The total number of violent crimes related to domestic violence (HG) has been steadily increasing in Switzerland since 2011. On average, one person dies every two weeks in Switzerland due to domestic violence. This is despite the fact that preventive multimodal approaches to combating HG exist at both the federal and cantonal levels. Only about 24% of those affected share their experiences of violence with their doctor.

The total number of violent crimes related to domestic violence (HG) has been steadily increasing in Switzerland since 2011. On average, one person dies every two weeks in Switzerland due to domestic violence. This is despite the fact that preventive multimodal approaches to combating HG exist at both the federal and cantonal levels. Only about 24% of those affected share their experiences of violence with their doctor. Figures on doctor-patient contacts in the context of HG are collected irregularly in Switzerland. The last major healthcare survey showed that just over 80% of physicians had cared for at least one person affected by HG in the past year. From a medical point of view, the care of patients is often limited to the treatment of minor injuries (bruises/hematomas/crush-crack wounds) and is therefore not per se an indication for emergency medical presentation. Nevertheless, those affected find themselves in a personal predicament. It is therefore advisable to provide support as soon as possible (documentation of injuries, clarification of child protection, information on victim assistance). Likewise, safety issues must be clarified with regard to both the person concerned and any children living in the family. In addition, victims of violence are more receptive to possible external intervention shortly after the assault. HG rarely ends spontaneously or after an initial intervention. This should not stop us from always offering help without prejudice. This in the hope that the day has come when the step out of the spiral of violence will be successful.

Definition and numbers

On April 1, 2018, the Istanbul Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence entered into force in Switzerland. It is a comprehensive, international convention of the Council of Europe aimed at combating human rights violations of this kind. According to Art. 3 para. 1 lit. b of the Istanbul Convention, domestic violence is defined as “[…] all acts of physical, sexual, psychological or economic violence occurring within the family or household or between former or current spouses or partners, whether or not the perpetrator has or has had the same residence as the victim” [1].

