The motto of this year’s continuing education conference of the College of Family Medicine (KHM) was “Opposites: Wet – Dry”. Consequently, the first keynote presentation was dedicated to heart failure. Prof. Dr. med. Thomas Suter, Bern, explained in his lecture that for the assessment and treatment of the heart failure patient, the question “Warm or cold?” is at least as important as the question “Wet or dry?”.

“To assess a heart failure patient, you need to know what the perfusion is and what his fluid status is,” said Prof. Thomas Suter, MD, Bern, at the beginning of his update presentation. According to the revised European guidelines, heart failure is divided into Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction (HF-REF) and Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HF-PEF) [1]. HF-REF is defined by typical heart failure symptoms (orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea) and findings (volume overload with congested jugular veins and peripheral edema) and a left ventricular ejection fraction <45%. Patients with HF-PEF show the same clinical symptoms and signs, but their left ventricular ejection fraction is not or only slightly reduced and the left ventricle is not dilated. Nevertheless, these patients are heart failure patients because the function of the heart is no longer normal. “The distinction between HR-REF and HF-PEF is so important because you have to follow two different therapeutic pathways with these patients,” Prof. Suter emphasized. Men are slightly more likely to have HF-REF (58%), whereas among women, two-thirds have HF-PEF [2]. Looking at the pressure curve in the heart, it is not the left ventricular pump function that is decisive for the definition of heart failure, but the end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP). If this is elevated, heart failure is present. HF-REF typically occurs after myocardial infarction and corresponds to systolic dysfunction. The left ventricle is dilated to a greater or lesser degree, pump function is impaired, and, as a result, LVEDP is elevated. “If we translate that into the clinic, this patient has decreased perfusion. He is cold. And yet he is volume overloaded,” Prof. Suter explained. In contrast, in HF-PEF, which develops, for example, after long-standing arterial hypertension, the left ventricle is not enlarged, but the wall thickness is, left ventricular pressure is increased, and pump function is preserved. However, because of diastolic dysfunction, end-diastolic pressure is also elevated in this case. “This patient’s perfusion is normal. She is warm. And yet she is volume overloaded,” Prof. Suter summed up, emphasizing, “But you don’t need any apparatus to judge this, just your eyes and hands.”

