The most common benign biliary disease, cholecystolithiasis, can cause acute and chronic inflammation of the gallbladder and biliary obstruction. The therapeutic gold standard is laparoscopic cholecystectomy. There are innovative surgical techniques with decisive benefits for the patient.

In addition to the detailed pain history, further questioning focuses on the presence of signs of inflammation (fever, chills) and signs of cholestasis (pale stools, dark urine, itching, yellowing of the sclerae or skin). If local pain can be elicited with gentle pressure on the gallbladder fundus followed by deep inspiration, a positive Murphy sign is present.

Painless, palpable gallbladder with icterus indicates tumor-related biliary drainage obstruction (Courvoisier’s sign). Pressure pain in the right hypochondrium with elevated temperatures or local peritonism are expressions of an inflammatory process of the gallbladder. Acute cholangitis is typically characterized by icterus, right upper abdominal pain, and fever (Charcot triad).

Laboratory examination

Specific preoperative laboratory diagnostics include:

- Cholestasis enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase (AP), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT).

- Bilirubin

- Aspartate aminotransferase (ASAT)

- Alanine Aminotransferase (ALAT)

- Lipase

- Coagulation

- Small blood count

Imaging diagnostics

The method of choice for diagnosing gallstone disease is transabdominal sonography. The sensitivity for calculi in the gallbladder is over 95%. Sonography is still suitable for assessing the bile ducts and is used for differential diagnosis. If a tumor is suspected clinically and sonographically, a contrast CT should be ordered. MRCP has the highest sensitivity in cases of uncertain stone detection, suspected biliary tract calculi, or biliary tract abnormalities [1].