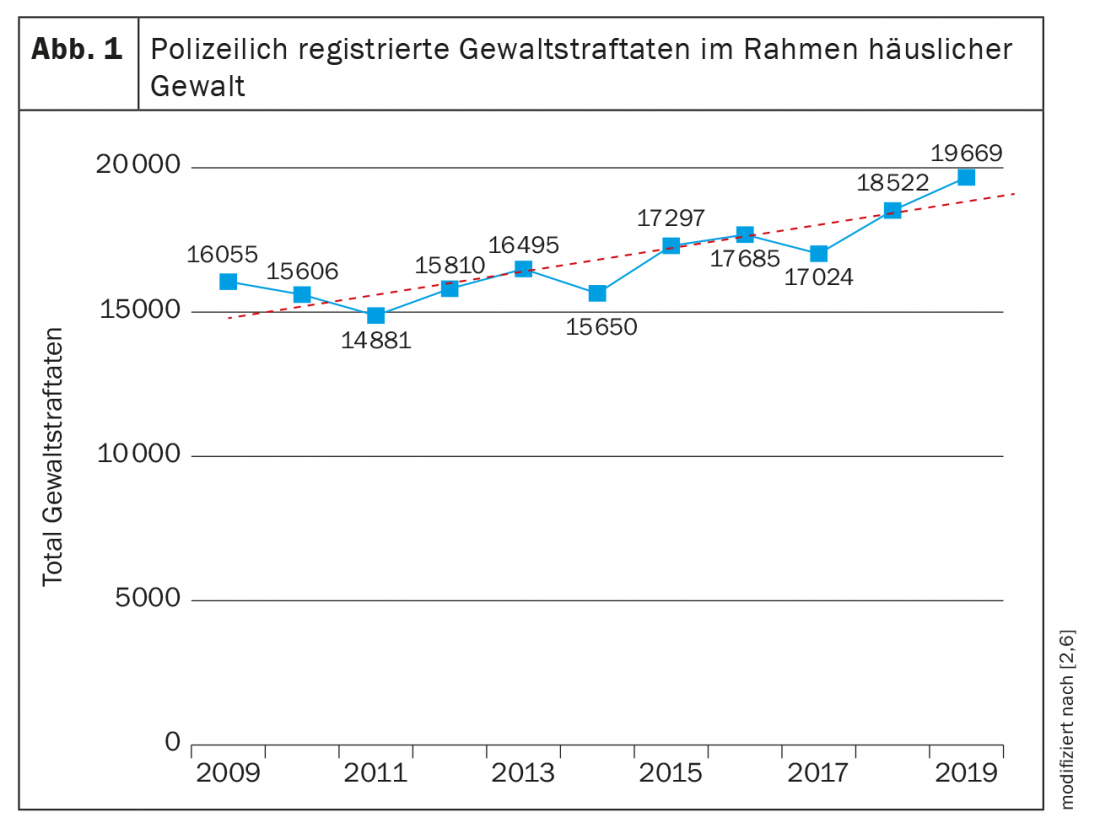

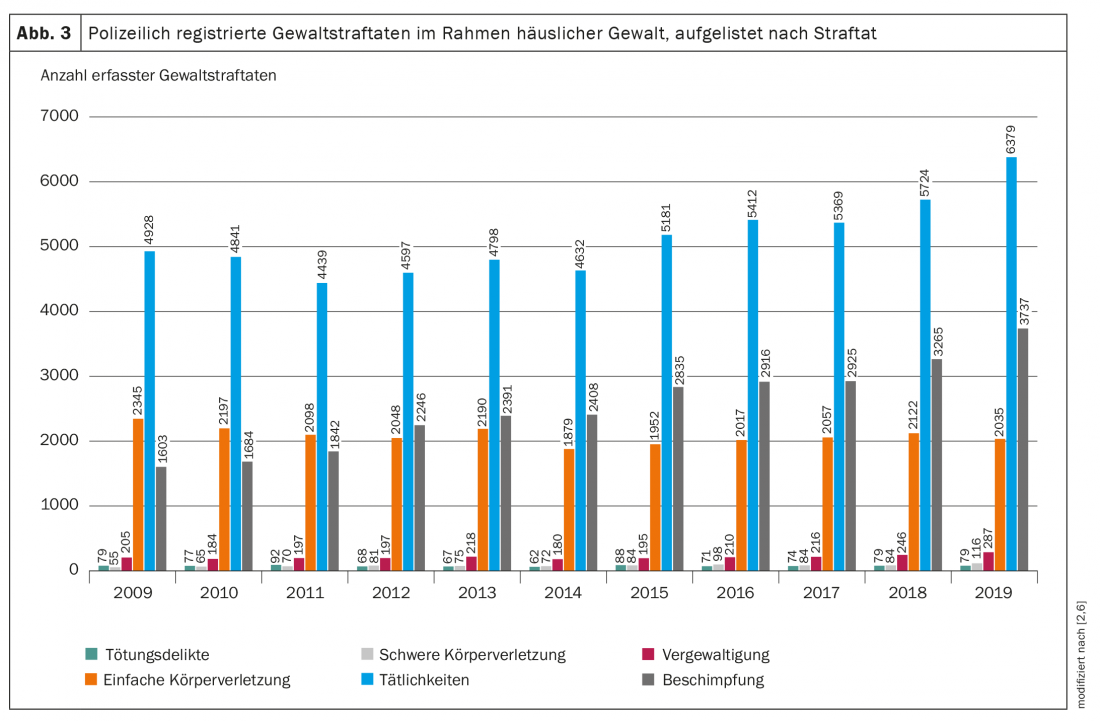

Regularly published figures on HG exist in Switzerland from the police crime statistics PKS as well as the victim assistance statistics. The PKS in particular is regularly used to assess the development of HG. The PKS shows the bright field of HGs known to the police. The PKS does not list the individual cases of HG here, but the number of criminal offenses that arise in the context of HG. Theoretically, several offenses can be recorded per case (e.g., simple assault and threat). Since 2011, the numbers of violent offenses in the context of HG according to PKS in Switzerland have been on the rise (Fig. 1) [2,6]. The development in the individual cantons can be seen in the PKS of the respective cantons. The first primary care physician survey on HG dates to 2006, with an incidence of 0.25 cases per 1000 physician-patient contacts. Other, national systematic surveys are scarce. The most recent and arguably most comprehensive survey is from 2019. In it, more than 80% of somatic physicians reported that they had knowingly treated at least one person for HG in the past year [3]. The University Emergency Center Inselspital Bern UNZ retrospectively recorded