Clinical examination

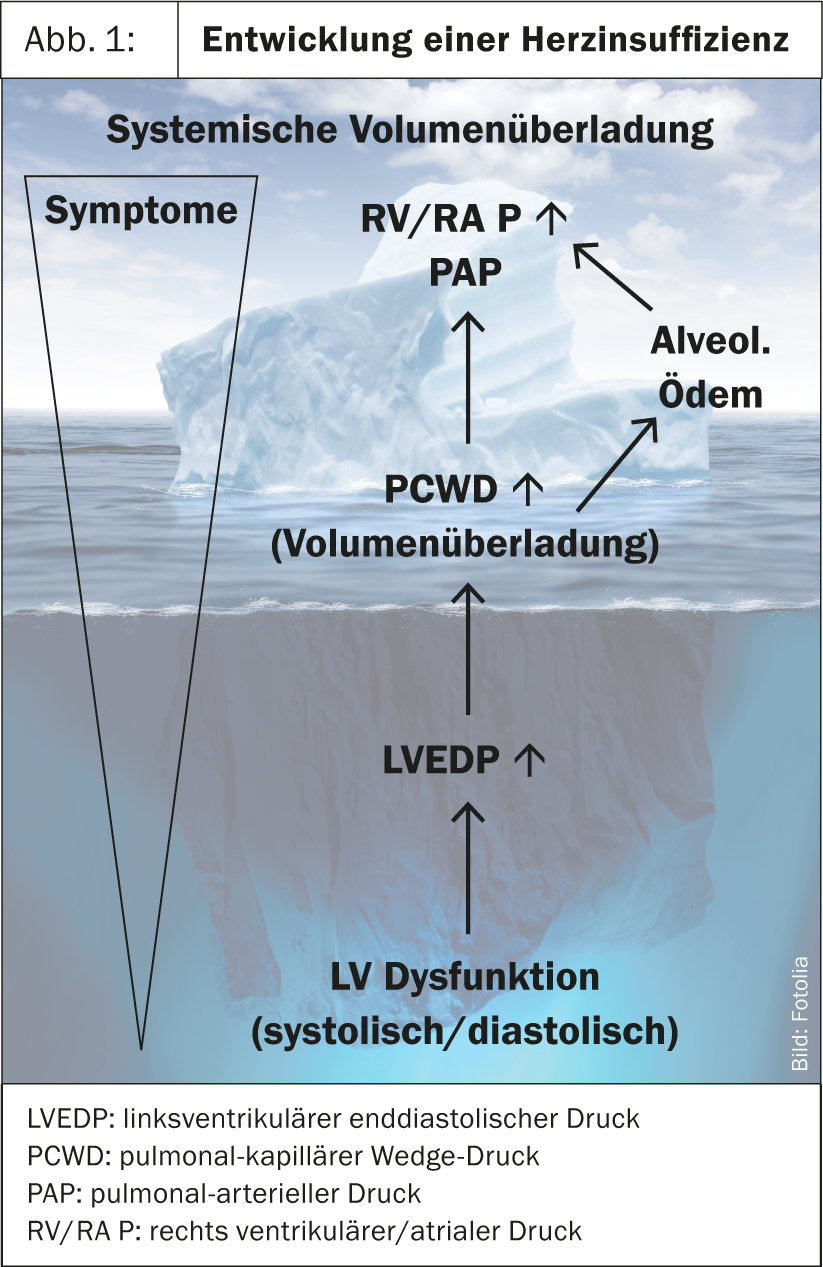

Before the patient presents with symptoms of heart failure, much has already happened. Therefore, Prof. Suter referred to the image of an iceberg (Fig. 1). One of the first signs of heart failure is increased LVEDP, manifested by a third heart sound on auscultation. Subsequent pulmonary volume overload is readily demonstrated radiologically. Only when alveolar edema occurs do patients then complain of dyspnea, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. “Ask the patient if, when he goes to the toilet during the night, he can lie back in bed immediately afterwards. The patient with paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea will tell you that he can’t and has to wait 10-15 min, otherwise he will have respiratory distress while lying down,” Prof. Suter explained.