Differential diagnoses

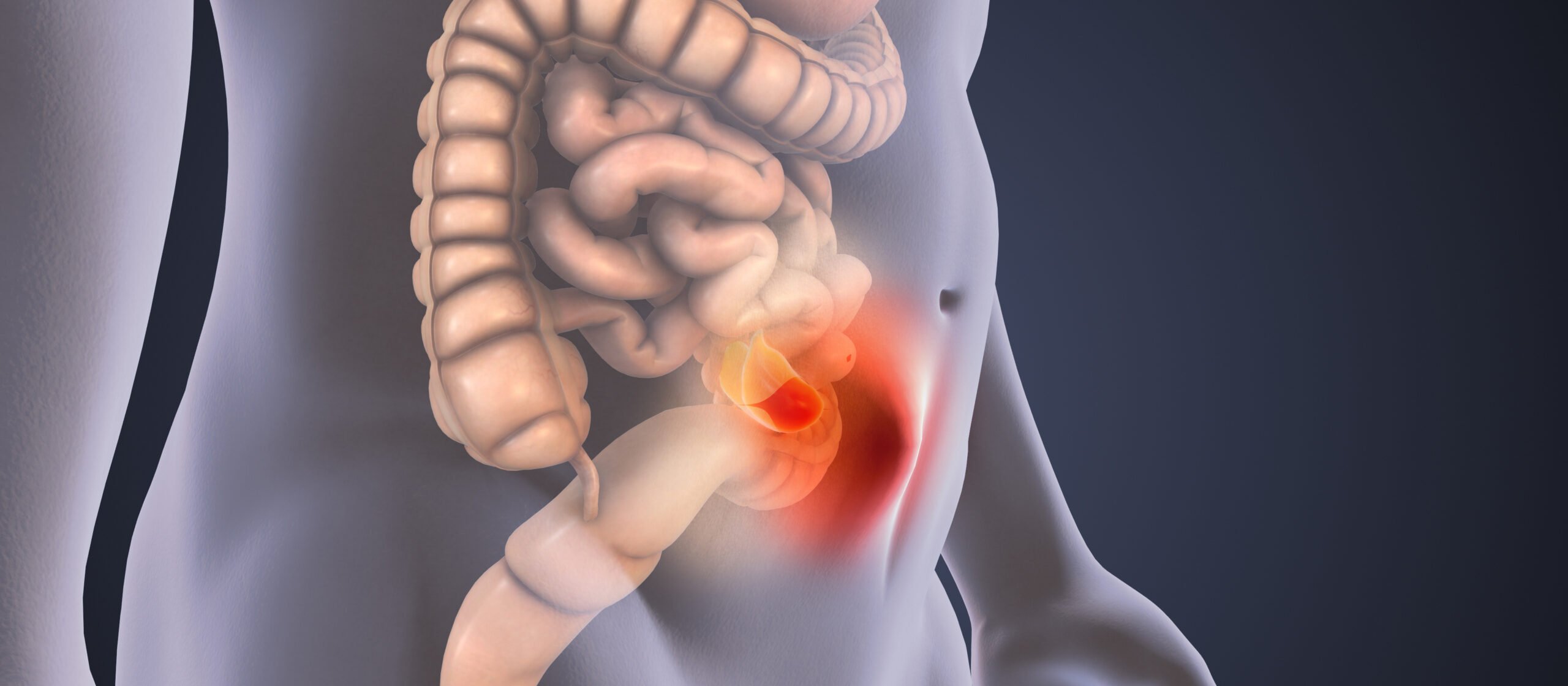

The main differential diagnoses are:

- Ulcer disease

- Nephrolithiasis

- Pancreatitis

- Appendicitis and tumors of the right-sided colon

- Ongoing thoracic pain due to basal pleurisy or posterior wall infarction.

In addition to the medical history, the clinical and laboratory findings and abdominal ultrasonography by an experienced examiner are important for the diagnosis. In case of specific suspicion, gastroscopy or colonoscopy should be performed preoperatively.

Therapeutic procedure

Conservative therapy: Conservative therapy of biliary colic is by means of food restriction (tea or water only) and spasmodic analgesia (N-butylscopolamine, metamizole sodium).

Pain spikes can be treated with opiates. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (diclofenac, indometacin) also have a good analgesic effect. For nausea and vomiting, infusion therapy is given and antiemetics are administered. Only in protracted cases the therapy is carried out on an inpatient basis.

Interventional methods for nonoperative treatment of gallstones include drug lysis therapy with ursodeoxycholic acid for small cholesterol concretions (<5-10 mm) [2]. The indication is limited to a few individual cases with a high surgical risk or at the patient’s request. Surgery should be performed for recurrent calculi.

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy has not been successful in gallstone disease because of high recurrence rates, complications, and a high time-cost factor.

Surgical therapy: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been the gold standard for surgical treatment of gallstone disease since the mid-1990s. As experience is gained and laparoscopic equipment improves, the indication for minimally invasive procedures becomes broader. There is a smooth transition to the therapy of challenging gallbladder pathologies and surgery-aggravating concomitants such as obesity, previous surgery, cardiopulmonary limitations, coagulopathies, and multimorbidity. Conservative, open gallbladder removal is now performed in only a few cases.

The most common reasons for conversion to open cholecystectomy are:

- Lack of clear anatomy

- Intraoperative complications (unstoppable bleeding, bile leak that cannot be localized, vascular or organ injury).

- Difficult preparation (atrophic sclerosing or acute cholecystitis).

- Inexperienced surgeon.

Indication and contraindication

The indication for laparoscopic cholecystectomy is recurrent symptomatic cholecystolithiasis or after endoscopically treated choledocholithiasis. If the patient has developed biliary pancreatitis as part of the stone removal process, cholecystectomy should be performed early (within one week of clinical recovery) in patients with mild pancreatitis [3]. In contrast, in patients with severe necrotizing pancreatitis, surgery should be performed only after clinical consolidation (after about six weeks at the earliest) [4].

According to current studies, acute cholecystitis should even be treated surgically within 24 hours of hospital admission [5,6].

Exceptional indications in asymptomatic stone carriers include a porcelain gallbladder, patchy wall calcifications (carcinoma rate up to 7%), and calculi >3 cm (nine- to tenfold increased risk of carcinoma). If the combination of cholecystolithiasis and gallbladder polyp >1 cm is found, surgery should be performed in any case regardless of the symptoms. In asymptomatic stone carriers, simultaneous cholecystectomy is recommended during major abdominal procedures (gastrectomy, colon rectum resection, liver resection) or as part of bariatric surgery. The risk of stone-related complications ranges from 10% to 15% after malabsorptive/restrictive bariatric surgery. Patients at particular risk are those who have undergone ileocecal resection (Crohn’s disease), short bowel syndrome (bile acid loss, disruption of calcium and lipid metabolism), and prolonged parenteral nutrition. Prophylactic surgery of asymptomatic gallstone carriers should be performed before heart transplantation (Table 1).

