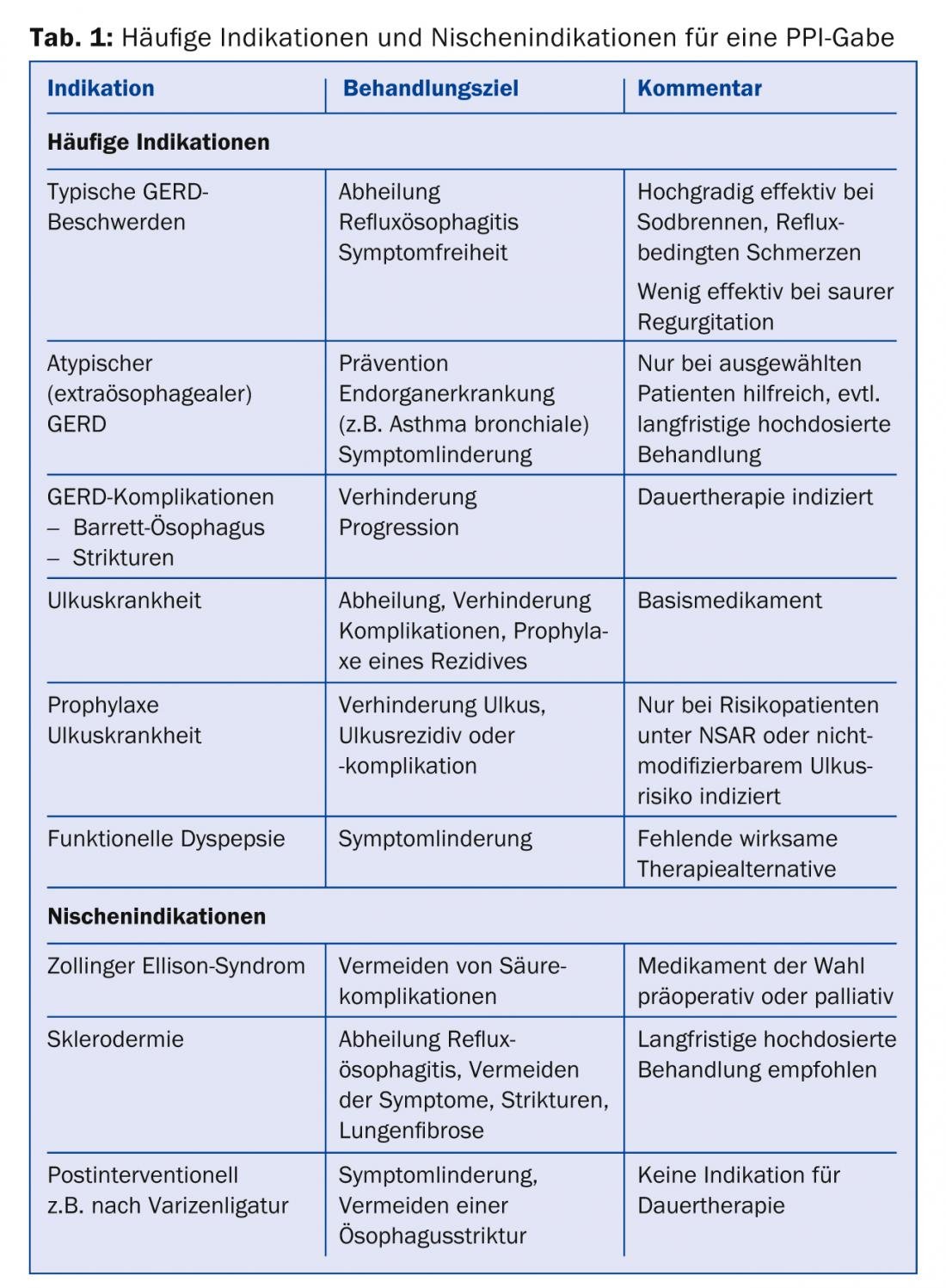

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the third most commonly used class of drugs in current clinical practice worldwide after antibiotics and statins (Table 1). These highly potent acid inhibitors effectively cure and improve symptoms in gastroesophageal reflux disease as well as other diseases caused by stomach acid. However, with the widespread and often prolonged use of PPIs, even small risks to health are relevant. The task for the primary care physician is to avoid unnecessary PPI use without depriving patients with good indications of this effective medication. The following article provides an overview of the indications and risks in use.

