six and twelve months was achieved [13]. The technique and setting for steam ablation are similar to endovenous thermal ablation. Tumescent anesthesia is still necessary, and compression for one week after ablation is recommended. Further safety and efficacy studies are needed before this method can be included in the routine treatment of varicosity.

Which therapy should be chosen?

In summary, the treatment options for symptomatic varicosity have expanded significantly in recent years, making it possible to offer each patient an optimal individual solution. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend endovenous thermal ablation primarily and ultrasound-targeted sclerotherapy secondarily if thermal ablation is not feasible [14]. Varicose vein surgery is only considered as a last option. Compression therapy is no longer recommended as the first choice because it is associated with poor compliance. Despite these recommendations, varicose vein surgery still has its place, especially in extensive, large-caliber, and tortuous varices, where thermal ablation and sclerotherapy have their limitations.

Conclusion for practice

- Venous disease is a common problem in practice.

- Patients with clinical stage C2 varices with symptoms and stage C3 and higher varices should be referred to a vascular specialist.

- The gold standard of variceal diagnosis is duplex sonography.

- Treatment options for varicose veins have expanded and allow for an optimal, individualized solution for each patient.

Literature:

- Rabe E, et al: [Bonn Vein Study of the German Society of Phlebology. Epidemiological study on the question of the frequency and severity of chronic venous disease in the urban and rural resident population]. Phlebology 2003; 32: 1-14.

- Rabe E, et al: Treatment of chronic venous disease with flavonoids: recommendations for treatment and further studies. Phlebology 2013; 28: 308-319.

- Sritharan K, et al: The burden of depression in patients with symptomatic varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2012; 43: 480-484.

- Enga KF, et al: Emotional states and future risk of venous thromboembolism: the Tromso Study. Thromb Haemost 2012; 107: 485-493.

- van den Bos R, et al: Endovenous therapies of lower extremity varicosities: a meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg 2009; 49: 230-239.

- Siribumrungwong B, et al: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials comparing endovenous ablation and surgical intervention in patients with varicose vein. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2012; 44: 214-223.

- Rabe E, et al: European guidelines for sclerotherapy in chronic venous disorders. Phlebology 2013; 29(6): 338-354.

- Rathbun S, et al: Performance of endovenous foam sclerotherapy in the USA for the treatment of venous disorders: ACP/SVM/AVF/SIR quality improvement guidelines. Phlebology 2013; 29(2): 76-82.

- Gillet JL, et al: Side-effects and complications of foam sclerotherapy of the great and small saphenous veins: a controlled multicentre prospective study including 1,025 patients. Phlebology 2009; 24: 131-138.

- Elias S, et al: Mechanochemical tumescentless endovenous ablation: final results of the initial clinical trial. Phlebology 2012; 27: 67-72.

- Almeida JI, et al: First human use of cyanoacrylate adhesive for treatment of saphenous vein incompetence. J Vasc Surg: Venous and Lym Dis 2013; 1: 174-180.

- van den Bos RR, et al: Proof-of-principle study of steam ablation as novel thermal therapy for saphenous varicose veins. J Vasc Surg 2011; 53: 181-186.

- Milleret R, et al: Great saphenous vein ablation with steam injection: results of a multicentre study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2013; 45: 391-396.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG168/NICEGuidance/pdf/English

CARDIOVASC 2015; 14(2): 15-18