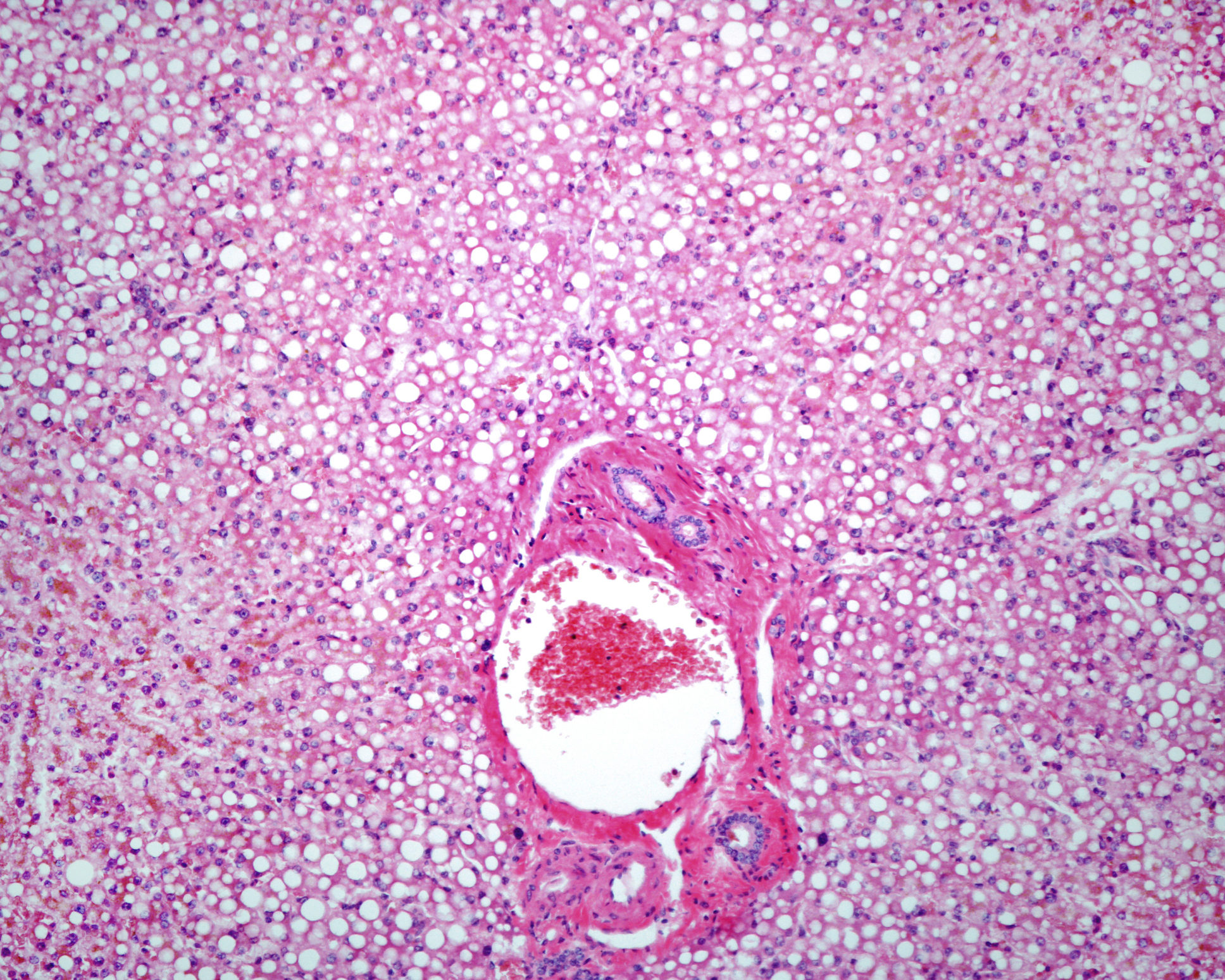

Contraindications to the minimally invasive procedure include a suspected diagnosis of gallbladder malignancy and the presence of severe septic disease. Asymptomatic cholecystolithiasis is not an indication for gallbladder removal. The patient is also considered to be an asymptomatic stone carrier if a single episode of biliary colic occurred more than five years ago. Other contraindications include:

- Prophylactic cholecystectomy

- Liver cirrhosis (Child C) or MELD score >8.

Surgical procedure laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Gallbladder removal is performed in the supine position with the legs spread and 30° anti-Trendelenburg position. The surgeon stands between the legs, the assistant stands on the left side of the patient and the instrumenting nurse is at the foot end (Fig. 1).

