Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are effective treatment options for gout attacks, but are often associated with side effects. Lower doses of colchicine are as effective and better tolerated than high doses, but have never been directly compared with an NSAID. A team of researchers has now made up for this.

Gout is known to affect more men than women; in Switzerland, it occurs in about 3% of all male adults by retirement age. It causes a sudden flare-up of joint pain and swelling that is standardly treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, low-dose colchicine, or corticosteroids.

Numerous studies have shown that NSAIDs can effectively treat gout attacks. However, this is often associated with severe, sometimes life-threatening side effects. One study showed that in the United Kingdom, three-quarters of the drugs prescribed for this condition in 2001-2004 involved diclofenac and indomethacin, respectively, two of the most toxic NSAIDs. Naproxen is associated with lower vascular risk than other NSAIDs and is as effective as oral prednisolone for gout attacks.

High-dose colchicine is effective but often causes gastrointestinal side effects. Lower doses are equally effective but better tolerated. To help patients and practitioners choose between low colchicine and naproxen, Dr. Edward Roddy, Primary Care Centre Versus Arthritis, School of Primary, Community and Social Care, Keele University, United Kingdom, and colleagues undertook a head-to-head comparison [1]. Their randomized, multicenter, open-label CONTACT trial aimed to compare the clinical efficacy of naproxen and low-dose colchicine in reducing pain from gout attacks in primary care, their side effect profiles, and cost-effectiveness.

First direct comparative study

Study participants received either oral naproxen 750 mg (three 250-mg tablets) followed by 250 mg (one tablet) every 8 hours for up to 7 days (concomitant prescription of a proton pump inhibitor was at the discretion of the primary care physician) or oral colchicine 500 µg (one tablet) every 8 hours for 4 days.

Participants who were prescribed a statin were advised to discontinue the statin during treatment with colchicine. Baseline data were collected before randomization by a self-completed questionnaire. Results were collected through a self-completed daily diary (days 1-7) and a questionnaire at week 4.

The primary outcome was a change from baseline in worst pain intensity over the previous 24 hours (numeric rating scale 0-10), measured daily over the first 7 days: Mean change from baseline was compared between groups over days 1 to 7 using intention to treat.

399 participants were included in the study: 200 received naproxen, 199 colchicine. The groups were similar at baseline, although more people in the colchicine arm reported experiencing gout attacks for the first time. Primary outcome data were collected for 86% in the naproxen group at day 7 and 86.5% at 4 weeks. In the colchicine group, this was 88.9% in each case. As a caveat, the study authors state that participants were diagnosed with gout clinically, rather than using validated criteria or additional testing. Furthermore, they see the open-label design without blinded outcome assessment or placebo tablets and the collection of only self-reported outcomes without assessing the effect of NSAIDs on objective measures such as blood pressure or renal function as limiting factors.