all those affected by HG over 11 years. This resulted in a prevalence of 0.09% [4]. A victim assistance survey by Killias et al. found that only about 24% of people affected by violence turn to a health care professional with their experiences [5]. This shows that physicians are regularly confronted with victims of violence, but that there is still a large dark field.

Injury patterns

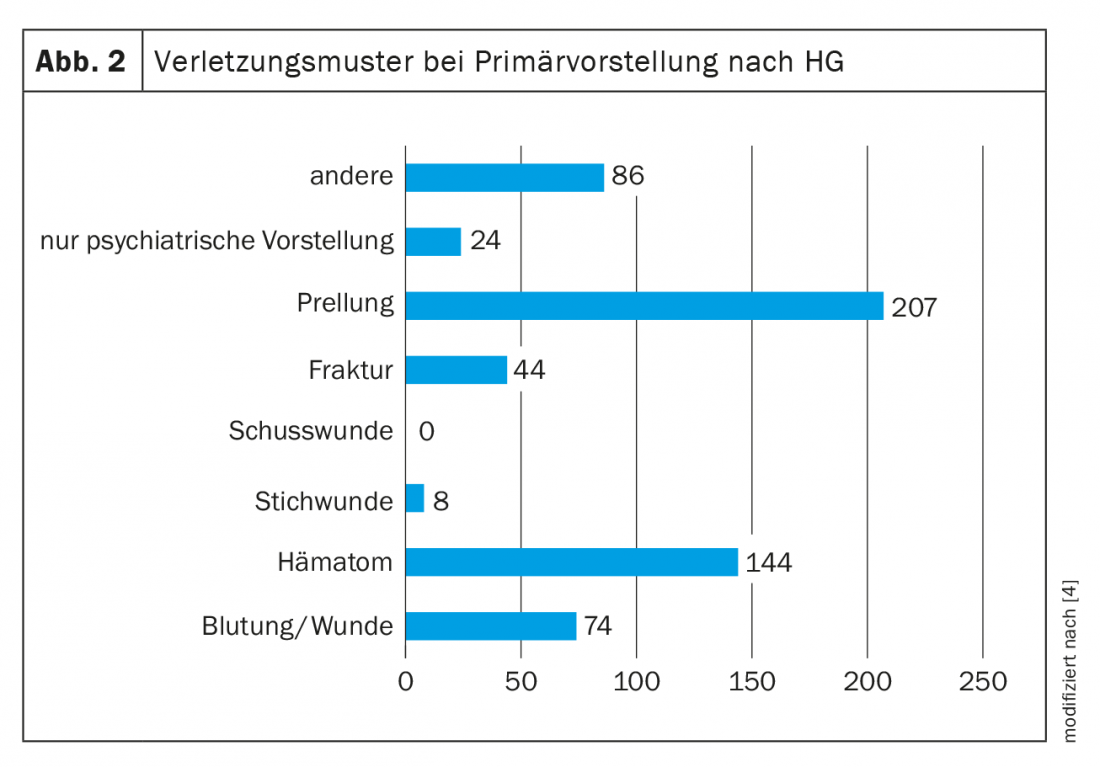

According to the study by Hostettler-Blunier et al. most of those affected have minor injuries in the form of hematomas, bruises and bleeding wounds (Fig. 2). These are caused by blows with the open hand or fist and by kicks. The most frequent localizations were the head, arms, followed by the neck, legs as well as thorax. 16% of those affected reported being strangled. No clinical radiological evidence of post-strangulation injuries was found in any individual [4]. These medical data with recording of minor injuries coincide with the crimes recorded in the PKS. Broken down into the various criminal offenses, there are high percentages for “Art. 180 Threat” and “Art. 126 Assault”, as well as for “Art. 123 StGB Simple bodily harm” and “Art. 177 StGB Insult”. Serious crimes are rare in comparison (Fig. 3) [2,6].