What is the role of PPIs in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)? PPIs are the most effective class of medications for GERD. Due to the availability of PPIs, most patients with typical reflux symptoms (e.g., heartburn, acid regurgitation) can be treated well by the primary care physician or even by self-medication with PPIs [1,2]. Further clarification or referral to the gastroenterologist is only necessary for the treatment of refractory reflux symptoms. It is also important to keep reviewing the indication for continuous therapy with PPI in symptom-free patients. Often the dose can be reduced and up to 40% of all patients remain symptom-free for months even after discontinuation of PPIs [3]. This proportion can be further increased by administration of on-demand medication (e.g. antacids, alginates such as Gaviscon®) [2].

Under PPI, reflux esophagitis and peptic strictures can heal or be prevented as complications of GERD [4]. Barrett’s esophagus is another clinically important consequence of GERD and can lead to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus in approximately 0.2% per year [5]. Case-control studies suggest that PPIs may prevent progression to carcinoma in this setting [6]. The results of the large prospective randomized ASPECT trial will soon be available to definitively clarify this issue [7]. In our opinion, continuous therapy with a PPI is already indicated in Barrett’s esophagus.

Extraesophageal manifestations of GERD include chronic cough, hoarseness, and globus sensation. In these patients, the relationship between reflux and symptoms is less clear, and ORL complaints (chronic sinusitis, “post-nasal drip”) and pneumologic diseases may contribute to the pathogenesis [1]. The success rates of PPI treatment are correspondingly more modest [8].

If symptoms persist, the general practitioner has two options: first, empiric PPI treatment at twice the standard dose for eight to twelve weeks, and second, objective pH measurement to determine the severity of esophageal acid exposure and the relationship between reflux and extraesophageal symptoms [8]. The patient should be involved in this decision. It is important to note that in case of unsuccessful PPI treatment or negative pH measurement, PPI should be stopped.

Indication peptic ulcer

PPIs are the basic medication for the treatment of peptic ulcer and its complications. Thus, in the bleeding situation, neutralization of gastric pH can activate blood coagulation and limit bleeding [9]. In addition, within a few weeks, most gastric or duodenal ulcers heal with PPI therapy [10]. PPIs are also part of H. pylori eradication therapy. Again, once the ulcer has healed and the risk factor has been eliminated, the PPI should be stopped. Continuous PPI therapy for the prophylaxis of ulcer development or ulcer recurrence is indicated in high-risk patients taking NSAIDs and in patients with previous ulcers and non-modifiable risk factors [11].

Indication functional dyspepsia

PPIs are effective in the treatment of functional dyspepsia (FD) in some cases and can also be given empirically in the absence of alarm symptoms and after exclusion of H. pylori infection. Unfortunately, the success rate of PPI for this indication is low (“number needed to treat”, NNT: 10, compared to NNT 2-3 for typical reflux symptoms) [12].

Non-response to PPI administration

Not all symptoms of GERD respond to PPI treatment. For example, symptoms of volume reflux can be reduced by medication in the best case. Even for patients with typical GERD symptoms (Fig. 1), the effect of PPI is not perfect.