The technical process is quite standardized:

- Insert trocars: First, the abdominal cavity is inflated with CO2 gas via a Veress needle (capno-peritoneum) and a first trocar is inserted blindly through a 1.5 cm longitudinal incision at the side of the umbilicus. The other three trocars are placed under camera view and diaphanoscopy in the epigastrium (5-mm instrument trocar), in the area of the left extension of the medioclavicular line (10-mm working trocar), and through the rectus abdominis muscle hand-width below the right costal arch (5-mm working trocar). The triangulation between the optics (center position) and the two working channels is crucial (Fig. 2).

- Adjust gallbladder: After inspection of the abdominal cavity, the gallbladder is adjusted by elevating the right lobe of the liver. Existing adhesions must be released so that the gallbladder and hepatic hilus are easily visible. Using grasping forceps, the gallbladder is grasped at the junction of the infundibulum and the corpus and pulled caudally and laterally. By holding the liver against it, the Calot triangle stretches open (Fig. 3).

- Mobilize the infundibulum: Incision of the peritoneal covering close to the wall is made on the visible anterior surface and after folding over (medial, cranial direction of traction) on the posterior wall. The mobilization of the infundibulum thus achieved leads to an enlargement of the trigonum cystohepaticum.

- Dissect the cystic duct and cystic artery: Further dissection is performed from medial and lateral alternately by changing the direction of traction on the mobilized infundibulum. The cystic duct with its junction with the hepatocholedochal duct and the cystic artery are exposed. After secure identification of both structures, they are cut between clips (Fig. 4).

- Gallbladder out: The gallbladder is then released from its liver bed. It is important to dissect in the correct layers to avoid wall injury or penetration into the liver parenchyma (Fig. 5).

- Extract gallbladder: After exact hemostasis, irrigation of the right upper abdomen is performed with control of the clips and exclusion of a bile leak. The gallbladder is extracted in the salvage bag umbilically after fascial dilatation.

- Remove trocars and close fascial incisions: Under vision, all trocars are removed and fascial incisions larger than 5 mm are closed with suture. Insertion of a subhepatic drain is usually not required. Exceptions include deep opening of the hepatic parenchyma with possible peripheral biliary leak, bilious peritonitis, or uncertain closure of the cystic duct.

Routinely, intraoperative cholangiography is not performed concurrently with cholecystectomy. It is probably not useful because the detection of unexpected bile duct stones is less than 4% [7].

Single-port cholecystectomy

In recent years, modern technology has made it possible to further reduce the number of access routes to the abdominal cavity, so that today operations can be performed via a single access (port). This technique is called single-port surgery. Usually, a two to three centimeter incision is made at the umbilicus to access the abdomen and the single-port system is inserted. Thanks to the special instruments, even complete organs such as the gallbladder can be removed through this single access. What remains is a barely visible scar in the umbilicus, even in complicated operations (Fig. 6).

The single-port technique is a safe and effective method for gallbladder removal [8]. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed no difference in complication rates, postoperative pain, and length of hospital stay. However, a significant difference was found in the increase in the duration of surgery by twelve minutes. In terms of cosmetic outcome, patients favored the single-port technique [9]. The results are consistent with the experience of our center, where this method is used regularly.

Literature:

- Lammert F, et al: S3 guidelines of the German Society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases and the German Society of Visceral Surgery on the diagnosis and treatment of gallstones. Z Gastroenterol 2007; 45: 971-1001.

- Podda M, et al: Efficacy and safety of a combination of chenodeoxycholic acid and ursodeoxycholic acid for gallstone dissolution: a comparison with ursodeoxycholic acid alone. Gastroenterology 1989; 96: 222-229.

- Da Costa DW, et al: Same-admission versus interval cholecystectomy for mild gallstone pancreatitis (PONCHO): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386: 1261-1268.

- Nealon WH, Bawduniak J, Walser EM: Appropriate timing of cholecystectomy in patients who present with moderate to severe gallstone-associated acute pancreatitis with peripancreatic fluid collections. Ann Surg 2004; 239: 741-749.

- Banz V, et al: Population-based analysis of 4113 patients with acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg 2011; 254: 964-970.

- Gutt CN, et al: Acute cholecystitis: early versus delayed cholecystectomy, a multicenter randomized trial (ACDC study, NCT00447304). Ann Surg 2013; 258: 385-393.

- Metcalfe MS, et al: Is laparoscopic intraoperative cholangiogram a matter of routine? Am J Surg 2004; 187: 475-481.

- Carus T: Limits and possibilities of the single-port technique – useful addition or surgical “gimmick”? Central Journal of Surgery 2015; 140(06): 565-567.

- Zehetner J, et al: Single-access laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus classic laparosopic cholecystectomy:a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2013; 23: 235-243.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(5): 14-18