In cases in which violence is not reported directly by the victim or a third party, contradictory and implausible information about the history of the injury, for example, as well as numerous injuries of different ages, at best shaped (e.g., double contour of hematomas in the case of cane blows), and located in areas of the body that are not typical for falls, may indicate that the injury was caused by a third party.

Care for victims of domestic violence

Regarding the treatment of victims of domestic violence, we recommend a standardized approach, for example, following the WHO recommendation using the acronym S.I.G.N.A.L. [7]. S. I. stand for Signal/Interview. As a first step in doctor-patient care, the suspicion of HG should be addressed openly. Here, it is important to receive and document the information openly and non-judgmentally. A review of the facts is the responsibility of the law enforcement agency. The G. N. are the abbreviations for the “thorough examination” as well as “noting”. Both old and new injuries should be documented, using a standardized documentation sheet whenever possible. In the case of serious injuries, forensic medicine must be consulted. Under A. clarifications in the sense of further medically indicated clarifications as well as clarifications for the safety of the persons concerned, including children, are carried out. A personal safety plan should be discussed with those involved or at least handed in*. The L. finally means the delivery as well as explanation of guidelines, which can be obtained from the responsible cantonal offices. Due to the above-mentioned injury patterns, the purely somatic care of injuries is often limited to appropriate diagnostics with subsequent extended analgesia, possibly paired with wound care. Affected persons are to be written incapable of work if desired, especially in the case of hematomas in the facial area and work in public. Always evaluate tetanus booster vaccination and PEP for injuries. Sexual offenses should be assigned to a specialized agency. Good practice templates on documentation forms as well as possible concepts for the care of affected HG are described in the final report to the Federal Council on medical care for affected HG by Krüger et al. to be taken from [3].

* Possible template at www.big.sid.be.ch/de/start/publikationen.html

Additional safety plans can be found on the Internet.

Documentation usable in court

In the event that charges are filed and criminal proceedings are initiated – possibly only after the injuries have partially or completely healed – with a possible forensic medical examination, the medical documentation of the primary injury can play a decisive role. In order to ensure the best possible assessability of the photographed findings, the images should meet certain quality standards listed below.

The taking of photographs requires the patient’s declaration of consent. The rejection of such photographic documentation by the person concerned should be documented. Preventing damage to health naturally takes precedence over documentation. Whenever possible, however, photographic documentation should be performed prior to wound care, since sutured skin tears, for example, can often no longer be assessed with regard to their mechanism of origin. In the case of bloody or contaminated wounds, it is recommended to take images first in the original and then in the cleaned state. The photo-documentation should always be done with a scale (e.g. ruler) to allow a quantitative assessment of the size of the injuries also afterwards. The prerequisite for this is that the scale and the findings are in the same plane. If no scale is available, an object of known size (e.g. coin) can be photographed in exceptional cases. Images should be taken at right angles to the plane in which the injury is located to reduce perspective aberrations. In order to allow an anatomical assignment of the injury localization, an overview image of the affected body region should be taken first, followed by detailed images of the findings (Fig. 4) [8]. In some cases, it may also be useful to photographically record the absence of findings (e.g., uninjured neck when gagging is indicated). If strangulation is claimed, it is also recommended to document the (non)presence of petechiae in the ocular conjunctiva, oral vestibular mucosa, facial skin, and skin behind the ears.