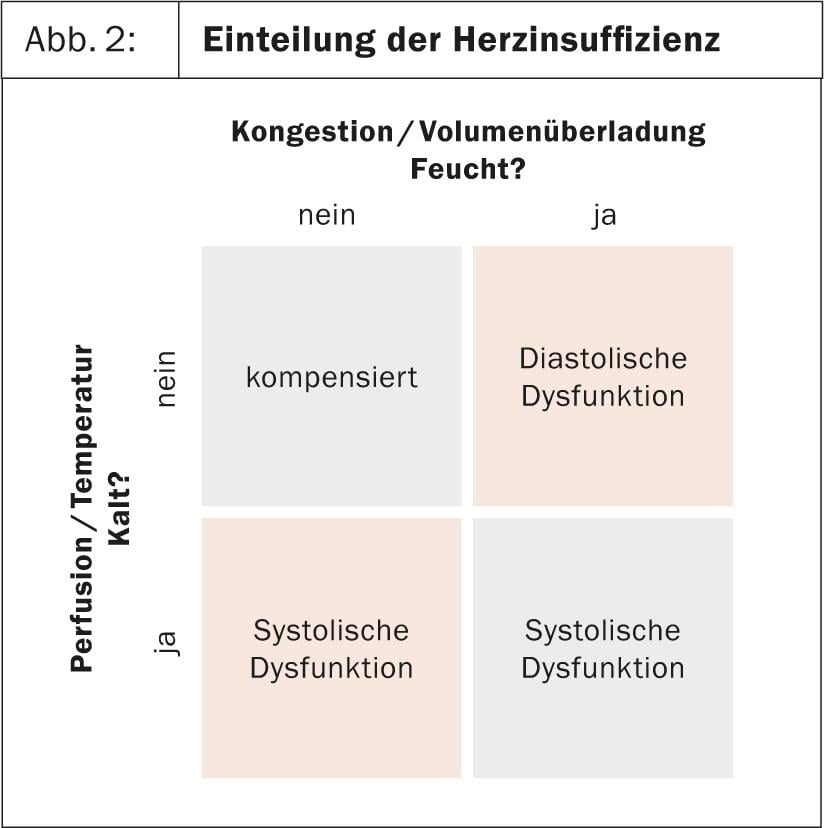

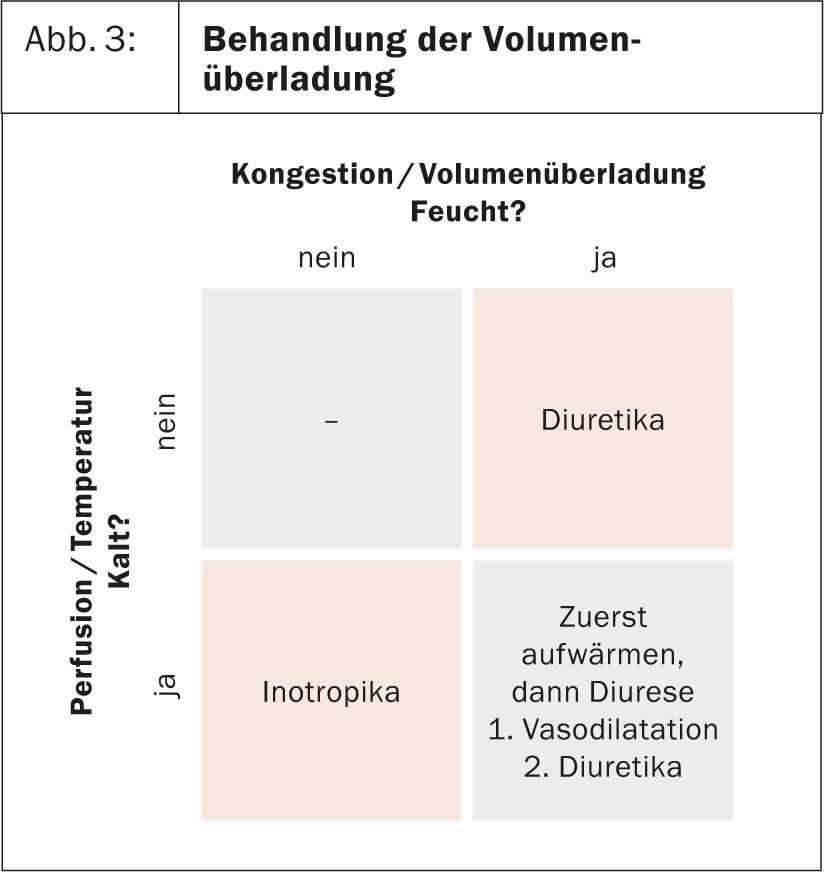

Fluid status is assessed clinically by neck veins and peripheral edema, and perfusion is assessed by patient temperature. “I always have a good reason to shake hands with my patients when I greet them,” Prof. Suter emphasized. By assessing these two parameters, patients can be easily classified (Fig. 2) and directed to the appropriate treatment (Fig. 3). Volume-overloaded patients who are warm, i.e. whose perfusion is good, are predominantly treated with diuretics. In those who are cold, perfusion must be improved first, e.g. with an ACE inhibitor, before volume status is optimized with diuretics. The rare patients who are not volume overloaded but are cold present a therapeutic challenge.

Treatment of the HF-REF

Diuretics: Due to pharmacokinetics, diuretics must be administered several times per day. Torasemide, which has a slightly longer half-life than furosemide (6 hr vs. 2.7 hr), has proven best in practice. “When we talk about diuretics, we also have to talk about salt,” Prof. Suter said. Patients who are only just compensated may acutely decompensate solely due to excessive salt intake (e.g. fondue, soup), so it is very important to explain this to patients. While salt restriction is of utmost importance, fluid restriction makes no sense. A good measure of volume status is weight, which should be checked daily.

ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: Once the volume status is balanced, the vasodilators (ACE inhibitors or, in the case of intolerance, angiotensin receptor blockers) are used in a second step. Here it is important to remember that virtually all side effects (increase in creatinine and retention parameters, orthostasis) of these drugs are due to dehydration of the patient. “Keep the patient, if you give him ACE inhibitors, rather on the wet side,” Prof. Suter therefore advised.

β-Blocker: As soon as the patient is clinically stable, the current guidelines of the Swiss Heart Failure Working Group recommend the administration of a cardioselective β-blocker [3]. This should be started with a low dose, but then increased to the maximum tolerated dose. The main effect of β-blockade is to tonify the heart to induce “reversed remodeling,” that is, to make the heart smaller again and thus more efficient. When dosing the β-blocker, however, it is always important to remember that performance depends on cardiac output, which is increased under stress via an increase in pulse. If a patient becomes too β-blocked, his performance decreases because of chronotropic incompetence. Elderly patients, who often already have sinus node dysfunction, are particularly at risk.

Aldosterone antagonists: for patients who are still symptomatic (NYHA ≥2) even with extended therapy with diuretics, ACE inhibitors, and ββ-blockers and have a left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35%, an aldosterone antagonist should also be given.

Ivabradine: If the patient is still symptomatic and there is sinus tachycardia of >70/min (but not atrial fibrillation), the above guidelines recommend that ivabradine be additionally administered, and patients in whom the β-blocker cannot be maximally dosed seem to benefit most [4, 5].

Treatment of HF-PEF

The guidelines say very little about the treatment of heart failure with preserved pump function. First and foremost, the underlying disease (hypertension, diabetes, myocardial ischemia, obesity) should be treated optimally. Symptomatically, the filling pressure is reduced with the help of diuretics . Balance of fluid status is particularly important in these patients, but rhythm control and maintenance of sinus rhythm are also of great importance. “And what else can we offer these patients?” asked Suter. “Unfortunately, very little. There is currently little evidence that these patients would benefit from ACE inhibitors, sartans, or β-blockers, except to treat any underlying arterial hypertension.”

Source: “Wet and Cold? Update of Heart Failure Therapy”, keynote lecture 1 at the 15th Continuing Education Conference of the College of Family Medicine (KHM), June 20-21, 2013, Lucerne.

Literature:

- McMurray JJ, et al: ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 1787-1847.

- Kitzman DW, et al: Importance of heart failure with preserved systolic function in patients > or = 65 years of age. CHS Research Group. Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Cardiol 2001; 87: 413-419.

- www.heartfailure.ch

- Swedberg K, et al: Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet 2010; 376: 875-885.

- Böhm M, et al: Heart rate as a risk factor in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): the association between heart rate and outcomes in a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010; 376: 886-894.