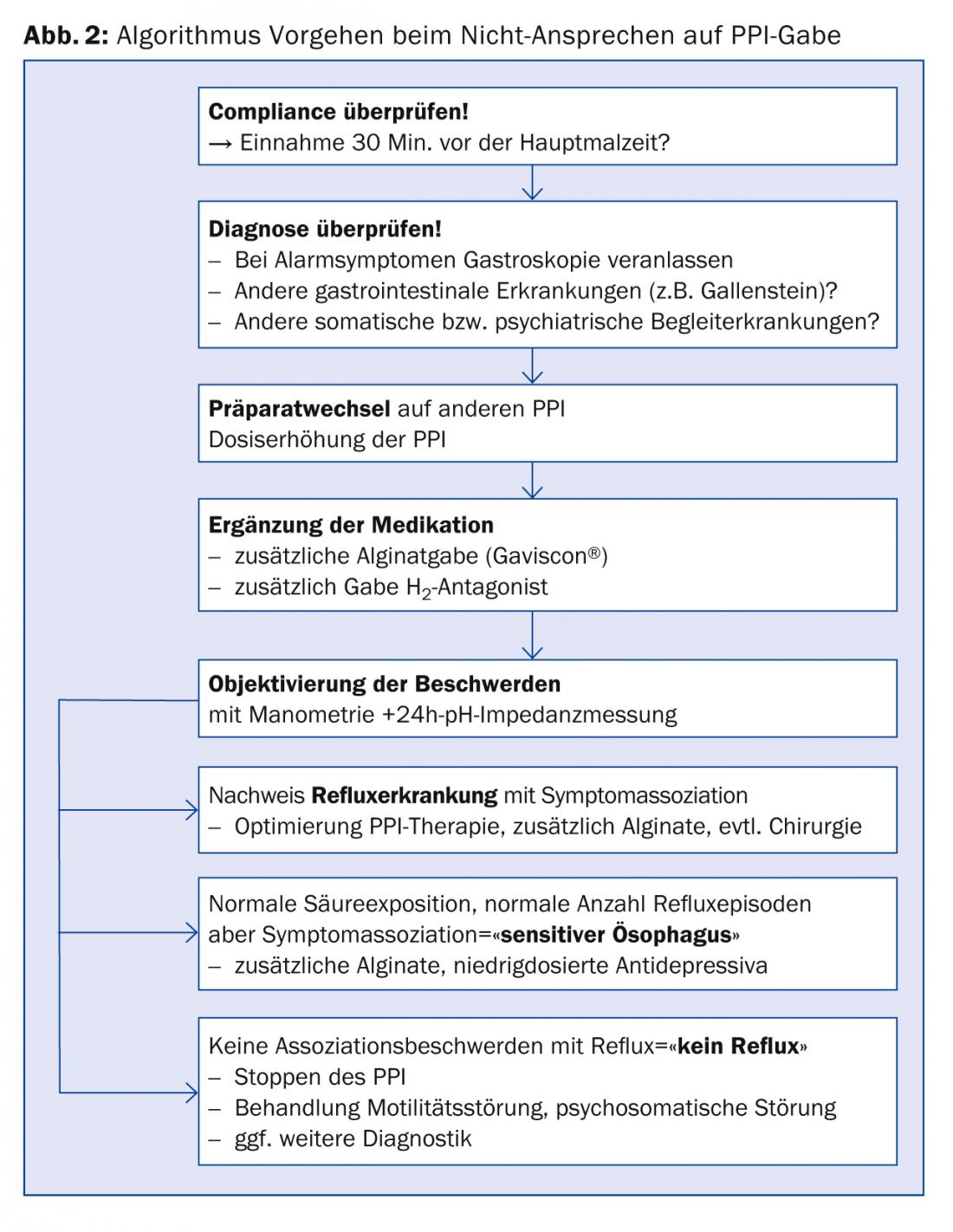

Although up to 90% of all patients respond to treatment, approximately one-third of all patients on continuous PPI therapy do not become completely symptom-free [1,2]. Furthermore, a large number of GERD patients take over-the-counter medications in addition to PPI [13]. We suggest a sequential approach in case of an unsatisfactory response to PPI (Fig. 2) .

An alginate preparation (e.g., Gaviscon®) should be tried if symptoms are typical under PPI. Alginates form a viscous layer in front of the esophageal inlet and can prevent acid and non-acid reflux [14]. In addition, the PPI could be changed and/or the dose increased.