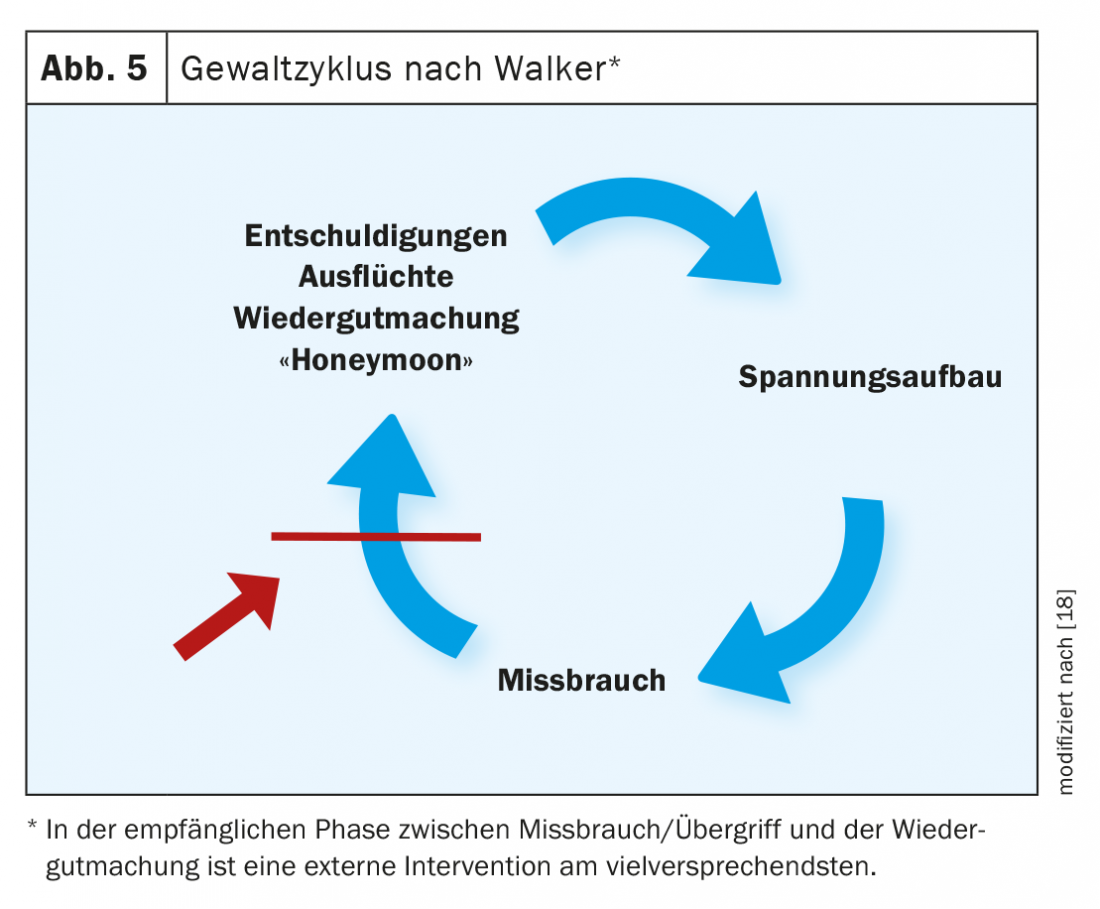

Development of violence/cycle of violence according to Walker

According to the annual statistics of the Bern Police from 2018, 75% of the cases were repeat offenses [9]. The study by Hostettler-Blunier et al. showed that in the medical setting, 57% of sufferers presented multiple times for HG [4]. The reasons why victims remain in a violent relationship are complex and often incomprehensible to outsiders. Apart from children and financial security, one of the main reasons is the belief that everything will change for the better if the person concerned only makes enough effort and no longer provides reasons that lead to a renewed escalation of violence. This hope and the point in time at which the victims are most receptive to external intervention is shown in simplified form in Walker’s cycle of violence (Fig. 5). The outbreak of violence is followed by a phase of calm, in which the victims initially either avoid each other altogether or are separated by the police. This phase should be used to proactively inform victims of violence about possible support services or to connect them directly to victim support services. As soon as the phase of remorse, the “honeymoon” sets in, in which the person who committed the crime or those affected actively seek closeness to the other person and the crime is trivialized, it again becomes difficult for those affected to break away from the relationship and seek external help. Based on this fact, victims of HG who present to their primary care physician, an emergency department, or an urgent care facility following an assault are considered to be “in an emergency situation.” In many cases, the primary objective here is not to provide urgent medical care for injuries, but to counsel them in the vulnerable phase regarding victim assistance and, if necessary, to proactively schedule appointments with their consent.