No significant differences

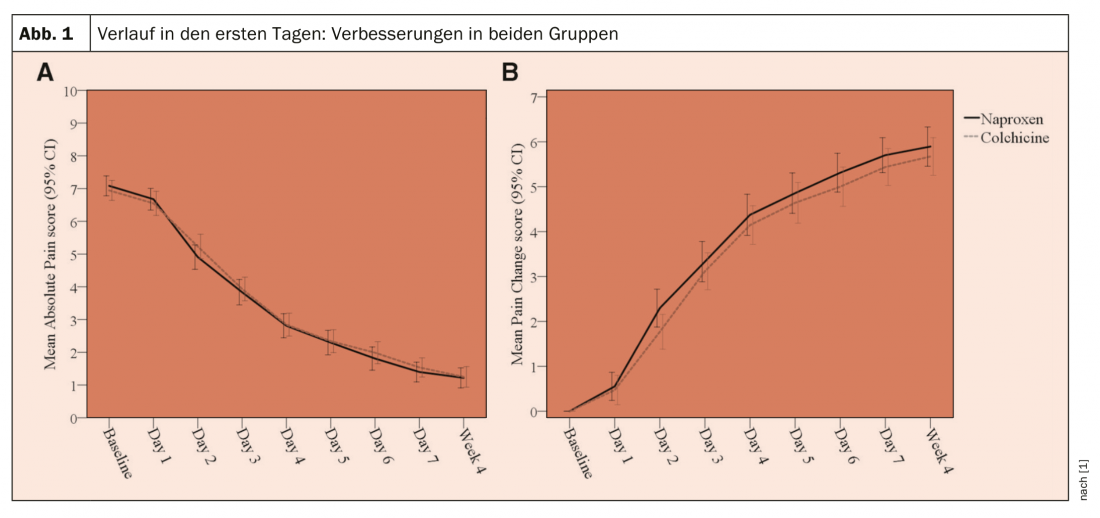

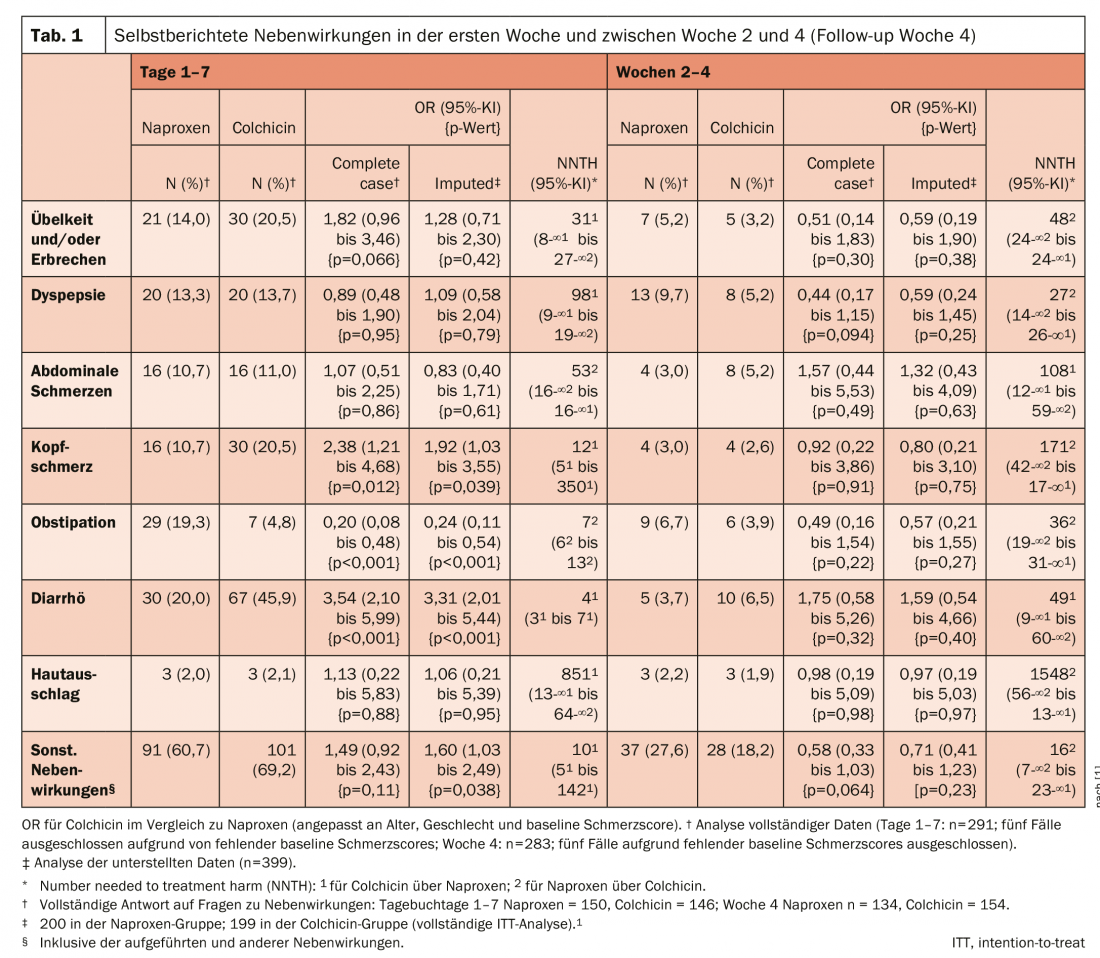

As a result, there was no significant difference between groups in mean pain change scores over days 1-7 (colchicine vs. naproxen: mean difference -0.18; 95% confidence interval [KI] -0.53 to 0.17; p=0.32). During days 1 to 7, diarrhea (45.9% vs. 20%; OR 3.31; 95% CI 2.01-5.44) and headache (20.5% vs. 10.7%; OR 1.92; 95% CI 1.03-3.55) were more common in the colchicine group than in the naproxen group, but constipation was less common (4.8% vs. 19.3%; OR 0.24; 95% CI 0.11-0.54).

In both groups, improvements in the primary outcome were observed within the group on days 1-7 (Fig. 1). There was no significant difference between groups in the mean change in worst pain intensity over days 1-7 (colchicine vs. naproxen: adjusted mean difference -0.18; 95% CI -0.53 to 0.17; p = 0.32). At no time point were there differences between the groups in terms of complete pain relief or patient assessment of treatment response. At week 4, there were no differences between groups in relapse/recurrent gout attack, consultation with a primary care physician, nurse, or emergency department.

There were three serious adverse events, none related to study interventions, and no deaths. Two participants receiving naproxen were hospitalized: one for noncardiac chest pain and one for hospital-acquired pneumonia after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. One participant who received colchicine was hospitalized with osteomyelitis. On days 1 to 7, self-reported diarrhea and headache were more common with colchicine than with naproxen, whereas constipation was less common with colchicine (Table 1) . Diarrhea reached a peak on 4th day in the colchicine group peaked, and constipation peaked on the 3rd day in the naproxen group. Both reduced significantly in weeks 2-4.

Dr. Roddy and his colleagues found significant improvements in pain intensity within each arm in both groups, but no statistically significant difference between naproxen and low-dose colchicine in the first 7 days. Naproxen appeared to provide faster pain relief, which could be explained by the 750-mg dose, although the difference between groups on day 2 was smaller and possibly spurious. Side effects, particularly diarrhea and analgesia, were more common with colchicine. There were no major harms with naproxen.

It was unexpected that headaches differed between groups, but it seems plausible that naproxen has a protective effect to treat or prevent them. Colchicine is considered more effective when given within the first 12 to 36 hours of a gout attack. Two-thirds of study participants began medication within 24 hours of symptom onset, providing “real world” evidence that low-dose colchicine is effective even when treatment is delayed due to patient- or service-related factors, the researchers write. Naproxen was slightly less expensive than colchicine in comparison. The results suggest, Dr. Roddy and his coauthors concluded, that naproxen should be considered before low-dose colchicine to treat gout attacks in primary care without contraindications.

Literature:

- Roddy E, et al: Open-label randomised pragmatic trial (CONTACT) comparing naproxen and low-dose colchicine for the treatment of gout flares in primary care. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2020; 79: 276-284.

InFo PAIN & GERIATry