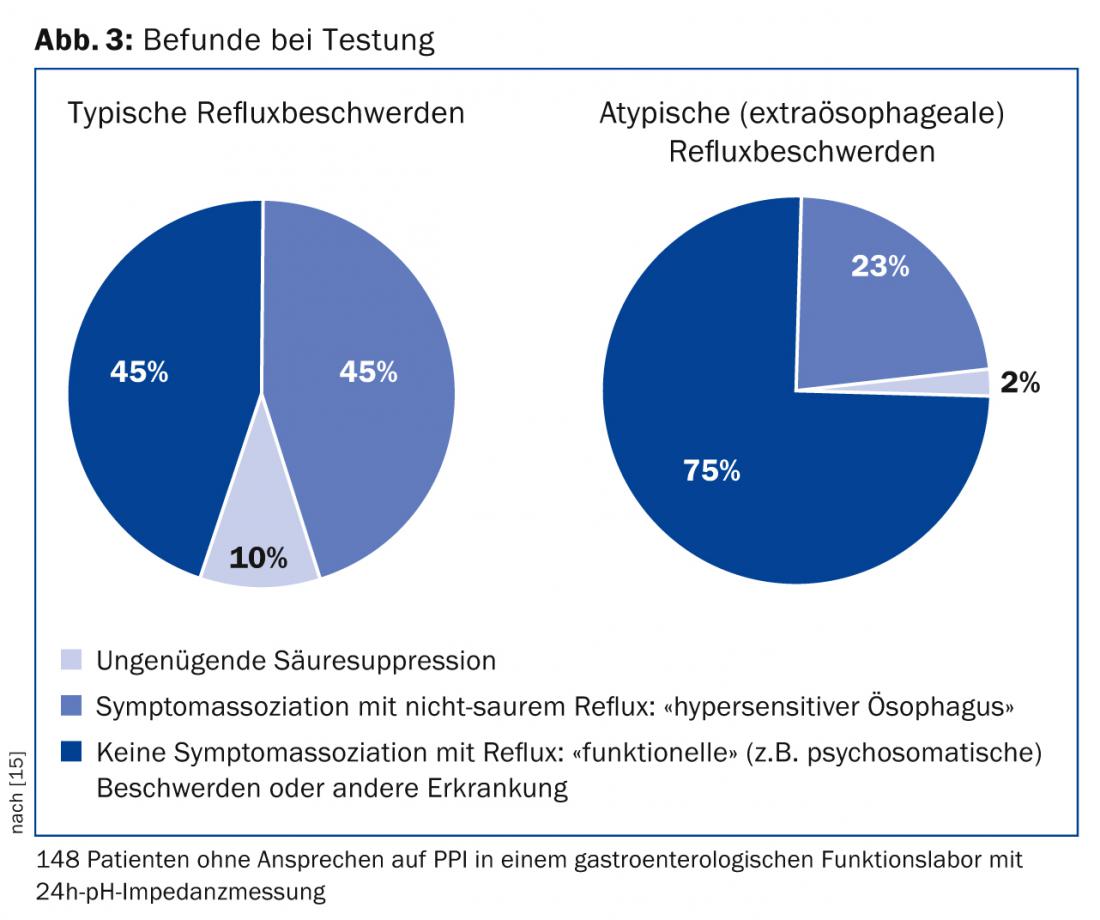

In case of atypical symptoms or non-response to PPI despite the mentioned measures, further gastroenterological diagnostics should be performed. Gastroscopy is indicated first to exclude peptic ulcer or neoplasia. If the findings are normal, manometry and pH impedance measurement should be performed to identify the cause of the symptoms [1,2]. Thus, only about half of all patients with “reflux symptoms” referred to a gastroenterology functional laboratory have objectifiable reflux disease (Fig. 3) [15]. For example, patients suffering from achalasia are initially misdiagnosed as GERD patients in approximately 40% of cases and treated with PPI [16].

An exact diagnosis of the refractory symptoms then enables targeted treatment (Figs. 2 and 3) . If acid reflux is confirmed as the cause of the complaint, acid suppression must be further optimized. In the absence of pathologic reflux but existing symptom association between reflux and heartburn or thoracic pain (so-called “sensitive esophagus”), alginates may be given in addition to PPIs. In addition, low-dose antidepressants (e.g., amitriptylline 25 mg nocté) can be used to modulate visceral sensitivity. In the absence of reflux disease and symptom association, the PPI can be discontinued. Instead, a motility disorder or a psychosomatic disorder should be treated, if necessary, or further diagnostics should be initiated.

Risk acid rebound

It is consistent with clinical experience that heartburn often worsens briefly after discontinuation of a PPI. Reflux symptoms can be induced after short-term PPI administration even in previously symptom-free subjects [17]. This rebound effect may make it difficult for patients to discontinue PPIs and may contribute to unnecessary PPI administration [18]. If rebound symptoms occur after discontinuation, the PPI should be gradually reduced (e.g., one week single standard dose, one week half standard dose). Additionally, we recommend antacids or alginates as needed during weaning.