Excursus Legal Aspects: Official offense versus right to report/obligation to report

Since 2004, crimes in the area of HG are official offenses (simple assault, repeated assault, threat, sexual coercion, rape). This means that as soon as the prosecuting authority (police/prosecutor’s office) has knowledge of the case, it must investigate and prosecute it ex officio. The term official offense repeatedly leads to confusion among medical personnel and confusion with the obligation to report. It should be pointed out once again that the concept of an official offense refers to the hearing on the part of the law enforcement agency and is not to be equated with a medical reporting obligation. Whether specific medical reporting obligations/rights exist with regard to injured persons is set out in the relevant federal laws as well as cantonal legislation (usually in the relevant cantonal health law). An overview of the status of national and cantonal legislation on the protection of persons affected by violence can be found on the website of the Federal Office for the Equality of Women and Men EBG (www.ebg.admin.ch/ebg/de/home/themen/haeusliche-gewalt/gesetzgebung.html). Many police corps have specialized units for HG or threat management for HG. Cases of serious threat can be discussed anonymously with them. If an interdisciplinary assessment reveals an increased risk potential, the further procedure depends on the cantonal legislation.

Even if the right to report exists, a report should, whenever possible, be made with the consent of the person concerned. The decision to exercise a reporting right against the patient’s will must be carefully considered in each individual case. Here, a possible violation of the relationship of trust between doctor and patient must be weighed against the protection of the person concerned from future assaults.

Excursus Children and Domestic Violence

Children who live in families with HG are always affected. The Optimus study on child vulnerability in Switzerland, published in 2018, showed that approximately 18.7% of child vulnerability reports were co-occurring with HG. Extrapolated to the whole of Switzerland, this results in between 23-38 per 10,000 children in Switzerland [10]. Another study from the Violence Medical Unit of the University Hospital of Lausanne revealed that 75% of the cases involved children between 0-18 years of age, with the largest proportion being between 0-6 years of age [11]. Studies show that neglect and maltreatment (emotional, psychological and physical) of children are more common in families with HG [12], resulting in clinically psychologically relevant abnormalities in 30-40% [13]. Preventive approaches such as the Hague Protocol, in which all families with minor children presenting on an adult emergency due to HG, among other reasons, are presented to a child protection group/agency [14], are also used in Switzerland [15] or are being researched [16]. It is important in the family doctor’s work to inquire about the children in the family concerned, the degree of danger to the children, and to work out a joint strategy with the persons concerned regarding a report of danger to the child’s well-being. If there is a risk to the well-being of a child, but the family concerned does not want to take the initiative, a medical report to the child and adult protection authority (KESB) must be considered. According to Art. 314c para. 2 ZGB [17], persons subject to professional secrecy under the Criminal Code are entitled to report if the report is in the child’s best interests. Whether reporting is in the child’s best interest is difficult to assess because of intrafamily conflict.

Summary

Figures on doctor-patient contacts in the context of HG are collected irregularly in Switzerland. The last major healthcare survey showed that just over 80% of physicians had cared for at least one person affected by HG in the past year. From a medical point of view, patient care is often limited to the treatment of minor injuries (bruises/hematomas/crush lacerations) and thus does not per se constitute an indication for emergency medical presentation. Nevertheless, those affected by HG should be given a full hearing as quickly as possible because they are in a personal predicament. Thus, safety issues must be clarified with regard to both the person concerned and any children living in the family. In addition, according to the cycle of violence, victims of violence are more receptive to possible external help from victim assistance agencies or other interventions shortly after the assault. HG rarely ends spontaneously or after an initial intervention. This should not stop us from offering help again and again, without prejudice. This in the hope that it is precisely this time that help will lead to the final step out of the spiral of violence.