Other risks of a PPI

Contrary to initial concerns, PPIs do not increase the risk of gastric cancer [19]. Many case-control studies have found an association of cancer risk with the indication for PPI treatment (GERD, gastric ulcers, etc.) but not with PPI use [20]. On the other hand, a PPI may mask symptoms of gastric cancer. Therefore, gastroscopy is mandatory for alarm symptoms before empiric PPI treatment and should always be considered if PPI efficacy is insufficient.

The loss of the antibacterial effect of gastric acid increases the risk of infectious enteritis with Shigella and Salmonella, among others [21]. Especially for hospitalized patients or patients in need of nursing care, the risk increase regarding Clostridium difficile infections (HR 2.5) or pneumonias (HR 1.4) should be relevant [22]. In patients with cirrhosis, PPIs may not stop esophageal variceal bleeding but may increase the risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and should not generally be given in this patient group [23].

Physiologic considerations also suggest decreased absorption of vitamin B12, calcium, magnesium, and iron with PPI use [24]. With today’s abundance of food with adequate amounts of vitamins and minerals, this risk is rarely relevant [24]. Nevertheless, in case of complaints compatible with malnutrition of these mentioned substances should be generously monitored. Association studies have also identified osteoporosis as a possible complication of long-term PPI use (HR for fracture risk 1.25) [25]. Importantly, all of these risks were found in case-control studies, but not in large prospective randomized trials, and thus are not free from the influence of potential confounders.

Drug interactions of PPIs and other risks are summarized in Table 2. An initially feared drug interaction between PPI and clopidogrel was refuted in recent studies. For example, PPIs carry the theoretical risk of clopidogrel blockade because they can block cytochrome CYP2C19, which is important for clopidogrel activation. Nevertheless, in a large study in which patients received either clopidogrel alone or together with a PPI after coronary stent insertion, the risk of cardiac adverse events was exactly the same in both study arms with fewer gastrointestinal adverse events with PPI [26]. Thus, the pharmacological interaction of PPI and clopidogrel is not relevant in practice. This discourse shows how physiological considerations can occasionally mislead and how strongly the confounder “morbidity” can feign relevant interactions in case-control studies.

Adequate indication decisive

Despite all the advantages, it is important to warn against the uncritical use of these drugs: Estimates suggest that 25-75% of all patients treated with PPI do not have an adequate indication. In typical case series of hospitalized patients, 20% take PPI on admission, 40% are started on a PPI during hospitalization, and 50% are found on a PPI in discharge medication [27]. This is almost always without adequate indication and without a timing of a medication review being suggested in the discharge letter. Frequently hospitalized patients are thus likely to be treated frequently with PPI in the outpatient setting as well [28]. This group of patients is particularly susceptible to the problems mentioned above.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- The introduction of PPIs to the market as safe and effective inhibitors of acid secretion has had a major, positive impact on the treatment of many diseases of the stomach and esophagus.

- Nevertheless, it is important to warn against the uncritical use of these drugs.

- It remains the responsible task of the primary care physician to stop the “unnecessary” PPI, to continue the “necessary,” helpful PPI at the lowest effective dose, and most importantly, to safely distinguish the two situations.

A RETENIR

- La mise sur le marché des IPP comme inhibiteurs sûrs et efficaces de la sécrétion d’acide a eu un important effet positif sur le traitement de nombreuses maladies de l’estomac et de l’œsophage.

- Toutefois une mise en garde contre une utilisation irrationnelle de ces médicaments est nécessaire.

- Il subsiste la tâche à haute niveau de responsabilité du médecin de famille consistant à arrêter les IPP “inutiles”, à poursuivre les IPP “nécessaires” aux doses efficaces les plus faibles et avant tout à différencier avec précision les deux situations.

Prof. Dr. med. Mark Fox

PD Benjamin Misselwitz, M.D.

Daniel Pohl, MD

Literature:

- Fox M, Forgacs I: Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. BMJ 2006; 332: 88-93.

- Tytgat GN, et al: New algorithm for the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008 Feb 1; 27(3): 249-256.

- Schwizer W, et al: The effect of Helicobacter pylori infection and eradication in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study. United European Gastroenterology Journal 2013; 1(4): 226-235.

- Castell DO, et al: Esomeprazole (40 mg) compared with lansoprazole (30 mg) in the treatment of erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97(3): 575-583.

- de Jonge PJ, et al: Barrett’s oesophagus: epidemiology, cancer risk and implications for management. Gut 2014 Jan; 63(1): 191-202.

- Singh S, et al: Acid-suppressive medications and risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2013 Nov 12.

- Jankowski J, Sharma P: Review article: approaches to Barrett’s esophagus treatment-the role of proton pump inhibitors and other interventions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004 Feb; 19 Suppl 1: 54-59.

- Sifrim D, Barnes N: GERD-related chronic cough: how to identify patients who will respond to antireflux therapy? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010 Apr; 44(4): 234-236.

- Sung JJ, et al: Intravenous esomeprazole for prevention of recurrent peptic ulcer bleeding: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009 Apr 7; 150(7): 455-464.

- Leodolter A, et al: A meta-analysis comparing eradication, healing and relapse rates in patients with Helicobacter pylori-associated gastric or duodenal ulcer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001 Dec; 15(12): 1949-1958.

- Chan FK, Sung JJ: Role of acid suppressants in prophylaxis of NSAID damage. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2001 Jun; 15(3): 433-445. PubMed PMID: 11403537.

- Wang WH, et al: Effects of proton-pump inhibitors on functional dyspepsia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Feb; 5(2): 178-185; quiz 40.

- Hungin AP, et al: Systematic review: Patterns of proton pump inhibitor use and adherence in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012 Feb; 10(2): 109-116.

- Sweis R, et al: Post-prandial reflux suppression by a raft-forming alginate (Gaviscon Advance) compared to a simple antacid documented by magnetic resonance imaging and pH-impedance monitoring: mechanistic assessment in healthy volunteers and randomised, controlled, double-blind study in reflux patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013 Jun; 37(11): 1093-1102.

- Mainie I, et al: Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut. 2006 Oct; 55(10): 1398-1402.

- Kessing BF, Bredenoord AJ, Smout AJ: Erroneous diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease in achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Dec; 9(12): 1020-1024.

- Reimer C, et al: Proton-pump inhibitor therapy induces acid-related symptoms in healthy volunteers after withdrawal of therapy. Gastroenterology 2009; 137(1): 80-87.

- Howden CW, Kahrilas PJ: Editorial: just how “difficult” is it to withdraw PPI treatment? Am J Gastroenterol 2010 Jul; 105(7): 1538-1540.

- Klinkenberg-Knol EC, et al: Long-term omeprazole treatment in resistant gastroesophageal reflux disease: efficacy, safety, and influence on gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology 2000 Apr; 118(4): 661-669.

- Tamim H, et al: Association between use of acid-suppressive drugs and risk of gastric cancer. A nested case-control study. Drug Saf 2008; 31(8): 675-684.

- Leonard J, Marshall JK, Moayyedi P: Systematic review of the risk of enteric infection in patients taking acid suppression. Am J Gastroenterol 2007 Sep; 102(9): 2047-2056; quiz 57.

- Howell MD, et al: Iatrogenic gastric acid suppression and the risk of nosocomial Clostridium difficile infection. Arch Intern Med. 2010 May 10; 170(9): 784-790.

- Goel GA, et al: Increased rate of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis among cirrhotic patients receiving pharmacologic acid suppression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012 Apr; 10(4): 422-427.

- Pohl D, et al: Do we need gastric acid? Digestion 2008; 77(3-4): 184-197.

- Gray SL, et al: Proton pump inhibitor use, hip fracture, and change in bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. Arch Intern Med 2010 May 10; 170(9): 765-771.

- Bhatt DL, et al: Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2010 Nov 11; 363(20): 1909-1917.

- Yachimski PS, et al: Proton pump inhibitors for prophylaxis of nosocomial upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding: effect of standardized guidelines on prescribing practice. Arch Intern Med. 2010 May 10; 170(9): 779-783.

- Arasaradnam RP, et al: Audit of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) prescribing: are NICE guidelines being followed? Clin Med 2003 Jul-Aug; 3(4): 387-388.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(6): 26-31