Take-Home Messages

- Domestic violence is usually not a medical emergency, but a personal emergency.

- Only about a quarter of those affected by violence share their experiences with their doctor.

- Minimal care includes documentation that can be used in court, clarifying the safety of victims including children, and handing out materials from victim assistance agencies.

- If possible, photo documentation should be made before wound care with scale, overview and detail photos.

Literature:

- Swiss Confederation. Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. Swiss Confederation 2018. Available at: www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/20162518/index.html.

- Switzerland, Section Crime and Criminal Law. Police crime statistics (PKS): annual report 2019 of police-registered crimes 2020. Available at: www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home.assetdetail.11147486.html.

- Krüger P, Lätsch D, Voll P, et al: Dealing with domestic violence in medical care. Bern University of Applied Sciences/ School of Social Work Valais /University of Lucerne 2019.

- Hostettler-Blunier S, Raoussi A, Johann S, et al: Domestic violence at the University Emergency Center Bern: a retrospective analysis from 2006 to 2016. Praxis 2018 (August); 107(16): 886-892.

- Killias M, Simonin M, de Puy J. (eds.): Violence experienced by women in Switzerland over their lifespan: results of the International Violence against Women Survey (IVAWS). Berne: Stämpfli 2004.

- Switzerland, Crime and Criminal Justice Section, Switzerland, Federal Statistical Office. Police Crime Statistics (PKS): Annual Report 2015, 2016. Available at: www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/kriminalitaet-strafrecht/polizei/betaebungsmittelsubstanzen.assetdetail.350887.html.

- Rosin C, Hennings E, Gerlach K, et al: Emergency situation: domestic violence. Swiss Med Forum 2020; doi: emh.ch/smf.2020.08495.

- Verhoff MA, Kettner M, Lászik A, Ramsthaler F: Digital Photo Documentation of Forensically Relevant Injuries as Part of the Clinical First Response Protocol. Deutsches Aerzteblatt Online 2012 (September 28). Available at: www.aerzteblatt.de/10.3238/arztebl.2012.0638.

- Bern Intervention Center against Domestic Violence. Domestic violence in the canton of Bern – annual statistics 2018. General Secretariat of the Police and Military Directorate of the Canton of Berne, Berne Intervention Center against Domestic Violence. Available at: %20im%.

- Schmid C, Jud A, Mitrovic T, et al: Kindswohlgefährdung in der Schweiz-Formen, Hilfen, fachliche und politische Implikationen. UBS Optimus Foundation, 8098 Zurich 2018. Available at: www.kinderschutz.ch/media/fzch1zav/optimus_iii_de.pdf.

- De Puy J, Radford L, Le Fort V, Romain-Glassey N: Developing Assessments for Child Exposure to Intimate Partner Violence in Switzerland – a Study of Medico-Legal Reports in Clinical Settings. J Fam Viol 2019; 34(5): 371-383.

- McGuigan WM, Pratt CC: The predictive impact of domestic violence on three types of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect 2001; 25(7): 869-883.

- Himmel R, Zwönitzer A, Thurn L, et al: The psychosocial burden of children in women’s shelters: Results of a pilot study in five women’s shelters. Neuroscience 2017; 36(03): 148-155.

- Diderich HM, Fekkes M, Verkerk P, et al: A new protocol for screening adults presenting with their own medical problems at the Emergency Department to identify children at high risk for maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl 2013; 12: 1122-1131.

- Cheseaux JJ, Duc Marwood A, Romain Glassey N.: Exposition de l’enfant à des violences domestiques – Un modèle pluridisciplinaire de détection, d’évaluation et de prise en charge. Rev Med Suisse 2013; 9: 398-401.

- Scholer M: Small effort, big effect. Schweiz Ärzteztg 2018; 16: 527-528.

- SR 210 – Swiss Civil Code of 10 December 1907 (as at 1 January 2021). Available at https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/24/233_245_233/de.

- Walker LE: The Battered Woman. Harper&Row Publishers, ins., New York 1979.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2022; 20(1): 12-16.